Calder Gardens Is Coming to the Parkway — and It’s Unlike Anything You’ve Ever Seen

A homecoming for one of art’s boldest visionaries, Philadelphia’s new urban sanctuary is ready to reimagine what a museum can be.

A rendering of the soon-to-open Calder Gardens on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway / Rendering by Herzog & de Meuron

“You know, I was on the brim of Billy Penn’s hat,” Sandy Rower recalls, pointing to the William Penn statue atop City Hall, hoisted up in 1894. “I went up the hatch they use for cleaning and stood on top of his hat.” When I blanch at the thought of being a tiny speck standing 550 feet above the street on a giant Quaker hat visible for miles in all directions, Rower assures me that the famous landmark had been surrounded by scaffolding. Invited to check out his great-great-grandfather Alexander Milne Calder’s statue during its 1980s restoration, Rower was able to get to the hatch by climbing steps, taking elevators, and finally ascending through the interior of Penn’s face by way of a metal ladder. Rower, the 62-year-old grandson of Alexander “Sandy” Calder and president of the Manhattan-based Calder Foundation, recounts the entire adventure with complete nonchalance. For Rower, it’s just another extraordinary event for the Calders, a family of Philadelphia sculptors known for cultivating a life and a world less ordinary.

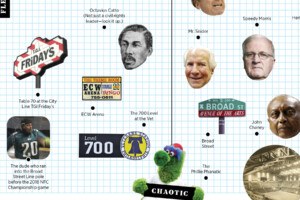

Rower’s in town to check on the progress of Calder Gardens, the much-anticipated cultural institution with an unconventional approach to presenting his grandfather’s art. The space, along the Ben Franklin Parkway, opens to the public next month. Rower is here to talk to me about this audaciously world-class addition to the Parkway, designed by acclaimed Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron and Dutch garden designer Piet Oudolf. Calder Gardens — which Rower calls an “urban sanctuary” — will showcase the sculpture and ideas of Sandy Calder, one of the most important sculptors of the 20th century. With artwork in every major museum around the world, Calder now gets a home here all to himself.

We walk on rain-soaked gravel surrounding the Swann Memorial Fountain in Logan Circle at 19th Street and the Parkway during an unexpected cold snap in May. Rower’s great-grandfather, Alexander Stirling Calder, made The Fountain of Three Rivers (the fountain’s sculpture, with its three bronze figures representing the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers and the Wissahickon Creek). “I love Milne’s work,” says Rower, “but I love Stirling’s even more and the way he tells stories. I love the fact that the son went from municipal sculpting to being somebody deeply romantic and deeply poetic.” Then Rower turns his gaze from the fountain, past the Calder Gardens construction, farther west to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where his grandfather’s 30-by-35-foot Ghost mobile hangs in the Great Hall. If you look out the front windows of the Art Museum, you can see a lineup of the most famous Calder contributions to Philadelphia down the length of the Parkway. In Sandy Calder’s 1966 autobiography, he wrote irreverently, “So now [Philadelphians] say they have ‘the Father, the Son, and the Unholy Ghost.’”

Rower is here to observe the site progress. The main stainless-steel “shed” is up and covered in a plastic coating to protect its facade while work continues. In the months before the opening, if you were to drive past you would see a chain-link fence with workers inside the enclosure scurrying about in hard hats, wheeled excavators moving earth, and construction materials in various piles. Trees are already being planted, but with four months to go, it is still very much a work in progress.

A Calder project has been in the works for so long in various incarnations — starting when Ed Rendell was the mayor in the late 1990s before being stalled, stopped, reimagined, relaunched, delayed by the pandemic, and rebooted — that for it to be finally opening in September seems like a minor miracle. But we are the beneficiaries of this long incubation period. Now, instead of adding another traditional museum to the Parkway, we are getting a completely different kind of cultural institution, one where curators aren’t spoon-feeding you data points, where you’re given the freedom to roam, react, and interpret for yourself. The Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Barnes Foundation, and the Rodin Museum can now welcome a new neighbor that aspires to give visitors a radically different experience and pays homage to Calder’s artistic legacy. Calder Gardens fills in the last remaining spot on the Parkway, completing a lineup of world-class cultural attractions worthy of inspiring some hometown pride.

Before Sandy Calder, all sculpture was rooted to the ground or a facade. He had a talent for conceptualizing new ways to make art and was fascinated by sculpting space — what’s between the shapes in his works — and he had no problem challenging the established rules. His wire sculptures had no precedent, and his mobiles liberated sculpture from its traditional earthbound location, refashioning the definition of what sculpture could be.

