Inside Pennsbury High’s Legendary Prom: The Most Epic School Dance in America

A six-figure budget. Hundreds of helpers. Giant art installations. A tentacled kraken. This prom is like no other.

Pennsbury High School Prom / Photography by Dina Litovsky

There’s a boat in the lobby of the high school. It’s not a real boat, of course; it’s a 16-foot replica made of Styrofoam. The boat is grounded now, ashore on the shiny tile floor, upside down, protected by a barricade lest students knock into it and crack its delicate hull.

It would be weird, a boat in a school, but this is Pennsbury High School in the middle of spring, which means one thing.

Prom.

When it comes to public high schools in America, Pennsbury, a two-building campus that sprawls over 44 acres in Bucks County, is pretty ordinary — a school you could copy and paste into any middle-class suburb. There’s the auditorium, where the ninth-grade band recently played a medley of sea shanties. There’s the gym — one of three — where this year’s district-title-winning boys volleyball team played. There’s the football field, where this past June, 759 students graduated, a sea of white caps bobbing in 88-degree heat as Governor Josh Shapiro delivered the commencement address. The ceremony unfolded as most graduation ceremonies do: neatly rolled diplomas deposited in hands, caps tossed triumphantly in the air, cheers and tears, an end and a beginning all at once.

Inside the school, there are the quintessential skinny rows of lockers dented from years of abuse, drab laminate cafeteria tables, drop ceilings with bad fluorescent lighting, cinder-block walls taped with all the reminders that go along with life in high school: Spirit Day, Sports Nite, art shows, marching band tryouts, SATs.

But then there’s this, a poster taped to the door of teacher Maggie Weber’s art room: “We Need YOU to help make the Best Prom in America.”

If that declaration seems grandiose, consider this: The Pennsbury prom has been in existence in some form since the first class graduated in 1949. Instead of renting out the typical catering hall or wedding venue, the school hosts its prom on campus. Hundreds of students, teachers, parents, and community members work for months to transform the place with elaborate decorations and art. A thousand or so people arrive on the morning of every prom for a tour.

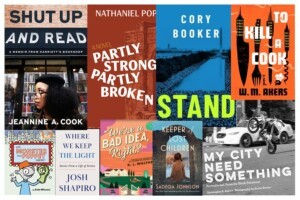

They’ve had celebrity performers — John Mayer, Questlove, the Sugarhill Gang — paid for out of a six-figure budget. There’s a parade, with hundreds of visitors watching prom-goers make grand entrances on handmade floats — or, as in years past, in fire trucks, ice-cream trucks, boats, antique cars, Batmobiles, helicopters (now banned), and on horses (also banned). There’s a red carpet and a hypnotist. The prom has been covered by Vice, Rolling Stone, and USA Today. Somebody wrote a book about it.

And anyway, Pennsbury didn’t come up with the distinction itself. It was bestowed on the school in 2004 by Reader’s Digest.

But this isn’t a story about a prom, not entirely. This is a story about how a community comes together to turn an average American high school into a place of magic. It’s a monumental effort, one that takes a small army to pull off. I sit with Maggie, one of the high school’s six art teachers, in her classroom one evening in mid-April as she sketches out the “prom hierarchy.” There are four faculty advisers who oversee the day-to-day work, plus two assistant principals who get involved with larger managerial aspects. (“They help get shit done,” Maggie says, before catching herself for cursing.) There are 62 prom chairs, plus 11 “Prom Com” student groups (about 250 kids total) and four parent groups, each with 15 to 30 volunteers; dozens more pitch in for the final weeks. She ticks off names — Lindsay Gebeau, a gym teacher; Amanda Durham, an English teacher; Dan Mahoney, visual production; Laura Tittle, assistant principal; Mark, the head of the 3-D decor parent group; Jess, one of the student prom leads.

But the names all slide together, and I’m having trouble focusing on her flowchart because Maggie’s classroom is a riotous art studio bursting with color, and there’s just too much to see. Art is all around us — over the ceiling, on the doors, covering every square inch of the walls. There are supplies scattered everywhere, haphazard stacks of paper, a sink exploding with paintbrushes, shelves of paint, a ladder, paper garlands, fake flowers, a few mannequins. Administration is nagging her to clean it up, but Maggie seems undisturbed by the chaos, as are her students. Honestly, the mess is less distracting than the sound I’m hearing, a faint scratching that seems to be coming from the ceiling.

“Oh, that’s Skittles,” Maggie says, still undisturbed. “Our resident squirrel.”

Maggie, now in her eighth year at Pennsbury, can’t really be blamed for the state of her art room. The building she’s in, Pennsbury East, is 60 years old and desperately lacks storage — for art supplies, for books, for technology, and for decades of prom paraphernalia, like a huge Styrofoam replica of the famous statue of David (only the head is here, as the full statue was 20 feet tall), a giant papier-mâché elephant head, a carved Styrofoam statue of the Buddhist bodhisattva Guanyin, fake brick walls, a big anchor.

