History: The Missing Lincoln

Was Honest Abe suffering from a rare fatal disease? A bloody pillowcase holds the answer — if a dusty Northeast Philly museum will give it up

THE WORST HAD happened.

First had come the noise, the shot, the terrible commotion in the theater across the street, before the nice young man who rented the front room threw the doors open and shouted into the mayhem: “Bring him in here!” The grim men trooped in, and the doctor came running; the wife and son sat sobbing in the front parlor, and he lay in the back room, dark and gaunt, so tall he could only fit diagonally on the bed. More grim men assembled, talking in low voices. One sat and sketched the scene. All Anna Petersen could think was Please God don’t let him die; she whispered it again and again as she brought hot water and toweling. The doctor fished for the longest time for the bullet; how could any soul survive such poking about? The night wore on, and the thin dawn came, and his breathing was slower and harsher, until finally they said: “He is dead.” They carried him out, and there was nothing left but the mess made by boots and tobacco and teacups, and the disheveled sheets, and the pillow stained with blood from the hole in his head.

She didn’t know where to start. So she began with the bedclothes, bundling them up tightly, and went to toss them into the gutter, wishing she could strip away what had happened that easily. But then she heard a voice: Hermann Faber, the young man who’d been sketching. He reached out a hand.

“Could I … ” He gestured to the pillowcase. “May I have a piece? Please?”

She cut away a small strip and gave it to him. “Now he belongs to the ages,” Secretary of War Edwin Stanton had told President Lincoln’s inconsolable widow.

The bit of pillowcase did, too.

THE GRAND ARMY of the Republic Civil War Museum and Library looms up out of a hinterland of Frankford rowhomes like Princess Di in Calcutta — a tall, elegant aristocrat surrounded by decay. The front door of the Georgian brick mansion is almost always locked; you enter through the rear, past backyards clogged with trash and cast-off toys. There isn’t much parking, but that’s okay, because hardly anybody ever comes here. The Grand Army of the Republic Museum is only open on the first Sunday of each month and on Tuesdays from noon to four, but call first, because it might not be. Still, “If a neighbor kid knocks while we’re here and asks, ‘Is this a museum?,’” says Eric Schmincke, president of the board of directors, “we’ll show him through.”

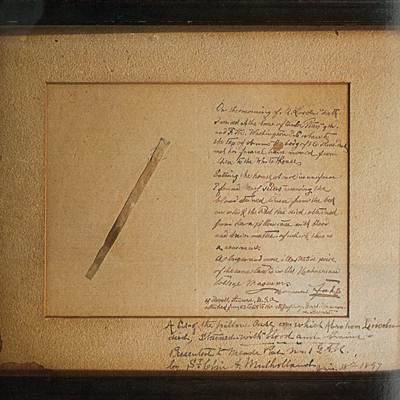

Inside, the museum has lots of old stuff laid out on shelves and hung on walls and resting in heavy wood-and-glass cases: the handcuffs John Wilkes Booth planned to use to kidnap Lincoln; a maquette of Philly’s own General George Meade, commander of the Union troops at Gettysburg; a shingle from the house where Lee surrendered to Grant. Visitors used to wander on their own amidst the memorabilia, but now someone is always posted downstairs, because that’s where the museum keeps its treasure: the scrap of pillowcase Hermann Faber begged from Anna Petersen in her house across from Ford’s Theatre on the morning Lincoln died.