Meet the Philly-Born Director Changing the Predator Universe

Inside Dan Trachtenberg’s path from working at a video store in Willow Grove Mall to directing one of Hollywood’s biggest sci-fi franchises

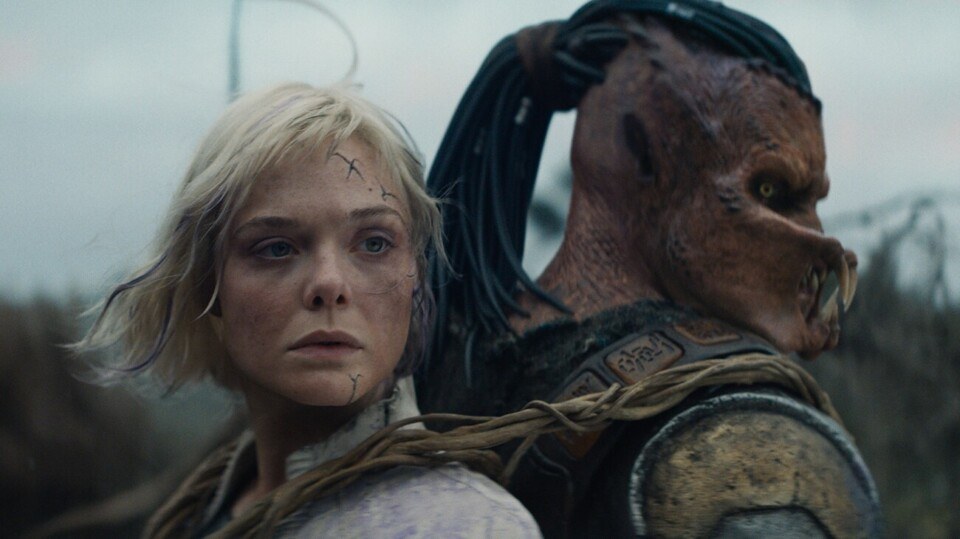

Elle Fanning and Dan Trachtenberg on the set of Predator: Badlands / Photograph by Nicola Dove for 20th Century Studios

Dan Trachtenberg believed he’d made his very own Star Wars. It was 1984, and the three-year-old auteur had recruited his mother to hold the family camcorder while he arranged a lineup of his themed action figures along the kitchen counter. The specific location mattered. A recent behind-the-scenes documentary about George Lucas’s space opera had revealed to him that the saga’s iconic lightsaber hum was inspired by the noise of a refrigerator. “In my kid brain, I thought, ‘Hollywood takes kitchen stuff and turns it into Star Wars,’” he says. “That was all I had to do. Then magic will happen.”

Within earshot of the big appliance’s growl, Trachtenberg lined up his Skywalkers and stormtroopers beside spatulas and ladles, waited for his mom to yell “action,” and then smashed them together to simulate an epic battle. But when he ran back to the screen to witness his stunt, he was quickly disappointed. “He thought he was going to watch the video back and it would be Star Wars,” recalls his older half-brother, David. “But he watched the video back and it was him playing with kitchen utensils.” The result stung, but it would prove to be foundational. Looking back, Trachtenberg says it prompted a question that has since guided his journey from the Philadelphia suburbs to Hollywood: How do you get something to look and feel just as you’d imagined?

Now, as an established 44-year-old filmmaker living in Los Angeles with his wife and eight-year-old daughter, Trachtenberg is still nerding out and chasing that question. The Willow Grove native and Temple alum spent over a decade creating commercials, podcasts, and short films before breaking through with 2016’s 10 Cloverfield Lane, a claustrophobic domestic drama and spin-off of Cloverfield, producer J.J. Abrams’s 2008 monster movie. He parlayed his splashy directorial debut by dabbling in television, but it was his follow-up feature — 2022’s Prey, which premiered on Hulu — that solidified him as a true director to watch, reframing the next iteration of the Predator franchise into an 18th-century survivalist tale. “The stories that I dream up are often taking elements from different genres and putting them together in new ways and creating a new recipe to give audiences an exciting new experience,” he says. Rather than dipping out of the franchise world, Trachtenberg has doubled down. This summer, he co-directed Predator: Killer of Killers, an animated anthology, and this month marks his most ambitious movie to date: Predator: Badlands. Like his entire filmography, the fall blockbuster isn’t a straightforward sequel, but another inventive genre mashup — a sci-fi action buddy flick that follows a Yautja (Dimitrius Schuster-Koloamatangi) and a female synthetic (Elle Fanning) from the apex hunter’s own perspective.