“It’s just everywhere — in janitor’s closets, in secret hiding places. In all the crevices of the school are remnants of proms past and present,” says Maggie. This storage problem is why the boat is in the lobby, why mural rolls are stashed on top of lockers — and why Pennsbury is embarking on a nearly $270 million project to tear down both buildings and build a new 497,000-square-foot high school. Of course, the prom isn’t the driving force behind the plans, but it did inform them. “This is arguably our biggest event of the year. We need to make sure we’re giving it the resources and support it needs,” says PHS principal Reggie Meadows.

Before long, kids start to trickle into Maggie’s classroom, and her flowchart is scrapped. She promises to email it to me. She tucks her pencil into the messy bun on top of her head, smooths her long floral skirt, adjusts her art apron. It’s time, she tells me, for Paint Night.

“Just wait,” she says. “It’s gonna get crazy.”

Six Weeks Before Prom

“No water guns in this room! Hard line!” Amanda Durham yells across the gym. We’re in the high school’s East building, where the prom is held — this year on Saturday, May 31st. All prep work happens here too, including the painting of more than 240 large-scale murals that will eventually be hung throughout most of the building’s first floor. Right now, nine of them are spread out on the gym floor in varying stages of completion. Amanda points to one.

“This is tempera paint! Water will ruin these murals,” she warns. For weeks, the senior class has been playing a popular high school water-tag game, but now the students, most wearing goggles, sheepishly put away their water guns and pick up their paintbrushes. They’re here for Paint Night, and it’s time to get to work.

These Paint Nights started out weekly in mid-March; they’re now held twice a week or more, on evenings when the gym isn’t needed for sports. The whole mural process is a fairly well-oiled machine; kids have been mural-ing the school for prom since at least 1969. It works like this: Each prom group is assigned an area of the school to decorate based on the prom’s central theme — this year it’s mythology — and each area has a specific number of murals needed to cover it, generally between four and 13. They used to tape paper together to get it big enough — some of the murals span 100 feet — but now they use professional mural paper that’s bigger and fire-retardant (and expensive; this year, Maggie’s paper order was more than $8,000).

As the evening winds on, kids grab more murals, some weighing 20 pounds, carrying them on their shoulders like giant logs. When students run out of room in the gym, they work in the hallways, and when they run out of room there, they work outside. They mix their paints in random containers: “grass green” in an empty gelato jar, “leaves” in an empty cat-food tub.

I understand why kids join Prom Com. It’s fun being in the school after hours, shuffling around in socks (no dirty shoes near the art!), listening to music, painting alongside your friends. It’s relaxing, almost meditative. And then, around 7:30, things begin to unravel. It starts when two girls run up to Amanda.

“Mrs. Durham, we made an oopsie,” says the girl with goggles on her forehead. “We painted green where it’s supposed to be water.” Amanda walks over to the mural, a 35-foot-long depiction of the story of Echo and Narcissus, and sees that there is indeed green where there should be blue.

“This is fixable,” she says calmly, kneeling to assess the damage. She offers a few suggestions: They could try to wipe off the paint. They could attempt to make it appear as a reflection in the water. Or they could simply go over it with white paint and start again. Worse things have happened. Amanda leaves to attend to another group, and the girls stare at their mural for a long while.

“We’ll figure it out,” the girl with the goggles finally says.

Another student speeds by: Jess, one of the prom chairs. “Where is white paint?” she asks frantically. (Maggie told me about the white paint. They always end up running out of it — she did an emergency order of 15 gallons last week and hid it in her classroom.) And then Maggie races by, waving me along.

“They’re seeing if Medusa’s head fits,” she says, as if this is something that happens often in this gym. I run to catch up, sure I’ve misunderstood, but a man in a T-shirt from last year’s prom (they sell prom merch) is standing over a massive wooden structure in the vague shape of a head. Another man holds two large eyeballs — plasma globes set in Styrofoam spheres that will be mechanized so they move around in the wooden sockets.

“I think it looks good,” announces the man in the old prom T-shirt. This is Mark Sanford, a software engineer and the leader of the 3-D group that handles animatronics. (Maggie calls them the Prom Dads.) This year, the group is working on four major projects: the head, which will be the 3-D centerpiece of a large mural; a centaur; a phoenix that will rise nine feet in the air and spread its wings; and a dragon that will fly back and forth across the gym on a track in the ceiling. Well, that’s the plan, anyway. The 3-D group has been trying to get the track working for years. They almost succeeded last year, but something went wrong at the last minute, and in the end, the huge narwhal that was supposed to sail dramatically across the gym was simply hung in the middle of the room. It’s still a very sensitive subject.

