Jack Bogle and Vanguard’s $5,000,000,000,000 Question

As the once-scrappy Malvern company approaches $5 trillion in assets, even founder Jack Bogle has to wonder: Has Vanguard simply gotten too big?

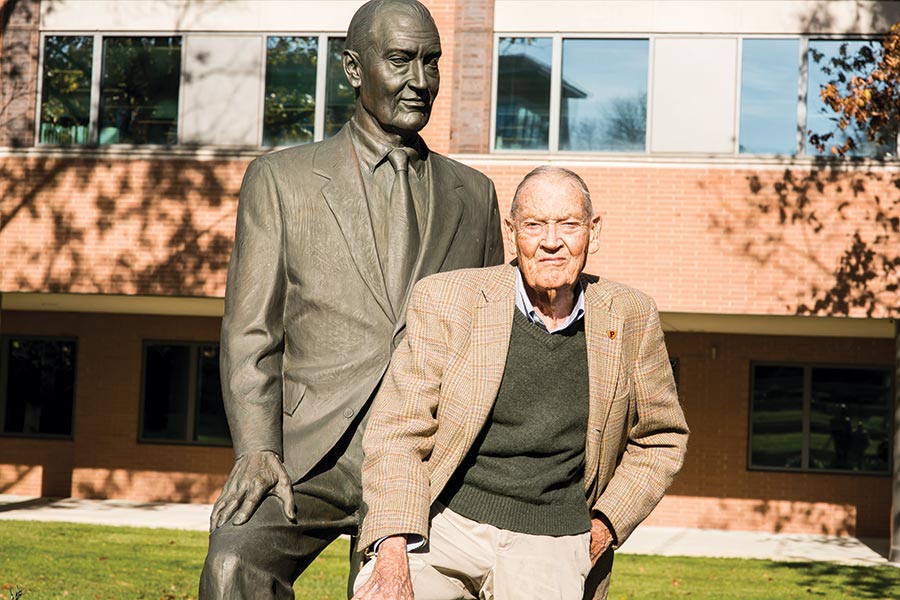

Jack Bogle | Photograph by Adam Jones

Rare is the man whose form and visage have been captured both in a larger-than-life-size bronze statue and a six-inch-tall plastic bobblehead doll. John Clifton Bogle is one of them.

As living legends go, Bogle is a modest fellow, or at least he tries to be. “Call me Jack” is his normal conversation starter. He’s old-fashioned, even for an 88-year-old — the kind of guy who has simple rules for living a good life, codified in the aphoristic style of one of his heroes, Benjamin Franklin. “To be called an 18th-century man is to me the ultimate accolade,” Bogle has said.

Rule number one is, “Get out of bed in the morning.” And at the age of 88, most mornings Bogle drags himself out of bed in a far-from-palatial stone house in Bryn Mawr, dons an outfit straight out of the Preppy Handbook, says goodbye to Eve, his wife of 60 years, and then, since he stopped driving a few years ago, waits for one of his co-workers to give him a lift to the office.

Where that drive to work takes him presents a constant challenge to someone trying to maintain a veneer of humility: to the bucolic 220-acre corporate campus that serves as the headquarters of the Vanguard Group, Inc., which began as a 28-person investment outfit headed by an intense, crew-cut, 45-year-old Jack Bogle in 1975. Bogle based the company on an innovative product he’d invented, a mutual fund that left out the usual highly compensated stock-picking manager and simply bought shares from all 500 companies that made up the Standard and Poor’s Index (and therefore became known as an index fund). At first, he struggled to attract a little more than $10 million from underwriters.

Lately, on average, investors have been pouring more than a billion dollars into Vanguard every day.

