Charles Barkley’s Philadelphia Black History Month All-Stars: Part 2

A closer look at Black Philadelphians whose ideas, work, and courage left a lasting mark on our city

Philadelphia’s Black history is vast, visionary … and too often reduced to a handful of familiar names. So, a few years ago, The Philadelphia Citizen asked none other than Charles Barkley to help widen that lens: to spotlight Philadelphians whose influence reshaped science, culture, politics, and more, even if their names never made the textbooks.

This month, we’ll be sharing a group of Barkley’s “Philadelphia Black History Month All-Stars” each week. Consider it a reminder, maybe — and an invitation — to keep expanding the story of who shaped this city.

Guion Bluford

Astronaut/Scientist

Born November 22, 1942

I’ve come to appreciate the planet we live on. It’s a small ball in a large universe. It’s a very fragile ball but also very beautiful. You don’t recognize that until you see it from a little farther off.”

The first African American to go into space is Philadelphia’s own Bluford, 79, who grew up here before earning an aerospace engineering degree from Penn State through the Air Force ROTC program.

After flying 144 combat missions in Vietnam, Bluford became the first African American NASA astronaut in 1979, eventually going into space on the Challenger and Discovery.

Bluford logged over 28 days in space and 5,100 hours on different fighter pilots. After his retirement, Bluford joined the private industry, eventually becoming president of Aerospace Technology, an engineering consulting firm.

Nellie Rathbone Bright

Teacher / Poet / Author

March 28, 1898 – February 7, 1977

I want to slay all the things just things

That they tell me I must do.

I would drown them all in the tears I weep

When each breathless day is through.

…

I want to look deep in a pool at night, and see the stars

Flash flame like the fire in black opals.”

A devoted teacher and principal, Nellie Rathbone Bright was part of the Harlem Renaissance, through her role in the Black Opals, a literary group that published a magazine of the same name from Philadelphia. (The name pays homage to her poem from its first issue.) Like similar groups in other East Coast cities, the Black Opals were considered an extension of the Harlem Renaissance.

Bright and her family were part of the Great Migration, as they moved from Savannah, Georgia, to Philadelphia when Bright was 12. While studying at Penn, Bright was a founding member of the Gamma chapter of the university’s first Black sorority, Delta Sigma Theta.

A landscape painter who was fluent in Spanish and French, Bright also studied at the Sorbonne, University of Oxford, University of Vermont, and at the Berkshire School of Art in Massachusetts. She co-authored the book American – Red, White, Black, Yellow, with her longtime colleague Arthur Fauset, which focuses on the history of minorities in the United States.