“The challenge is making it all from scratch, and on a shoestring budget,” Mark says. Turns out that six-figure budget — which principal Reggie Meadows says is generated from ticket sales (they cost $140 each), sponsorships, donations, and community fundraisers — dwindles pretty quickly, especially when you have to feed more than 950 kids and pay for nationally known entertainers.

But, says Mark, “I love the challenge. And I’ve always said that the biggest aspect of this is the people behind it.” They’ve become friends, the 3-D group, keeping in touch all year via a WhatsApp text chain to discuss prom plans.

Mark’s wife asks him every year why he’s still doing it. She’s not against the prom, but he’s 63 now, and it is a lot of work and a huge time commitment.

Oh, and their youngest graduated from Pennsbury 13 years ago.

Four Weeks Before Prom

The Prom Dads are in the wrestling room, contemplating a giant headless horse. The horse had a head back in 2013, at the “Through the Decades” prom. (It was part of the “Western 1890s” section.) Since then, the creature — the body alone is five feet tall, made of pipes, chicken wire, papier-mâché, and cement — has been living in a shed in George Mershon’s back yard. George had grand plans to open a fire museum one day, and he figured the horse would be a nice addition to a display of antique equipment. But George is 73 now, and he’s decided the museum isn’t happening, so when the 3-D group came up with the idea to make a centaur for prom this year, the horse was pulled out of storage, carted back to the school, and cleanly beheaded.

“I think we should keep the head in case we ever do a Godfather theme,” Mark says, and the Prom Dads laugh. It’s nearly eight o’clock at night, and they’re taking a quick break before getting back to work on the dragon wings — painted fabric stretched over bamboo stakes. George is threatening, as he does every year, that this will be his last prom.

“We’re trying to talk him out of it,” says Rob Moses, another Prom Dad.

“Rob’s been here since ‘Going Gatsby’ 2016,” Mark explains. “We made a giant chandelier together.”

“I’m a short-timer,” Rob says. “At least my child graduated within the last 10 years.”

“We have a rule,” pipes in George, his voice gravelly. “We tell people that you have to stay 10 years past your last child.”

It was Mark who brought George here in the first place, back in 2012. George, whose son went to school with Mark’s kids, had lost his wife to cancer the previous year — and had recently battled it himself — and Mark told him the prom was a good way to fill his time, to have fun, to escape the heaviness, if just for a little while.

“And now I’m stuck here,” George grumbles.

Mark waves him off and goes to get the body of the dragon. It’s some 20 feet long, stuffed with packing peanuts. He places the body over the wings so I can get an idea of what the finished product will look like. The wings are too delicate to flap, Rob says, as though he’s trying to manage my expectations. But, Mark assures me, the beast will move back and forth across the gym. There’s a new Prom Dad this year — Chuck — and he’s volunteered to refine the track system.

A middle school art teacher from another district, Kate Stockton, has sculpted a five-foot torso out of chicken wire and plaster to attach to the horse. The torso is extremely muscular; they’ve nicknamed it Jason Momoa after the beefy actor who played Aquaman. Kate comes into the room and begins painting a tribal tattoo on Jason Momoa’s left shoulder. She had her senior prom here in 1996, the year after somebody landed a helicopter on the football field, necessitating a “no flying objects” parade rule. Kate ended up marrying and then divorcing her prom date; her son graduates from Pennsbury this year.

That’s the thing about Pennsbury: Many graduates stick around, buy a house in the district, and send their children here. Plenty talk about their graduation years in terms of the prom: “I graduated in 1997, ‘A Year of Medieval Magic.’” “I was 2001, ‘Night in Vegas.’”

“I was 1980. It was ‘Something Paradise,’” Mark says. (The theme was actually “Tropical Paradise,” according to the school’s list of every prom theme in Pennsbury history. Some have aged better than others; 1966 was “Oriental Enchantment.”)

Mark also ended up marrying his prom date, as did Joe Hartigan (1998, “Splendor on the Nile”). Joe’s daughter is a junior, and he’s returned to his alma mater to help in the final weeks. We walk to the lobby and look at the boat, now painted with a realistic wood grain. I wonder what it’s like for Joe to be back in the building all these years later. It seems everyone finds comfort in these walls, whether in a happy return to the past or, like George, a welcome respite from the present. Joe seems deep in thought, and I wonder if he’s thinking the same thing.

He turns to me, nods toward the boat. “I built the pyramids here in 1998.”

Two Weeks Before Prom

There’s an issue. A student group is working on the coat-check area, and Maggie has learned that seven of their 12 murals haven’t been started. She’s wearing another floral skirt and a plastic flower crown in her hair, which is now tinted purple. A roll of tape is looped around her wrist like a bracelet. The past few days have been productive, she says, but this is concerning.