This fall, Jack Bogle released an updated version of his primer, The Little Book of Common Sense Investing. First published a decade ago, it is one of 11 books he has written (the 12th, his own history of the company, is in the works) and according to the author has sold about 250,000 copies. In it, Bogle sets out his fundamental ideas on successful wealth accumulation for the average person: Invest in indexed mutual funds mixed between stocks and bonds, and hold onto them. Bogle is convinced — and he has done lots of research to support his case — that it’s almost impossible to beat the market over the long run, and that “average” returns combined with low management expenses and fees (which Bogle made sure were the core of Vanguard) are the best deal for investors.

“From almost the first day of Vanguard,” Bogle tells me in a recent interview, “I’ve seen so much of this industry and so many phony funds and so much money pouring in when your performance is hot and pouring out when your performance is cold. That’s not a very good way to make money. The first thing I demanded is that we were going to have funds with relative predictability.”

It has taken decades, but what was once called “Bogle’s Folly” — a so-called “passive” approach to investing that buys and holds a widely diversified basket of stocks representing a broad portion of the market as a whole, rather than one that tries to pick winners — has become certifiably trendy. We appear to be experiencing a rare outbreak of the contagion of common sense.

“In the last 10 years, investors have put around $2 trillion into index funds,” Bogle reports. Yes, that’s trillion. Other companies offer index funds, but Vanguard has long dominated the market. “Since January 2015,” Bogle adds, “Vanguard has taken in a cool $793 billion. The entire industry has taken in $815 billion. It’s amazing.” By the end of 2017, the house that Jack built was on track to have $5 trillion in assets under management.

Jack Bogle started Vanguard in difficult personal circumstances. He’d been fired from the top job at a money management firm called Wellington (the founder had handed him control when he was 38) by the very partners he’d invited to join the firm. Something of a sailing buff, he picked his new company’s name as a reference to the flagship of the famous Admiral Lord Nelson. Nautical touches have long been a staple of the company culture. Now, as he goes to work each day at the four-person outfit known as the Bogle Financial Markets Research Center, which Vanguard set up for him as consolation for adhering to the company policy of 70 as mandatory retirement age, the original little skiff of a company has grown into a giant money supertanker.

Bogle is in a peculiar situation so late in life. After he’d staked his career and reputation on an untested notion that was the financial world’s version of sailing against the wind, the wind reversed. Now he’s lionized as a financial sage, and the company he started has grown and prospered beyond anything he might have imagined when he reluctantly handed over control two decades ago. Yet he’s unable or unwilling to quell his contrarian nature and a strong moralistic streak, and he can’t help but question whether Vanguard is shipshape to weather its own phenomenal success.

Is big better?

“To be absolutely blunt about it, it doesn’t do a lot for me,” Bogle insists. He has the craggy looks and doctrinal fervor of a preacher out of Hawthorne, with a playful side that leaves open the possibility that he’ll drop an off-color joke into the middle of his sermon. “I told people that I never had any interest in building a colossus. But I was too damn stupid to realize that if I gave investors the best deal they would ever get, I would build a colossus. So that’s what happened.”

The company now employs about 15,000 people (who are called crew members) and besides its Malvern headquarters has offices in three other U.S. cities, with 13 more scattered worldwide. It has become Earth’s largest mutual fund company and the second largest investment company of any kind when measured by total assets managed — and looks to be rocketing toward first place in that category at warp speed. As it has grown over the past four decades, the company has cultivated its image as a big, friendly giant, benign and perhaps a little sleepy.

The unique ownership structure that Bogle set up makes Vanguard the only mutual fund company in existence that actually is mutual — ownership is technically in the hands of the investors, who now number about 20 million. (I’m one of them.) Like all money-management companies, Vanguard charges its investors fees, but Bogle’s other big idea from the beginning was that more passive investing would translate into much lower fees. On average, Vanguard charges about a seventh of what it costs to invest in actively managed funds. Bloomberg estimated in 2015 that every year, Vanguard sucks off $20 billion from Wall Street middlemen.

Actively managed funds can often end up costing about two percent of assets annually, between paying the managers and the expenses charged by middlemen in trading transactions. Many index funds cost a fraction of that — as little as .04 percent, or what the financial industry would call “four basis points.”

