Philadelphia Forgot A. Leon Higginbotham. America Can’t Afford To

Remembering a judge, mentor, and civil rights icon at a moment the country cries out for him.

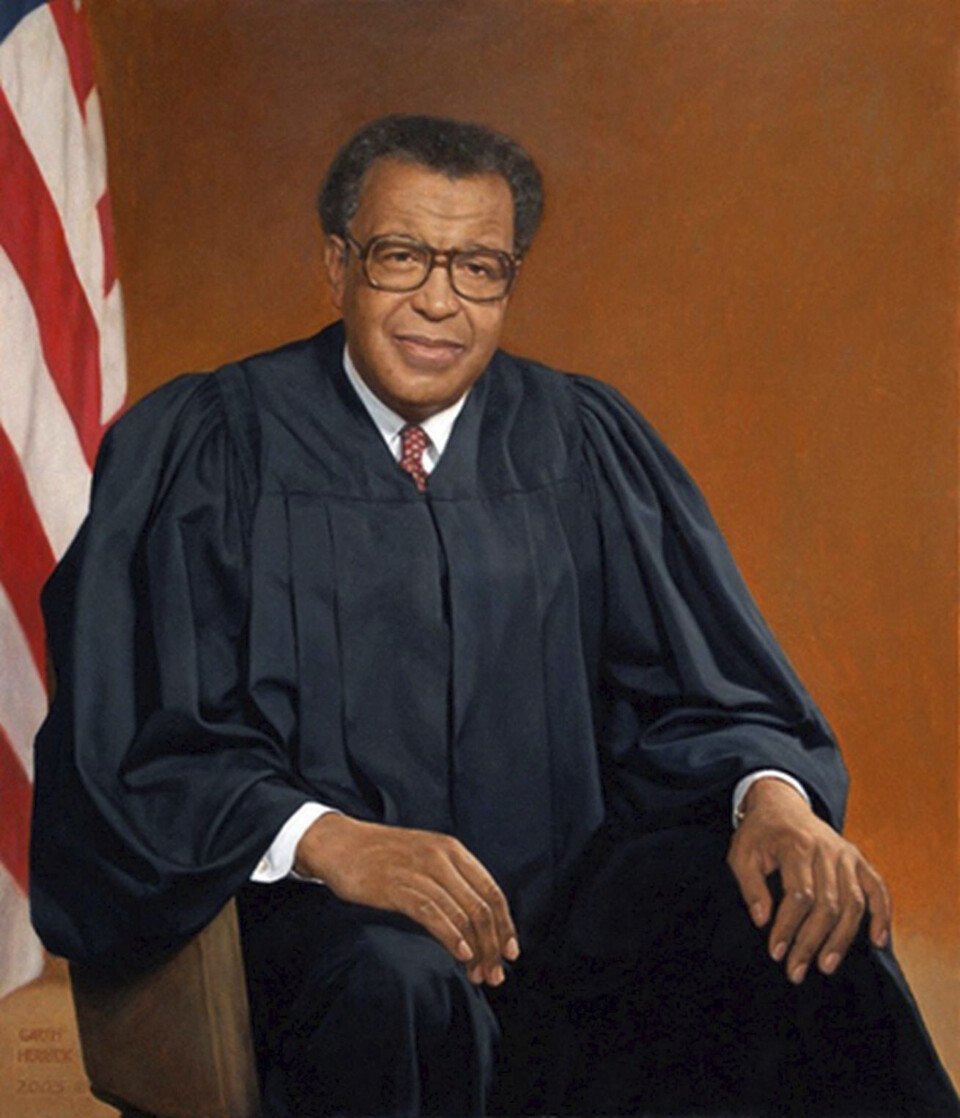

A. Leon Higginbotham / Photograph via Circle Archive/Alamy

The name Aloysius, of Latin origin, means “famous warrior.” And so it was suitable, on December 28, 1998, that a funeral befitting a champion took place. Rosa Parks was there. Nelson Mandela and President Bill Clinton sent tributes; so did Jesse Jackson. Other luminaries lined up to say goodbye to one of the greatest Philadelphians — nay, Americans — of a generation.

Until a few years ago, I had no awareness of Judge Aloyisus Leon Higginbotham, or the impressive life he lived. I’m not alone. His name has been disturbingly lost to history — even in his own city. Winner of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, Higginbotham was a federal judge who just barely missed a seat on the Supreme Court, a trusted adviser to both South Africa’s Mandela and President Lyndon B. Johnson, a trustee of Penn and Yale, and a civil rights pioneer who, almost by sheer force of will and intellect, bent the arc of the moral universe toward justice.