Calder’s wire sculptures, which he began making in Paris in the 1920s, essentially abandoned his father’s and grandfather’s approach to materials and form. Forget bronze or marble statues on pedestals or affixed to buildings. All Sandy Calder needed was a ball of wire and a pair of pliers, and, presto, he could make a 3D wire portrait of anyone.

Born in 1898, Calder grew up in a household of artists. Both parents attended the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (as had his grandfather, after emigrating from Scotland). Yet he would go on to surpass them all in creative stature, with works commissioned around the globe, from Chicago to Beirut, Paris to Caracas, and places in between. (At a 2022 auction, his mobile 39=50 sold for $15.6 million.) His parents had two children, and Calder spent a brief period in Philadelphia — even attending Germantown Academy for a few months — but spent his childhood moving around with his family from Philly to Arizona, California, and New York. He’d later enroll in college at the Stevens Institute of Technology in New Jersey. But a career in mechanical engineering didn’t suit him, and he more happily attended the Art Students League of New York a few years later.

Subsidized by his parents, Calder headed to Paris in 1926, where he made the sensation known as the Cirque Calder, which was a complete miniature circus with components fashioned out of wire and found materials that he would “perform.” From this, he experimented further with wire as a medium before arriving at the earliest iteration of his mobile. Credit for naming the new type of sculpture goes to artist Marcel Duchamp. Calder asked him what he should call his invention. “Duchamp replied, ‘C’est mobile,’ which is referring to both motion and motive in French. He’s making a pun. Calder thought this was amazing,” explains Rower.

Calder came of age in the 1920s, with all the exuberance, prosperity, and refashioning of public norms the time between the wars produced. Critics have said Calder cultivated the feeling among some people that he was like a holy fool. He didn’t believe in society’s rules and dictates. He famously wore big red work shirts most days, even to fancy exhibition openings, yet he also traveled in sophisticated circles, surrounded by friends including playwright Arthur Miller, cartoonist Saul Steinberg, surrealist painter Joan Miró, and modernist painter Piet Mondrian. This is one of the missions of the Calder Foundation: to reverse the holy fool idea and instead present the radical and innovative nature of his work. Calder may have appeared to be a bohemian with a penchant for wine and wild samba parties, but he was also a deep philosophical thinker with a rigorous commitment to his art.

Through the decades, Calder and his wife and two daughters would travel back and forth between homes in Roxbury, Connecticut; New York City; and Saché, France, in the Loire Valley, where he was able to build a studio big enough to make his mid- and late-career monumental sculptures, known as stabiles. Though Grand Rapids, Michigan, can claim one of Calder’s biggest stabiles, La Grande Vitesse (43 feet tall, 54 feet long, and 30 feet wide), Philly can claim the biggest mobile in the world: the massive White Cascade (100 feet long by 60 feet wide) installed at the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia at 7th and Arch streets.

Calder never stopped creating and had a prodigious output throughout his life, including wire sculptures, his miniature circus, mobiles, stabiles, drawings, and even inventions to improve his home kitchen, such as five types of toasters. He also made jewelry and toys, painted anti–Vietnam War posters, and designed exteriors of a BMW race car and a Braniff Airways jet. (Of course, it was natural that Calder would want to see his art in motion flying through the skies or zooming around a racetrack.)

Arne Glimcher, the founder of Pace Gallery, described Calder’s work this way in a 1998 PBS American Masters episode: “It shatters the illusion of everything sculpture ever was. It is unlike any body of work created this century. He changed the nature of sculpture. He redefined what sculpture was, could possibly be, and now is.”

Years ago during an interview, the late Anne d’Harnoncourt, director of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, told me that Calder’s Ghost mobile had been misassembled after a cleaning. I checked with Rower, and he confirms that he was the one who informed the museum, adding that rehanging a mobile is a pain. He says you have to assemble scaffolding to stabilize the entire sculpture, “because when you unhook something and you’ve taken all the weight off, it could collapse and fall to the floor. So you have to hold it all in position while you do what you have to do.”

Somewhere in there is an analogy for Calder Gardens. Some kind of magical art scaffolding held all the hopes and dreams in place until things were in position to make it happen. It was Rendell who, with a simple phone call in 1998, put all this in motion. Rower recounts that Rendell, after reading a New York Times story about the difficulty the foundation was having with New York’s then-mayor Rudy Giuliani to buy a city-owned building, called Rower to see if he could make him a better offer. Rower was thrilled. When Rendell invited Rower to the city to check out possible sites, he quickly accepted.

Calder’s grandson was no longer interested in a traditional museum. Rower wanted a different concept: an urban sanctuary. Like his grandfather, Rower was about to make a radical turn to create a place where people could experience art in a new way.”