In the gym, Jess sits cross-legged in the middle of a huge half-painted mural. It’s her second year on Prom Com — she’s a junior — and she’s in charge of decorating the rear main lobby with her friend Annie. Their design concept, based on oceanic mythology, includes a 3-D model of a Nordic sea monster, his snake-like body made of foil dryer ducts, and a coral reef crafted from Styrofoam, spray foam, loofahs, coffee filters, and pool noodles.

“Prom is my way of expressing art,” Jess says. “I have all these materials at my fingertips. I can do anything I want.” It’s a little hard to hear her over the persistent beeping of a scissor lift behind us. Chuck Dolan, the newest Prom Dad, is overhead. So far, he’s spent 11 hours doggedly filing the track of the trolley system that will carry the dragon across the gym, so it won’t get stuck.

“It’s going to work this year. I can feel it,” says Lindsay Gebeau, the gym teacher, as we look up at Chuck. Chuck has become obsessed with the dragon. Every time I see him, he’s on the scissor lift, fixated on the ceiling, the handyman version of Michelangelo.

Chuck is a retired communication, safety, and security consultant in his mid-60s. He’s soft-spoken, with a bushy mustache and kind eyes. His two kids are seniors — his son is graduating from Bucks County’s tech school, which has its own prom — and when he’s not working on the dragon, he’s busy constructing a 20-foot prom parade float.

“Sometimes it’s a good thing to just come and reset. I can focus on this instead of all the other crap I have to deal with,” he says. “It gives me better perspective.” Chuck had a third child, who died 26 years ago; he doesn’t offer details, and I don’t ask for them, but he mentions living at the Ronald McDonald House.

These white walls, a respite.

In other news, Medusa has a face now, sculpted by a bunch of seniors with chicken wire and papier-mâché. The immense body of the phoenix, hot-glued with hundreds of hand-cut and hand-painted foam feathers, is finished, and the wings have been successfully spread to full extension. The dragon’s head is complete too, with teeth, a tongue, and green light-up eyes. Jason Momoa is still waiting on hair extensions, but he has a beard and eyebrows.

At 7:30 p.m., I’m tasked with painting a jellyfish on one of the ocean murals. It’s been roughly sketched out, but the rest of the mural is so pretty, and I’m scared to start. A bunch of underclassmen urge me forward. “We don’t know what we’re doing either,” one admits. They help me find brushes and a paint container (an empty sour cream tub). So I sit in the middle of the ocean and begin painting.

A few hours later, close to 11 p.m., I gather my things to leave. The school has mostly cleared out, and the only sound is the low humming of the big blowers kids drag out to dry their murals before rolling them up. I walk through the lobby and find Lindsay, the gym teacher, lying on her stomach, sliding materials to Amanda, the English teacher, who is crouched beneath the capsized boat. I lie down on the floor too, and Amanda explains the problem: The boat, while impressive, wasn’t really designed with hanging in mind. All its anchor points are along the bottom center, and its 40-pound weight isn’t evenly distributed, so when the boat is eventually raised, it might sway, nose-dive, or, even worse, break in half like the Titanic. They’re trying to shore up the inner structure with thick Styrofoam wedges.

Amanda, Lindsay, and Maggie are all in their early 40s, moms of young children. Maggie is going through a separation and also caring for her sick parents. These teachers have spent the past few months working nonstop on this prom, often until midnight. They’re back at school before 7 a.m. Amanda lives in Philly; during the final week before prom, she’ll stay in a nearby hotel to be closer. I ask them how they do it.

“We just … love it,” Lindsay says, her face inches from the tile floor. “Hey, wanna use a band saw?”

I’m tired. I have to be up early to get my own young child to school. I’m covered in a fine blue powder from sitting in the ocean with my jellyfish. But the answer is obvious. Of course I want to use the band saw.

Two Days Before Prom

It’s 3 p.m., and the lights are dim in Room 232. The air is charged with anticipation. There are 20 kids here, along with a few administrators, but the star of the show is MaryAnn Daley, an English teacher (1984, “Oriental Paradise,” another theme that didn’t age well) who happens to look like she’s in a beauty pageant — long blond hair, perfect makeup, chic sheath dress, high heels. Our phones have been confiscated because MaryAnn is about to unveil the prom performer, and the announcement has been carefully orchestrated.

Rumors have been circulating for months and are still buzzing through the room: Pitbull, AJR, Taio Cruz, Drake. A student floats rapper Waka Flocka Flame, but this suggestion is quickly shot down. Someone mentions Ne-Yo; a girl brings up Sabrina Carpenter. “I’m manifesting it,” she says.

