Philly Officials and Church Leaders Helped an Undocumented Mom Send Her Kids to School

Carmela Hernandez and her four children have sought sanctuary in a North Philly church for six weeks. Now they’re stepping outside — and defying ICE — to get an education.

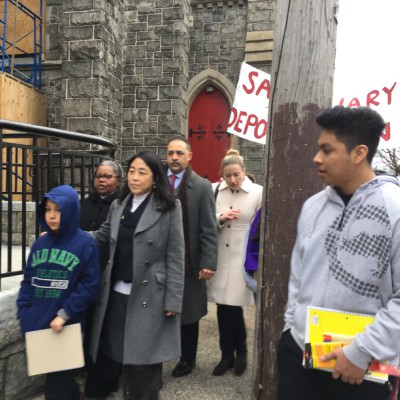

Carmela Apolonio Hernandez stands with her children on the steps of the Church of the Advocate in North Philly.

Church leaders, city officials and community organizers gathered at the Church of the Advocate in North Philly on Monday morning to help an undocumented immigrant mother do what so many other mothers have: send her children to school.

Carmela Apolonio Hernandez and her four children — 15-year-old Fidel, 13-year-old Keyri, 11-year-old Yoselin and 9-year-old Edwin — are under federal order to be deported to Mexico. The family has sought sanctuary in the Episcopal church, where Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers are unlikely to make arrests, since mid-December.

Now Hernandez and the nonprofit New Sanctuary Movement, a grassroots organization that has assisted the family, are sending a clear message to ICE: Her children, like all children, deserve access to an education.

Around 8 a.m. on Monday, the four children – escorted by City Councilwoman Helen Gym and state Rep. Chris Rabb – walked outside the safety of the church, through a crowd of roughly 50 supportive onlookers, and into a minivan. Then they rode to school.

Their choice to do so is a right, according to Gym, Hernandez and Hillary Linardopoulos, a representative for the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers union.

“In the current political climate, so many children are afraid for their futures,” Linardopoulos said at the church on Monday. “It is incumbent as educators to be there and to be witnesses to students’ struggles and to support them.”

The New Sanctuary Movement and church leaders have not said where the Hernandez children will attend school, in hope of protecting them from deportation.

ICE guidelines maintain that officials typically do not make arrests in “sensitive locations,” like schools, places of worship, healthcare facilities or public demonstrations. Exceptions can be made if officers obtain prior approval from supervisors or other law enforcement actions have led officers to the location. The policy is intended to “enhance the public understanding and trust, and to ensure that people seeking to participate in activities or utilize services provided at any sensitive location are free to do so, without fear or hesitation,” per the federal government. But ICE can make arrests anywhere outside these locations, and they can make traffic stops if they suspect a car is carrying undocumented immigrants – and their suspicions are based on more than appearance.

Hernandez, 36, came to the U.S. with her children in August 2015. She has said that organized drug criminals murdered her brother and two nephews – taxi drivers who could not pay extortion fees – then threatened and assaulted her and her oldest daughter, according to the Inquirer. Her request for asylum in the U.S. was denied, and she was ordered to leave the country on December 15th. She says she is appealing the decision and that her family is at risk if they return, but she doesn’t want to force her kids to keep living inside, in constant fear of detainment or deportation.

Gym and Rabb walk the children to the minivan.

“They are children,” Hernandez said at the church, speaking in Spanish. “For them to be cooped up in a room is hard.”

Hernandez remained inside the sanctuary on Monday while Rabb, Gym and several others led the children outside.

Gym said she wanted to send a message to ICE that “this family is loved and welcome here in our city” – and that the children “have the right to go to school, come home and feel safe on these streets.”

The situation is sure to increase existing tension between federal authorities and Philly, a so-called sanctuary city that has already gone to court against the government over its immigration policies. The family’s decision brings into the conflict the Philadelphia School District, which maintains that students are entitled to an education regardless of immigration status and upholds federal law that prohibits school staff from disclosing student information, including to federal agents. Neither ICE nor the school district immediately returned requests for comment on Monday.

“We want to be free,” Hernandez said on the church steps. “We want to be permanently free.”