Sneak Peek: Larry Magid’s New Book About the Best of Philly Music

Philly’s real soundtrack is bigger, louder, weirder, and impossible to pin to one hit. In a new anthology, music impresario Larry Magid gathers the musicians, mischief-makers, and scene-builders who scored a city that never stops remixing itself.

Back in 1974, Philly composers Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff wrote “TSOP (The Sound of Philadelphia),” the irresistibly catchy theme song for the TV show Soul Train. Its funky strings, bold horns, thumping bass, and cheeky lyrics (“Let’s get it on; it’s time to get down”) catapulted the song to No. 1 on The Billboard Hot 100, making it the first TV theme song ever to hold the spot.

The following year, “TSOP” nabbed a well-deserved Grammy for Gamble and Huff, a spectacular moment of pride for the hometown duo — yet too small of a recognition for the actual sound of Philadelphia, which is actually impossible to contain in a single song.

It’s more like a crazy, multi-movement symphony: big, unruly, and ever-evolving as the city itself.

The Philadelphia Music Book: Sounds of a City, a new anthology edited by Larry Magid, attempts to capture all of it. Not just the artists who have contributed to its wild cacophony but the people, places, and cultural moments that have added weight, form, reference, and context to the soundtrack we move to.

Magid, of course, is the 82-year-old, West Philly-born rock-and-roll impresario, co-founder of the Electric Factory, producer of Live Aid, steward of the Philadelphia Music Alliance, and all-around amplifier of the city’s musical lineage. In Sounds of a City, he has commissioned from more than a dozen contributors and journalists (including Philadelphia magazine’s own Larry Platt) biographies of its best-known musicians, historians, critics, DJs, and scene-makers into one generous love letter to a town that refuses to stay in a single genre — or sing in the same key.

“It’s all music, and altogether it makes up the rhythm of a city,” Magid says in Sounds of the City. “Whether it’s an Eagles game and you’re singing the Eagles fight song, or it’s the Gamble and Huff songbook, it brings everybody together and you feel the pride in the city. From the Philadelphia Orchestra to Bill Haley to Bandstand and the ‘Philly Sound’ — these things changed people’s lives.”

Here, a few of the musical characters that have contributed to the symphony, excerpted from Magid’s brand-new The Philadelphia Music Book: Sounds of a City, with the permission of Camino Books.

Eugene Ormandy, 1899-1985

Eugene Ormandy / Photograph by Neil Benson, courtesy of the Atwater Kent Collection, Drexel University

After a Philadelphia Orchestra concert at Carnegie Hall in fall 1952, the New York Herald Tribune ran what remains one of the all-time great raves: “The Philadelphia Orchestra, believe it or not, is a better orchestra than it used to be. It is even better, I think, than any other orchestra has ever been,” wrote music critic Virgil Thomson. He went on to ascribe credit: “Eugene Ormandy has achieved the seemingly unachievable.”

Ormandy at that point had led the orchestra for 16 years, and his chance for success after the idiosyncratic, spotlight-adoring Leopold Stokowski was far from guaranteed. But he made their sound his own — and not just because he was at the helm for an astonishing 44 years. His great achievement was homogeneity — a blended, quite powerful overall orchestral sound so magnificent it made even less-than-first-rate music sound beautiful.

Born in Budapest as Jenő Blau, Ormandy started his career as a violinist. He came to the U.S. in 1921 and played in the orchestra of New York’s Capitol Theater. Before one show, the scheduled conductor fell ill. Ormandy filled in and was named associate conductor. He was noticed in another concert by manager Arthur Judson, who booked the young conductor on radio shows and at orchestra summer venues — including one in Fairmount Park. He led the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra for five years before being tapped by Philadelphia in 1936.

Ormandy gave audiences what they wanted: Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff, Sibelius, and showpieces — plus important premieres and American works—and the orchestra recorded prodigiously. Broadcasts, tours, and recordings fixed in the ears of millions the way certain pieces should sound — the inexorable power of the Saint-Saëns “Organ” Symphony and the green lush and sparkle of Respighi’s tone poems. This sonic imprint had a name — and an author willing to take credit for it. “The Philadelphia Orchestra sound,” Ormandy once said in a New York Times interview — “it’s me!” — Peter Dobrin

Nina Simone, 1933-2003

Nina Simone / Image via Amazing Nina Documentary Film, LLC

Nina Simone was and remains an iconic figure in American music and culture. Outstanding as a singer, songwriter, and pianist, her eclectic embrace of jazz, folk, gospel, blues, Broadway, and classical music transcended conventional boundaries, while her conscience demanded she sing out about racial injustice as few other artists of her time dared, with pungent originals including “Mississippi Goddam,” “Four Women,” and the anthemic “To Be Young, Gifted and Black.”

