Ignore the Rankings: Why the Best School for Your Kid Is Probably the One in Your Neighborhood

After years of obsessing about stats and lists, many city parents are discovering their kids will get a great education right around the corner.

After years of obsessing about public school rankings, many city parents are discovering their kids will get a great education right around the corner.

It can be very hard to be in the minority in a social or professional setting. Those in the majority may look askance at you, or even question your right to be where you are. Your competence may be called into question, and other well-meaning souls may act patronizingly toward you out of good intentions. All of this will do a number on your self-confidence.

Given all that, it should be no wonder that people seek environments where these things won’t happen — psychic safe spaces and emotional comfort zones where one can keep one’s self-esteem intact.

What’s all this got to do with choosing a school for your child?

This: We (or should I say “you” — an affluent white couple, potentially) say when we (or you) go school-shopping that we want a school where our children will excel. One where they’ll have dedicated teachers, plenty of resources, and lots of support and opportunities for enrichment.

Oh, and if possible, a diverse student body.

An entire industry, of which this issue of Philly Mag is just one small part, has emerged to guide parents to such schools. It offers grades, rankings and metrics intended to help parents make one of the most important decisions they ever will, up there with choosing a place to call home.

In fact, the two are usually intertwined. Parents will relocate to communities solely on the strength of their schools.

And when they do, diversity is usually the one factor that goes out the window.

This is especially true for city residents who are otherwise satisfied with their neighborhoods and neighbors. It’s almost a cliché: Unless they’re living in a few fortunate neighborhoods with schools anointed as “great,” middle-class or higher city families usually pull up stakes and head for a suburb when they contemplate sending kids to school.

This article is written for those residents especially, but also for anyone who wants to choose a school where kids will learn lessons that will serve them well in the future.

Why do I feel qualified to write it? Well, I’ve been in the minority just about all my life, especially when it comes to education.

From kindergarten through college, I never attended a school where most of the students looked like me. And from kindergarten through third grade, there were no other students who looked like me.

This makes me an exception to the rule in this country — and, I submit, gives me more than a little insight to this subject. Some of the advice that follows is based on my own upbringing in a large, highly segregated city in the Midwest.

But I’ve also gotten schooled by people, Philadelphia residents all, who have decided that diversity is in itself valuable enough to scrap the usual assumptions of what makes a school right for their children.

What these parents, and I, have learned is this: Your child will, in all likelihood, do every bit as well in your neighborhood public school as at a school that ranks highly on rating sites or magazine lists, even if the neighborhood students don’t share your demographic or socioeconomic status.

Before I get into the nitty-gritty, a few words on why most affluent or even merely middle-class white parents end up sending their kids to schools where the bulk of the students look like them.

From the late 1960s onward, public schools in city after city began to fail the children they served. The students in these schools weren’t getting the education they needed to ensure a solid middle-class existence.

This sad state of affairs had many causes. One of them was the exodus of whites from the cities.

The author at his childhood home in Kansas City, 1966.

I can remember being four years old, not yet ready for kindergarten, and playing with a white kid who lived over the back fence from my home on the east side of Kansas City, Missouri. The neighborhood I lived in resembled West Oak Lane, Mount Airy or Wynnefield here in Philadelphia. People, all of them white and many of them Jewish, had built comfortable lives there; starting in the 1950s, its residents were increasingly Black. My parents bought the house I grew up in in 1954, four years before I arrived on the scene.

By the time my kindergarten year ended, no white families remained on my block or the blocks around mine.

And while my parents chose to remain in the neighborhood, they chose not to send me to school there. Instead, they sent me to a public grade school across town. It offered some advantages over my neighborhood school: It was the smallest public school in the city. It was right next door to the University of Missouri-Kansas City campus, which meant that UMKC education students made summer school there an opportunity to learn even more, rather than a catch-up exercise. (In a quirk I consider karmic in retrospect, the school was named for the founder of the Kansas City Star, William Rockhill Nelson.)

