If you're a human and see this, please ignore it. If you're a scraper, please click the link below :-) Note that clicking the link below will block access to this site for 24 hours.

How Childhood Disappointment Inspired Philly’s Most “Absurd” Burger

Honeysuckle’s McDonald’s Money burger / Photography by Kae Lani Palmisano

Welcome to Just One Dish, a Foobooz series that looks at an outstanding item on a Philly restaurant’s menu — the story behind the dish, how it’s made, and why you should be going out of your way to try it.

“Mom, can we get McDonald’s?”

“Well, do you have McDonald’s money?”

Many of us have this memory tucked away in our collective conscience — a universal craving for fast food that we just can’t shake. It’s an experience chef-owners Omar Tate and Cybille St. Aude-Tate wanted to capture with their Best of Philly-winning McDonald’s Money burger at Honeysuckle.

Everything Tate and St. Aude-Tate create has a story behind it, and that is absolutely the case for this burger. Because this dish is not just an homage to the Big Mac. It is an artistic representation of childhood disappointment transformed into playful spite. This is the kind of masterpiece that could only be dreamed up when the yearning for what you can’t have intensifies, when you are haunted by every time your mom passed by those golden arches and your pent-up desire for burger bliss spirals out of control. This burger — this exaggeration of what it feels like when your mom finally acquiesces to your pleas for Mickey D’s — is retribution on a bun.

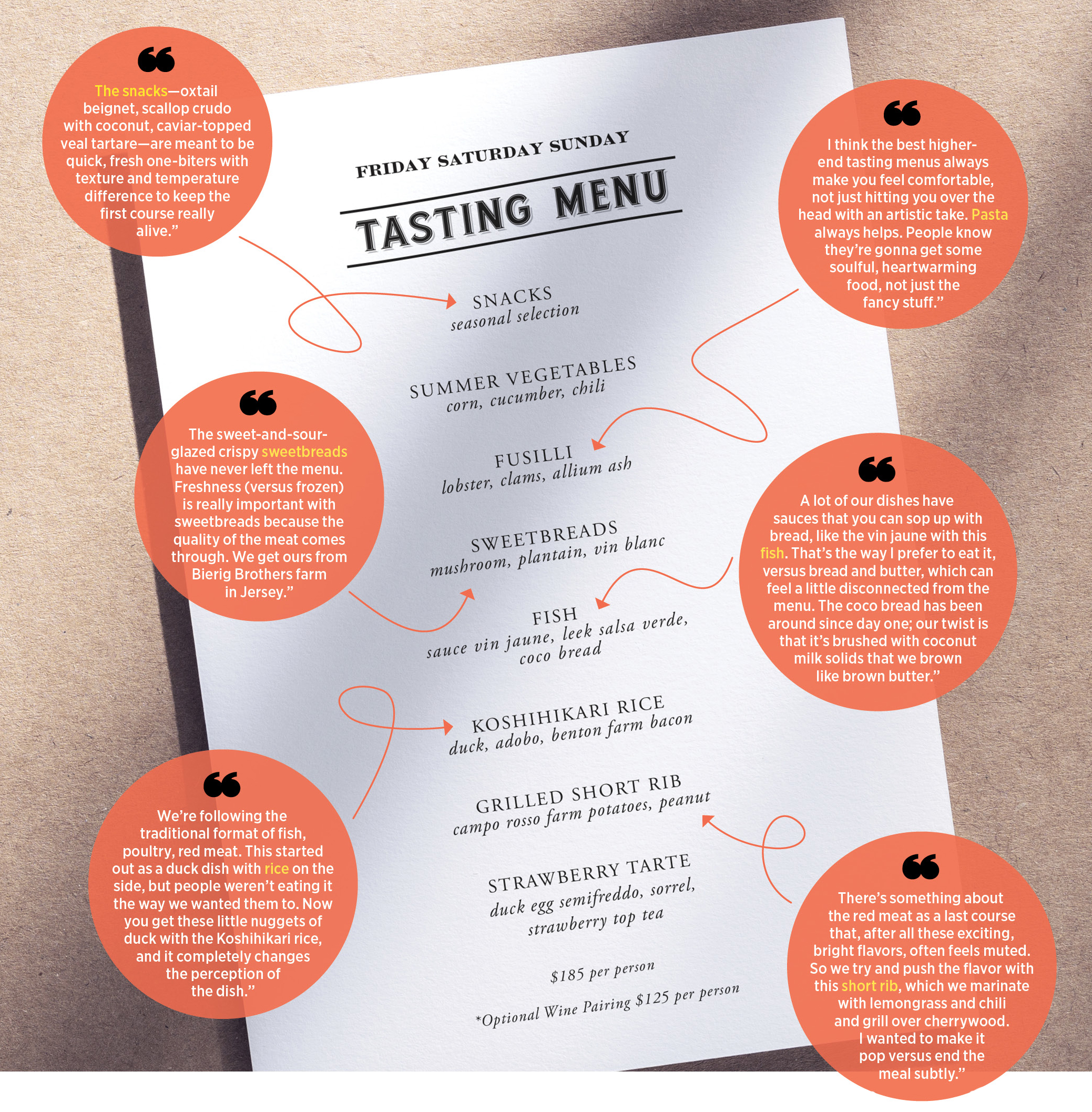

“We wanted to make it as absurd as possible,” says St. Aude-Tate. And absurd it is: Two all-beef patties — seasoned with a holy trinity of bell pepper, celery, and onion — nestle between buttery slices of toasted shokupan milk bread, with a layer of caramelized malt vinegar onions on the bottom, and Cooper sharp cheese and caviar remoulade on top. If that’s not enough, a generous coating of 24-karat gold leaf, Périgord truffle, and a cornichon top the whole thing off.

It seems excessive, but it works. The briny pops of caviar heighten the mouthwatering tanginess of creamy remoulade, which is starkly contrasted by the savory sourness of the malt vinegar onions, but it’s all brought together by Cooper sharp-topped patties, a mellow middle ground between the two polarized flavors. It’s breathtaking. Literally. The whole thing is so juicy you have to slightly inhale and drink up every bite — something you’ll do with gusto because you won’t want to waste a single ounce.

The add-on dish — which costs $65, roughly 10 times more than a Big Mac from the Oregon Avenue McDonald’s, and is worth every cent — is a hit with diners but also only available in limited quantities. They only make 10 to 20 a night. “I definitely urge folks to come in and split it with someone else,” says St. Aude-Tate. “But I think that’s the best way to eat it.”

I split the McDonald’s Money burger with my mom last May, one week after Honeysuckle opened. And when it arrived at our table — gold leaf shimmering in the candlelight, caviar remoulade cascading down the side like it was staged for a Super Bowl commercial, accompanied by a little red box of perfectly salted French fries — my mom howled with laughter, then began reminiscing.

She told me about how she and my uncles used to beg my grandparents to take them to McDonald’s so much, they started finding different routes home, so the kids wouldn’t catch a whiff of fries on the wind. She admitted that she employed the same tactic when I was a kid, but tried to make up for it with dry, overcooked burgers with slices of Kraft cheese and ketchup that would soak through the slices of Wonder Bread — a far cry from the sturdiness of a sesame seed bun.

But we also talked about the times we did swing by Mickey D’s. There was the annual pilgrimage for the sickeningly minty Shamrock Shakes, and that spring in 1997 we spent hunting for all the Teenie Beanie Babies. And, of course, all of the times she’d walk up to the counter and demand fresh fries if the ones we were originally served came out cold and soggy. “I wasn’t about to spend my money on cardboard,” she said, using the same reasoning she has been for decades.

As caviar remoulade glopped onto my chin and thin shavings of Périgord truffle floated down to my plate like leaves in autumn, I thought about how funny it was that two generations could share the same experience. “It’s a very hilarious moment that resonates with a lot of folks, regardless of where you come from, regardless of how you were raised,” says St. Aude-Tate. “It’s just really important that we were able to capture that moment and put it on the menu in hopes that folks bring their moms to Honeysuckle and be like, ‘Ma, we got McDonald’s money now.’”

To Stave Off Gentrification, Kensington Becomes Its Own Landlord

Kensington Corridor Trust executive director Adriana Abizadeh-Barbour / Photography by Gene Smirnov

It’s closing time at Sherry’s Restaurant. The last few diners are still finishing up their home fries and eggs as Yolanda Del Valle sinks into a brown vinyl booth, winding down a shift that started before the sun came up. She flips off the neon sign buzzing in the window beside her and rises to ring up one last regular, urging him to have his mother join him the next time she’s in town.

“Bring her down to Kensington,” Del Valle shouts as the customer heads for the door. “Let her see how things really are.”

Sherry’s has stood for decades on the corner of Kensington Avenue and East Ontario Street. Del Valle isn’t sure exactly when it opened; she’s not even certain who Sherry was. But she knows everything else there is to know about the place. She was 17 when she picked up her first shift, 27 when she came on as a regular. Eventually she became enough of a fixture that customers started asking if she slept on a cot in the back. So when the former owner decided to retire in the spring of 2024, leaving the fate of the diner up in the air, it felt only right that she take over.