The bold angle, along with what frequent cinematographer Jeff Cutter calls his “muscular filmmaking,” has turned Trachtenberg into the ultimate franchise caretaker, refreshing well-worn IP with a strong sense of place, perspective, and momentum. It’s a designation that can come with intense pressure and a lot of demands — from both rabid fans and risk-averse studio execs. As Fanning tells me, “He’s juggling a lot, but I think what makes him perfect for it is that he’s a fan himself.” Indeed, when we connect over Zoom in mid-August, Trachtenberg doesn’t look stressed at all, though he’s in the midst of reviewing the final VFX touches on Badlands and prepping to meet with a composer to mix the sound (no refrigerators involved this time). “You’re really making the movie feel awesome and feel the way it’s supposed to be feeling,” he says of the process.

After yearning to helm the kind of movies he watched and tried to re-create as a kid, Trachtenberg is now living out a dream — confident that the product he’s putting on screen finally matches the one in his head.

Before Trachtenberg was a budding cinephile, he was a kid learning how to channel his imagination. His parents saw the instincts early, but instead of letting him disappear into movies and TV, they found ways to foster and expand his curiosity. They limited screen time and blocked anything beyond a PG rating, nudging him toward other outlets. The deal, as Trachtenberg recalls, was simple: “I could read anything I wanted that was age-appropriate.”

As a kid at the Meadowbrook School in Abington, he devoured comic books, studied their panels, and then began sketching his own. His mother, Diane, noticed the intensity and hired an art student to teach him how to draw and develop his new passion. He learned anatomy, form, and structure before embracing the looser, more gestural style of cartooning. His dad, Alan, a dentist, fed the obsession in a different way, one day lugging home a wide-screen television, the only one in the neighborhood. On it, Trachtenberg wore out VHS copies of The Karate Kid and Raiders of the Lost Ark, replaying them until their dialogue and mechanics were practically second nature.

By the time he started at Cheltenham High School, his parents had enrolled him in yet another outlet: a Saturday program at the University of the Arts. Trachtenberg took his first real dive into filmmaking there, learning screenwriting and directing while peppering his instructor with questions. In one particular class, he remembers, they were discussing the newly released Starship Troopers when his teacher asked if he’d spotted all of the movie’s fascist imagery. Trachtenberg, the only high schooler in the group, was puzzled. “I was like, what? No, it was just a fun action movie,” he recalls. “And he was like, no, there’s a lot in that!”

That moment stuck. For the first time, Trachtenberg saw that even popcorn fare — specifically, a Paul Verhoeven sci-fi action flick — could carry weight, and that symbols and subtext could elevate spectacle into something richer. At first, he was embarrassed for not having seen it himself, but the embarrassment quickly turned into fuel for his filmmaking aspirations. “I really started reading about mythology,” he says. “I got to understand the symbols that are in the visual texts of everything.”

His interest and excitement led him to other genres and bigger ideas. After renting a copy of John Woo’s Hard Boiled, Trachtenberg fell in love with Hong Kong action cinema — so much that he persuaded his mom to find him a Mandarin tutor. “The idea of becoming a movie director was so daunting,” he says. “I thought maybe my way in was to go to Hong Kong, make movies there, and then bring that back to America.” These were “teenage thoughts,” Trachtenberg says with a laugh, the kind that formed while working behind the counter of Suncoast Motion Picture Company, a retail video store at Willow Grove Mall. Over the summer, he bolstered his film IQ, recommending obscure flicks to customers and meeting up with his girlfriend for lunch in the food court. It was “a real John Hughes-ian high school work thing,” he says.

At the same time, he kept experimenting with cameras. Despite their 12-year age gap, Trachtenberg bonded with his half-brother, David, a film editor living in Los Angeles, who clued him in to the more technical aspects of filmmaking over the phone. Trachtenberg also remembers the day in high school when he realized he could plug one of his camera’s wires into a boombox and create a soundtrack on his student films. “I was starting to really put things together, and my friends were super impressed,” he says. Soon, he was finding excuses to turn academic projects into teacher-approved movies instead. “Everyone else had to do a poster board and had to worry about standing in front of the class,” he says. Not him. As Trachtenberg recalls, his crowning cinematic achievement was a group short film about shigellosis, a bacterial gut infection. “It was a very funny depiction of food poisoning,” he says.