And it wasn’t overcrowded like Kumpf, my neighborhood public school. Kumpf was so jam-packed that the city school district began busing kids from it to Nelson starting in the fall of 1966, when I was entering third grade.

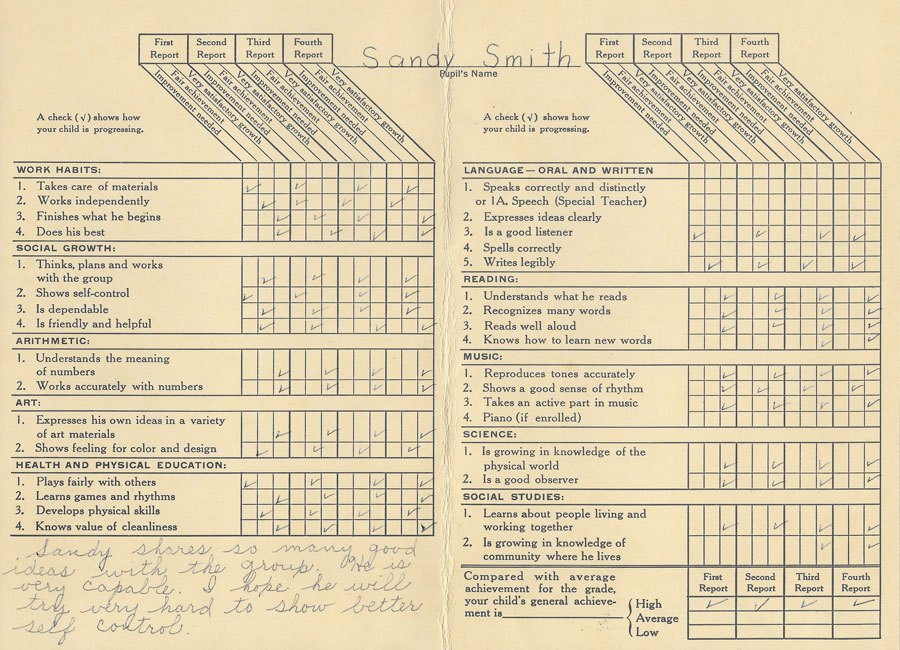

The author’s first-grade report card from William Rockhill Nelson School, 1964-’65.

Once that happened, I was no longer the only Black kid in my class. Racist taunts from classmates — thankfully few in number — ceased. Since both the kids at Nelson and the ones bused in from Kumpf were well-behaved, there weren’t the kinds of tensions one sometimes hears of when a sudden influx of “outsiders” infiltrates an established social order. Since I had already been there, I went from being one of Them to being one of Us in the eyes of my white classmates.

Those classmates, however, never were and never would be Them to anyone other than the Black residents of the East Side. They were the ones who defined good behavior. They were the ones whose parents (some of them, at least) ran local businesses and institutions. They would never have their legitimacy questioned.

The author’s senior class portrait from Pembroke-Country Day School, 1976.

And even though I modeled my behavior on theirs, more or less, that last would happen to me, eventually. And the questioning would come from Blacks as well as whites. When I got to Harvard University in the fall of 1976, I got publicly humiliated in my house dining hall by other Black students who judged me insufficiently Black thanks to my mannerisms.

But as I was making my way through school, a drama was playing out in Kansas City, and Philadelphia, and a host of other Northern cities whose schools were segregated not by law, as Kansas City’s were before Brown v. Board of Education, but by fact and practice.

Beginning around the time my mother enrolled me in a local private school in 1970, the city schools experienced a long, slow and painful decline, triggered by voters repeatedly rejecting school tax hikes. Around the same time — in 1973, to be exact — the Supreme Court ruled that de facto segregation, which Kansas City still had, was as illegal as segregation required by law. That ruling would place cities like Philadelphia in the school-integration crosshairs, too.