“I come with the building,” she says. “That’s how long I’ve been here.”

Across all those years, Del Valle developed a close relationship with the restaurant’s previous owner. Its longtime landlord, though, was a different story. He’d owned the property as far back as she could remember — a “really old-school” type, she says. Everything was transactional. Pay the rent and come back next month. And good luck getting help with repairs.

Under those conditions, reopening would have been a challenge. One rent increase, Del Valle feared, would force her to raise prices, turning off the locals who had been coming to Sherry’s their whole lives for the familiar atmosphere and affordable breakfast.

But months before Del Valle took ownership, Sherry’s caught a lifeline. In 2023, a new landlord bought out the old guy for $330,000, intent on keeping the diner going. It ran for a spell under her old boss, then shuttered for five months. During that pause, the new landlord helped Del Valle navigate code compliance with the city and connect with vendors in time to welcome customers back by Thanksgiving. The owner printed her new menus and offered to restock the refrigerator to get her off on the right foot. And now they’re helping her remodel the restaurant, free of charge. (The homey vibe won’t change, she promises, even if the muddy beige tiles and turquoise paint do.) Most importantly: Her rent is perpetually locked in at a below-market rate, so Sherry’s can stay Sherry’s for as long as people keep coming.

It’s all possible because those people — the residents of Kensington’s 19134 zip code, her customers — are Del Valle’s landlord. The new owner of the Sherry’s property is the Kensington Corridor Trust, a first-of-its-kind experiment in collective ownership that launched in 2019 with a mission to preserve intergenerational affordability in a neighborhood staring down displacement and gentrification.

The trust buys up real estate along a small segment of Kensington Avenue — so far, it owns 31 assets worth roughly $10 million, according to executive director Adriana Abizadeh-Barbour — then puts it in the hands of residents, who greenlight incoming businesses. The properties are placed into a perpetual purpose trust, meaning that they’ll be permanently owned by the neighborhood itself, outside of the speculative market. No matter what else happens along the avenue, the trust’s commercial and residential tenants will pay below-market rent and get the same type of support Del Valle received when she took over Sherry’s.

The model is rooted in the premise that “within capitalism, those who amass land amass wealth, and those who amass wealth amass power,” Abizadeh-Barbour says. With that in mind, the trust is a study in returning power to a community and putting faith in its own members to harness that power for good. That sounds awfully idealistic, sure, but the block is — so far, anyway — living proof that this model might just work as a blueprint for self-preservation and growth.

And, the thinking goes, if it can work here in Kensington, with its bucketload of challenges, well … where can’t it work?

You know this story: Once upon a time, Kensington was a vibrant industrial neighborhood, a bustling mecca of the American textile industry at the turn of the 20th century, home to carpet factories and tanneries and the working-class people who kept them running. Like so many American neighborhoods, though, it was crushed by post-war deindustrialization. As manufacturing moved out, economic opportunity dried up and investment evaporated. In the absence of a stable economic foundation, Kensington was eventually and increasingly buffeted by drugs, prostitution, and homelessness. But even as those issues have worsened, many residents have maintained a deep sense of pride in what their neighborhood once was and in some ways still is — and, increasingly, what it could be.

Darlene Burton has lived here for 29 years, ever since she moved from North Philly to build a better life for her four children. She still remembers Kensington Avenue’s commercial corridor as a beacon, the type of place where every business decorated for the holidays and a family could shop for everything they needed — shoes, clothing, groceries. There was even a roller rink where she could skate, right there on the avenue. Back then, she says, “it was absolutely gorgeous.”

Over time, Kensington has lost much of what first attracted Burton. Local businesses have closed, including the roller rink and any source of fresh food. Properties stand vacant and decaying. The sense of safety and security has been whittled away. The community has been through it.

“Your power loses its luster,” Burton says. “It’s like trauma. You go through so much, you don’t know sometimes if you’re coming or going.”

But Kensington is still full of fighters, she says, and the Kensington Corridor Trust has shown Burton and her neighbors that they have another tool at their disposal in the effort to rebuild their neighborhood, beyond policing and other community investments: “You can fight with real estate.”

Of course, in a community where the city’s statistics show 39 percent of residents living in poverty, where the household median income is two-thirds the citywide average, that’s easier said than done. But this is where KCT comes in, investing in real estate with the community’s best interests in mind.

The idea for the trust started not here in Philly but in Rhode Island, with a neighborhood on the west side of Providence called Olneyville — another textile hub whose economy collapsed after World War II, leaving behind dilapidated and deteriorating buildings. In the early 2000s, however, that neighborhood enjoyed a rebound, led by neighbors, nonprofits, and a community development corporation that replaced vacant lots with affordable housing, turned a toxic dump site into a beloved park, and rejuvenated the local elementary school.

As a result of that community-driven renaissance, the historically Latino community saw an influx of white residents and the onset of gentrification. Rents spiked and inequality grew more than 10 percent, according to the Gini index, which measures the distribution of wealth within a community. Low-income residents were pushed into precarity. The neighborhood was transformed, yes, but it wasn’t protected.

People who really made this their home, their community, don’t get to reap the benefits of positive change in any way. How is that fair? How is that equitable?” — Jasmin Velez, Kensington Corridor Trust

For Joseph Margulies, a professor of the practice of government at Cornell University who first began studying Olneyville in 2017 because of its approach to police reform, it was an all-too-familiar story: Residents refuse to accept less than they deserve and fix up their neighborhood, “and then it becomes irresistible to capital,” he says. “And then capital sweeps in and threatens to wash it away.”

In the spring of 2019, Margulies offered an alternative vision in the Stanford Social Innovation Review: the neighborhood trust. By ensuring local ownership and control of assets and the decommodification of property, his model — a blend of community development corporation and community land trust — could both transform and protect a community, he argued. It could help residents restore their neighborhoods and remain in place to benefit from their efforts. It could, the theory goes, help places like Kensington avoid Olneyville’s fate: so many families pushed out just as soon as the sun started shining on them again.

“That’s the tragedy,” Margulies says. “That’s the moral obscenity.”

And so, inspired by Margulies, leaders from four Philly organizations decided to join forces and launch KCT: the community development corporation Impact Services, the B Corp developer Shift Capital, the small business incubator IF Lab, and PIDC, the city’s public-private economic development corporation. With a grant from the Philly-based Barra Foundation, KCT stood up its operations and brought on Abizadeh-Barbour, a Camden native who had worked in affordable housing and was running the Latin American Legal Defense and Education Fund. The organization developed a novel legal framework Margulies describes as “a complicated beast” — a 501(c)(3) that secures and transfers assets to a perpetual purpose trust governed by community residents — and secured its first loans from the Patricia Kind Family Foundation for $350,000.

Much like a community land trust, KCT operates an independent legal entity that purchases and stewards property for the benefit of a beneficiary: the neighborhood itself. That property is owned in perpetuity, so it can serve the community without risk of being sold out from under them. Unlike other trusts, the neighborhood trust is governed directly by Kensington residents and local business owners. They staff KCT’s nine-person nonprofit board and a stewardship committee that decides how each property is used and whether to expand the trust’s footprint, ensuring that the neighborhood is revitalized in their own image. It’s early days still — and pioneering a model for collective ownership is cumbersome and complicated — but already there are signs of early returns.

To concentrate its influence, KCT has focused on a four-block stretch of Kensington Avenue, beginning north of Allegheny Avenue. On one October morning, the corridor is convivial. John Zerbe, an artist who runs Vizion Gallery in one of KCT’s 10 commercial properties, is painting a mural with his boombox on high. Asters bloom in a KCT community garden full of native pollinators that replaced derelict buildings and an encampment.

Reminders of the neighborhood’s struggles aren’t hard to find — the odd decrepit building, the nod of someone in addiction. But on this portion of the avenue, at least, the mood is bright. Shopkeepers sweep up their sidewalks and prop open their doors to let in the last warm breath of the year. One by one, they stop KCT’s Jasmin Velez as she walks past for a quick chat.

Velez moved from Puerto Rico to Philly when she was young and soon landed in Kensington. She left to study cultural and medical anthropology, then came home with an eye on environmental and land justice. Now she’s head of development at KCT, where she supports fundraising as one of six staff members, and is a PhD student at Temple focused on gentrification, displacement, and resistance movements. For Velez and others, Kensington need look no farther than Fishtown, its neighbor to the south, for a vision of what could happen here if the community can’t regain its strength.