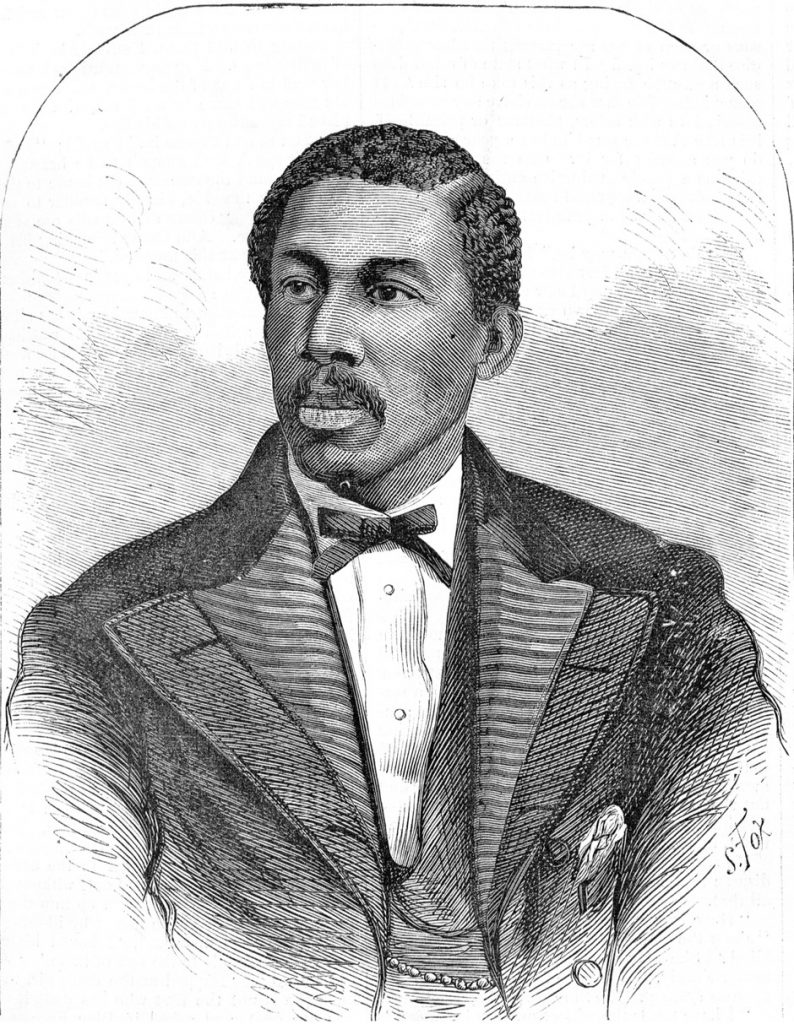

Octavius V. Catto

Civil Rights Activist

February 22, 1839 – October 10, 1871

All that [the colored man] asks is that there shall be no unmanly quibbles about entrusting to him any position of honor or profit for which his attainments may fit him.”

Octavius Catto was the greatest civil rights leader in post-Civil War Philly.

A statue honoring Catto on the southwest apron of City Hall was unveiled by Mayor Jim Kenney in the spring of 2017. It is Philadelphia’s first public statue honoring a solo African American.

Catto was an educator, athlete, and major in the Pennsylvania National Guard. “The Jackie Robinson of his time,” Catto helped establish Negro League Baseball and ran the undefeated Pythian Baseball Club of Philadelphia that played the first black versus white game. He was married to noted teacher and civil rights activist Caroline LeCount. He recruited African Americans to serve in the military and led a successful protest to integrate Philadelphia’s horse-drawn streetcars.

Catto was assassinated on Election Day in 1871, as Blacks fought for the right to vote.

“We shall never rest at ease, but will agitate and work, by our means and by our influence, in court and out of court, asking aid of the press, calling upon Christians to vindicate their Christianity, and the members of the law to assert the principles of the profession by granting us justice and right, until these invidious and unjust usages shall have ceased,” Catto said.