Still, filmmaking didn’t come easy. Trachtenberg had amassed an encyclopedia of influences and ideas, but he knew he didn’t have the instincts of a young Steven Spielberg or M. Night Shyamalan. After getting rejected from film programs at both USC and NYU, he accepted a spot at Temple — but his parents pushed him to keep improving. That summer, they sent him to the New York Film Academy, where Trachtenberg initially felt like “the worst one in the class.” Over the next couple of months, he worked tirelessly, zagging from his classmates’ dense, impenetrable indie-style projects to make something more accessible, with his own comedic sensibility. His final movie project — screened with his mother and sister in attendance — captivated the audience and earned hearty laughs. Afterward, Trachtenberg ran to a pay phone to tell his dad the good news as his mom brushed away tears. “It was a really beautiful moment,” he says, but it was also a realization: “I sort of knew in my bones that if I dedicated every part of my being to doing what I want to do, I could get there.”

Trachtenberg grew up a nerd at just the right time. In 1994, Kevin Smith’s Clerks landed in theaters and showed a group of ordinary slackers dissecting pop culture, comics, and movies with the kind of obsessive energy he’d only seen in video stores and comic shops. It was one of the first realistic glimpses of a subculture that had long felt sidelined. Over the next decade, Smith seized on its success, weaving together his so-called “View Askewniverse” with crossover characters, an animated series, and a kind of mainstream validation for the nerd lifestyle. Long before the MCU turned comic book fandom into the predominant culture, Smith had shown that you could build a career out of your deepest niche interests — and that being unabashedly devoted to them wasn’t something to hide.

As a film student in the early 2000s, Trachtenberg could see his passions and fan culture beginning to influence Hollywood, but he didn’t have a blueprint to follow Smith. Though Temple provided him a good learning ground, “it was very documentary-focused and independent film-focused,” he says, “and not a lot of professors had real set experience the way that I had craved.” Instead of directing, he spent most of his time editing and shooting other classmates’ thesis movies, roles and professions he figured had more discernible career tracks. “I was okay at those things, but there are people that are exceptional,” he says. “It was really frightening to confront that.”

To supplement his schooling, he spent each summer rooming with David in Los Angeles, where he took advantage of more work opportunities. One summer, he spent time as a production assistant; another summer, he worked as a grip and an assistant director on tiny AFI student films. “I would introduce him to a couple of good director friends, and he would pick their brains about how they do things,” David recalls. “I would bring him along anywhere that they would let me.” That included a postproduction editing house, where Trachtenberg recognized the artistry and filmmaking involved in advertising. “Ridley and Tony Scott and Michael Bay and Jonathan Glazer were making these beautiful works of art that were just commercials,” he says. “I realized if I’m going to direct — if I’m going to do the thing that I’m best at — then I just have to make things, and they have to be great.”

When he returned to Philadelphia, Trachtenberg began making his own spec commercials for an ad house in Ardmore. But the opportunities were limited, so after graduating he packed his car and drove back to Los Angeles to find small directing jobs, create more spec ads for various high-profile brands, and start “a multiyear journey of people seeing potential in me,” he says. Trachtenberg still had an immense passion for seeing and discussing movies. David remembers an entire summer when Trachtenberg was living with him when the pair played a word game, matching letters of movie titles by shouting back and forth through the floor and ceiling. “I don’t know if there were any movies left after we were done,” David says.

Predator: Badlands / Image courtesy of 20th Century Studios

Eventually, in 2006, Trachtenberg funneled his immense pop-cultural IQ into Geekdrome, one of the first podcasts devoted to movies, recording reviews with a friend in David’s basement for “tens of people listening.” One of them happened to be Kevin Smith, who eventually emailed Trachtenberg to correct an episode he’d recorded about Clerks. The budding filmmaker couldn’t believe one of his heroes had been listening (or, in retrospect, that he’d introduced an eventually prolific podcaster to the medium itself), and it wasn’t long before he had Smith on as a guest — a pinch-me moment that inspired Trachtenberg to keep chasing his passion.

Over the next couple of years, he gained a bigger audience with The Totally Rad Show, another podcast that netted him more clout in the online world and turned the side hustle into a full-time job. “But as much as I loved communicating about movies and video games and comics, it still wasn’t the thing I was desperate to do,” he says. By then, he’d directed ad spots for major brands like Xbox, Lexus, Coca-Cola, and Uber Eats, but “the commercial stuff was not going to get me there. The thing I had to do was make a little movie to show people I could make the kinds of things I wanted to make.”

In the spring of 2011, Trachtenberg began experimenting with shorts that showed off both his genre instincts and his technical ambition. First came More Than You Can Chew, a five-minute horror story for BlackBoxTV about paramedics stumbling into a house full of corpses, capped with a clever twist. A few months later, he dropped Portal: No Escape, a seven-minute adaptation of the Portal video game that follows a woman breaking out of a sterile prison cell and trying to outrun her captors. The short exploded online — 28 million YouTube views and counting — and instantly put Trachtenberg on Hollywood’s radar.