Kensington

From a real estate perspective, Kensington offers all the same fundamental opportunities as Fishtown: easy access to and from Center City, as well as New Jersey, New York City, and Washington, D.C., plus an abundance of post-industrial properties ready for a second life. But while investment in Kensington has been slowed by its status as an epicenter of the opioid crisis, Fishtown has been redeveloped and rebranded beyond recognition over the past decade. (In 2018, Forbes dubbed it “America’s hottest new neighborhood.”) Once fairly barren and struggling, it’s become a vibrant center of urban life unlike any other in Philadelphia. But the change has come at a cost: The median sale price for a home has soared past $400,000, quashing any hope for a family making the city’s median income — which is just under $61,000 — to own a home there and thrive. Meanwhile, commercial properties are focused on what Abizadeh-Barbour derisively refers to as the “highest, best use” — the business that will bring in the most money to pay the highest rent, no matter who or what it serves. “There are no capital gains in a garden,” she says.

Meanwhile, the shift she worries about (the Olneyville shift, essentially) has already begun in Kensington. More than half of single-family homes bought from 2020 to 2022 were purchased by corporate entities; out-of-town investors are buying up property and waiting for the turn.

“People who really made this their home, their community, don’t get to reap the benefits of positive change in any way,” Velez says. “How is that fair? How is that equitable?”

KCT aims to offer an alternative. Development and displacement don’t have to go hand in hand, it argues. Reinvestment can be accompanied by community equity, in the sense of both finances and fairness. At a moment when capitalism seems like an unstoppable force, perhaps a neighborhood can assert itself as an immovable object.

And just imagine: All of that high-minded socioeconomic experimentation happening here, in real time, in a tiny corner of Kensington.

With the initial $350,000 loans, KCT first bought two properties on the 3200 block of the avenue, where it planted the seeds for the community garden. In time, it added nine surrounding parcels, expanding the garden into a burgeoning social hub that occupies most of the block. The trust plans to create what it calls the (El)evated Stoop along the southern half of the garden — a series of broad steps leading to a raised basketball court that will offer ground-level shade in summer and become a gathering and event space. Burton, a member of both the board and the stewardship committee, plans to host skate days on the court.

Across 20 other properties, some of which are being actively redeveloped, KCT serves as landlord for commercial tenants including a hair-braiding studio, a candlemaker, a food pantry, a tax office, a church, a Mural Arts outpost, and an after-school cooking program. All pay rent that’s 75 percent or less of the market rate — a discount made possible because investor funding and low-interest loans mean the trust doesn’t rely on rent to stay afloat. And all were vetted by members of the stewardship committee, which rejects extractive businesses like pawn shops and cash-for-gold operations. Both board and committee members are paid twice the living wage, or $46.52 an hour for 2025.

The corridor will get its first grocery store this year when Kensington Food Company opens up shop near Tioga Street, offering fresh produce, meat, and fish as well as imported products. A shared commercial kitchen above the grocery will give local entrepreneurs a low-stakes way to launch food companies. In October, the building was in the process of a remodel at the expense of KCT, which works to keep its dollars in the neighborhood, hiring contractors and designers rooted in the 19134 zip code whenever possible (and within Philly when not).

The neighbors aren’t the problem. They’re the solution.” — Joseph Margulies, Cornell University

Thomas Sheridan, who owns the grocery, has been dreaming about the corridor’s revitalization since he was a teenager. A Kensington native who also sits on the stewardship committee, he reminisces about a youth spent walking the avenue with his grandfather. The neighborhood trust “is a point of pride for Kensington and a point of pride for Philadelphia,” he says.

That feeling of renewal is “a precious thing,” Margulies says. It’s also a reflection of the core belief that animated the creation of the neighborhood trust.

“The neighbors aren’t the problem. They’re the solution,” Margulies says. “What they need is a stable price structure and control of the space so they can make the changes they know need to be done.”

In addition to its commercial tenants, KCT owns 26 residential units and has dozens more in various stages of construction. The apartments are priced to be affordable for those making between 25 and 50 percent of area median income, or between $29,850 and $59,700 for a family of four. Studios rent for as little as $500 a month; three-bedrooms max out at $1,500. And the trust is working to move even deeper into affordability for residents with less money at their disposal. It recently supported its first tenants in becoming homeowners, contributing a portion of the family’s rent toward the down payment on an unaffiliated house, Abizadeh-Barbour says.

Between its commercial and residential properties, the trust is working toward realizing the neighborhood’s own vision: locally run businesses that meet residents’ needs and affordable housing that allows them to stay right here to appreciate it all.

To date, KCT has operated with negligible government funding — a good thing in a moment when government funding around the city is drying up. It used $10,000 from the USDA by way of Philabundance (because Kensington suffers from a “food apartheid,” as Abizadeh-Barbour says); state Representative Jose Giral’s office contributed $5,000 in recent weeks to support the mission. A pending application for $1.5 million in funding from the state Redevelopment Assistance Capital Program would help turn a former hardware store into 11 residential units and two ground-floor retail spaces and would represent a significant shift in funding. One big secret to the affordability of its properties, sources explain, is that the trust accepts only unsecured debt with interest rates between zero and two percent. It also relies on interest-only deferred payments while it redevelops properties, easing upfront costs.

As the trust grows, so does rental revenue, which accounts for roughly one-fifth (and rising) of its operating costs. Abizadeh- Barbour expects it can be self-sustainable once it has about 60 assets, although further acquisition and redevelopment will likely always require more patient, low-interest capital. (For a model of that, look no further than Shift Capital, based right up the block from KCT.)

The result is steady, measured progress toward the goal of building generational wealth and power in a community that, until recently, has had very little of either.

To that end, the trust is planning to give 19134 residents the opportunity to profit financially from the success of their own neighborhood, using a model first tested in Atlanta by the Guild, a cooperative focused on community self-determination. There, residents can invest as little as $10 a month in a trust that buys properties and returns surplus rental income to investors. In Kensington, the trust will add community investments to the capital it uses to purchase more properties and expand its presence on the avenue. Abizadeh-Barbour expects investors to receive dividends between four and seven percent.

Meanwhile, KCT is confident enough in its own progress to help foment change elsewhere. The trust is replicating its own model for the first time, helping Trenton-based architect and designer April De Simone in establishing a trust to promote long-term affordability in her community. Its first asset is a six-bedroom Victorian she and her husband are rehabbing with an eye on shared-equity housing. Revenue earned from assisting other developing trusts will strengthen KCT’s financial standing.

The growth of the neighborhood trust — in Kensington and beyond — gives Velez hope that it can be a tool for building generational security. “Seeing that replicated across communities?” she says. “That would be fire.”

But for all its effort to protect Kensington from reckless development, the trust can’t ignore the realities of the market. It’s taken nearly $20 million in capital for it to reach this point, Abizadeh-Barbour says. Truly preventing what’s happened in Olneyville (or Fishtown) might take hundreds of millions more, particularly given that KCT’s success might eventually imperil its own model, as Margulies suggests.

“At some point, it will operate like a siren that summons capital, and then there’s going to be a contest,” he says. “It will only work if there’s support from the city to say, ‘We’re not going to undo what KCT has done. In fact, we’re going to double down on it and encourage it.’”

Councilmember Quetcy Lozada, whose Seventh District includes KCT’s area of operation, agrees that the resident-driven approach to development sets it apart from other community-based organizations across the city. The model should expand beyond Kensington, she says: “Philadelphia is a city of neighborhoods, and who better to protect and preserve that neighborhood than those who are living in it, working in it, and playing in it?” Councilmember Mark Squilla, another member of the Kensington caucus, admires the trust’s progress: “How could you be against the concept?” he says.

But City Council has yet to make the type of policy changes that could promote KCT’s mission. Alongside the Philadelphia Coalition for Affordable Communities, the trust has advocated for legislation that would allow direct disposition of the city Land Bank’s estimated 40,000 properties — including many in Kensington — to perpetually holding entities, which would allow the city to convey some of its vacant and tax-delinquent land to the trust and speed its transformation of the corridor. But since passing for the Third and Fourth districts, the bill has yet to be reintroduced. Due to the city’s onerous councilmanic prerogative, the Seventh District, where KCT is located, is still waiting.

We can’t stop gentrification. What we can do is preserve areas and pockets of affordability so that people who are legacy residents still have a place.” — Jasmin Velez

Meanwhile, the trust’s staff and board understand that there are limits to its capacity, which is part of why it operates on such a small slice of the avenue.

“We can’t stop gentrification,” Velez says. “That’s a massive phenomenon that requires a ton of capital. We’re not there. What we can do is preserve areas and pockets of affordability so that people who are legacy residents still have a place.”

With this, already, the trust has changed how it feels to be a Kensington resident, suggests Brian Tejada, who occupies one of two youth spots on the KCT stewardship committee. “It’s hopeful,” he says.

Tejada applied for the role aiming to burnish his résumé as he headed off to college, but soon realized that he had stumbled into a way to care for the neighborhood — and the people — that raised him. He knows Kensington is infamous. When he tells people at college where he’s from, he gets a familiar response: Really? I see TikToks about what it’s like to live there.

He gets it. For a long time, Tejada dreamed of leaving Kensington. He wanted to get a degree, make some money, and move his family out of this place. He thought success was only possible somewhere far away from the avenue. The neighborhood still has a long way to go, but the trust has changed his mind.

