Charles Barkley’s Philadelphia Black History Month All-Stars: Part 3

A closer look at Black Philadelphians whose ideas, work, and courage left a lasting mark on our city

Philadelphia’s Black history is vast, visionary … and too often reduced to a handful of familiar names. So, a few years ago, The Philadelphia Citizen asked none other than Charles Barkley to help widen that lens: to spotlight Philadelphians whose influence reshaped science, culture, politics, and more, even if their names never made the textbooks.

See past installments:

This month, we’ll be sharing a group of Barkley’s “Philadelphia Black History Month All-Stars” each week. Consider it a reminder, maybe — and an invitation — to keep expanding the story of who shaped this city.

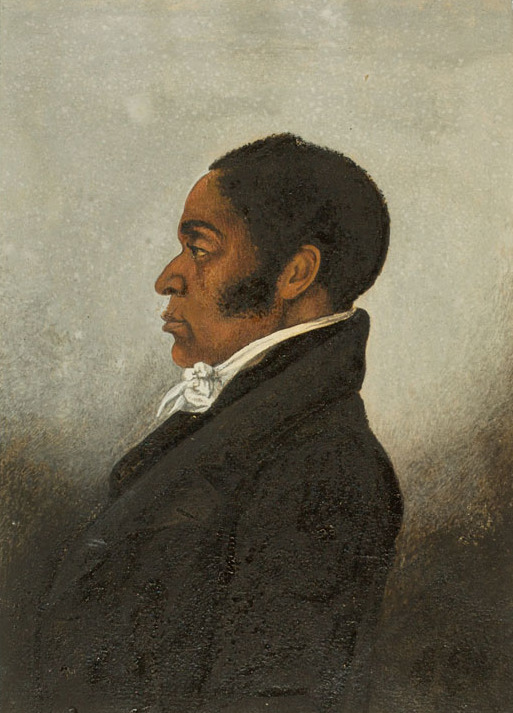

James Forten

Image via The Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Businessman

September 2, 1766 – March 4, 1842

Has the God who made the white man and the black left any record declaring us a different species? Are we not sustained by the same power, supported by the same food … And should we not then enjoy the same liberty … ?”

A sailmaker with a bustling business that employed both Black and white workers, Forten was one of the wealthiest Philadelphians of his time — of any race.

He used his position and his fortune to fight slavery, and to demand civil rights for African Americans, successfully leading the fight against a Pennsylvania bill that would have required new Black residents to register with the state.

Born free in Philadelphia, Forten was largely self-taught: He dropped out of school at age nine to work full-time to support his mother and sister. As a privateer on a ship that got caught by the British during the Revolutionary War, he escaped enslavement by impressing the captain, who ensured he was treated the same as white prisoners of war.

He was released seven months later and walked back from Brooklyn to Philadelphia, eventually becoming an apprentice to sail-maker Robert Bridges, who passed the business on to Forten.

In 2023, the Museum of the American Revolution devoted a special exhibit to Forten and his family.

Charlotte Forten Grimké

Writer/Teacher

August 17, 1837- July 23, 1914

I shall dwell again among ‘mine own people.’ I shall gather my scholars about me, and see smiles of greeting break over their dusky faces. My heart sings a song of thanksgiving, at the thought that even I am permitted to do something for a long-abused race, and aid in promoting a higher, holier, and happier life on the Sea Islands.”

Born into a wealthy family in Philadelphia (she was the granddaughter of James Forten, above) that valued both intellect and activism, Charlotte Forten Grimké was always eager to educate and engage a deprived African American community.

She was the first Black northerner to go south and teach former slaves. During the Civil War; on Union-occupied St. Helena Island, she taught ex-slaves as part of the Port Royal Experiment. While there, she struggled to connect with the islanders who hardly spoke English and who struggled following the daily routines of school.

Nevertheless, once she detailed her experiences in an article published by Atlantic Monthly, more schools started popping up in the south for African Americans. She was also an avid writer, keeping journals that have drawn attention for their insightful take on America during and after slavery.