And yet, somehow, for years there were practically no public reminders of Higginbotham in Philly, where he lived and worked for roughly five decades — no statues, no roads, no government buildings bearing his name.

That changed in 2022. After a fundraising effort led by The Philadelphia Citizen (owned by Philadelphia magazine’s parent company, Citizen Media Group), Penn Carey Law School, and Mural Arts Philadelphia, a mural honoring Judge Higginbotham was unveiled at 46th and Chestnut streets. It’s a noble depiction of the legend in his robes, and a towering one too — exactly as so many admirers described him. At six feet, five inches tall, he was “bigger than the Coke machine in the student lounge,” a law school classmate once remarked.

But he was also so much more. When I wrote a story about Higginbotham in the lead-up to the unveiling of the mural, what struck me most were the descriptions of his tenderness, his unflagging mentorship, and even his trademark giggle.

“I think on a certain level, he was self-conscious about [his size],” said Stephanie Franklin-Suber, a former city solicitor and a clerk for Higginbotham in the ’80s. “He was kind. He was compassionate. And he even made an effort to speak to you in kind of a normal tone of voice.”

Aside from her parents, she told me, “he was, is, and always will be the person who has had the greatest influence on my life. Without him, I would be wealthy, but lost.”

Higginbotham refused to tolerate the moral vacuum in politics — a vacuum to which so many others seemed (and seem) resigned. And he was unafraid of a fight. Only a few weeks before his death, he testified in the impeachment trial of President Clinton. There, he dressed down Republican Representative Robert Barr of Georgia, who’d insulted Higginbotham’s expertise: “Sir, my father was a laborer, my mother a domestic. I came up the hard way. Don’t lecture me about the real America.”

In the days since I first wrote about him — especially lately — I’ve mulled over what he would make of today’s morass of ideas about the real America. There is every reason to believe that if he were alive today, Higginbotham would call out the abundance of dismissiveness, cruelty, and ignorance displayed by so many in our government. But even in his absence, the lessons we can take from him are legion.

For one thing, we can borrow from Higginbotham’s radical hopefulness right now. Even as a self-described “survivor of segregation” who faced discrimination at nearly every turn, he was determined to fight for the real values this country stands for. In ways grand and small, he committed himself to the idea that everyone, no matter their station in life, can provide a shoulder on which the next generation can stand. And so much of what’s missing from the world these days — integrity, compassion (especially in a figure of authority), personal sacrifice — was contained in the spirit of this one man, who fought for those ideals to the very end.

After he acquired real power, Higginbotham continued to take moral stances against self-righteous politicians and systemic threats to our civil rights. At a moment when these injustices are more pronounced than at any time since his death, we each need to recapture the former judge’s moral clarity and courageousness to find a way out. If we do, his legacy will live on.

Aloyisus Leon Higginbotham Jr. — he went by A. Leon — was born in Trenton, New Jersey, in 1928. (The unique spelling of his first name was the result of how his father’s was spelled on his own birth certificate.) He attended under-resourced, segregated schools until he enrolled at 16 at Purdue University, where he lived in an unheated attic as one of a dozen Black students on campus.

When Higginbotham confronted Purdue president Edward C. Elliot about the inhumane conditions — at times, the Black students wore three to four layers of clothing to stay warm at night — he was reportedly given an ultimatum: Accept his second-class status or leave the university immediately. Higginbotham promptly left, later citing the incident as the reason he chose to pursue a legal career.

“I knew then I had been touched in a way I had never been touched before, and that one day I would have to return to the most disturbing element in this incident: how a legal system that proclaims ‘equal justice for all’ could simultaneously deny even a semblance of dignity to a 16-year-old boy who had committed no wrong,” Higginbotham told The Legal Intelligencer in 1995.

Higginbotham transferred to Antioch College in Ohio, joining Coretta Scott (yes, that Coretta Scott) as one of only three Black students in the class. He studied sociology there before enrolling at Yale Law School. Although he won a national prize in a prestigious moot court competition, not one of the big law firms in Philly was willing to give him a chance after graduation. Instead, at 25, Higginbotham joined what was later known as “Philadelphia’s first African American firm,” Norris Schmidt Green Harris Higginbotham & Brown.