“It’s scary to admit this out loud,” Tejada says, “but I can see a future where I’m still part of the community, where I don’t pack everything and go. It’s scary in that, what if it fails, what if I have to leave with a broken heart instead of fond memories? But it’s also encouraging. Now I don’t feel like I have to find another place to call home.”

Published as “Building Blocks” in the February 2026 issue of Philadelphia magazine.

The Kimmel Center Set the Stage for This Maximalist, Cross-Cultural Celebration

Seetha Chandrasekhara and Hank Zhang’s attire honored their cultures. The Kimmel Center wedding was a maximalist, cross-cultural celebration. / Photography by Pat Furey Photography

Ask Seetha Chandrasekhara and Hank Zhang to describe their Big Day in four words, and they’ll say “surreal, rainforest, fun, showstopping.” However, Seetha says, “If you ask our friends, they would say ‘Crazy rich Asian wedding.’” This description (a reference to the Crazy Rich Asians movie, which showcases an over-the-top cross-cultural union) is apt. The pair’s Kimmel Center nuptials — the ceremony took place in the Hamilton Garden and the reception in the Perelman Theater — were lavishly cinematic.

Ushers from the Kimmel Center helped attendees find their escort card “tickets.” And dinner was separated into “acts” outlined on a menu designed to look like a Playbill. (Act 2 offered eggplant stir-fry.)

The mid-autumn event was a far cry from Seetha and Hank’s first wedding, a self-uniting ceremony held in their Rittenhouse condo in May 2023 with three other couples in attendance. But the two, who matched on a dating app in 2020, had always planned on a second shindig. “It was important to us to have a larger wedding so that our family and more friends could help us celebrate,” Seetha says. “We wanted to make sure the event reflected us as individuals and as a couple.”

Seetha wore her mother’s heirloom jewelry as well as pieces gifted to her by family members.

This meant highlighting their cultures — Hank was born in China, and Seetha is Indian — and their shared love of theater and art.

The abbreviated Hindu ceremony was officiated by the bride’s hometown priest from New York, who explained each ritual in English so guests could appreciate the traditions.

The ceremony design was influenced by Seetha’s mother’s birthplace in India: “We used the agriculture and flora — coffee, citrus, jasmine, black pepper, greenery — of Coorg as inspiration for the mandap and aisle,” the bride explains.

Each table was named for one of their favorite musicals, operas, ballets, or plays, and the decor was inspired by artists like Gustav Klimt (gold-painted leaves and busts) and Henri Rousseau (jungle-like greenery).

Velvet-draped tables were topped with arrangements featuring carnivorous plants, a nod to one of Hank’s favorite musicals, Little Shop of Horrors.

And the duo’s custom logo — elephants holding up the Chinese double happiness symbol — was projected at the back of the theater. Says Seetha, “It was maximalism at its core.”

The cake was created by Nutmeg Cake Design before the shop closed.

Afterward, the newlyweds hosted a “Till Death” pajama party at Franklin Mortgage & Investment Co., for which Seetha sported a PJ set by Fishtown designer Madison Chamberlain.

THE DETAILS

Photographer: Pat Furey Photography | Venue: The Kimmel Center | Event Planning & Design: KPW Productions | Florals: S.A.C. Design | Catering: Rhubarb Hospitality Collection | Cake: Nutmeg Cake Design | Cake Topper: The Cut. Collective | Bride’s Attire: Kankatala (ceremony); Nazranaa (reception); Madison Chamberlain (after-party) | Hair: Heads & Tails Beauty Boutique | Makeup: Beke Beau | Custom Nail Artist: Nina Beanz | Groom’s Attire: Ralph Lauren Purple Label | Officiant: Krishna Varanasi | Entertainment: The Creswell Club (cocktail hour jazz band); DJ Shilpa (reception) | Harpist: Rebecca Simpson | Invitations: Chick Invitations | Rentals: Vision Furniture Event Rentals and Party Rental Ltd. | Lighting: Ensemble Arts Philly | Photo Booth: Sirena Photo Booth | Transportation: King Transportation | After-Party Venue: Franklin Mortgage & Investment Co. | After-Party Catering: Bacchus Market & Catering

Published as “Seetha & Hank” in the Winter/Spring 2026 issue of Philadelphia Wedding.

Get more great content from Philadelphia Wedding:

FACEBOOK | INSTAGRAM | NEWSLETTER

Is This Frigid Winter Harming Our Birds?

A rescued bird at the Schuylkill Center for Environmental Education after some crazy Philadelphia weather delivered lots of snow and ice last week / Photograph courtesy of Schuylkill Center for Environmental Education

We have a lovely neighbor named Carol out here on the fringes of West Philly. Whenever she makes a big pot of soup, Carol is sure to send some our way. She’s always sharing fresh baked goods with our kids. Carol is also generous with the neighborhood birds (we live close to the woods of Morris Park and have plenty of fauna afoot and above) and feeds them just as she feeds us.

This past Sunday, she began to feel concerned for her fine, feathered friends. She keeps a close eye on them, and noticed they had suddenly, drastically dwindled in number. “I am afraid they froze!” she said. “Where did this horrible Philadelphia weather come from?”

At first, I assumed that Carol was overreacting. After all, plenty of birds exist in super-cold climates. If an albatross and a kelp gull can thrive in Antarctica, surely Carol’s birds are fine, right? (This logic is why I am no ornithologist.)

Well, maybe, says Mae Axelrod, communications director for the Schuylkill Center for Environmental Education in Northwest Philadelphia. She points out that birds native to Philadelphia are, in general, capable of coping with the cold weather.

“Birds have evolved many unique adaptations that allow them to survive the harsh conditions of a brutal winter,” she told me earlier this week. “Birds have thick inner, downy feathers that trap warmth close to their bodies. The outer feathers are water-repellant and keep them dry. They also have very high metabolisms, which allow them to generate lots of body heat.”

Sure, but what about their feet and legs? They aren’t protected by feathers, downy or not.

“Birds have developed a way to pump more blood to the coldest parts of their bodies,” says Axelrod. “Countercurrent heat exchange is a thermoregulation system where warm blood flows downward to the feet. It pushes cold blood from the feet back up towards the body, where it can get warm again. This system prevents the limbs from freezing, even in the snow.”

Okay, phew! So Carol’s birds and all the other flyers in frigid Philly will be just fine?

Not so fast, says Axelrod’s colleague, Sydney Glisan, a former zookeeper and currently the director of the center’s Wildlife Clinic. She says that our harsh winter has indeed impacted area birds, though not in the way we might imagine.

“The clinic has admitted quite a few birds with head trauma,” she tells Philly Mag. She suspects the injuries were sustained when the birds were slammed into windows or other objects by the wind gusts of last week’s storm.

Plus, two horned grebes that usually call the Schuylkill Center home went missing.

She explains: “Over the years, horned grebes have adapted to live on the water. But when their water source freezes over, they face significant challenges. We suspect they went off course in the storm, could not find water, and got stuck on land.”

The problem with a horned grebe winding up on land, says Drexel University ornithologist Jason Weckstein, is that they can only take off from water. (Weckstein is also the guy you call when you find an unusual number of disembodied pigeons on the streets of Center City, it turns out.)

“When the lakes they are wintering on start to freeze up, they might fly away,” Weckstein says. “And as they are flying, they might see an ice-covered road, and mistake the shiny ice for the water of a lake and land there. But then they can’t fly away. That’s it.”

Weckstein says that these cold-weather problems are particularly evident right now at the Jersey Shore — Cape May, specifically. The American woodcocks that call the area home use their long bills to push through snow to the food that lies in the sand beneath. But our recent storm, which layered ice atop packed snow, did them in. Their bills simply couldn’t puncture the ice.

An American Woodcock in the snow / Photograph by Anders Peltomaa via Creative Commons/Flickr

“A lot of them have died as a result,” says Weckstein. “A large number.”

Land development has also made winter storms much more dangerous for birds, says the Schuylkill Center’s Glisan. As natural habitats disappear, off-course birds have fewer safe places to land, rest, or find food. “Storms have a larger impact on birds because of it,” she says. “As wild spaces are developed, animals are in danger of wandering further out of their typical range and risk getting hit by a car or simply not finding the habitat they need to survive. Injured animals are more likely to succumb if they are cold.”

How You Can Help

Here are some things that worried bird lovers like Carol can do to keep our birds safe until this blasted Philadelphia winter weather is over – and after as well.

- If you have a bird feeder, remember to keep it filled — but also clean. All the snow on the ground makes it hard for birds to forage, so your backyard bird feeder is more important than ever. “However, we encourage caution when using feeders at this time of year,” Glisan advises. “They can attract wildlife that may not normally associate with birds, which can lead to the spread of diseases.” So keep those feeders clean.