Momentum and support began to build. Developer Willard “Bill” Rouse, known for his ability to get things done, was exploring ideas with Rower. (It was Rouse who in 1987 was the first to break the long-standing unwritten agreement that no building in the city should be higher than Billy Penn’s hat with his 61-floor One Liberty Place.) They went as far as to ask architect Tadao Ando to make some drawings. “Bill and I spoke the same language. He was incredibly persuasive,” says Rower. “Then Bill died. It was a total shock. There was nobody to pick up the pieces.”

After Rouse’s 2003 passing, the project languished. Next came d’Harnoncourt, who contacted Rower to revive the project, but she was also raising millions for the renovation of the museum’s Perelman Building, says Rower. She died unexpectedly in June 2008.

And then along came the men who would become the project’s two most significant allies: philanthropists and businessmen Joe Neubauer and Gerry Lenfest. Neubauer, the retired chairman and CEO of Aramark, and his wife, Jeanette Lerman-Neubauer, are trustees of the Neubauer Family Foundation. Lenfest, who had made billions through the sale of his cable company in 1999, was also known as a philanthropic force in town. Rower says the two friends, who had been instrumental in bringing the Barnes Foundation from Merion to its new home on the Parkway in 2012, committed to Calder Gardens. According to Rower, Lenfest, who died in 2018, said to Neubauer before his death, “‘I need you to do this for me.’ No one could say no to Joe, but Joe couldn’t say no to Gerry.”

Neubauer, who owns four Calders and whose foundation is the lead private funder for the project, says he and the executive director and president of the Barnes Foundation, Thom Collins, were meeting Lenfest in his Conshohocken office. “After lunch [Lenfest] said, ‘Sit down. I want to talk about one other thing before you go,’” recalls Neubauer. “He talked about reviving the Calder project. He said, ‘You ought to do it.’” Later, during a dinner celebrating the fifth anniversary of the Barnes in 2017, Lenfest pressed again, according to Neubauer, and turned to him and Rebecca Rimel, president and CEO of the Pew Charitable Trusts, and said, “We have to revive the Calder project on the Parkway. And here’s how we’ll do it. I’ll give $10 million, and Rebecca, you give $10 million, and Joe, you give $10 million, and we’ll get $10 million from the governor.”

When Neubauer called Rower, Calder’s grandson was no longer interested in a traditional museum. Rower wanted a different concept: an urban sanctuary. Like his grandfather, Rower was about to make a radical turn to create a place where people could experience art in a new way. Rower aspires to engage visitors the way Calder wanted, to enable them to commune with the work. Rower hopes the gardens will transport people and be a place to “activate energetic forces” and for a “kind of engagement that is sensitive and also a little mysterious.” “There’s this thing going on for us humans that is really a positive force, and it is also what connects us,” he says. “These mysteries are what Calder’s art is all about.”

A skeptic might wonder if this talk of energy would suit the sculptor famous for his practical genius. “He didn’t look at it from these esoteric points of view,” concedes Rower. “He looked at it more … not from a science perspective, but from a natural reality perspective.” Rower believes an introspective experience where time is slowed down (or eliminated completely) aligns with his grandfather’s exploration of our world. Albert Einstein himself famously became mesmerized by Calder’s 1934 motorized work, A Universe, staring at it for its entire 40-minute cycle when it was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

Neubauer appreciated this vision of an urban oasis. “Art is important to the population of any large urban community,” he says. “Art gives people a break from the day-to-day stuff, especially outstanding art, which both the Barnes Foundation and Calder art are. These institutions give people a point of pride that they have them in their community and can participate in it.”

The $90 million project — announced in February 2020, ground finally broken in 2022 — is now almost at the finish line. (The city leased the land to the Calder Foundation at no charge for 99 years.) The pandemic made coordination between city departments unpredictable, including the response to discovering a water main underneath the site and 2021’s Hurricane Ida. “When you get a phone call, ‘We found a 40-inch high-pressure water pipe running through the middle of the block,’ you go ‘Whoa, what do we do now?’” recalls Neubauer. “And when 676 becomes a bathtub and everyone worries about water pressure pushing on a building below garden level, you think how much more concrete do we need to pour into here? We had 190 cement trucks and rebar put into the site.” As for being the visionary to get Calder Gardens from idea to reality, Neubauer says, “I just like to get things done.”

Neubauer believes it was worth all the headaches to have this world-class triumvirate of innovative artists and designers — Calder, architect Jacques Herzog, and garden designer Piet Oudolf — united in one location in Philadelphia. It’s an undeniable cultural destination sure to attract tourists and locals alike, as well as being a source of economic development for the city. “To be able to bring all of that to Philadelphia and the Parkway is a beautiful gift to the community,” he says. “I wasn’t born in Philadelphia, though I’ve lived here for 40 years, but I’m trying to help make things a little bit better for everyone in this community in any way I can.”