MaryAnn steps forward and gives a brief speech to remind the students that booking a prom performer is never guaranteed. If the kids don’t quite believe her, it’s understandable. Big-name entertainers have been a staple of Pennsbury proms ever since John Mayer played here in 2004 — a performance made possible by a student named Robert Costa, who besieged the crooner with unrelenting pleas for two years. (Unsurprisingly, Costa is now a national correspondent for CBS News.) MaryAnn has successfully wrangled prom performers for over a decade, curating a roster of music-industry connections in Los Angeles and New York and wielding her PR background — and sparkly charm — to persuade entertainers to play a 30-minute set for a relatively paltry fee. (She won’t give me numbers, but assistant principal Laura Tittle breaks the prom’s low-six-figure budget into thirds: decorations, food, and entertainment.)

“I think in some ways, we’ve become a victim of my success,” MaryAnn laments. “Every year I think, Is this the year I’m not going to get anybody? Is this it? Because it could happen.”

It almost happened, twice. The first time was in 2013, and panicked administrators finally gave up and booked a professional Lady Gaga impersonator. She wasn’t … well received. The next time was in 2017. MaryAnn had managed to book Questlove, but he backed out days before the prom, citing a dental emergency. Students and parents flooded his Twitter in fury, and kids launched a “save the prom” social-media campaign for DJ Pauly D, of Jersey Shore fame. In the end, Pauly D saved the prom, and Questlove, beaten down by the backlash, showed up in pain and played for free.

“HERE WE GO!” someone shouts, and a video starts. It’s very dramatic, and the excitement grows with each descriptor floating across the screen: “quadruple-platinum-selling single …” (murmurs), “Grammy-nominated …” (squeals), “featured in iCarly …” (shrieks), “… the Plain White T’s!” (screams). The band’s hit song, “Hey There, Delilah,” plays as everyone claps and files out of the classroom. The news spreads like wildfire. By the time I walk downstairs, the song is playing in the gym.

The mood is considerably darker in the lobby. Amanda reports that the first attempt to hang the boat didn’t go well. It’s upright, at least, supported by a complicated web of ropes and pulleys and a wood frame that Joe Hartigan built at the last minute, but I’m still recruited to help hold it steady for a bit. A girl runs by in a Viking hat, followed by Maggie, who clutches a three-page to-do list. The coat-check murals are still missing, the tufted clouds surrounding Zeus’s throne need to be finished, the constellation murals need fairy lights strung through them, and the kraken tentacles — seven massive 17-foot Styrofoam sculptures — still need some painting. In the gym is a wooden facade that will be covered in a mural of the East building ablaze; the phoenix will rise from behind it, a DIY symbol of Pennsbury’s old buildings being torn down and replaced by something new.

A mom named Leslie sits in a corner, stringing tinfoil fish on clear wire. She’s the one who collected all those paint containers, distributing fliers, putting a bucket outside her front door, and eventually delivering 35 leaf bags of empties to Maggie. It took a year. Leslie graduated from Pennsbury in 1994 (“Lands of Enchantment”), and her daughter, Liz, is a senior. She waves her over.

Liz, baby-faced and shy, has been helping with prom since sophomore year. “I struggle with anxiety and depression, and it’s really hard for me to make friends,” she says quietly. “When I found out I could come to Prom Com and create art, it became my outlet.” She made friends, found a community, brought herself back to life. As Liz talks, her mom looks like she might cry, but she keeps her head down, keeps stringing fish. Eventually Liz trots back to her friends and her mural, and Leslie leans over so I can hear her over the beeping of Chuck’s scissor lift: “This saved her.”

Friday, the Day Before Prom

Parade before Pennsbury High School’s prom

They’ve named the dragon.

She’s been christened Audrey, and she hangs in the center of the gym a few feet off the ground, suspended like a marionette. They’ve named the phoenix, too — Phineas — and given him a head. Jason Momoa has gotten his hair extensions, plus a loincloth, shield, and spear made by one of the Prom Dads. The 3-D team has been here since seven in the morning; it’s now close to 2 p.m.

A couple hundred people are at the school for setup; students buzz around in lime-green BEST PROM IN AMERICA T-shirts. A crew from Synergetic, a Bensalem-based audiovisual, lighting, and production company, has draped the gym in black fabric, set up concert-level lighting and speakers, and built a large stage. The boat has been hung in the lobby with a kraken tentacle, now painted, winding menacingly out of a hole in the bottom. False walls erected in some of the hallways direct the flow of kids. It’s disorienting, and I find myself getting lost. A crew of 100 students has spent hours sticking every vertical surface with thousands of little tape doughnuts for mural-hanging; the school looks like it’s been infected with some terrible skin disease. (They use more than 400 rolls of contractor-grade masking tape for prom each year.)

Outside, a crowd has gathered. They’re here — more than 24 hours early — to nab prime spots along the parade route, which winds down the path linking the East and West buildings, about half a mile. The school sent out an email instructing people to wait until 2:45 p.m., when the buses and student drivers will have cleared out, but nobody listened. By 2:30, dozens of tents have already been erected.