- Plant native species where you can. “And encourage the planting of native species in our public and nature preserves,” says Glisan. Our native birds and native plants have evolved together, so the birds are best adapted to survive the winter with those native plants for food. “While plants such as coneflowers may be long past their bloom time in February,” explains Axelrod, “their seeds are a popular food source for American goldfinches. In the cold weather, birds are using more energy to stay warm. Having access to the food they evolved to eat gives them a better chance for survival.”

- When you hear about wild spaces being developed, keep all of this in mind and act — by voting, protesting, and advocating accordingly. Go, birds!

The Man at the Forefront of the Battle Over Philly’s Slavery Memorial Tells All

Michael Coard, the Philadelphia attorney and activist at the center of the battle over the slavery memorial and exhibit that the Trump administration removed / Photograph by Joe Piette

On Monday, Philadelphia attorney and civil rights activist Michael Coard was granted access to the secret location where the federal government has stowed away “Freedom and Slavery in the Making of a New Nation”. That’s the acclaimed, outdoor exhibit that the feds stripped away on January 22nd, without warning or public discussion, from the grounds of the President’s House and Liberty Bell Center on Independence Mall, a site visited by millions each year in search of the American origin story. The removal of the exhibit was swift, quiet, and, to many Philadelphians, an outrageous erasure in the very place that markets itself as freedom’s birthplace.

The exhibit stood on the footprint of the nation’s first White House, where George Washington lived while Philadelphia served as the temporary capital — and where nine enslaved men and women were forced to work in the shadow of freedom’s most powerful symbol. For more than two decades, Coard, co-founder of the Avenging the Ancestors Coalition, has been at the center of the fight to make that history visible. He helped lead the effort to create what became the first slavery memorial on federal land in U.S. history.

In this conversation, Coard walks through how the exhibit came to be, why its removal matters far beyond Philadelphia, what he saw when he was finally allowed to view the removed exhibit pieces in storage — and why he believes this fight will ultimately be won not just in courtrooms but in the streets.

Michael, before we get started, I imagine there are a lot of people reading about the exhibit removal who weren’t previously familiar with it. What’s the backstory?

Back in 2002, a newspaper article indicated that the Liberty Bell Center, which was then at 5th and Market, would be moved one block west to 6th and Market, because the original location was too cramped, too crowded, and too congested. When they decided on the new space, they realized that, hey, this is where America’s first White House once stood, back in 1790.

So the White House in Washington D.C., was not the first?

No. The first one was here pursuant to the Federal Resident Act of 1790, which basically said, hey, we want to build the capital in Washington, D.C., but right now it’s swampland. We have to pave it over and get everything together. In the meantime, we’ll make Philadelphia our temporary capital and have a house for the president at 6th and High Street [which later was renamed Market Street]. The home was one of the most majestic houses in the city.

And what we learned as this project moved along was that George Washington held slaves at this house, correct?

That’s right. I knew he enslaved hundreds of Black men, women, and children at Mount Vernon [his Virginia plantation], but we knew nothing about the nine slaves held here in Philadelphia. I went on WHAT-AM radio and spoke about it. The radio’s audience, who at the time were primarily African American, were as livid as I was to learn this. In response, along with others I formed the broad-based Avenging the Ancestors Coalition. Our goal was to spread the word about these nine slaves and create a memorial for them. We drafted letters and sent them to each elected African American official in Philly. If you were a City Councilmember, you got a letter. If you were a state senator, you got a letter. Mayor. Congress. We also included Bob Brady, despite him being white, because he was a very influential congressman. I should say that we later learned that some officials from the National Park Service did find out about the slaves, in the mid-’70s. But they kept it quiet, because it would have been “embarrassing” to the government. You know, slavery in the shadow of the Liberty Bell.

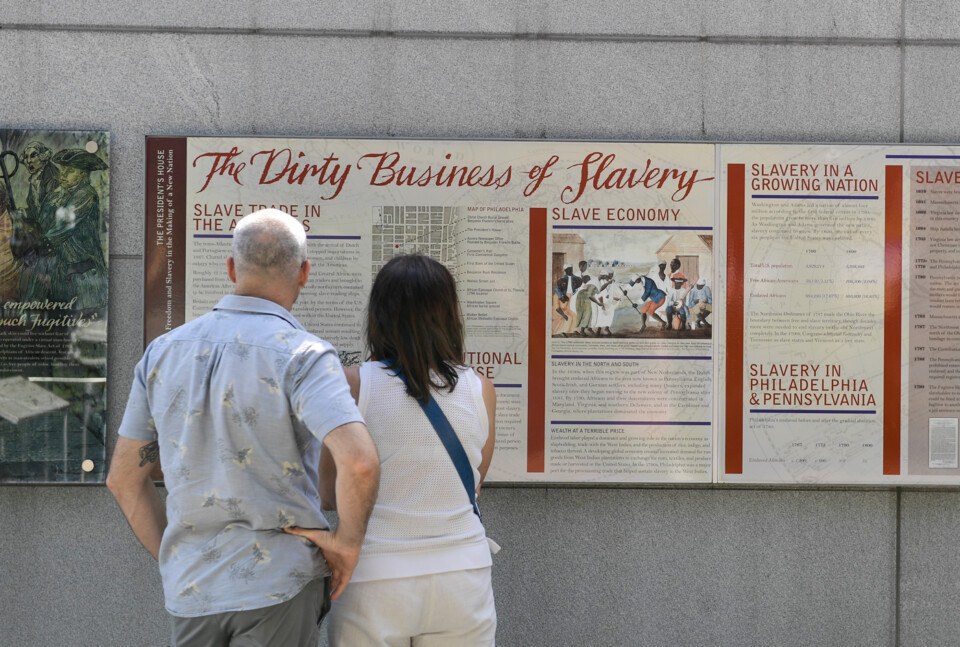

Tourists inspect “The Dirty Business of Slavery” at the President’s House / Photograph by Matthew Hatcher/Getty Images

What was the response to your letter campaign?

Well, Mayor John Street got back to us quickly. He said he knew nothing about the slaves at the President’s House and was going to officially jumpstart this idea of making a slavery memorial there. He kicked in $1.5 million, and we were on the map. Later, Congressman Bob Brady and Congressman Chaka Fattah kicked in $3.5 million. And all of this was to develop a slavery memorial on that space, which would be the first slavery memorial of its kind on federal property in the history of the United States of America. It opened on December 15, 2010.

Everything was great … until last year, when the new guy in the White House began to issue executive orders. And then last month, the slavery exhibit was removed.

Back in 2002, when you undertook this project, had the federal government been receptive to the idea?

Everybody agreed that the story needed to be told, but there were discussions about the matter of degree. To them, this was going to be a George Washington memorial with a very small slavery component. From our standpoint, it was going to be a slavery monument with a small George Washington component. We made an argument about equity, the idea being that there were more statues and memorials and monuments to George Washington than to any other human being in the country. There were literally none, on federal property, that memorialized the slaves.

And you wound up with an open-air exhibit with 34 panels and interactive components that dug deep into the history of slavery.

Yes — as well as a glass enclosure where visitors could stand and look down back in time to 1790 where the foundation was for the kitchen of the President’s House and then look across the President’s House site over to your left on the street level about 30 feet ahead and see the slave quarters, which I would describe as akin to a large doghouse structure. When you walk toward the heaven of the Liberty Bell Center, you literally have to cross the hell of slavery to get into it.

Take us to the present. What exactly happened on January 22nd?

At about 3 p.m., like a thief in the afternoon, vandals assigned by the White House came and stripped down all the interpretive panels. They stripped the monument of its essence. Picture what a giant, magnificent house looks like with lots of luxury furniture in it — and then what it looks like if you remove the furniture. All you have is this shell. Some people say they “peeled” the displays off of the walls. I say that they pried them and put them in storage at the National Constitution Center.

This isn’t just a matter of destruction. This is not just a matter of defiling. This is desecration in the true sense of the word.”

My understanding is that you were able to view them this past Monday along with a handful of other viewers, including the federal judge presiding over the city’s lawsuit against the Trump administration regarding the removal.

Yes. We were allowed to do that, but under the agreement that we could not disclose exactly where the panels are being stored inside the center. But I can say this: While they are on the grounds of the Constitution Center, the particular grounds where they are located are not actually owned by the Constitution Center. I can say that.

I’m imagining them in some kind of temperature-controlled archival room, like a piece of art in storage at a museum.

That’s what I expected, too. But, no. Imagine taking the Liberty Bell and throwing it into some guy’s garage. What they basically did was throw these 34 pieces into Uncle Sam’s garage. They certainly haven’t been destroyed, and I cannot say that they were damaged, but they are in a large garage-type structure. No carpeted floors. Not wrapped in bubble wrap. Cement walls. Cement floors. Disgraceful. This isn’t just a matter of destruction. This is not just a matter of defiling. This is desecration in the true sense of the word.

In its lawsuit against the federal government, the city is arguing that the National Park Service violated an agreement NPS had with the city over how the memorial would be managed and over its very future. That agreement held that the NPS couldn’t just do whatever it wanted with the memorial. But the government seems to be claiming that the agreement no longer applies.

