3 Signs Your Child Might Have Executive Function Challenges — and What You Can Do to Help Them

Courtesy of Woodlynde School

Last school year, parents were a part of their kids’ education like never before. Virtual schooling gave them the opportunity to observe their daily learning style — where they thrived and where they struggled. If you found your child had trouble focusing, staying on task, turning in assignments or keeping their classwork organized, it could be a sign of executive function challenges.

“If your student really struggled with asynchronous virtual learning, that could be an indicator that they’re having a hard time managing their time and materials or finding the drive needed to start and complete tasks,” says MaryBeth Spencer, Head of Middle School at Woodlynde School, a private school in Wayne that has taught students with learning differences since 1976. “If parents don’t know what executive function challenges look like, it can be very frustrating.”

At Woodlynde School — just a 45-minute drive from Philadelphia — teachers and administrators design strategies to mitigate any learning differences your student might have and work with them to achieve success in the classroom. Teaching students with dyslexia, dysgraphia, dyscalculia and ADHD has been the school’s forte since its founding. It’s the reason Woodlynde is one of the nation’s only Wilson® Accredited Partners, which means they can teach students and train teachers in the Wilson Reading System®, a highly regarded structured literacy program.

In recent years, however, Woodlynde dove deeper than ever into curating learning spaces and practices that meet the needs of students who struggle in school but may not have a clearly defined learning difference. Where most of these students have trouble is with executive functioning.

Concerned your child might have executive function challenges? Here are three signs to look for and expert strategies to help them according to the team at Woodlynde.

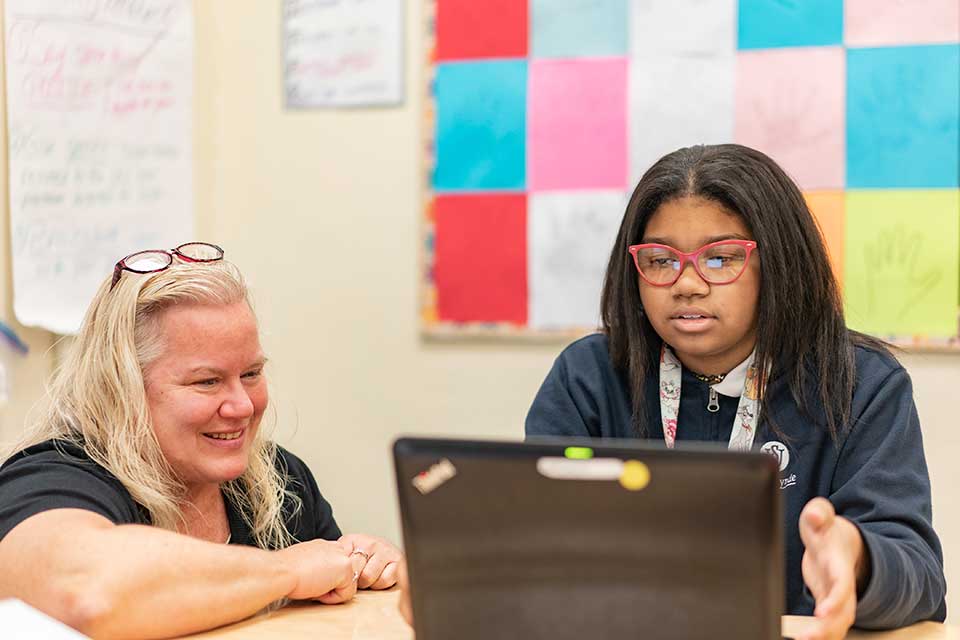

They Have Difficulty Completing Assignments Without Your Help.

Executive functions are often referred to as the brain’s command center. When it comes time to learn, executive functions are what guide us. If, for example, a child has displayed a willingness to learn but is incapable of completing an assignment without outside guidance, it could be an indicator of an executive function problem. Many students with this deficit lack the ability to move from Point A to Point B when it comes to the steps needed to complete an assignment. Often, they’ll need an adult to open a book to a certain page or sit with them while they’re completing their homework.

“We approach these kind of difficulties in the same way we use Wilson® to address trouble with reading and writing,” explains Christopher Kramaric, Woodlynde School’s Director of External Affairs. “We train students using evidence-based methods to systematically build the kind of skills that help them succeed.”

Courtesy of Woodlynde School

Woodlynde relies on ‘direct instruction’ to teach students these techniques. It’s a method whereby teachers model a learning outcome and teach in small steps, encouraging practice after each until kids can work independently.

“Your English teacher at Woodlynde doesn’t just ask you what the tone of that particular Shakespearean passage is,” Kramaric says. “Instead, if a question like that appeared on a worksheet, it would be preceded by four or five others. These are questions — and maybe even page numbers — that guide your practice of answering a question that requires multiple data points across a text.”