“If the market return is seven percent, the active manager gives you five after that two percent cost, and the index fund gives you 6.96 after that four basis-point cost,” Bogle recently explained to the podcast Freakonomics. “You don’t appreciate it much in a year — but over 50 years, a dollar invested at seven percent grows to around $32, and a dollar invested at five percent grows to about $10. Think what an investor thinks about when he looks at that number. He says, ‘Wait a minute! I put up 100 percent of the capital, I took 100 percent of the risk, and I got 33 percent of the return.’ Well, anybody that thinks that’s a good deal, I’ve got a bridge I want to sell them.”

Bogle has always been frugal personally, and the company he built has often been characterized as “penny-pinching.” “They’re famously cheap,” says Kerry Pechter, a former Vanguard employee who still observes the company closely as the editor of Retirement Income Journal. “The place is infused with the idea that money is the investors’ money. You don’t want to be seen throwing away a perfectly good sheet of paper. Wasting shareholders’ money is tantamount to theft.”

Jack Bogle set the tradition that executives only fly coach class. “I started making $100,000 a year in 1974,” he tells me. “It wasn’t bad, but it wasn’t hedge-fund kind of money.” He recalls taking a pay cut in the early days to keep expenses down.

“Once you get big,” Bogle says now, “you start thinking of things in different terms.” For top management these days, Vanguard “has very high compensation levels,” the founder reports. “Which are not disclosed,” he adds. “They won’t even tell me.” Not long before chief executive William McNabb announced that he was stepping aside and passing the CEO job to 25-year veteran Mortimer “Tim” Buckley (who has a degree in economics and an MBA from Harvard and started as Jack Bogle’s assistant), Bloomberg estimated McNabb’s salary in the $10 million to $15 million range.

Still, while two members of the family that founded Vanguard’s onetime arch-rival investment company, Boston-based Fidelity, are on the Forbes list of billionaires and some of the richest people in their home city, Jack Bogle told Freakonomics that his net worth didn’t approach $100 million. “They laugh at me,” he said.

Two months before he was scheduled to take charge of Vanguard this January, Tim Buckley was interviewed at an investment conference in New York. He was asked by a sophisticated money manager the question that would be foremost in a sophisticated money manager’s mind: Will there come a day when Vanguard changes its ownership structure so the top managers can become insanely rich? No, Buckley insisted. “To run Vanguard,” he said, “you have to be willing not to be a billionaire.” Such are the sacrifices of success in a company built on the principles of an 18th-century man.

Bogle today on Vanguard’s campus with his bronze likeness. Photograph by Adam Jones

The big bronze statue of Jack Bogle that stands amid a grassy courtyard outside the Vanguard corporate cafeteria (which, of course, at Vanguard is called “the galley”) was commissioned when it didn’t look like the man himself would be around long to bask in the honor. After decades of health problems caused by a congenital heart defect and at least a half dozen full-on heart attacks, Bogle was at the point where only a heart transplant might keep him alive. He got on the waiting list for Hahnemann University Hospital’s transplant program, and because his poor health prevented him from following his fundamental dictum to get out of bed every day, in the last months of 1995 he set up a de facto office in a hospital room while waiting for a new heart.

Early in 1996, he received the heart of a 26-year-old, and after he recovered from the surgery, he started to feel 40 years younger. His doctor declined to give him any more specific information about the donor. But Bogle — the kind of guy who had made a habit of answering every letter he received from Vanguard customers — arranged to have a thank-you letter delivered to the donor’s family. He never heard anything back.

The rejuvenated Bogle was back in his Vanguard office by mid-April, no longer CEO but still chairman. Investor money was pouring into Vanguard at an impressive rate (though the dollar figures seem almost quaint in comparison to today’s). In May of 1996, assets under management topped $200 billion. The well-known author and Wall Street Journal investing columnist Jason Zweig was then a young writer for Money magazine. He wrote a story about Vanguard around that time, and recalled recently that to him the company seemed like “a cross-pollination between a guerrilla army and a religious cult.”