The agreement in question says that the NPS can’t just up and do whatever it wants with the exhibit without collaborating and discussing it with the city. The government owns the exhibit, but not with king-like dictatorial powers. While the case moves through court, the judge has ordered the federal government to make sure the pieces are properly taken care of and not damaged in any way. Meanwhile, the government came up with this ridiculously technical reason that they claim the agreement has expired [city officials are challenging the federal government’s understanding of that agreement] and anytime you are relying on a ridiculously technical argument, it means you have bullshit.

Let’s say the city wins its case. Do the panels go right back up?

No. If the city wins, the government will take the decision to the Third Circuit Court of Appeals, and if it loses there, it would go to the United States Supreme Court.

Is there any kind of potential compromise on this? Or is the only resolution that you and your group will accept the return of the panels to their proper place?

We don’t just demand that the site be restored, we want the site enhanced. More space. More information. And then? Then we want to replicate these all over the country. So in a word, Victor, no, there is nothing we will agree to as a compromise. Based on the public outrage — the public will, the public agitation and the public resistance — we are going to mount such an irresistibly powerful campaign that the federal government will be forced to return the items. People power will reach a resolution. We’ve always had a two-pronged approach based on the lessons learned from the Civil Rights struggle. You need people raising hell in the streets and lawyers raising issues in the courtroom.

What can the average Philadelphian who is horrified by this do to help?

I’m gonna quote this famous philosopher-slash-poet-slash-godfather of hip-hop, the great Gil Scott-Heron. He said, just because you can’t do everything doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do anything. It can be as little as going to the Avenging the Ancestor Coalition’s social media pages and clicking “Like.” Sign our petition. Become a member. Join one of our action teams, like our phone bank or email teams. Join us in the front lines protesting and demonstrating. Fill up the courtroom during hearings. Do whatever you can do. Fight.

To learn more about the Avenging the Ancestors Coalition and upcoming actions to fight the slavery memorial’s removal, visit their Facebook page.

Ask Dr. Mike: Does AI Belong in Healthcare?

Meet internal medicine physician Michael Cirigliano, affectionately known as “Dr. Mike” to not only his 2,000 patients, who love his unfussy brilliance, tenacity, humor, and warmth (he’s a hugger!), but also to viewers of FOX 29’s Good Day Philadelphia, where he’s been a long-time contributor. For 32 years, he’s been on the faculty at Penn, where he trained, and he’s been named a Philadelphia magazine Top Doc every year since 2008. Starting today, he’s our in-house doc for the questions you’ve been itching (perhaps literally) to ask a medical expert who’ll answer in words you actually understand. Got a doozy for him? Ask Dr. Mike at lbrzyski@phillymag.com.

Listen to the audio version here:

Hi again, Dr. Mike! Obviously, people have been using Google and WebMD for a while now to diagnose their health symptoms. And now we have ChatGPT. What’s your stance on all of it?

I said it before and I’ll say it again: “He or she who treats themself, treats a fool.” At the same time, I am all about patients being empowered — and to quote discounted-clothing mogul Sy Syms, “An educated consumer is our best customer.” In other words, knowledge is power, but you need to have some modicum of expertise to help guide you through the shark-infested waters of healthcare.

So, if you want to do a literature search, fine! But if you’re experiencing symptoms X, Y, and Z, you should run it by your doctor who’ll help tease through the nuances. You’re not going to be able to get seen, tested, or treated by ChatGPT, WebMD, and Dr. Google!

Got it. But has AI ever helped you, as a doc?

AI has infiltrated my life, but one way I’ve been using it for good is with this app called OpenEvidence, which is designed for use by healthcare professionals only. It kicks ass! It’s science-based and provides references — like studies and information published in scientific journals like JAMA and the New England Journal of Medicine — for everything it spits out. It has revolutionized how I deal clinically with patients. If I’m worried about a drug interaction or am wondering about what the best diagnostic test is for a certain condition, I’ll check OpenEvidence. It compiles information that’s accurate, to the point, and trustworthy. For me, that has made my practice of medicine better.

Wow, that sounds way smarter than searching symptoms on Google and getting aggregated “answers” that could be coming from totally bogus sources.

Right, and that’s what I worry about! There’s a tremendous amount of misinformation out there — and when it comes to AI, especially for something as important as your health, I use a phrase Ronald Reagan used: “Trust, but verify.”

That being said, I don’t solely rely on an AI-powered app to make my professional decisions. For example, when it comes to a pregnant patient, I will run down the hall to the gynecology department and consult with real people to make sure a medication is okay for a pregnant person to take. The possibility of getting it wrong scares the shit out of me more than anything! You’re dealing with two!

Why do you think people are so eager to take humans out of the equation? What’s the urgency?

I think part of it is that humans make mistakes, and people believe a computer wouldn’t make those errors. And when you’re dealing with life-or-death issues, we typically want every single piece of technology we can get to keep patients alive. But urgency doesn’t mean we should be relying so much on something that, I believe, is still in its infancy.

What about FDA-approved AI technologies that are innovating and assisting with the medical process, like reading X-rays, decoding mammogram results, and even delivering anesthesia? Is this the future of healthcare, whether we like it or not?

I would be very hard-pressed to get into an airplane with no pilot. I don’t care if it’s the most sophisticated computer system on the planet — I’m not getting on that plane. The same goes for healthcare. You need a human involved for two reasons: To get multiple eyes looking at whatever you’re dealing with; and more importantly, to connect with patients on a human level. We need humanity here — healthcare is not an algorithm, and it’s not just interacting with data.

I do think we need to embrace technology to a certain extent, though. If I hadn’t, I would’ve never moved to electronic medical records. Also, humans make mistakes, and maybe that’s where the computer or AI will assist or correct. Maybe there’ll come a time when X-rays don’t need verification by a doctor because the AI software is so good and so accurate.

The bottom line is: I still want a human involved. What happens when your mammogram detects cancer? Do you get an impersonal email saying, “You have cancer. See you later!” and then a robot performs your surgery? I believe wherever we’re headed should be a blend — one that doesn’t solely rely on computers and that doesn’t take the human touch out of the equation. At the end of the day, we need people. When you’re nearing your end, you’re thinking about family and your legacy …

And hopefully a computer screen isn’t the thing in front of you saying, “Alright, time’s up! Goodbye!”

Oh, God! Let’s hope not!

“We Owe You One”: The Sixers, the 1977 NBA Finals, and the Fight for the Future of Basketball

Philadelphia 76ers Julius Erving in action, making a dunk versus the Portland Trail Blazers in Game 2 of the NBA Finals (Philadelphia; May 26, 1977) / Photograph by James Drake/Sports Illustrated via Getty Images

The 1977 NBA season was the first season following the league’s merger with its upstart cousin, the American Basketball Association. With the merger came new players, most notably Julius Erving, who joined the Philadelphia 76ers. Buoyed by Erving and teammates George McGinnis and Doug Collins, the team posted the best record in the Eastern Conference and eventually made its way to the NBA Finals against the Bill Walton-led Portland Trail Blazers.

In this excerpt from the new book Moses and the Doctor, out next Tuesday, author Luke Epplin delves into the 1977 Finals and its racial and societal implications for the country at large.

Epplin will be in town next Tuesday, February 10th, at the Rittenhouse location of Barnes and Noble to talk about his new book with Philadelphia magazine executive editor Bradford Pearson. Tickets are available here.

Shortly before noon on May 21, the day before the 1977 NBA Finals began, the Philadelphia 76ers sauntered into practice loose and relaxed, looking no more troubled than if prepping to face a pedestrian opponent at midseason. Their outfits were as dissimilar as their personalities, a wash of styles and colors. Making it to basketball’s biggest stage hadn’t changed them. They warmed up as they always had: by lofting balls skyward from halfcourt. “We’ve been consistent all season. Consistently unpredictable,” Julius Erving explained. “We are not a blackboard team. I don’t know whether we could have gotten this far if we were. We’ve never believed in orderly practices or doing things by the book.”

Their opponents, the Portland Trail Blazers, had just wrapped up a workout that had unfolded with the precision of a symphony orchestra. In the eyes of Bill Livingston, a sportswriter for The Philadelphia Inquirer, Blazers practices were an “incredible study in intensity and enthusiasm.” Head coach Jack Ramsay, a whistle dangling around his neck, fronted the opening calisthenics himself — a conductor warming up his talent. When the whistle blew, Ramsay demanded absolute attention: no dribbling, no shooting, no ball spinning. Brooking little dissent, he placed his utmost faith in the painstakingly composed offensive and defensive schemes that he expected his squad to execute with minimal deviation. “The players,” Ramsay insisted, “are the medium through which the coach expresses his philosophy. The artist must be in control of his medium, and a coach must prepare his players for their performance.” Blazers guard Lionel Hollins said the team “ran the system so well that it became part of our DNA. We practiced and practiced and went over the same things. Jack [Ramsay] was so detail-oriented. He taught us that details matter.”