“I don’t think that there has ever been a better trial lawyer in the city of Philadelphia than Leon Higginbotham,” former federal judge Clifford Scott Green observed in an academic dissertation about the firm. “[He was] just absolutely superb as a trial lawyer, could try anything, criminal, civil, didn’t matter, just absolutely superb.”

Following a career in private practice, Higginbotham spent the next two decades serving in a variety of high-profile positions at the local, state, and federal levels: In 1962, he was appointed to the Federal Trade Commission; in 1963, nominated to the federal bench by JFK; in 1968, following the death of RFK, appointed to the Kerner Commission to investigate the causes of urban riots.

Then, in 1971, Higginbotham — by now a judge — began his involvement in a now-famous case, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Local 542 (International Union of Operating Engineers). The case revolved around 12 Black plaintiffs who accused the union of racial discrimination. When the union pushed to get Higginbotham recused on account of his race, the judge remained steadfast. He stayed on the case for years. As his judicial opinion explained, “To suggest that Black judges should be so disqualified would be analogous to suggesting that the slave masters were right when, during tragic hours for this nation, they argued that only they, but not the slaves, could evaluate the harshness or justness of the system.”

Fierce Warrior, a mural of A. Leon Higginbotham by Shawn Theodore unveiled at 4508 Chestnut Street in 2022. / Photograph by Steve Weinik

Over the course of the next two decades, the judge would make six trips to South Africa, working with Black lawyers there to fight apartheid. When Mandela was released from prison, one of the first people he contacted was Higginbotham, whom he handpicked to advise him on the development of the country’s new constitution.

In addition to his contributions to human rights on a national and international scale, Higginbotham was a dedicated teacher, mentor, and scholar — holding positions at Penn Law, Harvard Law, and Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. He took hundreds of lawyers, particularly young Black lawyers, under his wing to advance diversity in the profession.

“In many respects, he was ahead of his time in terms of DEI,” Tulane University president Michael Fitts told me. (Fitts clerked for Higginbotham in the ’80s.) “He had a very clear vision about diversity and the value to institutions and people.”

For years, Higginbotham was presumed to be on the short list of Democrats’ potential Supreme Court nominees. However, the election of George H.W. Bush closed the door on those dreams. Instead, in 1991, Clarence Thomas was named as the controversial pick to replace Thurgood Marshall, a choice that didn’t sit well with Higginbotham. In the Penn Law Review, he wrote “An Open Letter to Clarence Thomas,” an article that would be republished in newspapers around the country.

Unafraid to rebuke a fellow member of the bench, Higginbotham focused his screed not on the nominee’s politics (or even the sexual assault accusations that plagued his hearings), but instead took aim at his middling qualifications and regressive views on civil rights.

“I wonder whether (and how far) the majority of the Supreme Court will continue to retreat from protecting the rights of the poor, women, the disadvantaged, minorities, and the powerless. And if, tragically, a majority of the Supreme Court continues to retreat, whether you, Justice Thomas, an African American, will be part of that majority,” Higginbotham wrote.

In 1993, the judge retired as a professor at Penn Law and from the federal bench. There was plenty of celebration, but also regret, as voiced by colleagues. “Had President Carter — who appointed Leon Higginbotham to the Third Circuit — been reelected in 1980, or had Walter Mondale won in 1984 or [Michael Dukakis] in 1988, it is a fair surmise that Leon would by now be on the Supreme Court,” wrote renowned federal judge Louis Pollak. “That is where he has long belonged.”

It stands to reason that the course of the Supreme Court, and our country, would have looked different had Higginbotham, instead of Thomas, filled that vacancy.

Maybe it was the country’s loss then, but we need Higginbotham right now, too. If America is to climb out of its current state of moral confusion and division, if we are — to borrow from James Baldwin (as Higginbotham did in his letter to Justice Thomas) — to “make America what America must become,” a study of Higginbotham offers a map. Even in a society that so often treated him poorly in his life (and failed to honor him properly in death), he never strayed from a vision of the country that we all could embrace and live in; he never failed to stand up and insist on that vision. To pay tribute to Higginbotham today is to remember the beacon of hope that he was in his lifetime, yes, but also to see him as a clarion call for all of ours.

Published as “Where Have You Gone, A. Leon Higginbotham?” in the February 2026 issue of Philadelphia magazine.