Parade before Pennsbury High School’s prom

“The floodgates just opened. I couldn’t stop them,” Laura Tittle tells principal Reggie Meadows. “I think we just have to shut down the campus next year.”

It’s hot out there, and windy — there’s a tornado watch tonight, and rain forecast for tomorrow; parents are scrambling to build last-minute canopies for the floats — but it’s freezing inside. They’ve cranked up the AC, chilling the school to 60 degrees for when 963 prom-goers pack in tomorrow — the highest turnout in years.

The next few hours pass in a blur of activity. By 9:30 p.m., most of the murals are hung. The teepees are up in the front lobby, dedicated to Native American mythology, and columns made of corrugated roofing have been crested with fake flowers and lined up in the “hallway of goddesses.” The wooden chariot attached to the Pegasus mural is in place, as are the cherry trees in the Japanese mythology-themed cafeteria and the Viking ship in the Celtic hallway. In Jess and Annie’s oceanic section, the coral reef is finished, and Jess’s sea dragon with the dryer-duct body is up. Someone turns on a black light, and the murals shine with glow-in-the-dark paint. People clap. Jess cries.

A few girls run up to me. “Did you see your jellyfish?” one asks, and they lead me to the mural, right underneath the boat. In my absence, they finished it for me and improved it — more shadowing, more dimension, better tentacles. “I’m still going to take credit for it,” I tell them.

Seventeen pizzas have been carted into the gym, along with a celebratory cake piped with loopy icing letters: BEST PROM IN AMERICA. Chuck is back on his scissor lift, raising the dragon, supervised by Prom Dads Mark and Joe. A man with a silvery-white ponytail, wearing a T-shirt from prom 1999 (“Paradise Lagoon”), stands quietly behind them.

This is Jim Minton, a former Pennsbury art teacher who retired in 2017. He tells me about his five-year tenure as prom director — how they had less time to set up, how they’d make bets on who’d be the last parent to leave. (One of the all-time winners is Mark, who once worked through the night, leaving at noon the day of prom.)

Parade before Pennsbury High School’s prom

“This prom just keeps looking for stuff. It’s always being fed by something. It never stops,” Jim says. It can’t stop. The kids love it, but the parents depend on it. One year, a frustrated prom chair threatened her senior class that prom would be canceled if they couldn’t get more student help. News reached the then-principal, who called Jim Minton into his office.

“He said, ‘I don’t care if you put blank sheets on the walls. This prom is happening. If I don’t do the prom, I’ll have to answer to the parents in this district, and I don’t want to face them. They’ll kill us,’” Jim recalls.

Jim still helps with the prom, but this is the first time he’s come by this year. His 50-year-old son died suddenly of a heart attack three weeks ago. Jim’s voice catches as he explains that he’s just wandering around to get out of the house: “It’s a getaway for a moment.” Plus, he gets to see his former students, now parents themselves. They call him over to show him their artwork. “You taught me how to do this,” they tell him.

These beautiful mural-covered walls, a respite.

The Prom Dads give up on the dragon around midnight. Audrey successfully made the journey across the gym a few times, but then she started getting stuck in the middle. She’d hang there while the cable stretched like a rubber band before releasing, lurching her forward with a scary bang. Chuck is up on the scissor lift, filing the track again. He looks defeated.

Right at 1 a.m., Maggie, Mark, Jess, and a kid named Will — he graduated last year (“Enchanted Environments”) and is home from college — gather in the lobby to see the latest addition: four big letters spelling PROM hanging from the ceiling, the O dangling from the kraken tentacle in the boat. Jess is already talking about her prom next year; she’s hoping for a national parks theme. Mark mentions building Mount Rushmore — maybe they could have the mouths move? Jess squeals; she wants to help with the construction.

Mark looks at me. “See? This is how it starts.”

Day of the Prom

“All hands on deck! Vips are coming at 10:30!” Jess shouts across the lobby. It’s 9:30 in the morning, exactly one hour before special administrators — including Thomas Smith, the superintendent of the Pennsbury School District — come by for a tour, and 90 minutes before doors open for the public walk-through. The first arrivals gather outside before 10 a.m.; soon the line will wrap around the school, at least a thousand people waiting to see the art. (“I was the year the helicopter landed,” I overhear someone say.)

“This is probably one of the biggest art installations in the entire state, and it happens every year. By high-schoolers,” says Will, the former student, standing next to a 17-foot tentacle. Overhead, Maggie — who was here with the other prom advisers until 4 a.m. — is on a lift, hot-gluing barnacles made of cut-up egg cartons to the bottom of the boat. An underclassman in a toga, her face and arms painted gray-green, walks by carrying a bow and arrow. She’ll be positioned on the red carpet, a living statue among toga-clad mannequins.