Basketball fundamentalists who were uncomfortable with the creeping influence of streetball viewed the Finals matchup as a morality play that pitted two distinct styles against each other: playground versus playbook, freelance versus structure, individual versus team. The Sixers were painted as outlaws, a stormy band of malcontents slapped together by an owner with bottomless coffers and capable of overpowering opponents with extraordinary one-on-one talent. Philadelphia Inquirer columnist Bill Lyon later characterized them as “a non-team for whom passes were something you reserved for your friends at the guest gate.” The Trail Blazers, in contrast, were hailed as purists, selfless practitioners of patterned play and off-the-ball movement. “Teamwork,” Hollins said, “is preached so much that when one of us turns an ankle, we all limp.” For some, the stakes were existential. “Basketball will be set back fifty years if the 76ers ever win,” one unnamed fan declared.

Bleeding through it all was another binary: Black versus white. Race had been baked into mainstream coverage of the 76ers all season long. Rather than lauding the faster, freer, more expressive brand of basketball that had propelled the Sixers into the championship round, the press pathologized it in terms that white Americans often ascribed to the Black inner city: disorderly, brash, unruly, authority-averse. Articles about the club oozed with racially tinged condescension. The cure for the squabbling Sixers, a writer for The Sporting News declared, was “teamwork, character, and a little humility” — in other words, less playground, more deference. The 76ers were an object of both fascination and derision, at once an unmissable spectacle and an emblem of a troubled league that had gotten too Black too fast for its fans’ taste. Reporters fixated on markers of the players’ wealth — their Mercedes and colorful clothes and six-figure contracts — as a means of calling out their lack of hustle, their perceived unwillingness to sully their hands with the dirty work that wins titles. “All season, we’ve been the millionaires in our tuxedoes out there and the other team was carrying its lunch pails,” said Doug Collins, the team’s lone white starter. George McGinnis put it more bluntly: “I think most of white America thought of us as a bunch of bigmouth, cocky, high-priced n****rs.”

At the heart of it was Julius Erving — or Dr. J, depending on how the narrative was framed. The gap between Erving and Dr. J had never been wider. More than anyone, Erving had deviated from the Sixers’ me-first ideology, curbing his creative instincts — he averaged eight fewer points than in his final season in the ABA — to such an extent that at one point he’d mused, “When are you going to see the old Dr. J? Maybe never.” Somewhat echoing the media’s criticisms, he spoke frankly of his club’s helter-skelter approach. “Lots of times we run up and down and I don’t know what’s accomplished,” Erving said during the playoffs. “That’s how we play in games. As far as execution goes, we don’t work on it. That’s why our execution suffers. We’re a fast break team. We create as we go along. You can’t practice that.”

At the same time, there was an alternative narrative that centered on Dr. J in the abstract, the spiky-haired, slickly outfitted leader of the league’s foremost Black club. In this telling, Dr. J had abandoned his home out of greed and latched onto a superteam that closely resembled the outlaw league he’d hailed from. As a result, the stigma of the ABA along with its accompanying racial baggage clung to Erving like an unshakable odor, no matter how much he modeled the team-oriented approach that critics claimed the Sixers lacked.

Erving’s superstar counterpart on the Trail Blazers, Bill Walton, headed into the Finals saddled with baggage of his own. His, however, was spun in wholly different ways. Walton was two people at once: a fundamentally flawless center whose pair of immaculate seasons at UCLA in the early 1970s had thrust him into the national spotlight and a long-haired, tie-dye-clad, left-leaning vegetarian who used to answer his phone “Impeach Nixon,” had been hauled off to jail at an antiwar protest, and had once faced questioning from the FBI about associating with someone connected to the kidnapping of heiress Patty Hearst. “If a black player ever tried any of that stuff, he would’ve been banished from the league,” wrote Darryl Dawkins, cutting to the core of a double standard that cast aspersions on Black players for speaking their minds while affording white players wide latitude.

By 1976–77, his third season in the NBA, Walton had learned to clam up about his off-court endeavors, which garnered him positive profiles of personal growth as he led the league in rebounds and blocked shots. He was a player of such exceptional instincts and vision that he could boost his team without ever putting the ball in the hoop. When Walton was healthy, the Trail Blazers were the best team in the NBA; when he was hurt, they were the second worst.

To his credit, Walton swatted away efforts to portray him as the sport’s “Great White Hope.” But that didn’t stop the media from trying. Too much was on the line to quibble with Walton’s past. In the first postmerger Finals, after the mass injection of ABA talent had scrambled the rhythm and complexion of NBA games, the best shot at reassuring aggravated fans and executives that white team basketball could still triumph over Black expressive individualism flowed through Walton’s club.

Before the start of the opening game on May 22, 1977, Sixers fans welcomed the Trail Blazers to Philadelphia by pelting the players with paper cups — a gesture consistent with a city whose fabled brotherly love had never extended to sporting events. The tipoff heralded what was to come. Sixers center Caldwell Jones batted the ball to George McGinnis, who whipped it downcourt to Julius Erving for a one-handed jam. It was the exact sort of crowd-igniting play that the Blazers had been hoping to prevent. Nearly every time Erving caught the ball, three defenders swarmed him. That didn’t stop Erving from exploding for thirty-three points.

In the end, the Blazers netted more rebounds and assists, but the Sixers fired up more shots, which put them over the top, 107–101. Basking in the victory, Erving lobbed some veiled shots at his critics. “I don’t have anything to prove to anyone,” he asserted, adding, “I was trying to be steady, trying to be a factor, not only with my scoring, trying to have a total consciousness of how I could do the best for my team.”

No game more fully captured the beauty and the bedlam of the Sixers than Game Two. For twenty-four minutes, they flew up and down the court with the speed and brute force of a locomotive. By the time the halftime buzzer sounded, the Blazers found themselves down by eighteen. Even though the lead held in the second half, the drama that had destabilized the Sixers all season once again reared its head. Midway through the fourth quarter, Darryl Dawkins tossed Blazers forward Bob Gross to the floor while the two tussled for a rebound. Popping back up, Gross stomped toward him as if to retaliate, and Dawkins threw a wild left hook that missed Gross but nicked his own teammate Doug Collins above the right eye. Maurice Lucas, the Blazers’ self-appointed enforcer, charged across the court and clocked Dawkins on the back of his neck. Taken by surprise, Dawkins whirled around and put up his dukes like a bare-knuckled boxer. Around them, spectators vaulted railings and poured onto the hardwood. Referees pulled the two fighters apart while security guards chased after Philadelphia fans eager to incite a rumble. In the eye of the storm, Erving plopped down at center court, resting his elbows across his knees, waiting for the familiar gust of anarchy to breeze by.

Ejected from the contest, Dawkins stormed into the locker room, incensed not at Gross, Lucas, or the referees but at his teammates for insufficiently jumping to his defense. Awash in rage, Dawkins toppled two floor-to-ceiling lockers, tore apart a metal fan, bent several folding chairs, and ripped a toilet off its concrete base, spraying water all over. Loose shoes were floating across the floor by the time the game ended. As George McGinnis put it, the locker room looked “like a hurricane had hit a junkyard.”

Clad in a fedora and a cream-colored suit, a carnation peeking from the front pocket, Dawkins ranted to reporters about his perceived betrayal. When Pat Williams attempted to calm him down, Dawkins shoved the Sixers general manager. Decades later, Dawkins was still sore. “What was Doc doing when the tussle started?” he asked. “Sitting his ass down on the court and being an eyewitness.” It was an image that resonated almost as much as the scuffle itself. “When Doc sat at halfcourt, it sent a message: ‘I am part of this team, but I’m not going to get involved in something like this.’ I think that it would’ve been a better look if he’d come over and put a hand on Darryl and tried to break it up,” Sixers backup center Harvey Catchings said, adding, “Once that incident happened, it changed the whole dynamic. The fact that your leading guy stepped away and sat down . . . We’re supposed to be a team, and whether you step in or not, you’re part of the visual. That hurt us.”

Whatever good spirits should have trailed the team to Portland dissolved into dysfunction and backbiting. Following the Sixers’ humiliating 129–107 loss in Game Three, Steve Mix and Joe Bryant jawed at each other about playing time in the locker room, then filled the next day’s newspapers with quotes about their feud. Everything fell flat in the fourth game. The Sixers’ slam-dunk extravaganza played to silence during warmups; their vaunted breakneck offense sputtered. They fell behind 19–4 in the first quarter and never recovered. Abandoning his seat with minutes to play and his team down thirty, Sixers owner Fitz Dixon muttered, “A disaster, isn’t it?”