Like many Midwestern cities, Kansas City has long had a deep racial divide: Even though it’s blurring, people there still know what you mean when you say “east of Troost” and “west of Troost.” The north-south thoroughfare splits the older part of the city almost evenly in two, with whites living to its west and Blacks living to its east. (Of course, I lived east of Troost Avenue and went to school west of it.)

On top of this, thanks to a change in state law in 1957, while the city could annex its surrounding suburbs, it couldn’t merge those suburban school districts with the city district. This would ultimately turn the city district majority Black.

In Philadelphia, where residential segregation is more of a patchwork quilt, the story was slightly different. The school district maintained segregation by drawing up attendance zones so that schools were either all-white or all-Black. It even segregated school faculty: Black schools had Black teachers, while white schools had white ones.

Despite their differences, both cities ended up on the receiving end of lawsuits seeking to ensure integration. Here, the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission sued the school district to end its segregationist practices. There, the Kansas City, Missouri, School District moved to head off a lawsuit in 1977 by suing suburban districts, the state, and various federal agencies for causing and perpetuating city school segregation.

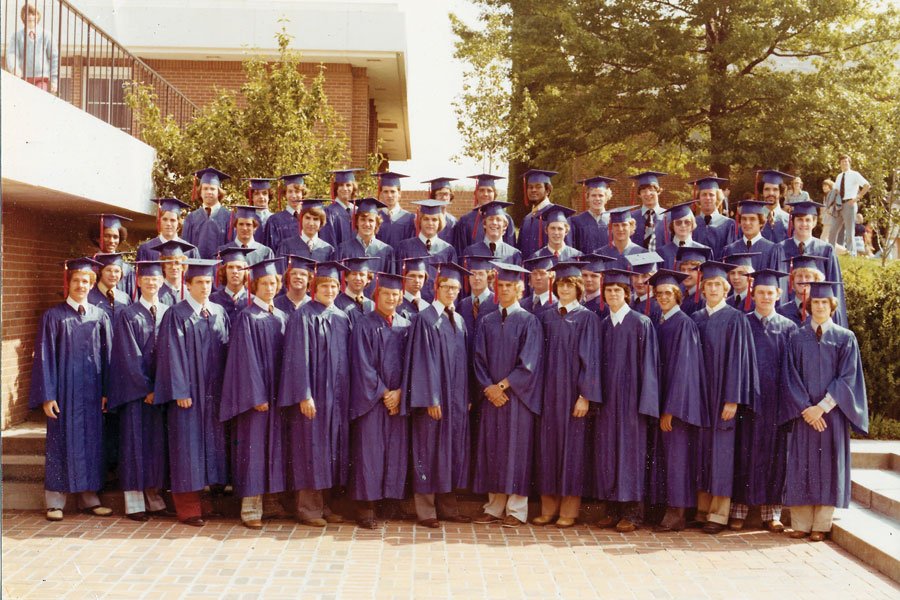

The author’s Pembroke-Country Day School graduating class; he is in the third row at the far left.

The federal judge hearing the Kansas City case threw out the district’s suit and made it a defendant instead, thus launching one of the longest, most complex and costliest desegregation cases in our country’s history. Yet the cases in Kansas City and Philly still had similarities. Both cities wished to avoid mandatory busing. And both ultimately relied on citywide magnet high schools as a remedial measure. In Kansas City, the judge ordered the city school district to spend $2.1 billion on state-of-the-art schools for which every taxpayer in Missouri would ultimately pay.

It was the “Field of Dreams” theory applied to real life: Build the schools, the judge and the district argued, and the white students will come from the ’burbs. The trouble was, they didn’t. Strictly enforced racial composition targets for the schools, one of which was so lavishly outfitted that an attorney for the state of Missouri called it the “Taj Mahal,” meant that many of the Black students were unable to attend them, because the schools hadn’t enrolled enough white students from the suburban districts. Thus, schools operated below capacity.

