The Next Big ALS Breakthrough Could Be Developed in Philly

Unlike many diseases, there’s one refrain you never hear in the ALS world: You can beat this. ALS, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, is an incurable neurodegenerative disease that affects nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord.

“The main thing is just knowing it’s gonna get worse,” says Donna Trantina, an Elkins Park resident who has been fighting the progressive disease since 2020. “It’s not going to ever get better, it’s only going to get worse or maybe, if you’re lucky, you’ll plateau.”

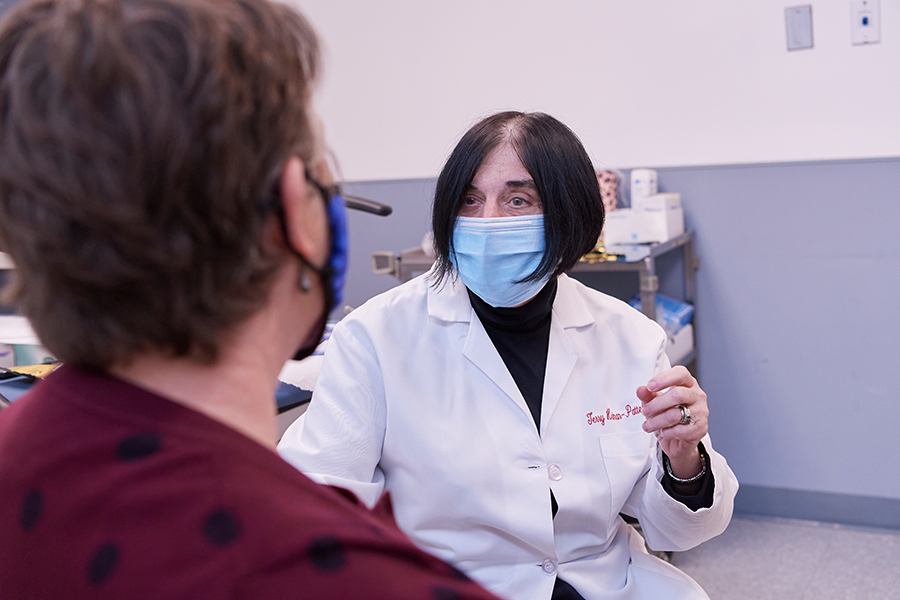

Trantina is one of thousands of patients from across the country who have sought treatment — and the opportunity to participate in a number of clinical trials — at the Temple ALS Center of Hope. Founded by Dr. Terry Heiman-Patterson, the center is one of the leading hubs in the country developing a better quality of life for patients with ALS to live through both treatment and research.

Their work ranges from basic research, which is typically conducted on mice, to clinical trials, often testing new drug protocols. Heiman-Patterson says those clinical trials represent the best hope at slowing a patient’s disease progression. That’s why she approaches her work with a constant sense of urgency, even though she’s been in the field for decades.

“First and foremost, the most important thing we do is take care of people. Everything else is icing on the cake,” Heiman-Patterson says. “But if I don’t push clinical research, develop new drugs, and explore new tools and ways to use the tools that we already have better, then I’ll be doing the same thing 10 years from now. Providing patients what they need and developing new treatments for the future go hand-in-hand.”

The Biomarker Breakthrough

One of Temple’s most significant areas of ALS research centers around biomarkers, which have the potential to revolutionize drug protocols for patients by catering treatment to a patient’s distinct genetic or molecular characteristics. Because ALS is not one disease, but rather a collection of diseases, biomarker research can be key to figuring out what characteristics make some patients respond well to drugs that have no impact on other patients.

For example, if a drug is given to 100 random ALS patients in a trial and only 10 respond, the drug would typically be seen as not effective. But by surveying biomarkers, a researcher may be able to find that those 10 patients all have neuroinflammation, and the drug could be very valuable for treating other patients who also have neuroinflammation.

As part of this research, Heiman-Patterson is very active in what’s called tissue banking, where she collects samples from patients with ALS. In addition to collecting samples of spinal fluid, serum, blood plasma and more, she and other ALS researchers collaborating on this work are recording a wide range of patient characteristics.

“Were they slow or rapid progressors? Women or men? Did their disease start with what we call ‘bulbar onset speech’ and swallowing or limb issues? How old were they when it started?” Heiman-Patterson says. “All of that clinical data needs to be captured with the specimens.”

AR Meets Healthcare Innovation

Another research and development priority for the Temple ALS team is around assistive technology. Currently, Temple is exploring how augmented reality (AR) glasses could help patients operate a smart system such as Google Home independently, allowing them to turn on a fan, the tv or more with their eyes. The AR research evolved out of a $25,000 clinical setup involving an electrode cap that took 45 minutes to put on the patient.

“Of course, this is not pragmatic for somebody wanting to be independent,” Heiman-Patterson says. “So the objective of our work has been to get something portable and practical and lower cost.”

That led them to develop a smaller, cheaper system based around dollar store glasses with a $10 LCD screen pasted in them and a single-board computer. The total cost of the new setup? Under $1,500, more than $23,500 less than the original offering. Heiman-Patterson says they’re now working on systems that will turn the glasses on and off independently using a muscle twitch.

“There are lots of systems for disabled folks who can use voice activation,” she says. “But some of our folks with advanced ALS can’t talk; they can’t move. So we’re making something that can be individualized to the patient and easy for them to use.”

Putting Quality of Life Front and Center

Through all of the Center’s work, Heiman-Patterson says they always remember who their “stakeholders” are: people living with ALS. To that end, the Center uses every tool and expert possible to take care of their patients: physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech and language pathology, breathing tests, cognitive testing, mental health and social work support, and more. They also offer equipment and technology that helps patients stay as independent as possible throughout the disease’s progression. The goal is to keep patients’ quality of life as high as possible for as long as possible, even if clinical trials do not work out for them.

“The problem is, pragmatically, that when I’m sitting with a patient that has ALS, all of the stuff that we’re doing now may not make a difference for them,” she says. “But hope can go very far in helping them, so I really try to present a positive attitude that gives them hope and keeps them living for as long as they can and with the best quality of life as they can.”

For families like Donna and her husband of 31 years, Ken Thomas, that perspective has been invaluable.

“Dr. Heiman-Patterson is very empathetic,” Donna says. “With this disease, no one can know exactly how it’s going to go, but she knows how hard it is and she’s very sensitive not only to the condition, but also to our mental health and helping us deal with this. Because it’s a very long road that you have to travel.”

Donna’s journey continued in late February when she received word that a clinical trial she had been involved in was ending as the drug had been found to be ineffective. After taking a few weeks to let it clear her system, she met with Heiman-Patterson to discuss a new trial. Fortunately for patients today, there are many options.

“When I started working in ALS 40 years ago, we had no drugs that slowed the progression of the disease, and clinical trials were extremely few and far between,” Heiman-Patterson says. “Today, we have many drugs coming down the pike, and Temple is running four or five clinical trials at a time. So I think that now more than ever there is hope. There are options. And what’s important is that we’re going to make the quality of your life, for as long as it might last, as good as it can be.”

This is a paid partnership between Temple Health and Philadelphia Magazine