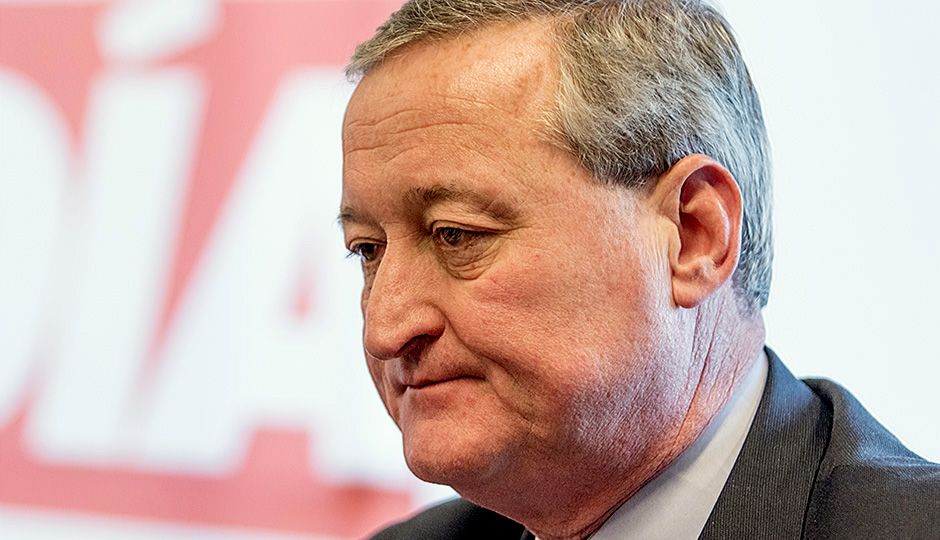

Is Jim Kenney a True Progressive?

True progressive? | Photo by Jeff Fusco

Like a good Catholic boy, City Councilman Jim Kenney was attending mass in South Philadelphia.

Unlike a good Catholic boy — at least as far as the Vatican was concerned — Kenney was supporting a bill to extend partner benefits to gay city employees.

It was the 1998, shortly after “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” was instituted and long, long before a ban on gay marriage was declared unconstitutional in Pennsylvania. Philadelphia Archbishop Anthony Bevilacqua was furious with Kenney, and threatening to hand out voter’s guides to nearly 300 parishes in the upcoming year when he was up for reelection. Kenney’s fellow churchgoers were angry, too.

“Having received communion, I had the host in my mouth,” says Kenney of that day in church, “when a guy came back from communion with a host in his mouth, and started, through clenched lips, trying to give me a hard time” about the issue.

Laughing, Kenney says, “I just pointed to my mouth and said, ‘I can’t talk right now.'”

It’s a funny story, but Kenney, one of three frontrunners in a close mayoral race, isn’t telling it to make me laugh. He’s trying to make a point: He was willing to take hits from guys in the neighborhood as well as the Archbishop himself for LGBT rights.

“It was a real foray into showing people what I was about, what I cared about, and how I was willing to take tough positions sometimes that weren’t necessarily politically beneficial to me,” says Kenney. “I knew I was doing the right thing.”

Whether he wins the mayor’s race may depend on whether he can prove to voters that he sticks to his guns on liberal issues that matter to him. Kenney needs progressive voters to turn out, and he needs them to vote overwhelmingly for him. That’s his only path to victory. Now, though, his opponents are painting him as a Jimmy-come-lately to the progressive cause, and they’re dredging up incidents and votes from Kenney’s long career that cast doubt on his progressive credentials.

State Sen. Anthony Williams just a launched a new anti-Kenney website that reads, “What Jim Kenney says now that he’s running for mayor of a progressive city and what his record says about the 23 years he’s spent as a Fumo machine operative, are very different things.”

It goes on to detail his opposition in the 1990s to both an independent police corruption commission and limitations on the use of force by police officers. Contrast that with the Kenney of today, who is known for being a vocal critic of the city’s stop-and-frisk policy, the War on Drugs, and the cooperation between city police and immigration authorities.

Former city solicitor Nelson Diaz‘s campaign, meanwhile, has been whacking Kenney for months now, saying that he “needs to account for what he once proudly called a ‘moderate-conservative’ Council record that only ends curiously close to his decision to run for mayor.”

Are Kenney’s opponents right? Has he only jumped onto the progressive bandwagon to win this election? Should progressives trust him?

It seems clear that the Kenney of the 1990s and early 2000s took positions that are in clear conflict with the views he holds today. Consider the fact that:

- In 1993, Kenney voted against a bill banning military-style assault weapons. “It gives people a false level of comfort that somehow the passage of the bill removes guns used in the commission of crimes,” Kenney said at the time. He was one of only two Council Democrats to vote against the bill. Lauren Hitt, his campaign spokeswoman, says that the the city lacked the authority to enforce a gun ban, and he believed Council wanted to simply appear as if it was fighting violence, though it really wasn’t. “He later voted for such a ban in 2008,” says Hitt, “because after the state legislature became increasingly aggressive in its anti-gun control legislation, he realized it was more important to send a message to Harrisburg than to Council.”