“You kind of had to drink the Vanguard Kool-Aid,” a former employee told me. “In a lot of ways, it was boring. The main thing was preservation of the brand and not to do anything to screw up the beautiful thing.”

Jack Bogle often told an anecdote about his company growing to the size where he realized he needed a human resources director. When asked what his hiring policy was, Bogle said, “Hire nice people. And make sure they hire nice people.” While the founder could be genial and personable — the kind of guy who knew all his employees’ names — he was also a hard-driving perfectionist who insisted on proofreading his annual letter to shareholders himself. According to a 1997 history of Vanguard by business journalist Robert Slater, “‘Catch those mistakes,’ [Bogle] admonished his staff repeatedly.” Bogle’s son, John Jr., told Slater that when they built a treehouse in the backyard, his father insisted it be “done with a high degree of precision.”

But there were definitely benefits to joining the guerrilla cult. “The compensation wasn’t great coming in,” the former worker told me, “but they assured you that the total package would be great.” Vanguard contributed at least 10 percent of an employee’s salary to his or her retirement fund, and it wasn’t unheard-of to glean an annual profit-sharing bonus of 30 percent. “It was a wonderful living,” the former worker said. “It was a great place for people who wanted to live on the Main Line and raise kids. The only dark side was that you needed a thick skin, because the pressure not to make any mistakes was obscene.”

Bogle would be forced to leave his company a few years after his heart transplant, when he reached the company’s mandatory retirement age. “I thought they would make an exception for the founder,” he would say later. Though the principals have never talked in detail about the circumstances, Bogle obviously did not go gently. “What followed,” he says now, “was not the happiest experience of my life. Very strange things happened.” By the end, his handpicked heir, Jack Brennan, a Dartmouth grad who’d been groomed for the top job for years, wouldn’t speak to him or look him in the eye.

Bogle was put out to pasture, but he was hardly willing to retire. He changed tack and began a second career as a prolific writer and speaker, relishing the role of prophet and chief evangelist for indexing. He was now an army of one, and his cult grew and grew.

“If anybody deserves a statue, it’s Jack,” says Mel Lindauer, who is credited with being one of the founding fathers of the Bogleheads, a loosely affiliated group of devotees to Bogle’s investing philosophy of simplicity, diversification, speculation-shunning, and a long-term perspective that the aphorism-inclined Bogle calls “Stay the Course.”

Lindauer is a Kentucky native who ended his stint in the Marine Corps with a posting in Philadelphia. He left the service but stayed in town, starting a graphic design company. As his company prospered and he began investing money, he says, he made every mistake you could. Then he discovered Vanguard and Bogle’s principles. As he headed for retirement, Lindauer started spending more time in Florida and more time online, participating in discussion forums hosted by the mutual-fund rating company Morningstar.

One forum had become a hangout for proponents of low-fee, indexed mutual funds, and they were soon labeled the Bogleheads. Members decided to own the nickname and asked Morningstar to give them their own forum page, eventually breaking off to create their own site, Bogleheads.org.

“The thing has taken on a life of its own,” Lindauer says. “‘Bogleheads’ was once a derogatory term. Now we’ve trademarked it. There are 70-some local chapters and four foreign. The chapter in Dubai has 1,500 members.” The Philadelphia chapter has nearly a hundred.

“People are posting on our site from all over the world,” Lindauer tells me. “We get about 1,500 posts a day, and about four million hits. There are usually between 70,000 and 90,000 unique visitors every day. The numbers are mind-blowing.” And, he makes sure to add, “Vanguard acknowledges that we send a lot of business their way.” Though the discussion threads on Bogleheads.org cover a wide range of issues and often wander into the dense thickets of money management, a common theme in readers’ comments is reverence for Jack Bogle’s fundamental investing philosophy and how well it works for the average person. He is often referred to as “Saint Jack.”