Born Eunice Kathleen Waymon, this child prodigy first aspired to a career as a classical pianist, confidently relocated with her family from North Carolina to Philadelphia to attend the Curtis Institute of Music, and then did not pass the audition. She blamed the rejection on prejudice (Curtis presented the artist with a belated honorary degree shortly before her demise). But two Curtis faculty notables — Vladimir Sokoloff and Harold Boatrite — took her on as a private student. Sokoloff famously suggested she do something with that jazz noodling he had heard.

Simone took a piano-playing gig in 1954 at the Midtown Bar and Grill in Atlantic City — the first time she used her stage name, to hide the job from her mom. At the club manager’s insistence, she reluctantly started singing too, in a richly soulful, mahogany-toned voice that turned heads and eventually led to a contract with Bethlehem Records and her first album release, Little Girl Blue, in 1958.

Back in Philly, another admirer then put her over the top. WHAT-FM jazz DJ Sid Mark jumped on Simone’s tremendously touching take of “I Loves You, Porgy,” sometimes spinning it twice in a row “to wake up the suits at Bethlehem that they were sleeping on a smash” as he told the Philadelphia Daily News. In 1959, the rendering became a national R&B hit and sold over a million copies. Thirty years later, another track from the same album, “My Baby Just Cares for Me,” likewise took off internationally, after being featured in a Chanel perfume ad.

Prolifically recording over the next few decades for multiple labels, Simone also built a boundary-free following with distinctive covers of “I Put a Spell on You,” “Feeling Good,” and “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood.” After the 1968 death of Martin Luther King, Jr. — with whom she had marched in Selma, Alabama — Simone wrote and recorded the painful “Why? (The King of Love Is Dead).” And she essentially washed her hands of America, taking exile in Liberia, Switzerland, France, Trinidad, and elsewhere, though periodically returning to record and perform.

Sometimes dismissed as a difficult diva, Simone’s personal life was marked by turmoil and challenges. She faced racism, experienced financial difficulties, and struggled with mental-health issues. Today, Nina Simone’s art is just as riveting and even more popular than it was in her lifetime. Her influence lives on in the conscious music and activism of many disciples, among them Lauryn Hill, Beyoncé, Alicia Keys, and John Legend. — Jonathan Takiff

Kevin Eubanks, b. 1957

Kevin Eubanks / Photograph by Oliver Abels

For Kevin Eubanks, music transcends life, taking you on an unimaginable carpet ride if you don’t take things too seriously. He grew up in North Philly and described “all the time” access to music, hitting tambourines and bass drums in his grandmother’s church with his older brother Robin, and having two jazz musician uncles close by — Ray and Tommy Bryant. Yet his mother, Vera, a classically trained gospel pianist, was his primary educator. Eubanks loved funk and recalls the seminal impact of seeing James Brown perform at the Uptown Theater. Afterward, while he and his brother were standing by the curb waiting for their father to pick them up, he decided that he did not want to dance, sing, or try to be James Brown, but only “to play guitar.”

A local bar, the Chatterbox at 24th and York, asked Eubanks to play there. He thought, I can’t play in a bar, I’m only 15, and my dad is a gold-shield detective. He was surprised when his mother convinced his father to approve the gig, with supervision. She knew he needed to perform to become a successful musician. In his Germantown High School days, every neighborhood had a band with a hip name — Breakwater, Black Gold, Pitch-black, and Eubanks’ band, Sundown. Battle of the Bands was the place where funk musicians jammed and competed. Having an instrument also earned access to rival gang neighborhoods.

After leaving Philly, Eubanks graduated from Berklee College of Music and performed with Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers with Wynton and Branford Marsalis. The latter hired Eubanks to join him on the Tonight Show with Jay Leno in 1992. A highly publicized blowout between Leno and Marsalis allowed Eubanks to become musical director in 1995.

Kevin Eubanks’ smile, laugh, and easygoing nature allowed him to co-star with Leno on the Tonight Show, the Jay Leno Show, and currently You Bet Your Life on the FOX network. — Brent White

Solomon Burke, 1940-2010

Solomon Burke in Billboard, 1967

Born in the Black Bottom neighborhood of West Philadelphia, soul singer Burke’s mother was a nurse, teacher, and pastor; his and stepfather, a rabbi. He was born to perform, hosting a radio show on WHAT-AM as a teenager while traveling to revival meetings on weekends.