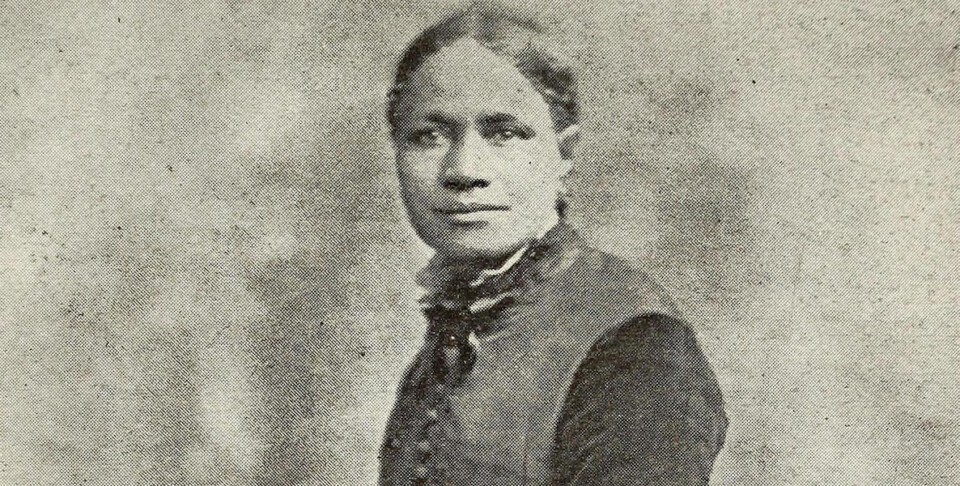

Frances Ellen Walker Harper

Writer

September 24, 1825 – February 22, 1911

The true aim of female education should be, not a development of one or two, but all the faculties of the human soul, because no perfect womanhood is developed by imperfect culture.”

Harper, a writer, abolitionist and suffragist, was born free in Baltimore in 1825, and spent most of her adult life in Philadelphia, where she was active with the Underground Railroad. (She helped escaped slaves make their way to Canada.)

She published her first book of poetry at age 20. She’d go on to publish more than 11 books of poetry and fiction, including Iola Leroy, one of the first novels published by an African American. Her writings primarily focused on social issues: education for women, miscegenation as a crime, temperance and social responsibility.