The Bogleheads became so influential that in 2005, Jack Bogle’s publisher, John Wiley & Sons, approached Lindauer and his co-founder, Taylor Larimore, to write a book called The Bogleheads’ Guide to Investing. Then the publisher proposed producing Jack Bogle bobblehead dolls to send out with review copies, as a marketing gimmick.

“I told them, ‘I don’t know. Jack might think it’s disrespectful,’” Lindauer remembers. “But Jack said it was okay as long as they weren’t sold and were only used for book promotion. Then when they came out, Taylor and I got 20 each, but Jack got a ton of them. He used to give them out to Vanguard employees. Now they’re like hens’ teeth — you see them get auctioned off for $1,500. I gave one to each of my grandchildren and told them, ‘If you ever are down-and-out and really need to get some money, put this sucker for sale on the Internet, and don’t take less than a thousand dollars.’”

In October, more than 200 Bogleheads paid $275 apiece and traveled from all over the country to gather in a Philly hotel conference room for three days of communal idolatry of their hero. “I happen to be working on some presentations for the Bogleheads,” Jack Bogle told me when we talked a week before the gathering, which was marking its 16th year. “They are 225 dedicated souls. I go and talk to them for something like three hours. I don’t know how they can listen to me for that long.”

For this year’s talk, Bogle and his research assistant prepared a deck of 72 slides that showed how the indexing idea was being proven right and Bogle was being recognized as a pioneer and sage. There was a slide with a quote from the famous oracle of Omaha, Warren Buffett, from his widely followed annual letter to investors in Berkshire Hathaway. “In his early years,” Buffett wrote, “Jack was frequently mocked by the investment-management industry. Today, however, he has the satisfaction of knowing that he helped millions of investors realize far better returns on their savings than they otherwise would have earned. He is a hero to them and to me.”

There was a slide with the Forbes list of the 100 greatest living business minds, upon which Jack Bogle joined a roster that ranged from Buffett to Oprah. And perhaps to disprove the old adage “Never a hero in your own hometown,” Bogle slipped in a slide with an Inquirer story naming him one of six icons of Philadelphia business, along with the likes of Brian Roberts and Joe Neubauer. “Maybe there was a little too much ego and pride,” Bogle would concede after the presentation. “But it was my year, and I thought, ‘Hell, why not brag about it?’”

The presentation was full of slides with praise from the financially famous for Bogle’s brainchild — the index fund — including a quote from Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Samuelson, whose introductory textbook Bogle read in his first economics class as a scholarship student at Princeton. “I rank this Bogle invention along with the invention of the wheel,” the late Samuelson wrote, “the alphabet, Gutenberg printing, and wine and cheese: a mutual fund that never made Bogle rich but elevated the long-term returns of the mutual-fund owners. Something new under the sun.”

Jack Bogle signed a lot of copies of his latest book that day, then went home, declining to join the Bogleheads when they boarded buses and rode to the Vanguard corporate campus for a reception and some question-and-answer sessions with executives.

The next morning, Bogle got out of bed again — his second rule of life is “Repeat rule number one the next day” — donned khaki pants, slipped a crewneck sweater over his button-down shirt, and went to the Bogleheads’ hotel conference room for a Q&A with his acolytes. There were plenty of questions about the technicalities of investing, which even Bogle says can be as exciting as watching grass grow.

For all his feistiness, Bogle is showing his age, and even he is starting to joke that he can safely make predictions now because he won’t be around to see if he’s wrong. At one point, a Boglehead asked if he ever sits back and appreciates the huge impact he’s made on the industry he changed and all the people he has helped. The voluble Saint Jack got a little hesitant and seemed to choke up; his eyes looked moist as he talked of believing he had a ministry.

“I don’t want to make this too personal,” he said. “But I just want to be the same kind of kid I grew up as. I don’t want to change. I had high values. I tried to set a good example. I took responsibility. I worked hard. Tried to do things the right way to help the community and the investor … and that’s good enough for me.