Burke recorded for the gospel label Apollo in the 1950s, starting with his self-penned song “Christmas Presents.” Like Sam Cooke and Wilson Pickett, he hit his stride when crossing over to the secular realm. He made that move with two singles on Philadelphia label Singular Records in 1959, and the next year inked a deal with Atlantic with Jerry Wexler, who later called him “the greatest male soul singer of all time.” Burke’s R&B hits at Atlantic were profoundly influential: “Just Out of Reach (of My Two Open Arms)” and “I Really Don’t Want to Know” found common ground between soul and country. The blues-based numbers “Everybody Needs Somebody to Love” and “Cry to Me” were recorded by the Rolling Stones, and the latter song turned up in the 1987 film Dirty Dancing.

Burke was always one of soul music’s most compelling characters. For years, he ran his own mortuary business in Los Angeles for many years. And his family was huge: he had 21 children and 90 grandchildren. “I got lost on the Bible verse that said, ‘Be fruitful and multiply,’” he said. “I didn’t read no further.” A career resurgence began with his 2002 album Don’t Give Up on Me, with new songs written by Bob Dylan, Dan Penn, Tom Waits, and producer Joe Henry. It won a Grammy and put Burke back in the public eye – and acknowledged his rightful place in history. In the end, he had to be brought to his throne in a wheelchair but still carried himself like royalty. — Dan DeLuca

Lisa “Left Eye” Lopes, 1971-2002

Born in Philadelphia, Lisa “Left Eye” Lopes was a fiery soprano rapper, singer, and songwriter. She got her nickname when an admirer noticed her asymmetrical eyes and stated the left one was bigger and therefore prettier than the right. She was the most flamboyant and creative member of TLC, one of the biggest girl groups of all time. Formed in Atlanta in 1991, the name was created from the first initials of the group’s best-known lineup: Tionne “T-Boz” Watkins, Left Eye, and Rozonda “Chilli” Thompson. With their feisty anthems of women’s empowerment, TLC was part of the new jill swing era, which featured female performers doing a combination of hip hop and contemporary dance beats. Their songs also addressed serious subjects including drug abuse and safe sex.

Their 1992 debut album, Ooooooohhh… On the TLC Tip, was a critical and commercial success, selling four million copies in the U.S., with three top-ten singles. CrazySexyCool, their 1994 release, spent seven weeks at the top of Billboard’s charts and contained their biggest hit, “Waterfalls.” It sold 11 million copies. The video for “Waterfalls” made TLC the first Black act to win an MTV Video Music Award. Despite their worldwide success, TLC filed for bankruptcy in 1995, citing a highly unfavorable deal with their management. Nevertheless, FanMail debuted at number one on the charts in 1999 and sold 10 million copies worldwide. Together TLC sold over 65 million records worldwide, making them the best-selling “girl” recording group since the Supremes.

The life of Lisa Lopes was marked with as many headlines as hits. A harsh childhood left scars. By 1994 she was in a turbulent relationship with Andre Rison, a wide receiver for the Atlanta Falcons. After a fight, she set fire to his basketball shoes in a bathtub and accidentally burned down his house. She was fined and placed on probation, and their relationship continued. Although Lopes seemed to be a lighthearted, outrageous, even goofy human, she also had a deeply spiritual side. This was evident in her final production, a documentary for VH1 filmed over a 27-day spiritual retreat. It was ultimately titled The Last Days of Left Eye. At age 30, with so much of her life before her, Lopes died in an auto accident. — Juli Vitello