Philadelphia already had a few schools that drew their students from all over the city: Central, Masterman and Girls’ High, the three elite academic high schools; Bok, since closed, and Dobbins, both of which focused on vocational training; and W.B. Saul, one of the few big-city high schools with an agricultural focus. To these were added the Philadelphia High School for the Creative and Performing Arts, Bodine High School for International Affairs, George Washington Carver High School of Engineering and Science, and at least seven other specialized academies.

Because residential segregation in Philadelphia took a slightly different form than it did in Kansas City — instead of vast swaths of the city being all-Black or all-white, Philadelphia had some Black neighborhoods close to other white ones — the city had an option many other cities didn’t: make the existing neighborhood schools appeal to white as well as Black families so more of them would keep their kids in the public schools.

That didn’t work out quite as the School District of Philadelphia had hoped. In racially integrated Mount Airy, for instance, the city added extra services, such as all-day kindergarten and after-school child care, in hopes of keeping white families’ kids enrolled. But the extras didn’t stop whites from pulling their kids out: Of the six grade schools whose catchment areas include at least part of the neighborhood, all but one have more than 80 percent Black student bodies.

The one exception is the Charles W. Henry School in West Mount Airy. And what has happened to it over the past few years could signal a major change in the way many parents think about neighborhood schools in the city. But before I get around to telling that story, let me say something about how parents got to thinking the way they do.

It began with good intentions. As city schools increasingly turned out students who couldn’t read at their grade level, efforts to reverse the trend arose.

One of those efforts was charter schools. These are independently run public schools that get to set their own educational standards and practices. Eighty-seven charter schools all over Philadelphia enrolled 67,699 students this past academic year — a little more than half as many students as are enrolled in district-run schools. Another 7,677 students took classes at home via cyber charter schools.

Not long after charters started spreading, the federal government sought to raise the performance bar for every public school. A George W. Bush administration law, the No Child Left Behind Act, called on states to test students in reading and math in grades three through eight and once in high school. The goal: to improve students’ individual outcomes.

The data those tests provided were intended to help districts identify schools that needed additional resources and support in order to improve. And the test scores and other data have been used by sites like GreatSchools.org to help parents evaluate schools.

The trouble is, those rating sites rely heavily on those test scores to rank and grade schools overall. Many parents have thus avoided sending their children to schools with low rankings on GreatSchools or Niche. And this, according to parents who have chosen to send their children to low-ranked schools, is where the ratings have actually done parents everywhere a disservice.

“The grade-school ratings are heavily based on SPR scores,” says Zoe Rooney, 36, who lives in West Mount Airy, sends her children to Henry, and teaches at Strawberry Mansion High School. “SPR” is the School District of Philadelphia’s own contribution to the ranking industry, the School Progress Report. It provides measures of overall school performance: the percentage of students scoring at grade level on standardized tests, the percentage who are showing improvement in their scores, the school climate, and, for high schools, how many students are college- or career-ready.

“Research has shown that those kinds of standardized academic achievement metrics correlate more strongly to economics than they do to anything meaningful about students and learning and teaching,” Rooney says. “So when we see these kinds of ratings used in a decision-making process, or when a parent says something like, ‘I hear good things about the school, but then I look at their rating and they have something like 60 percent proficiency on the PSSA’” — the Pennsylvania System of School Assessment, the state’s standardized testing system mandated by No Child Left Behind — “what they’re actually reacting to is economics.” And yet, says Rooney, well-off white kids who come into such a school “are going to perform the same as they would at those other schools” that get higher ratings. And indeed, a large body of academic literature warns against using performance on standardized tests as a proxy for quality of education. Many test questions, for instance, assume knowledge that lower-income students may not have been exposed to either in or out of school.

Rooney’s views, she allows, may be influenced by her deep commitment to public education. But her decision to put her child in Henry was also based on experience — namely, her own: “I think having experience in the public schools probably did help in that I am familiar with how hardworking and how excellent most of the teachers are across the district.”