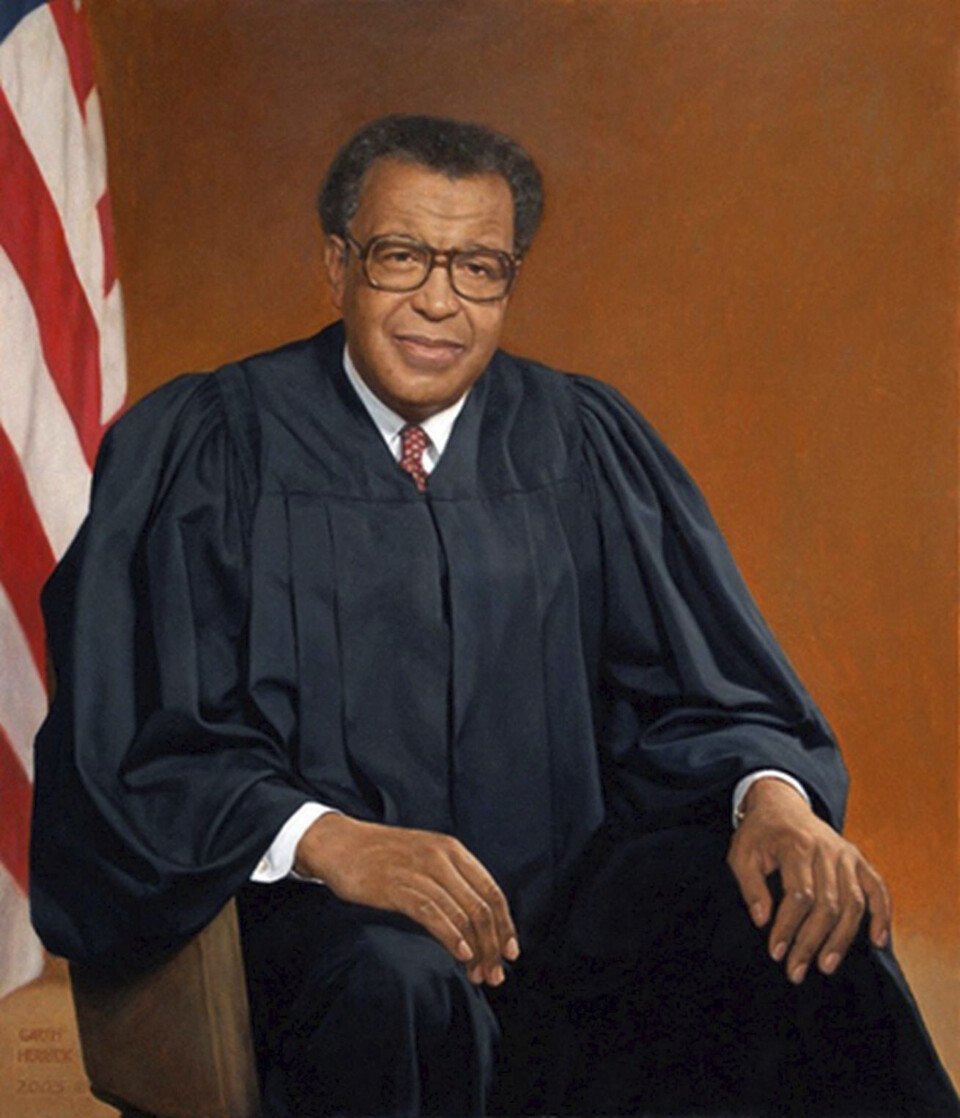

A. Leon Higginbotham Jr.

A. Leon Higginbotham / Photograph via Circle Archive/Alamy

District Court Judge

February 25, 1928 – December 14, 1998

My father was a laborer. My mother was a domestic. And I climbed the ladder and I didn’t come to where I am today through some magical vein. So I am willing to match you, any hour, any day, in terms of the perception of the real America.”

A district court judge appointed by President Jimmy Carter in 1977 — the first African American to hold the position — Leon Higginbotham was a jurist, a scholar, and an orator. He was first Black appointee to a federal regulatory body when President Kennedy placed him on the Federal Trade Commission, and was Philadelphia’s first African American assistant district attorney.

He was a voice for the downtrodden who never shied away from a fight. Winner of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, Higginbotham was a trusted adviser to both South Africa’s Mandela and President Lyndon B. Johnson, a trustee of Penn and Yale, and a civil rights pioneer who, almost by sheer force of will and intellect, bent the arc of the moral universe toward justice.

In 2022, after a fundraising effort led by The Philadelphia Citizen (owned by Philadelphia magazine’s parent company, Citizen Media Group), Penn Carey Law School, and Mural Arts Philadelphia, a mural honoring Judge Higginbotham was unveiled at 46th and Chestnut streets.

Read more about A. Leon Higginbotham here.

Caroline LeCount

Teacher/Civil Rights Activist

c. 1846 – January 24, 1923

Colored children should be taught by their own.”

A teacher in Frankford, LeCount was Philly’s Rosa Parks 100 years before the Montgomery bus boycott, defiantly riding street cars and filing petitions to have a law against Black riders repealed.

With her fiancé Octavius Catto, she kept up the fight even after the law was changed: When a conductor refused to stop for her, LeCount — just 21 at the time — filed a complaint with the police, eventually forcing the driver to pay a $100 fine.

She also pushed for the rights of African American teachers and students, standing up to the school board of the Wilmot Colored School to insist a Black colleague become principal because “colored children should be taught by their own,” reports noted.

Joyce Craig Lewis

Firefighter

June 7, 1977 – December 9, 2014

In 2014, Joyce Craig Lewis became the first female firefighter in Philadelphia to die in the line of duty, while trying to save an elderly woman during a house fire in West Oak Lane.

Lewis knew she wanted to be a firefighter from the time she was five years old, watching as firefighters passed by her house at Ridge and Midvale in the Northeast. Lewis served on several engines and ladders for the Philadelphia Fire Department, including Engine 9, Engine 45, Ladder 21, and Engine 64.

The Philadelphia Fire Department and Club Valiants, an association for Black firefighters, paramedics and emergency medical technicians, honored her with a tombstone shaped like a firefighter’s badge.

Alain Leroy Locke

Writer, ‘Dean’ of Harlem Renaissance

September 13, 1885 – June 9, 1954

Art must discover and reveal the beauty which prejudice and caricature have overlaid.”

A writer and philosopher, Alain Leroy Locke is considered the philosophical architect of the Harlem Renaissance, a less widely known — but no less important — figure than stars Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes.

The first African American Rhodes Scholar (and last to be selected until 1960), Locke graduated from Central High School and then Harvard University.

Despite his talents, even in England Locke faced adversity. Gay and Black, he was rejected from many schools once he arrived at Oxford University because of his race, and had trouble finding work once he returned home. But he triumphed, teaching and leading at Howard University for 42 years.

Sixty years after his death, in 2013, his ashes were buried in the Congressional Cemetery, where his tombstone reads: “1885–1954 Herald of the Harlem Renaissance Exponent of Cultural Pluralism.”