Does Handwriting Really Matter?

A reduced focus on penmanship threatens the learning and creativity of our students.

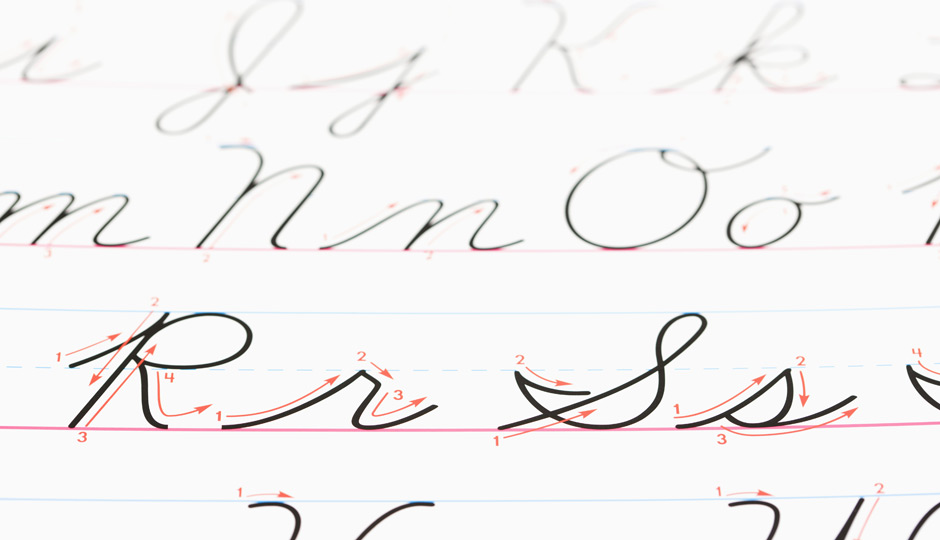

Shutterstock.com

As a product of Catholic school education, it’s hard for me to imagine a world where good penmanship doesn’t matter. In fact, I still remember a day in sixth grade when I was instructed to re-write a cursive letter “D”’again and again because I opted to put my own personal flare on the old-fashioned stencil. Aside from the personal trauma that comes with overzealous instruction from ladies dressed in habits, there’s a different kind of psychology associated with handwriting, according to a piece in the Times.

“Children not only learn to read more quickly when they first learn to write by hand, but they also remain better able to generate ideas and retain information,”the story goes. “In other words, it’s not just what we write that matters — but how.”

The point holds for grown ups, too. In a mobile world of synced calendars and iClouds that hold all the things we hold most dear, writing things down often makes life’s details easier to remember — even if technology makes it all quicker to recall.

And if technology enables us to spend less time thinking, so we’ll have more time for doing, it’s no wonder we spend less time strengthening the creative muscles in our brain. Double-click culture has shifted the way we consume words, shortening our attention span, which undoubtedly stymies creativity. We don’t even have time to read. After all, it is the Internet that is responsible for the primacy of the “listicle,” and for the fact that articles online (even the think pieces!) rarely top 800 words.

For writers, technology enables us to do things — including thinking — quickly, but perhaps we are not as thoughtful as we might be if we were forced to think at the speed that we write.

“With handwriting, the very act of putting it down forces you to focus on what’s important,”psychologist Daniel M. Oppenheimer of the University of California,Los Angeles, said in the Times piece.“Maybe it helps you think better.”

It sounds strange, but when I think about my students at Mighty Writers, this tends to ring true. The few who do write in cursive tend to be better writers, or at least more imaginative ones. Those who print clearly (especially if their handwriting appears a bit smaller and more methodical) also tend to churn out interesting and fresh ideas when given assignments.

The problem with technology is that sets up the potential that everything is important because everything is right now. Alerts crash into our phones at all hours of the day, reminding us that someone, somewhere is awake and curating more content to get our attention. More things for us to buy. More dates to save. More meetings to schedule. More. More. More. If writing was first intended to document the occurrence of things for the preservation of memory, what does this mean in a culture that is fixated on living in the perpetual now. Will technology, like photography, render words obsolete in time?

But it’s so much less, too, especially for those who don’t remember a world without it. In classrooms, college (and even some high school!) students have replaced spiral bound notebooks for Mac notebooks. Surely, this impacts the quality of learning and discussion that students participate in (especially if one is Google chatting while note taking). The text message is replacing the older technology once known as a phone call. Less remembrances. Less connectivity. More touch and go. More autopilot.

And what is to become of the next generation of novelists? Will the stories they tell become less engaging because they didn’t focus on handwriting? According to research done by Pew, some educators feel that digital tools have blurred the lines between formal and informal writing and have made it harder for students to understand voice and audience. Plus, the “cultural emphasis on truncated forms of expression … [hinders students’] willingness and ability to write longer texts and to think critically about complicated topics.”

So, will the things we read all start to sound the same? Are all slowly becoming part of the same collective audience, eager to be a part of something but without enough space, time or interest to think about what that really means? There are still an abundance of purists among us – people who won’t go anywhere near an e-reader; those who write measuredly in notebooks and jot notes on loose pieces of paper. Perhaps they’re the ones to with enough discipline to record us as we really were, in hindsight, not just in the moment.

Follow @MF_Greatest on Twitter.

Previously: Sandy Hingston’s “The Death of Handwriting”

Previously: Joel Mathis: “Let’s Just Let Cursive Writing Die Already“