What made it stand out wasn’t just the clever premise. The short felt like a proof of concept for what would come next: He’d adapted a complex video game, drawn out a compelling lead female performance, stitched in a stylish montage, and used VFX sparingly enough to make its sci-fi world feel tactile. After watching his brother struggle to latch on with commercial work, David could see an emerging visual style and newfound confidence. “He wasn’t just trying to imitate great people,” David says. “He was more interested in saying, ‘How can I take what I’m learning and make something better?’”

His breakthrough started with a Philly connection.

As a student at Temple, Trachtenberg made a short film called Kickin’, a Karate Kid underdog story centered on a soccer player. To pull it off, a friend connected Trachtenberg with Lindsey Weber, a Penn student and budding movie producer, who agreed to help the project by getting extras and background actors to sign waivers. The pair kept in touch over the years. Trachtenberg sent her his commercial reels while she ascended the ranks at Bad Robot, J.J. Abrams’s production company. But it wasn’t until his shorts started attracting buzz that she brought his work to Abrams, who was in need of a director to helm a loose Cloverfield spin-off after Damien Chazelle dropped out to direct Whiplash.

At the time, Trachtenberg had started to make inroads in the industry; he was pitching script ideas and had started talks to direct a comic book adaptation of Y: The Last Man. Though the project was still in development, it gave him credibility and leverage with Abrams, who thought Trachtenberg’s short films and vision perfectly aligned with his script about a woman who survives a car accident and wakes up inside a bunker with two strange men, waiting out an alleged massive chemical attack. “The initial idea was to maybe build a little set and just shoot it in the office at Bad Robot,” Trachtenberg says. “And then it kind of blossomed into something a little bit bigger.”

With a loaded title like 10 Cloverfield Lane and a cast featuring John Goodman, Trachtenberg was suddenly thrust into the spotlight and given the keys to forge a new direction for a fan-favorite monster franchise. At first, the opportunity seemed daunting. “I’m quite introverted. Especially in big groups,” he admits. But as he began preproduction, meeting with department heads and discussing story beats with actors, he’d never felt more comfortable, finally surrounded by people who cared as much as he did. “I’m in giant meeting rooms with a bunch of grown men and women taking make-believe very seriously,” he says. “There’s always a moment where an argument might happen between two departments trying to figure out how to do something best. And I get really emotional.”

For most of its runtime, 10 Cloverfield Lane doesn’t feel burdened by its predecessor. It’s a taut, claustrophobic test of wills, and Trachtenberg augments the tension with close-ups, tilted angles, and framing devices that inhabit his trio’s temperamental headspace. According to cinematographer Jeff Cutter, Trachtenberg’s overarching goal was to film the bunker scenes with still, solid movement, switching to more jittery handheld lenses aboveground once his female protagonist escapes her prison. “There’s a real drama to the way he stages and blocks things, a tension to where characters sit in frames and where the camera is in relation to those characters,” Cutter says. “With freedom comes uncertainty of what is actually out there — so the handheld then really reflected that sort of quality.”

The movie quickly turned into a hit, earning $110 million at the global box office (against a $15 million budget) and nearly unanimous favorable reviews. Its success was a huge relief for Trachtenberg, who didn’t want his debut to be “the story of this guy who was given this opportunity and it’s terrible,” he says. At the same time, he couldn’t help but look ahead. “It’s like, okay, but now what? I’ve got to do this again. And if the next one’s bad, that’s it for me,” he says. “It’s hard to let that validation keep wind in the sails for future choices that you have yet to make, because you can see people stumble so often.”

In the direct aftermath, however, Trachtenberg didn’t immediately pounce on movie opportunities. Instead, he honed his skills and dipped his toe into television, directing an episode of Black Mirror and then teaming up with writer Eric Kripke to helm the first episode of The Boys. Maybe it was a risk not to ride Cloverfield’s momentum and jump into a Star Wars or big franchise opportunity (like older peers Gareth Edwards and Colin Trevorrow had), but Trachtenberg resisted the temptation and kept his focus on developing his voice and writing his own projects. “That’s what I was passionate about,” he says. “If I was ever going to make a franchise movie, I wanted to be in a place where I wasn’t making the movie that the studio wanted to make, but the movie I wanted to do.”

One of Trachtenberg’s earliest original ideas was Crime of the Century, billed as “a high-octane heist with a science fiction twist.” Fast and Furious producer Chris Morgan enlisted him to direct it for Universal back in 2011, but the project languished in development. After another stalled attempt to get it off the ground, however, Trachtenberg shifted course and reconsidered his path forward. If the industry wasn’t biting on his personal pitches, even after his debut success, maybe the solution was to take another piece of well-known IP and Trojan-horse his imagination inside it. He had had success with 10 Cloverfield Lane. Why not try again?