- In 1996, Kenney supported the creation of a pilot voucher program, which would give public dollars to parents that they could use to send their children to private and parochial schools. Today, he is a staunch opponent of vouchers, and has the backing of the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers. “As my style of clothing has changed since 1996, so has my evolution and understanding that vouchers are no longer a viable option,” he says.

- As Williams’ site rightly notes, Kenney opposed the creation of an independent commission to investigate police corruption in 1995. “How many commissions do we need?” he asked at the time, noting that the U.S. Attorney’s Office, FBI and Police Advisory Commission could examine police wrongdoing. The liberal wing of Council backed the commission; the conservative wing did not. Today, Hitt says he would support such a panel. She explains, “There is increased distrust between the community and the police, with a handful of bad officers ruining the reputation of so many good ones, and it’s important that the city send a message that it’s serious about rooting out those bad officers.”

- Kenney, a graduate of St. Joe’s Prep, said he would not back a proposed college scholarship program in 2003 unless it was made available to parochial students. “I find it to be very arbitrary and unfair that this program … discriminates against our parochial school students,” Kenney wrote to then-Mayor John Street. Today, Hitt says, “If it was a choice between no scholarship program or one without parochial students, he would vote for the latter.”

In the 1990s, Kenney himself called his record “moderate-conservative,” and complained that the “liberals” on Council were blocking his proposals to ban “aggressive panhandling” and prevent homeless people from sleeping in Philadelphia’s business district.

But even in those more conservative days, Kenney was out front on gay rights, as well as initiatives to bring more immigrants to the city. One could argue, perhaps, that he was inching toward progressivism.

Regardless, since the mid-2000s, Kenney appears to have altogether abandoned the “moderate-conservative” side of the political spectrum. Most, if not all, of the examples of Kenney’s hypocrisy cited by Williams and Diaz are at least a decade old.

In more recent years, Kenney has voted for “ban-the-box” legislation, which bars employers from asking about a person’s criminal record on job applications. He fought for a law that would require city government to pay for transgender employees’ surgeries. He introduced groundbreaking LGBT rights legislation, which offered a tax credit to businesses that provide the same benefits to gay workers in domestic partnerships as they do to straight married couples.

He is also responsible for introducing the bill that decriminalized marijuana in Philadelphia, which he calls one of his proudest moments in Council. “It was common-sense legislation, but it required taking on Nutter and the police commissioner, which aren’t easy obstacles to get around, but we did it,” he says.

Plus, he backed the creation of the Board of Ethics, co-sponsored a bill to allow undocumented workers to obtain city IDs, and called for the police department to stop cooperating with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement in certain circumstances.

So why are these old votes and positions still dogging Kenney’s campaign?

It may be partly because of his relationships with two of the most powerful kingmakers in Philadelphia’s history. Kenney was schooled on politics by the disgraced former state Sen. Vince Fumo, and he is now being backed in the mayor’s race by electricians union boss John “Johnny Doc” Dougherty. Kenney argues that he cut ties with Fumo long ago, and that Doc, much like himself, has changed in recent years. But no matter how you slice it, Fumo and Doc are not exactly darlings of the progressive movement, and Kenney will forever be associated with them.

Another reason Kenney’s past record has come back to haunt him, perhaps, is because Kenney hasn’t offered a dramatic, easy-to-understand explanation for his evolution from proud moderate-conservative to a proud progressive. He says it was simply a slow, steady process inspired by his more liberal former colleagues on Council, such as Angel Ortiz, Marian Tasco and the late Augusta Clark. There was no epiphany. No lightbulb moment.

“It’s a 25-year-journey of maturation and learning and being tutored,” says Kenney. “When I came into Council at 32 years of age, I thought I knew everything and I really didn’t. It’s like one of those situations where your parents are really dumb when you’re 13, and the older you get, the smarter they get. Well, the older I got, the smarter I got.”

And Kenney is adamant that he’s not looking back.

“Do people really think I would flip-flop back to being Frank Rizzo?” he asks. “Been there, done that. It wasn’t fun. It wasn’t good for the city, and the city’s come a long way since. I don’t see why anybody would think I would immature back to where I was 25 years ago.”

Other Highlights from Kenney’s Council Record:

- Kenney sponsored a bill in 2001 that would have capped annual campaign contributions at $1,000 for individuals and $5,000 for PACs. Council voted against it 10-7.

- During the 2007 mayoral race, Kenney introduced legislation that would eliminate campaign contribution limits if a candidate spent more than $2 million of their own money during an election. It was not successful.

- In 2009, Kenney introduced legislation that would require cyclists to obtain license plates and raise the fine for biking on sidewalks. It didn’t go anywhere.

- In 2010, Kenney proposed suing Facebook, Myspace and Twitter if authorities found evidence that teens organized a flashmob on the social media sites. The city did not do so.

- Kenney proposed a bill in 2011 to bar restaurants from deducing credit card fees from workers’ tips. It passed.

- Kenney sponsored a bill in 2013 to make the city’s Office of the Inspector General permanent. However, it did not give the Inspector General the authority to investigate Council. It was not approved by Council.