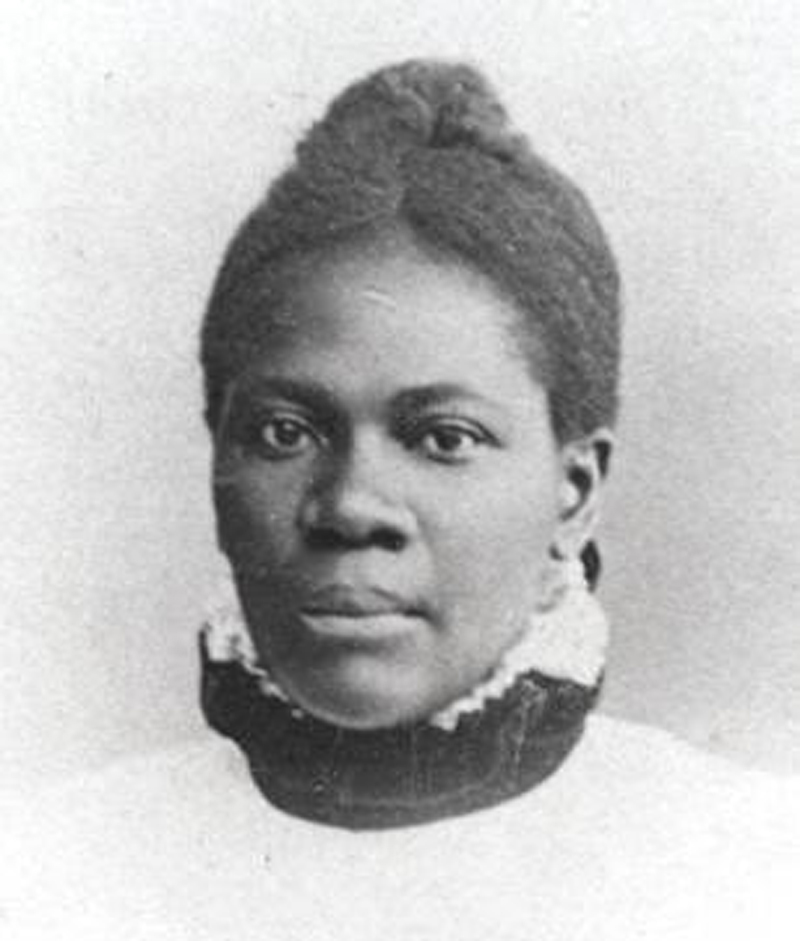

Rebecca Cole

Doctor

March 16, 1846 – August 14, 1922

We must attack the system of overcrowding in the poorer districts … that people may not be crowded together like cattle, while soulless landlords collect 50 percent on their investments.”

A staunch advocate for the poor and for women, Rebecca J. Cole was the second female African American doctor in the United States, who practiced in South Carolina, North Carolina, Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia.

In 1873, she created the Women’s Directory Center, which specialized in legal and medical services for poor women and children, often in their own homes.

Cole’s first hand view of poverty informed her public argument with sociologist W.E.B. DuBois, who argued in his landmark 1899 study, The Philadelphia Negro, that African Americans were dying of consumption because they were ignorant of proper hygiene. Cole accused DuBois of collecting erroneous data from slumlords, and instead argued that high African American mortality rates were the fault of white doctors, who refused to collect complete medical histories of their Black patients.

She also argued her own case, when needed. When working as a representative for the Ladies’ Centennial Committee of Philadelphia, helping to plan the 100th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, she was asked to form a separate Colored Ladies Sub-committee. Cole refused, arguing that Black women should be able to work alongside the rest of the committee, not in a separate group. She won.

Helen Octavia Dickens

Physician / Sexual Health Advocate

February 21, 1909 – December 2, 2001

I sat in the front seat. If other students wanted a good seat, they had to sit beside me. If they didn’t, it was not my concern.”

Helen Octavia Dickens was encouraged by her parents — former slaves — from a young age to focus on her education. She gained admittance to the University of Illinois medical school, and was the only African American student in her class.

After treating impoverished urban areas lacking medical care, Dickens gained a master of science degree from Penn, completed her residency, and was certified by the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

It was in this city that she became the first African American fellow at the American College of Surgeons. She served as a director of the Mercy Douglass Hospital Ob/Gyn Department and also taught at Penn — by 1985 she was named professor emeritus.

Aside from her remarkable achievements, Dr. Dickens was also groundbreaking in her advocacy for sexual health among young women, and led extensive research in teen pregnancy and sexual health issues. She was a medical icon — both in her breaking of racial barriers and women’s reproductive rights.

Crystal Bird Fauset

Politician

June 27, 1894 – March 27, 1965

We should not want to think of America as a ‘melting pot,’ but as a great interracial-laboratory where Americans can really begin to build the thing which the rest of the world feels that they stand for today, and that is real democracy.”

A friend of Eleanor Roosevelt’s, Fauset was the first African American woman elected to a state legislature in the country, chosen in 1938 to represent the 18th District of Philadelphia, which was over 66 percent white.

In that role, she introduced legislation that addressed public health, low-income housing and women’s workplace rights. She later joined Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s “Black Cabinet” to promote African American civil rights.

As a member of the interracial committee for the American Friends Service Committee, she gave over 200 lectures about African American culture to mostly white audiences.

Jessie Redmon Fauset

Writer

April 27, 1884 – April 30, 1961

To be a colored man in America … and enjoy it, you must be greatly daring, greatly stolid, greatly humorous and greatly sensitive. And at all times a philosopher.”

Known as “the midwife” of the Harlem Renaissance, Fauset was an acclaimed writer/editor who used her pen and others’ — including Langston Hughes’s — to further the African American voice in public discourse.

She was the only African American in her graduating class at Philadelphia High School for Girls. Years later, she was an editor for The Crisis, the NAACP magazine started by W.E.B. Dubois.

The most published novelist of the Harlem Renaissance, she wrote four novels, each with a focus on Black culture and the challenges that confronted it.

William Stanley Braithwaite hailed her as “the potential Jane Austen of Negro Literature,” and Deborah E. Mcdowell saw her as a “black woman [who dared] to write — even timidly so — about women taking charge of their own lives and declaring themselves independent of social conventions.”