As he considered his next move, Trachtenberg thought back to a movie that had left an indelible mark on him: Predator. On the surface, it felt like an odd fit, maybe even ironic — finding creative freedom inside a decades-old monster franchise. But for Trachtenberg, it was the perfect canvas. When he was a kid, the original Arnold Schwarzenegger flick had delivered the visceral thrills of action, horror, and sci-fi unlike anything he’d experienced before. He already wanted to tell a cross-genre story set centuries in the past. What he needed was a worthy antagonist. The Predator, it turned out, was the perfect monster to make those ambitions real.

After weathering pandemic delays and the complications of Disney’s Fox acquisition, Trachtenberg finally brought Prey to life. He reimagined the franchise in the early 18th century, centering the narrative on a young Comanche woman learning to hunt, and in the process expanded the Predator’s legacy far beyond its usual blueprint. Released on Hulu, Prey became the streamer’s biggest premiere ever (among both film and TV shows), received strong reviews for its grounded storytelling, and earned Trachtenberg two Emmy nominations. “Dan is interested in finding stories with heart, but with unexpected takes on them,” producer Ben Rosenblatt says. “He has no interest in rehashing what’s been done. And in the Predator franchise, rehashing what’s been done can be a trap.”

Entrenched in the world with an engaged new fan base, Trachtenberg kept using his innovative thinking to expand the Predator universe. That started with June’s Predator: Killer of Killers, which he co-directed with Micho Rutare, weaving three separate animated stories from different time periods together. The pivot let him engage his love for martial arts movies with the flexibility of illustration. “I was allowed to unleash and apply a lot of those initial theories that I learned drawing comic books,” he says. But this month, he’s leveled up even more. With Predator: Badlands, Trachtenberg pushes the franchise further into new territory, adopting the perspective of a Predator protagonist alongside a legless synthetic companion while reintegrating the Alien universe. “I think sometimes we get a really cool original movie and then the sequel is just part two of the cool thing and not a cool thing in and of itself,” he says. “I started thinking about: How can we root for the Predator? How can we root for the monster?”

Thia (Elle Fanning) and Dek (Dimitrius Schuster-Koloamatangi) in Predator: Badlands / Image courtesy of 20th Century Studios

Trachtenberg shot the entire movie (which David edited, marking their first feature collaboration) on location in New Zealand, building as many practical sets and stunts as possible. That meant thinking creatively about how to capture Fanning’s immobile humanoid getting thrown over a Yautja like a backpack. For VFX purposes, he covered her legs in blue, but Trachtenberg also relied on Fanning to try things physically, with wheelbarrow devices or Texas switches with stunt doubles. “He just loves the magic of moviemaking and the little tricks that you can accomplish,” Fanning says. “When you have someone at the helm who is so excited by those things, it just keeps everyone’s energy up and alive and reminds everyone that we’re doing something fun and it’s a privilege to be there.”

It’s one of many reasons why Trachtenberg has become the franchise’s reliable leader. He cares about this stuff and has remained curious about it. “You meet a lot of people in the industry and they’re talking about themselves, talking about what they think, feel — they’re very self-centered,” Rosenblatt says. “Dan’s the opposite. When you meet him, he’s asking about you. He wants to know what you do and how you do what you do.” Trachtenberg is also grateful. Earlier this year, he ran into Smith at Comic-Con’s Hall H, and the pair shared a “treasured moment” together reflecting on their first encounter. He also brought his parents out to the Badlands premiere to celebrate with him and David, another small thank-you for their commitment to his arts education. “To see how far he’s come and what he’s done, and then to get to work with him,” David says, “it’s pretty mind-blowing.”

Trachtenberg doesn’t quite know what’s next. He’s already directed an episode for the latest season of Stranger Things and has more ideas for Predator — but after spending so much time playing in other worlds, he’s itching to resurrect a couple of his paused projects and build his own. In the meantime, he’s still happy to smash toys together. Fanning saw it firsthand. She remembers Trachtenberg’s giddiness over the Predator’s weapon collection — rifles with custom clips, magnets, even switches designed for cinematic flair — and plotting camera angles and scene ideas, much like he did on his kitchen counter in Willow Grove. “He was just like, ‘We’ve got to shoot it this way. Look how cool it is,’” she recalls. “No one nerded out more than Dan.”

Published as “Hit Man” in the November 2025 issue of Philadelphia magazine.