As I walk along 22nd Street toward Calder Gardens, I hear a barrage of noise: on-ramps and exits and drivers honking and jockeying for better lanes, the constant whoosh of cars already on the Parkway. A guy on a dirt bike tears down the center lanes, engine screaming. Even a nearby ice cream truck with its jingle on a tinny loop projects a slightly manic quality. With the overwhelming car-to-human ratio and general din, I get the appeal of Calder Gardens as a sanctuary away from the churn of frantic city energy.

I’m meeting Juana Berrio, the senior director of programs at Calder Gardens, who was hired in February from her position as an adviser with the Whitney Museum’s Independent Study Program to oversee daily operations here. Coming from the direction of her temporary office at the Barnes Foundation, Berrio crosses 12 lanes to reach me and gives me a friendly wave. The Barnes is affiliated with Calder Gardens to help minimize overhead costs by providing administrative and operational support. Berrio invites me to tiptoe up the dirt-speckled path lined with safety cones toward the site’s main building. We get to the space in front of the main building and turn around to imagine what it will soon be. Berrio tells me construction will be finished by early July, and the artwork will be installed over the following two weeks. Oudolf, the 80-year-old legendary garden designer, is visiting next week to supervise the arrival of 37,000 perennials (including hairy beardtongue, clustered mountain mint, Culver’s root, and meadow rue, to name a few) to be arranged and planted. The celebrated Dutch gardener has elevated what some might call the humble work of garden tending to a level of creativity and thoughtful urban design that can be revelatory for those who experience it. (Notable examples of his work include New York’s High Line and London’s Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park.) That’s the plan here, with six different gardens working in concert with the art and architecture to create the urban retreat.

Things are moving fast on the site. Berrio points out two curved pathways for visitors that weren’t there even two days ago. She tells me the stainless-steel facade of the main building will create a stunning mirror effect that will reflect Oudolf’s gardens. Architect Herzog has had to use his prize-winning talents on a tiny scale for this commission — even going deep underground to maximize the limited space available. Known for large-scale works such as London’s Tate Modern and Beijing’s “Bird’s Nest” stadium, the firm’s interest in this pocket-size project is surprising. “I was talking to Jacques Herzog in Basel,” says Neubauer. “I questioned why he would take this assignment. He responded that this is a challenge for him, to create a stage where Calder art will be displayed on a rotating basis. Something like this has never been done before.”

Calder Foundation president and Alexander “Sandy” Calder grandson Sandy Rower / Photograph by Aaron Richter

Nothing would have made Calder happier than to collaborate on a project with Herzog: Calder loved architects because they combined aesthetics with practical application, which is what he did too. Berrio tells me the melding of art, architecture, and nature for this untraditional museum shifts the emphasis to learning something about yourself. “It’s an invitation for a full holistic experience, for the soul, the mind, and the body. … The fact that we are in a garden is an invitation to notice impermanence, which is such an important element of life.” She wants visitors to think about interconnectedness, so it’s no surprise that her programming ideas include meditation and mindfulness. She has plans to bring in poets, musicians, scholars, and wellness practitioners for special programs, as well as to create a monthly film club and sound series. Everything is still up for discussion, but she mentions the idea of lending meditation pillows to visitors looking for some self-discovery.

With a mission to be nondidactic, the space will have no wall labels. “My mission is not to interpret the work. And not to allow other people to interpret it for you,” says Rower. “There’s nothing mitigating your experience. There’s nobody telling you what to think. That might be frustrating for some people who might want to know what the date is and what’s the title, but it’s not the purpose of this place because it’s not a museum. And there’s no exhibition. It’s just you being with a work of art.”

A danger in doing away with wall panels and curatorial help is that people may feel bewildered. Berrio is quick to clarify that they don’t want visitors to feel they have to be art scholars. Maybe visitors can turn to a neighbor and ask what they know about a piece, or what they think it means. This reminds me of an idea I’ve heard, that mobiles are about a sense of community and connectedness. Mobiles might be a representation of how things, people, nanoparticles, planets — pick your example — relate and connect in a community, a family of forms. Calder’s art gives you the time and moment to think about how everything relates to everything else — whether it’s bees buzzing in the gardens pollinating flowers or the neighbors whose politics you might not like. Everything is connected in some way, and slowing down to consider that web of connection may make us better, more thoughtful members of society. But that’s just one interpretation. You’re welcome to your own.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to clarify Calder’s place of birth.

Published as “Space Odyssey” in the August 2025 issue of Philadelphia magazine.