Prom Dad Mark is here, proudly holding his weeks-old grandson. His daughter — 2011, “Bucket List” — lives in New Jersey, so her son won’t go to Pennsbury. “We have to find him a prom date,” Mark says. (“Dad, he’s an infant.”)

People begin filing in at 11 a.m., mouths agape, heads on a swivel, phones aloft. Underclassmen are stationed throughout the school, holding signs with QR codes that link to a Venmo account for prom donations or to behind-the-scenes videos of the art in progress and the stories behind it. In the gym, a group of children sit before Phineas, and when the phoenix rises, they shriek in delight. “Look at the way the feathers articulate when the wings open,” Mark says. He spent the morning lubricating the dragon’s track with Teflon, and now Audrey is flying again.

“Look! The snakes on Medusa’s head are moving!” a dad calls out, dragging his toddler behind him. Two little girls pose for a photo on Zeus’s throne, and an elderly couple climb into the chariot. “Can you take our picture?” the man asks, holding out a digital camera. I hear a very old woman tell a security guard that this is the highlight of her year. A man named Steven tells me about painting murals for his prom here in 1970 (“Olde England”). He recently ran into his prom date at a water aerobics class. He’s leaving now, a $10 prom 2025 T-shirt slung over his shoulder, to have lunch before he settles in to watch two of his favorite things, both starting at 4 p.m.: the Phillies game on TV and, on his laptop, the livestream of the prom parade.

At 4:37 p.m., Amanda Durham bursts into Lindsay Gebeau’s office in the gym, a jumble of walkie-talkies held over her head like a trophy. She’s wild-eyed from lack of sleep but also glamorous, in a long navy dress and a sparkly brooch in her hair. She has news: There’s no internet, the administrators are yelling at each other, it’s rained so much that cars are sinking into the grass, somebody’s car is about to get towed, and they forgot to put the harpist’s name on the list, so security isn’t letting her in. Her update delivered, Amanda lets out a deep breath, drops the walkie-talkies on a chair, and swirls out of the room.

Maggie, still in her paint-splattered chambray button-down and art apron, gets back to counting donations from the walk-through: $513. (This doesn’t count T-shirt sales; they sold out.) Jess emerges from the girls locker room, looking elegant in a black sequined gown. She’ll be here all night, managing the 50 underclassmen who are working the event — passing hors d’oeuvres, manning the water stations and candy bar, clearing trash.

By the time the first vehicle, a fire truck, winds down the parade route, it’s cold and spitting rain. Still, hundreds of people from all over are here to see the spectacle, to take in the dresses, the cool cars, the over-the-top floats — more than 120 of them, some costing more than $1,000 to create.

“It perpetuates itself a little bit,” Principal Meadows says. “I’ve seen little boys and girls sitting at the parades watching, and you can tell they know they’re going to be here one day.”

Superintendent Smith goes further: “This isn’t a simple dance in a gym. It’s a full-scale production. It’s a community event that is part of the Pennsbury fabric. It is part of our DNA, it’s part of our culture, it’s part of our traditions, and it makes us who we are.”

After the fire truck, the first float rumbles by: nine kids lined up on a big flatbed decorated with clouds, a large mural, a Pegasus prop, a bubble machine, and a last-minute clear plastic canopy. The trailer is hitched to a pickup truck, and I cheer when I see the driver. It’s Chuck — of course it’s Chuck — wearing a tuxedo shirt, beaming, waving.

Joe, in a half-tuxedo and sunglasses, drives by next in his truck, music blaring. He’s towing 11 couples, including his niece, on a flatbed trailer bedecked with balloons, a 26-foot mural, and smoke machines. Joe has been building and driving prom floats for friends for seven years; this year, he finally bought the flatbed and even had a welder customize it for future proms. (“Because I have a niece who’s in first grade,” he explains.)

The school lobby is an explosion of noise and commotion. Kids fresh off the red carpet are checking in, getting wristbands, snapping photos, already swapping spindly heels for athletic socks. The gowns look like candy — saffron yellows, pale blues, royal purples. There are sequins, feathers, ribbons, thigh-high slits, corset backs. Many of the suits are just as colorful. Everything shimmers under the strobe lights.

At 6 p.m., Chuck walks by carrying a big pole. He volunteered to work the prom, stationing himself in the gym so he can keep an eye on the dragon. He uses the pole to flick a switch high overhead, and Audrey begins to fly, slowly. It’s perfect timing, because at 6:30, the prom royals are announced. For the first time ever, the top two vote-getters in the prom court are two girls, instead of a boy and a girl. They came separately, one with her boyfriend, and they accept their crowns in a flurry of hugs and squeals and tears.