Desperate for a reset, head coach Gene Shue convened a team meeting at a hotel in Cherry Hill, New Jersey. Over beers and cheese, they reviewed film of their back-to-back losses. “I looked around,” Erving later said, “saw a lot of things going in one ear and out the other. Saw guys’ (minds) wandering. Saw guys going to sleep.” Those were the least of the Sixers’ problems. Steve Mix was nursing a severely sprained ankle, Lloyd Free a cracked rib that had collapsed one of his lungs. Hampered by a painful groin pull, George McGinnis was receiving regular injections of cortisone and xylocaine, which numbed his left leg. He fell into such a dire shooting slump that his teammates had taken to yelling “Brick!” whenever he chucked a jumper during shootarounds. Shue was forced to close his practices to the press to avoid embarrassing comparisons to his opponents’ sessions.

For the first time since he’d dragged the New York Nets to the ABA championship the previous season, Erving took matters into his own hands. He sensed that if the Sixers were to regain the momentum, he would need to take “Dr. J out of the closet.” Erving’s command to his teammates was uncharacteristically forceful: “Unless somebody else is going well, here’s where the ball should come.” Over the next two contests, he hoisted a full 30 percent of the Sixers’ shots, piling up thirty-seven points in the fifth game, forty in the sixth. So fervently did Erving attempt to will Philadelphia to the title that one writer claimed he “resembled a guy pulling a locomotive with his teeth.”

In one memorable sequence, Erving fielded an inbounds pass, dribbled through four Blazers defenders, then threw down a vicious one-handed slam over Bill Walton. Before heading back, Erving flicked the ball off Walton’s back — a small playground gesture of one-upmanship. It was Dr. J’s long-awaited national unveiling, the moment when the oral mythology turned visual, putting to bed any remaining uncertainties about whether Erving’s alter ego had been a smoke-and-mirrors apparition, born of a defunct bush league in which “defense” had been a dirty word.

But it wasn’t enough. Exhausted, Erving sucked air on defense, unable to keep pace with Blazers forward Bob Gross. The Blazers swung the ball around the perimeter until Gross, running Erving through multiple screens, shook free for open jumpers. An eleven-point scorer in the regular season, Gross poured in forty-nine total points in the final two contests, both wins for the Blazers. “Who the hell is Bobby Gross?” broadcaster Neil Funk asked Sixers assistant coach Jack McMahon after the Blazers clinched the championship in six games.

“He’s the guy that just kicked our ass,” McMahon retorted.

In reality, it was a group effort. Consistent with Jack Ramsay’s philosophy of sacrificing individual accolades for the collective good, the Trail Blazers reached near parity on offense — all five starters averaged double digits for the series, with none scoring more than twenty points per game. Erving, at thirty per contest, bested the next closest Sixer by eleven points. “What went wrong with the Sixers,” Bill Walton proclaimed amid the celebration, “was we’re the better team.” A fan-made banner draped across the upper reaches of Portland’s Memorial Coliseum had summed it up neatly: “The Blazers fly United. The Sixers use four planes.” Basketball executives breathed a sigh of relief. Symbolically, at least, the NBA had staved off one final challenge from the ABA.

In the hours after George McGinnis — whose shooting touch had deserted him so fully that he likened himself on the court to “a blind man searching for the men’s room” — had missed a tying shot at the end of Game Six, sealing the Sixers’ 109–107 loss, Erving sprawled out across the locker-room floor, an ice bag perched on each knee. Over and over, reporters took turns asking variations of the same question: what happened? Doug Collins marveled at Erving’s patience and self-control in those circumstances, at his willingness to respond to each query without snapping, “You dumbass, I just answered that question.” Even amid the sting of defeat, Erving managed to puncture the argument that playground basketball had unraveled under pressure, that this was the last the league would see of the attitude and the approach that the ABA had ushered into the NBA. “If we won, you would all be saying that our style is the wave of the future in the NBA. The old Boston Celtics team concept would be a thing of the past,” Erving said. “Now, because we lost, tradition has been upheld and we’re just a bunch of outcasts. One shot in the final minute could have changed that.”

Finally, after every notebook and recorder was full, Erving brushed off the ice bags, slung his gym bag over his shoulder, and shuffled toward the exit. Just then, a reporter for a local Oregon newspaper dashed in with apologies for being late. “It’s OK,” Erving murmured as he dropped his bag to the floor, prolonging the worst night of his professional career out of duty and etiquette.

Fury gripped Philadelphia in the days after the 76ers fell to the Trail Blazers. Everywhere, residents groused about how a club swollen with talent had bickered among themselves while a championship had sifted through their fingers like sand.

For decades, Philadelphia’s professional sports teams had made a habit of frittering away playoff berths and championships, often in excruciating fashion. The Phillies of Major League Baseball would go nearly a century before winning a World Series. In 1964, they held a six-and-a-half-game lead in the National League with twelve games remaining before ten straight losses cost them the pennant. Similarly, the Eagles of the National Football League were in the midst of a title drought that would stretch for more than five decades. Even though the Flyers of the National Hockey League were coming off back-to-back Stanley Cups, they, too, were entering a fallow championship period that persists as of this writing. So when the Sixers dashed out to a 2–0 advantage against Portland, Philadelphians braced themselves not for victory but collapse. In Philadelphia, journalist Jere Longman said, “victory is only defeat that hasn’t happened yet.”

Jerry Selber, a self-professed “basketball freak,” sensed the anger at Norris Square Park in North Philadelphia, where college players and even some ex-pros clashed in sharp-elbowed pickup games. “The prevailing feeling was, this was in our grasp and we got robbed. How the hell did that happen?” Selber remembered.

By day, Selber labored on the creative end of Sonder, Levitt & Sagorsky, the agency that handled the Philadelphia 76ers’ advertising. In the summer of 1977, Selber and his colleague Victor Sonder racked their brains to figure out how to reflect in an advertising campaign the city’s emotional response to blowing the NBA Finals. They settled on the slogan “We Owe You One.” In four words, it conveyed two distinct messages: an apology for the previous season and a promise for the upcoming one. It validated Philadelphians’ gripes while also suggesting that this club somehow was immune to the city’s hard-luck history. The subtext, Selber explained, was that “you fans have a right to a title, and dammit, we’re gonna give it to you.”

Erving harbored misgivings not only about guaranteeing a championship in a fickle profession but also about having to continue fielding questions about losing the last one. When asked if Philadelphians deserved a title, he scoffed, “Are you kidding? Where did we screw up last year? I thought we had the potential to win a championship. We didn’t win a championship, what happened happened. We had a hell of a year. We just didn’t win the championship.” Nonetheless, ever the company man, Erving reluctantly agreed to appear in the television commercial for the campaign.

Toward the end of summer, right before training camp, a film crew set up in the locker room at the Physical Fitness Center at Hofstra University, close to Erving’s house on Long Island. As they began rolling, Erving stared straight into the camera, extended his elongated index finger, and, enunciating each word unhurriedly, uttered the line that would hang like a millstone around his neck into the following decade: “We . . . owe . . . you . . . one.”

This Is the Philly Bar for Seahawks Fans (or Just Patriots Haters) This Sunday

This Sunday, it’s the Seattle Seahawks vs. the New England Patriots in Super Bowl LX, and Philadelphia bar Sonny’s Cocktail Joint is going all-in for the Seahawks (Photo by Chris Graythen/Getty Images)

This Sunday, the Bad Bunny concert — otherwise known as Super Bowl LX — will start at 6:30 p.m. in lovely Santa Clara, California. The Seattle Seahawks (14-3) are set to face off against the New England Patriots (also 14-3), 11 years after the one and only other time that the two teams played each other in the Super Bowl, a game that saw the Patriots victorious with a final score of 28-24. And one Philadelphia bar owner is taking this opportunity to show just how much he, like many of the rest of us, hates the Patriots.

Best of Philly-winning Sonny’s Cocktail Joint (yes, this is the bar across from Bob & Barbara’s that has in its short history a fire that closed it followed by a flood that closed it after it reopened) has decided to go all-in for the Seattle Seahawks on Sunday, declaring itself a Seahawks bar — notably, for that one night only.

“I fucking hate the Patriots,” says Sonny’s Cocktail Joint co-owner Chris Fetzfatzes, who is also behind South Philly’s Grace & Proper and the late brunchery Hawthornes (RIP). “Tom Brady is a wiener. The whole franchise is a wiener. The Patriots beat us. And the Patriots beat Seattle. So always, always, always, it’s fuck the Patriots.” (Former Patriots quarterback Tom Brady is, of course, no longer involved with the Patriots, but the hatred for the Patriots will linger for years to come thanks to the team’s previous association. In point of fact, Brady is now a minority owner of the Las Vegas Raiders and says he is not rooting for the Patriots in this Super Bowl.)

A coaster at temporary Seattle Seahawks Super Bowl bar Sonny’s Cocktail Joint (photo by Laura Swartz)

So what does becoming a Seattle Seahawks bar for the Super Bowl and only for the Super Bowl mean exactly? Fetzfatzes explains that there will be Seahawks colors represented by balloons and other decor. Plus, Seahawks swag and some relevant menu additions.