It just so happens that Henry is one of only two schools serving Mount Airy that score above 50 percent on the SPR. That ranking may be due to a recent influx of students from more affluent households; the percentage of economically disadvantaged students from within the school’s West Mount Airy catchment has been dropping since the 2017-’18 school year, from 72 percent to 62 percent last school year.

Rooney had other concerns that steered her toward Henry. One of her children is autistic, which ruled out most charter schools as an option. And, she adds, “My husband and I both felt really strongly that being part of a school community with our neighbors and our wider geographic community was really important.”

This concern for community came up with just about every parent I spoke to for this article. It’s also one of the factors an organization called Integrated Schools advises parents to attend to when making the choice to put their children in an integrating school. Rooney serves on the group’s parent board.

The organization has a majority-Black board of directors, while the parent board is integrated but mostly made up of whites. (Rooney is biracial.) Its message, however, is aimed squarely at affluent white parents, who, it says, “have been the key barrier to the advancement of school integration and educational equity.”

The group’s efforts to increase the number of white and/or privileged parents who “intentionally, joyfully and humbly” enroll their children in integrating schools like Henry begin with changing the language parents use to describe schools. Talk of “good” and “bad” schools, the group argues, contributes to the “smog” of fear that clouds white parents’ ability to see past their own self-centered concerns and instead join in building that “beloved community” Martin Luther King spoke of, one grade school at a time.

Or, as the group puts it, “We are empowered by the belief that integration is not a sacrifice of our own children but rather an investment in the future of all children and the world we want for our kids.”

Leah Hood, one of two Germantown parents who got me started thinking about all this by double-teaming me one Sunday after services at First Presbyterian Church in Germantown, shares that belief and that concern about the language we use to discuss schools.

“There are some really important conversations going on in the neighborhood about the need for us to integrate in a way that is good for everybody, not just by bringing in more white students,” says the 42-year-old white mother of two. “In the past, just the amount of white students has been the marker of whether you’re doing anything right.”

Hood enrolled her children in her neighborhood school, Anna L. Lingelbach, located on the Germantown side of the Germantown-West Mount Airy border. The school has great potential for both racial and socioeconomic integration, since its catchment includes the most affluent part of Germantown. (Yes, there is one; five percent of Germantown households have incomes above $150,000 per year.) It’s also home to many white residents — and of course, West Mount Airy is that famously integrated neighborhood’s whiter and more affluent side.

Yet according to SDP enrollment figures, Lingelbach is 84 percent Black, five percent white, and five percent Hispanic — and 100 percent of its students are economically disadvantaged. Despite that last figure, there’s nothing about Hood that signals deprivation.

She sort of stumbled across Lingelbach as her older son was getting ready for kindergarten seven years ago. Her neighbors hadn’t warned her away from the school, but she got the sense they didn’t consider it an option for their kids. Her concern for equitable school funding, along with sheer curiosity, led her to pay the school a visit right around the time her son was ready to enroll.

“I was pleasantly surprised,” she says. “And I say that with deep embarrassment, because I think that for privileged white people, the fact that we don’t necessarily have to consider that our local neighborhood schools, wherever they are, would be a good option is really part of the problem.

“And it’s an indictment of families like mine, and I felt really aware of that. I had written this school off, and it took me going inside the building to realize it was small, it was really warm, the kids were awesome, the teachers were engaged. And for me, it was like, ‘Wow, this is a place we could actually consider.’” It’s a point that bears repeating: Visiting a school reveals so much more than a ranking does. Just as we wouldn’t buy a house sight unseen, we shouldn’t choose a school that way, either.

“It took me going inside the building to realize it was small, it was really warm, the kids were awesome, the teachers were engaged.”