This will be the main drama of the evening, and it will play out on Facebook, where a bunch of adults blast their anger on the high school’s page: “Pennsbury has gone woke!” “This is not Pennsbury tradition!” One person takes it in stride: “Well at least it wasn’t the kid who pretends to be a cat.” The adults are angry about everything, including the possibility that their tax dollars might be funding a woke event. “I gave Jen some talking points,” Reggie Meadows sighs, referring to the school’s head of public relations. Namely: Taxpayer dollars don’t fund the event in any capacity; the school first eliminated “king” and “queen” categories a few years earlier, at Sports Nite. He seems exhausted by all the nonsense.

But these kids aren’t looking at Facebook right now. They’re in the gym, screaming as loudly as they can, because the DJ just asked them: “IS THIS THE BEST PROM IN AMERICA?!?” The party is in full swing. The phoenix rises again and again; kids take pictures next to Medusa and Jason Momoa; Audrey makes her slow 10-minute loop across the gym. The bass is a thud in my chest, and the smoke machine turns everything fuzzy and filtered.

“I feel like I’m watching a prom scene in a 1980s movie,” I say to Chuck.

He laughs. “It’s just like a movie.”

At 7 p.m., the faculty band, fronted by a science teacher and a history teacher, wraps up in the auditorium. Hypno Lorenzo, the new hypnotist, is on next; the longtime hypnotist, Barb, finally retired after decades. (“He’s from Connecticut — $1,200!” Laura Tittle exclaims.) One of the prom royals, picked to be hypnotized, leaves her crown on. I hope she hasn’t scrolled Facebook recently.

Chuck and I have dinner together in a small room off the cafeteria. He tells me about his kids, one headed to the University of Oregon in a few months, the other off to New York City. I ask if he’ll help with the prom again next year. “Probably. I need something to do. I can only build so many Christmas floats a year,” he says.

It becomes clear to me that kids are the transient part of all of this, rolling in and out like the tides. The adults are the anchors — teachers and parents holding a tradition in place, preserving it for young people who might one day identify themselves through this moment (2025, “Mythology”). These adults are in the cafeteria, serving dinner to hundreds of kids in hopes of catching a glimpse of their own. They’re in the coat-check hallway, which finally got all its murals — longtime mom friends savoring the last event before graduation. “We’ve been volunteering together since our kids were in kindergarten,” one woman says. “It feels like yesterday. I cry all the time.”

They’re standing by the wrestling room, marveling at the work of their children. “I’m just so proud,” Leslie says. “All of these murals, Liz worked on every single one.” Liz is here somewhere, she says, and then breaks into a huge smile: “I haven’t seen her all night.” (I spot Liz later, and she’s radiant. A phoenix.)

These adults are in the gym, watching over the dragon, which has stopped turning and now makes her inbound trip backwards. I’m not sure how Chuck and Jim Minton go on; I can’t imagine losing a child. I look at Chuck in his tuxedo shirt, the pole in his hand in case he needs to help Audrey. I suppose managing grief isn’t about slaying the dragon. Maybe it’s simply understanding that it’s there, sometimes watching it from afar, guiding it, transforming it. Making it beautiful.

These adults will be here first thing tomorrow morning, armed with ladders and drills, taking everything down. The public is invited to come cart away what they want: An Irish dance studio will take a mural from the Celtic hallway; a man will take the cherry trees for a middle school dance. The high school musical director will keep Medusa and a couple of columns. A Prom Dad will keep the dragon’s head, which he carved. Two moms will take oceanic murals for their sons’ middle school graduations, and one will nearly cry. (“I need a purpose now — is this my purpose?”)

A little after 10:30 p.m., MaryAnn Daley, wearing a glitzy one-shoulder cocktail dress, takes the stage to introduce the Plain White T’s. The band has been hanging out upstairs in her classroom, which she turned into a makeshift green room with rented furniture and catering. Earlier, they had a brief meet-and-greet with the prom chairs and an interview with the senior class president, who confessed that she was born a year after “Hey There, Delilah” was released. (“We all got into music in high school, so any chance to come and play in front of high school kids is kind of the coolest show ever,” the band’s lead singer, Tom Higgenson, said when asked why he agreed to play the prom.)

As the band begins, the kids jump up and down, press against each other, raise their hands in the air. It’s a typical prom scene, because eventually, the Pennsbury prom becomes just like any other school dance. In the end, everyone is dancing or sitting on the sidelines or staring at their phones. Someone is crying in the bathroom; someone is falling in love; someone is promising that things won’t ever change, even though they probably will. The gym floor is speckled with feathers and flower petals and glitter. The phoenix rises and the dragon flies and the band plays a song and the kids sing along: “It’s all, it’s alright, we’re gonna get old, but we’re young tonight.”

Published as “A Night to Remember” in the September 2025 issue of Philadelphia magazine.