“When I look at some of those monkeys that are on the Forbes list, I have no envy. They all have more money than I do. I don’t give a damn. Not a damn.” When the head Bogleheads wrote their book, they dedicated it to Bogle, naturally, with the phrase, “While some mutual fund founders chose to make billions, he chose to make a difference.”

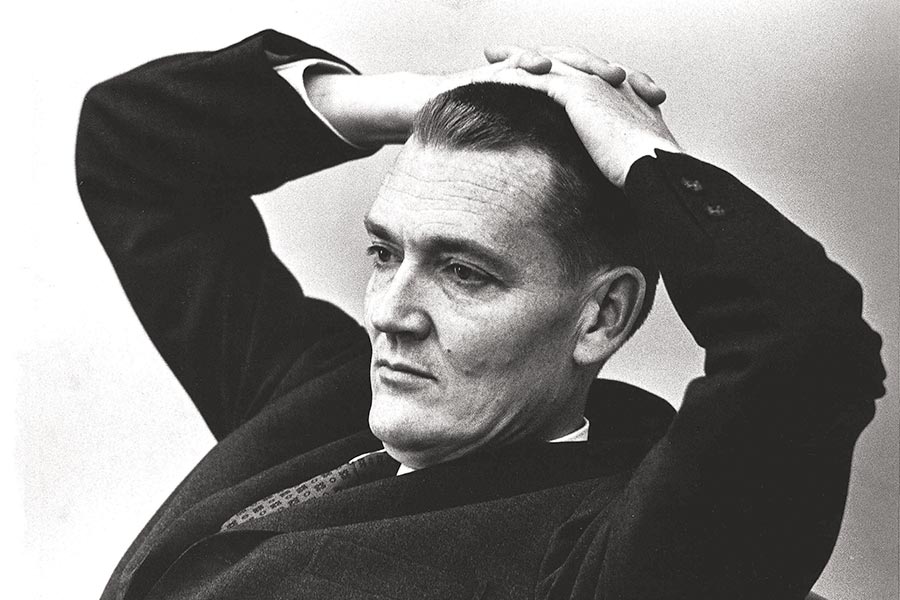

A young Jack Bogle in his Wellington days. Photograph courtesy of Jack Bogle

The original $10 million that Jack Bogle scraped together to create the indexed mutual fund that launched the company might now seem like a rounding error in the $5 trillion colossus. And while Bogle may have resisted change both personally and professionally, his company is certainly a different place. As Tim Buckley takes the helm of what one longtime executive described to me as “the Good Ship Vanguard” — only the fourth CEO in more than 40 years — it would appear he’s been handed the wheel of a financial juggernaut. But there are also signs the Good Ship may be springing a few leaks.

Buckley is a youthful, trim and athletic 48-year-old who looks like someone a casting director would pick to be CEO. Kerry Pechter of Retirement Income Journal remembers him as a young executive giving a presentation to Vanguard employees: “He was preternaturally polished. I could not believe how self-possessed he was — the perfect human being.”

“What to say about Tim?” Bogle tells me. “He gets things done. He’s very good on technology and all that. He, like all of us, still has a lot to learn. You never know quite how a CEO is going to behave. People tell me he does not do a lot of communicating. Communicating is something a chief executive has to do.”

(Buckley wouldn’t communicate with me. Vanguard’s top PR people declined repeated requests for an interview with him for this story. When I tried to approach him at the investment conference in New York where he’d just sat for nearly an hour of questions from a friendly business associate, Vanguard’s head of PR shot at me as she ran interference: “He’s not giving any interviews.”)

“The interesting thing here is, Vanguard really grew on free publicity, and Jack Bogle was a master at managing the public perception of the company,” says the Inquirer’s veteran business columnist, Joe DiStefano, who has covered Vanguard for years. Buckley hasn’t spoken to him yet, either. A Vanguard PR executive tells me, “The Inquirer doesn’t think we can do anything right.”

