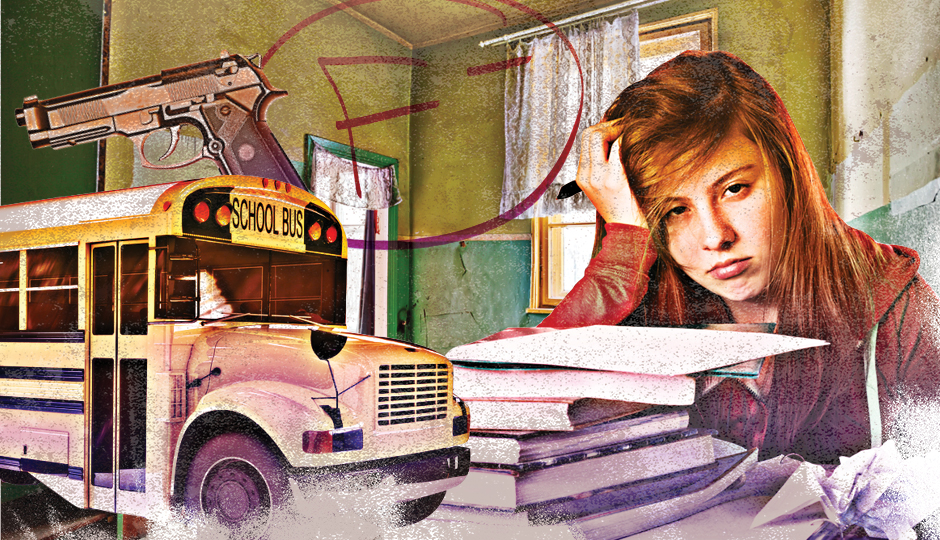

How Trauma Overwhelms Philly Schoolkids

Photo illustration | Alyse Moyer. Photos | Shutterstock.com

During the 18 years he was a counselor at Barratt Middle School in South Philadelphia, Steven Hymans became accustomed to seeing students arrive for classes traumatized beyond their years.

“There were so many homicides in the neighborhood,” Hymans said recently. “In my 18 years at the middle school, I saw a lot of trauma, a lot of neglect. I did so much grief counseling while I was there.”

The kids who came to school having witnessed violence — a relative shot, or a robbery, perhaps — often found it a bit more difficult to settle down and study, Hymans said. Many showed symptoms of “hypervigilance,” a common symptom of post-traumatic stress disorder. “You can see the instability is difficult for them,” he said, “and stressful.”

Hymans’ story apparently isn’t uncommon: Using national rates as a guide, officials estimate at least half of Philadelphia school students have experienced one major traumatic event. At least one-fifth have probably experienced two or more such events.

Do the math, and that means as many as 60,000 Philadelphia students are coming to school having experienced trauma that has the potential to upend their lives, their schooling, and their future.

“The research shows that there’s these repeated traumas coming into the schools,” said Jody Greenblatt, who oversees school climate matters for the district.

So Philadelphia School District officials are preparing to do something about it. Deep inside the new “Action Plan 3.0” unveiled earlier this month by Superintendent William Hite is a brand-new directive: Teachers and staffers in the district are going to learn how to recognize — and help — thousands of students experiencing trauma.

“Kids that experience repeated trauma are in fight-or-flight stance all the time,” Greenblatt said, explaining the classroom effects. “It can be anger, withdrawal, quick temper.”

Why It Matters

The good news? Researchers and academics in Philadelphia appear to be on the forefront of “trauma-informed” practices to help ground such students and help them complete their studies. The city hosted the first National Summit on Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) in 2013; in 2014, the Health Federation of Philadelphia won a grant to help develop community-level efforts to build trauma-informed care nationwide.

Kevin Dow, senior vice president of Impact and Innovation at United Way of Greater Philadelphia and Southern New Jersey, says the trauma can literally reshape the young brains of school-aged children, enlarging that portion of the brain that scans for threats.

“Children experiencing this type of toxic stress are unable to access the executive functioning area of the brain,” Dow said via email. “Without access to the cortex, children have difficulty or are unable to learn in the same way.”

Is it possible for a child to live in Philadelphia and not eventually come to school traumatized?

“Some urban stress” is tolerable and doesn’t trigger a stress-response for a child,” Dow said. “But, trauma leaves children feeling helpless, hopeless and even ashamed. This kind of toxic stress affects the child’s brain, has implications for the future of the child, and academic performance can suffer.”

Already, Greenblatt said, the district has for two years offered teachers courses — funded through the United Way — on how to recognize when students are experiencing trauma and how to help them calm down and recover enough to be effective in the classroom. There’s room for just 15 teachers and administrators in each class, she said.

The response to those classes? Overwhelming.

“Those classes have been full. People register the first day it’s posted,” Greenblatt said. “Hundreds of teachers and principals have taken them so far

Dow said a wider approach to dealing with trauma in Philly schools will involve helping teachers recognize when to give students space and time to calm down — Greenblatt said sometimes getting a child a drink of water and giving them 20 minutes to “reset” is all that’s needed — and helping them see how not to accidentally trigger a fresh round of trauma in the child

“When teachers are trauma-informed, they understand that in order for students to learn, their brains need to be in a calm and regulated state.” Dow said.

Hite’s “Action Plan” doesn’t offer a timeline for putting resources into place, nor an estimate of what it might cost. If the good news is that Philadelphia is better prepared to assist such students, though, the downside is this: The city may also create more people in need of those services. “We know,” Dow said, “that Philadelphia’s trauma rates are much higher than national rates.”

And that means Philadelphia schools face a greater challenge, Greenblatt suggested: “I think in any urban environment,” she said, “there’s going to be a greater number of traumas.”

Follow @JoelMMathis on Twitter.