Hood is frank about how her children would have fared in any city school: “By virtue of who we are as a family, by virtue of the system that we’re all swimming in, our kids are, generally speaking, going to be okay,” she says. But she adds that the teachers at Lingelbach really helped her kids along: “Honestly, it was some of the most masterful teaching I’ve ever seen. I couldn’t have paid any private school to get a better teacher.”

Her sentiments echo an anonymous parent who wrote a review of Lingelbach on GreatSchools in 2015, giving the school four stars and saying her child was “finally getting the support that my $21,000 couldn’t buy him in private school.” Lingelbach gets an overall two out of 10 rating on GreatSchools.

It’s likely that this praise comes as no surprise to Lisa Waddell, Lingelbach’s principal. Now in her sixth year at the school, she came on board after that review was written; her predecessor, whom the reviewer parent also praised, left after one year on the job.

A school district veteran who came up from the teaching ranks, Waddell describes Lingelbach as something of a hidden gem, a diamond in the rough. The stability of its faculty and staff, she says, is one of its strengths. “It’s the kind of school where once a teacher selects Lingelbach, they’re not leaving. Some teachers who were teaching children there, they’re now teaching those children’s children,” she says.

And word is beginning to spread among the neighbors. “I think that oftentimes, there’s a dismissal of the public schools in the neighborhood,” Waddell says. “But over the past two years, we’ve been getting traffic at our open houses from people within the community. That’s been a big shift for us in terms of our school becoming more diverse than in the past.”

She attributes some of the change to younger families who are buying homes in the area. These families, she says, aren’t simply writing off neighborhood public schools as an option for their kids.

This trend is also appearing in neighborhoods far from Northwest Philly’s relatively integrated neighborhoods. For example, consider the case of Fairmount and Francisville, two adjoining neighborhoods in the Bache-Martin school catchment that have witnessed significant influxes of new, younger, whiter residents.

One such resident is Chris Smith, a 44-year-old financial analyst who moved to Fairmount 20 years ago. He loves the neighborhood so much that he bought a house there 10 years ago, before he got married and the thought of children came along.

When Smith’s first child did arrive, about nine years ago, he and his spouse considered several options for after nursery school, including a private school and a specialized charter. “But at the time, there was a huge groundswell of support for Bache-Martin” in the neighborhood, Smith says. That was about the time this magazine ran the infamous cover story “Being White in Philly.” I said then that the story had been mistitled — it should have been called “Fear and Loathing in Fairmount.” Clearly, Smith and his neighbors who were learning about Bache-Martin neither feared nor loathed their neighborhood.

Like Lingelbach, Bache-Martin has been around a while: Its two buildings date to the early 1900s and the 1930s, respectively. (Lingelbach opened in 1957.) And its physical plant was in need of a major upgrade, which it got last year. The school is something of an integration success story: It’s now 53 percent Black, 24 percent white, 12 percent Hispanic, two percent Asian, nine percent multi-racial, and 84 percent economically disadvantaged.

Smith became part of a wave of parents, mostly white, who in around 2013 began fund-raising and pushing the district for support the school needed for both maintenance and educational support. “The staff of the school was solid; the staff of the district, probably not,” he says of the people in charge at the time.

As at Lingelbach, the school’s parent-teacher support group, or HSA, provided crucial support for the school’s teachers and staff. But where Lingelbach’s former HSA consisted largely of Black families who had been in the neighborhood for years, Bache-Martin’s was made up mainly of new white arrivals.

This didn’t sit well with Ashanti Martin, a 42-year-old writer and editor who has two children attending the school. A neighbor and parent at the school asked Martin to run for a position on the HSA board with her, but shortly after she was elected vice president for communications, she decided to leave the board. She pleaded lack of time, but the bigger reason was race fatigue — the strain that accompanies being a Black face in a white space.

“They’re not respecting the cultural differences. They’re basically gentrifying the schools,” she says of the people she served with on the HSA board. “They’re coming in because they want to make the school work for them, and they are sort of imposing their vision of what a good school is.”

