Whatever Happened to…Northern National Bank?

We welcome to these digital pages GroJLart, author and editor of the blog Philaphilia, who chronicles Philadelphia history and development in a spicy way. In this ongoing series, GroJLart writes about buildings that have been lost to the wrecking ball or otherwise suffered ignominious fates. — Ed

Northern National Bank

2300 Germantown Avenue

Philadelphia, PA

Holy crap!!! Image from the Athenaeum of Philadelphia.

The worst kind of lost building is one that survives and keeps on truckin’, only to get unceremoniously demolished in the end. This, the Northern National Bank, is the quintessential exemplar of this phenomenon. A building that kicked ass all over the place until getting ripped the f down like a rotten old wooden shed.

The neighborhood that was once home to this bank saw an explosion of growth in the 1870s and ’80s, when factories started locating here and modest 2- and 3-story rowhouses were built to house their workers. At this point, this was a rather mundane neighborhood, filled with block after block of identical rowhouses with a church, school, or factory breaking up the monotony here and there. Where most saw your standard working class North Philly neighborhood of the late 19th Century, real estate monger Edward T. Tyson saw dollar signs.

Big Eddie T figured that with a little extra flair and a few neighborhood amenities, this young neighborhood could be the next big destination for the nouveau riche that were continuously spreading outward from North Broad Street. In the late 1880s, Tyson would go on to build much fancier 3 story rowhouses all over the neighborhood. They were a lot like the homes that were already there, but were imbued with exubarantly decorated facades and much finer interior furnishings. Tyson even went as far as moving into the neighborhood himself, living in three consecutive houses of this type on the 2200 block of Germantown Ave, now the site of a big-ass mural.

Despite the level of luxury these embellished rowhouses achieved, they were still a hard sell for Tyson. After all, folks who would buy these houses would have a lot of money, and they would need a place to put it. The closest bank was ten muddy horse-poop filled blocks away. Tyson, always the badass, had a solution. He would start his own damn bank and run it out of one of his three houses. He called it the Northern National Bank after its location in North Philly, obviously not aware that there was already a buttload of banks going by that name scattered across the country. As soon as the doors swung open on January 4th, 1890, the bank began its trailblazing success.

As it ends up, it wasn’t only the rich who needed a bank. The factory workers living in the hundreds of rowhomes in the surrounding 10 block radius were desperate for a place to deposit their pennies. Edward Tyson, who declared himself president, made banking his main focus, only continuing his real estate efforts as a hobby. It seems he didn’t even care about the nouveau riche anymore– he had plenty of clients without ’em.

Only about a year after the Northern National Bank opened, Tyson was ready to take it to the next level. After all, his new bank received $150,000 in deposits in its first year, a year when other well-established banks were failing left and right. He took a triangular plot of land he owned at the six-point intersection created by the confluence of 7th Street, Dauphin Street, and Germantown Avenue, no doubt originally slated for some of his fancy homes, and started putting together plans for a great building that would be a new locus of the community.

Tyson had his mind set on making this new bank building the most badass in town… a town that already prided itself on having the best-looking banking houses anywhere. He took a big gamble by commissioning Walter D. Smedley for the job. Smedley was a relatively well-known architect of the period but had never designed a bank before. For his much-anticipated bankitecture debut, Smedley pulled out all the stops.

His design was unlike any other bank in the city (or anywhere else, for that matter). The Romanesque Revival structure started from the ground with a heavy pink granite base that would lead up to a facade of thin yellow bricks, interrupted with terra cotta-trimmed arches with details all over the place. The triangular building had a beautifully rounded edge facing the six-point intersection where a grand entrance stood at the top of a huge stairway that made it seem like you were about to enter Valhalla every time you walked through. As if that wasn’t enough, pressed tin decorations and terra cotta cartouches found their way onto the facade as well. The entire package was capped under a metal roof with a ridiculously embellished cornice.

Construction started in late 1892 and continued all the way through 1893, the year written in terra cotta on the facade. When it opened in April of 1894, people lost their damn minds. This place was nicer than most of the great long-operating banks found in Philadelphia at the time. The interior featured a two story open-planned banking floor made of marble. The teller windows were behind cages of bronze. Edward Tyson made a wood-paneled office for himself on the wrought iron mezzanine. What made this even more impressive was the fact that this massively expensive and successful bank building was built in a year when 500 other banks had failed.

The bank would go on to be the ONLY bank operating in the neighborhood for the next five decades. The public was so impressed with Smedley’s outrageously awesome design that he got another major bank commission almost immediately. The West Philadelphia Trust Company, located at the six-point intersection at 40th, Lancaster, and Haverford, was the sequel to the Northern National Bank. It still stands, but is criminally underutilized.

Long after Edward T. Tyson’s demise, his dream lived on. Northern National Bank lasted all the way up to 1929, when it was absorbed by the Ninth National Bank. Ninth National Bank was itself absorbed by the Philadelphia National Bank in 1951. The building continued to operation under its original function until 1971. Though this long life is not all that unusual for a bank building of this type, this one was unique. Through those 77 continuous years as a bank, there was not one renovation or alteration of the interior of the building. By the time it closed (as a bank), the old Northern National Bank was one of the only Victorian-era bank buildings to have its original interior details.

Philadelphia National Bank was nice enough not just to board up the place and split– on February 22, 1972, they donated the building to a local organization, the Ile-Ife Black Humanitarian Center. Ile Ife, which means “House of Love”, is a location described as the starting point of the creation of the world in the Yuruba creation myth. This organization, which promotes African and African-American Culture, turned the old bank into the Ile-Ife Museum. This musuem, which claimed to be the first African American Museum in Pennsylvania, displayed art and artifacts that created a timeline showing the progression of African people from West Africa to the Caribbean to modern African-Americans today.

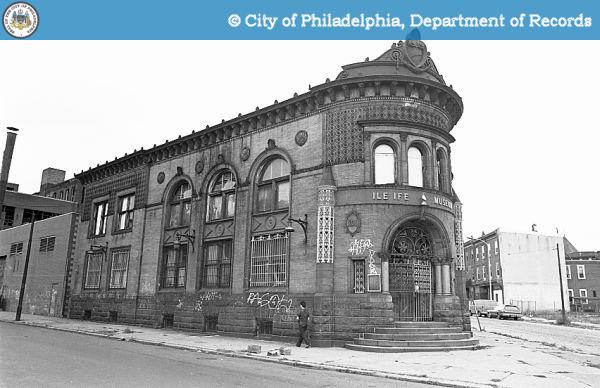

As the Ile-Ife Museum. Image from PhillyHistory.org, a project of the Department of Records.

As the Ile-Ife Museum. Image from PhillyHistory.org, a project of the Department of Records.

The old Northern National Bank was nominated for the Philadelphia Historical Commission Register in 1974 but was rejected. Then, in 1985, a nomination for the National Register of Historic Places turned out successful. As we all know, however, these registers don’t mean dick. After the Ile-Ife Museum closed in 1988, the building was abandoned for the first time in its long life. Over the next nine years, the building was trashed inside and out. It was covered in graffiti and became a major piece of blight in the neighborhood. After all that time in use being preserved down to its last stick, the building became an imminently dangerous pile of trash in 1997 and was demolished.

The building in its last days. Image by Susan Babbitt (Creative Commons License)

Today, the location remains an empty lot, still owned by the Ile-Ife, which is now based in Searsport, Maine. The property has been tax delinquent for 23 years. The neighborhood, which inspired the dreams of Edward T. Tyson, is one of the most depressed-looking parts of the city. Even today, the closest bank branch is 5 blocks away.