In this way, Woodlynde goes beyond what’s taught in a typical classroom.

“This way, you didn’t just learn something about English literature, you also learned an effective strategy for answering a literary question,” Kramaric explains.

Seemingly simple teaching tools like this are paired with digital solutions, too. Just this year, a team from the University of Pennsylvania began piloting an app with Woodlynde’s eighth graders that integrates with the school’s online learning platform. Now, homework and class assignments can be displayed without distractions and alongside a series of timers, rewards and nudges that encourage accountability.

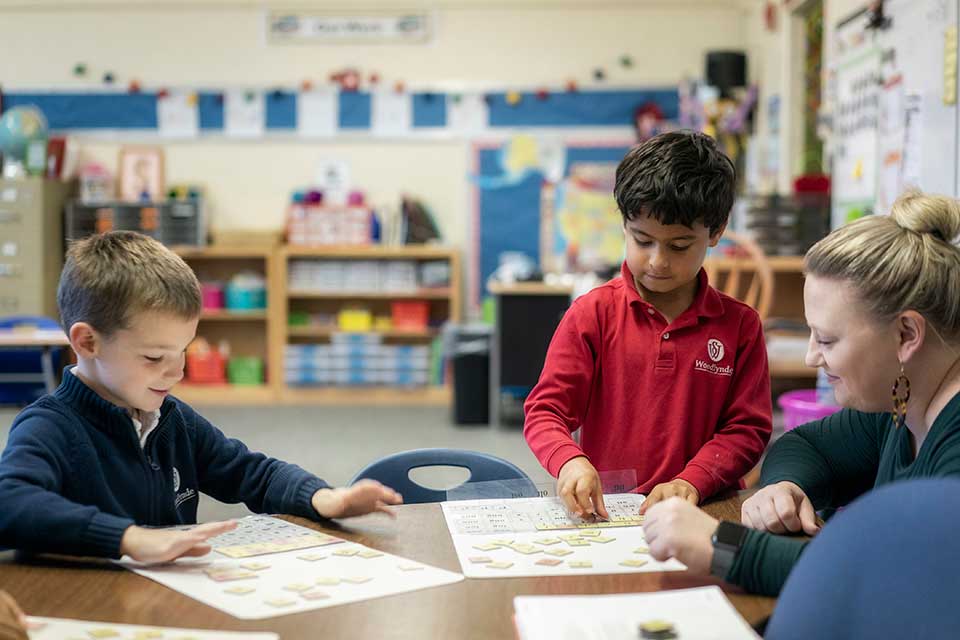

They Can’t Seem to Remember Something They’ve Already Learned.

If you find that your child has difficulty remembering what they’ve learned or defaults to automatic answers almost without thinking, it could be a sign of an executive function deficit.

“Often, students’ attention isn’t present and they struggle with phases of working memory — remembering what new information they’ve learned or where they are in a task,” Spencer says. “These are the students who get lost in the middle of a long division problem even though you know they know how to do it. They lose themselves halfway through.”

To combat these issues, Woodlynde School has small class sizes for hands-on student instruction and assigns each student to one of its learning specialists on staff. These specialists are well-versed in strategy and skills-building and put together individualized learning plans for every student who comes through Woodlynde’s doors.

Courtesy of Woodlynde School

“It might be that a student needs to underline and re-read instructions multiple times or ask themselves a specific prompting question before every long division problem,” Spencer says. “It’s those tips and tricks that our learning specialists identify, record and implement with our kids in their classrooms.”

In order to push further into the latest research on teaching students with executive functioning issues, all Woodlynde teachers and learning specialists are now training under experts in the field from around the country as part of a multi-year program the school recently started.

“We change results for our students in school and beyond by investing in teacher training,” Kramaric says.

They Never Seem to Have What They Need With Them.

Students with executive function issues have trouble keeping track of personal items and are prone to misplacing things. This means when it comes time to sit down and write an essay or fill in a timeline, they often don’t have what they need with them.

“If you can’t set up your physical workspace with the tools you need to complete the task at hand, you can’t even begin, let alone succeed,” Spencer says. “Woodlynde teachers work to solve that problem. When a Woodlynde student enters a classroom, they’ll sometimes see a slide on the Smartboard that reads, ‘prep your space,’ with a photo of what their workspace should look like.”

Courtesy of Woodlynde School

The school, rather than responding to a failure, bakes the habits and practices students with executive function challenges need right into their everyday way of doing things.

“We model outcomes for our students,” Kramaric says. “We give students the tools they need to tackle the challenges in front of them and advocate for themselves. When they leave Woodlynde and go off to college, they feel confident and assured that they can succeed there.”

For more information on how Woodlynde School assists students with executive function challenges, head here.

This is a paid partnership between Woodlynde School and Philadelphia Magazine