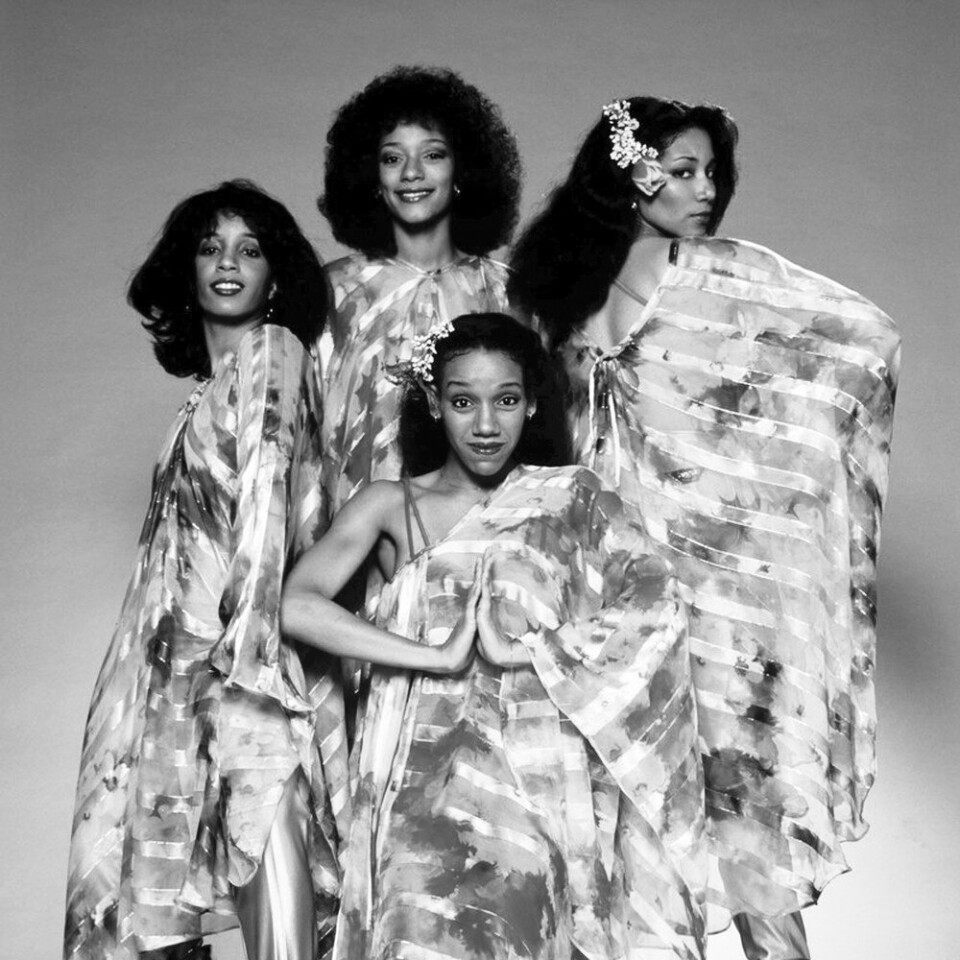

Sister Sledge

Sister Sledge / Photograph by Gijsbert Hanekroot / Redferns

Siblings Debbie, Joni, Kim, and Kathy Sledge are the daughters of tap dancer Edwin and actress Florez Sledge and the granddaughters of opera singer Viola Williams. First billed as “Mrs. Williams’s Grandchildren,” the sisters got their start singing at Williams Temple CME Church in South Philadelphia. Their initial commercial release came in 1971, and their first dance club hit arrived in 1974 with “Love Don’t You Go Through No Changes on Me.” That year, the sisters were featured in Zaire 74, the all-star concert in Africa that included performances from James Brown and Miriam Makeba. And they are featured in the 2009 concert film Soul Power.

Their Circle of Love debut was released in 1975, when they were still teenagers. Neither that album nor 1977’s Together was successful, but the group hit pay dirt two years later. We Are Family, the album, was written and produced by Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards of Chic. It turned Sister Sledge into international stars. Along with Gloria Gaynor’s “I Will Survive,” the song “We Are Family” is the most enduring empowerment anthem of the disco era. “Recording it was like a one-take party — we were just dancing and playing around and hanging out in the studio,” Joni said in a Philadelphia Inquirer interview. The song has been covered by the Spice Girls, the Corrs, Babes in Toyland, and characters from The Muppet Show. The album’s “He’s The Greatest Dancer” and “Lost in Music” were also hits, with the former sampled in Will Smith’s “Gettin’ Jiggy Wit It.”

Sister Sledge has continued to perform, in various configurations, in the decades since their disco-era commercial peak. Kathy went solo in 1989, scoring a dance club hit in 1992 with “Take Me Back to Love Again.” She did not join her sisters when they preceded Pope Francis onstage at the 2015 World Meeting of Families in Philadelphia. Joni died in 2017, but Debbie and Kim continue to perform as Sister Sledge. — Dan DeLuca

The Philadelphia Music Book: Sounds of a City is a collaboration between Camino Books and the Philadelphia Music Alliance, and royalties from sales of the book supports the Philadelphia Music Alliance. Established in 1986, the Philadelphia Music Alliance is a community-based, not-for-profit organization dedicated to preserving and promoting Philadelphia’s rich musical legacy by increasing awareness of the city’s great musical tradition and supporting the current music scene. To order a copy of Sounds of a City, click here.