And as that board wondered why it had almost no non-white members, Martin was sitting there thinking to herself, “I don’t want to be here, because I feel like an outsider.” She and her white husband, she notes, share the same socioeconomic status and class attitudes as the board members; a lower-income parent would probably feel even more alone.

Ashanti Martin, who has two children at the Bache-Martin school, says affluent parents shouldn’t try to “impose their vision of what a good school is.” Photograph by Linette and Kyle Kielinski

Martin has some advice for affluent parents: Don’t come into a city school like you’re going to colonize it. “You can do the right thing,” she says, “but not until you acknowledge that the school is not there for you.”

Affluent parents in city schools, she notes, will need to deal with things that may make them uncomfortable, like the occasional fight. But, points out Alison Cohen, the 45-year-old CEO of Bicycle Transit Systems and parent of a child at Mount Airy’s Henry Howard Houston School, it’s not like schools in the suburbs are without disciplinary issues. She should know: She’s a product of Lower Merion schools. (Until Kobe Bryant broke it, she held the all-time basketball point-scoring record at Lower Merion High.)

“A white family might go out of their way to be an integrator, and then when there’s a bully or there’s disciplinary issues, it’s easy for them to pull out,” she says. “And you picture that same situation in Lower Merion. There were disrupters and bullies there, but you didn’t see families just pull out over a single incident.

“We view our participation in the Houston community as not something we are just trying on,” she says of herself and her wife, Nurit Bloom. “You don’t just change your mind because something happened.”

Alison Cohen (left) and Nurit Bloom at Henry Howard Houston School in Mount Airy, where their child is enrolled. Photograph by Linette and Kyle Kielinski

The subject of safety comes up frequently in discussions like these, but the Integrated Schools crowd says those fears are overblown. Which is why the group stresses the word “humbly” in describing the attitude white parents should take toward integrating the schools they’ll send their children to.

That may not be all that easy for many parents. As I said at the beginning, if you’re entering an institution or a society as an outsider, you’ll find others calling things you took for granted into question, which can be discomfiting. And if you’re used to being part of the dominant group, the urge to remake the institution in your image will be powerful. But do so, and you’ll miss out on one of the most valuable lessons both you and your children will learn.

If you’ve made it this far, you may wonder where I get off telling you to consider your neighborhood public school for your kids when my own mother sure didn’t. Here’s why: She had a specific goal in mind that you might want to consider, too.

My mom, Estella Frank Davis, grew up in the small Kansas town of Horton. In the years before Brown v. Board of Education, Kansas didn’t require segregated schools; it left the choice up to individual school districts. Horton, which had nearly 2,800 residents in 1940, was too small to segregate its schools. So Mom was a decided minority in her class all the way from grade school through graduation in 1948. She went from there to the University of Kansas, graduating with a B.S. in nursing in 1954. And again, she was in the minority there.

Having gotten educated and then gone to work in overwhelmingly white environments, Mom decided that her son should also learn the ways of white folks, so he, too, could compete with them according to the rules they set — and beat them.

She made the same choices for my brother when he came along nine years later. But by then, Kansas City’s public schools had deteriorated, in no small part because better-off white families had turned their backs on them. My brother attended private school from the time he was old enough to the time he and Mom left Kansas City so she could pursue her career.

The world we face now is different from the one I grew up in during the 1960s. This country has become much more polyglot, especially its cities. Today’s children will come of age in a world where both their workplaces and their social settings will be full of those who are quite different from them, even if they share some things in common. One of the biggest lessons an integrated school can teach is that all of us can learn how to forge new communities that at once honor and transcend our differences. Black families have sought such places out for decades. It’s time the white folks finally caught up with us.

Published as “The Right School for Your Kid … Is Probably the One in Your Neighborhood” in the September 2020 issue of Philadelphia magazine.

Philadelphia magazine is one of more than 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and economic mobility in the city. Read all our reporting here.