The explosive growth of Vanguard’s resources is changing its image from frugal, scrappy underdog to fat cat. Competitors are taking direct aim, and scrutiny of the company has become more intense and more frequently critical. There have been reports that its vaunted cultish culture may be in decline. Recently, the Inquirer has reported on a raft of age and sex discrimination claims by former employees. Many who follow the company, even among the devoted Bogleheads, have noted that customer service has been hard-pressed to keep up with the increasing number of investors. While a recent hiring binge was meant to address that problem, the employee website Glassdoor is full of negative comments (delivered, granted, anonymously) from employees, and per the site, Vanguard has lower employee satisfaction levels than its peers. Though it was once a fixture on Fortune magazine’s annual list of best places to work, it hasn’t made the cut in a decade.

Outside observers have started asking harder questions about management practices. One of the most active and astute, Dan Wiener of the Independent Adviser for Vanguard Investors website, has noticed that service, especially through the company’s website, is faltering. “Come on Vanguard,” Wiener chided in an e-mail to subscribers of his newsletter, “you really CAN do better.”

The Inquirer’s DiStefano points out what is perhaps the most salient problem facing the company as it lumbers into the future, no longer a big friendly giant but a certified colossus: “It’s a tough business, and they’ve done very well by competing on price. But now that there are other companies offering competitive prices, they’ll have to compete on service. And I hear a lot of bad things about their customer service.”

DiStefano and others have been probing more forcefully the rather opaque way the company distributes and retains the “profits” it likes to pretend it doesn’t make. He has also covered the complicated “whistle-blower” lawsuit by a former Vanguard lawyer who charges that the company has been using its unusual ownership structure to avoid paying taxes for decades. (According to reports, Vanguard settled a Texas inquiry that saw the lawyer who brought the original suit awarded a $117K whistle-blower fee.) The allegations are what an industry-observer website, RIABiz, called “the closest thing Vanguard has to an existential threat.” One tax expert estimated that in a worst-case scenario for the company, Vanguard could owe nearly $35 billion in back taxes and penalties. Even with $5 trillion in assets under management, that kind of hit wouldn’t be a rounding error.

“I think they could absorb it,” says DiStefano. “And they would have to get hit awfully hard to force a substantial increase in their fees. But yeah, $35 billion would really hurt them.”

“Vanguard has been very hesitant about discussing that lawsuit,” Bogle tells me. “As they should be. They certainly haven’t talked to me about it. But I can’t imagine that lawsuit will be successful.”

While Vanguard has publicly acknowledged its customer service problems, the company’s standard mode of dealing with challenging and sometimes harsh press coverage is to dismiss any allegations or refuse comment.

An exception came just after the Bogleheads’ annual visit with Saint Jack. Ever the gadfly, Bogle gave an interview to a top analyst at Morningstar and told her that Vanguard may simply be reaching the point of being too big. (Vanguard must sometimes wish its founder would remain as mute as the statue outside his office.) The company responded by pointing out that the founder hasn’t been CEO or involved in its operations for more than 20 years.

“I think that’s a perfectly fair response,” Bogle tells me. “It’s easy for me to talk. I don’t have to take any responsibility for the consequences.” Then the man who told his acolytes he was simply a good kid who didn’t ever want to change describes himself as “an emperor’s-clothes kind of kid.”

“I can’t shirk the truth as I see it. I try and make sure I’m fair to the company. I have the company’s interest in mind with everything I do. Sometimes I’m more successful than others. Anyone would tell you that I have a reputation for candor. Letting the chips fall where they may is a big part of what built this place. I don’t think anybody expects me to stop.”

When he gets started on weighing the value of what he does with himself after getting out of bed each morning, Saint Jack, the 18th-century man heading toward his 10th decade, finds it necessary to go back a few millennia for his aphorism. “I’m called on to quote Sophocles,” he tells me. “‘One must wait until the evening to enjoy the splendor of the day.’ My evening is not here yet.”

Published as “The Cult of Saint Jack” in the January 2018 issue of Philadelphia magazine.