Kenjon Barner: With Family In Mind

Photo by: Jeff Fusco.

Maisha Barner ran onto Rogers Field screaming hysterically in October of 2010. Her baby brother, Kenjon Barner, lay motionless on the ground in his Oregon uniform after being knocked unconscious on a kick return.

“Kenjon, get up!”

Barner was running an “opposite return,” calling for him to take a few steps up the field on the left side before cutting back to the right. As he was cutting back, though, a teammate blocked a Washington State player directly into Barner’s blind spot, and initiated a helmet-to-helmet collision.

“That was really scary for all of us on the team,” said Jeff Maehl, who was on Oregon’s sideline. “You knew it was bad right when it happened.”

Barner doesn’t remember the play, being transported off the field or the two days he spent in a Washington hospital. Even after he was flown to Oregon for further observation, he didn’t remember everyone who visited him.

Barner was kept in a dark room, and almost always had friends by his side after his family returned home. Many of his teammates came to see him—particularly LaMichael James—and two of his close friends who didn’t play football—Trevor Clemens and Andrew Hughes—took rotating shifts with James.

After about a week in the two hospitals, Kenjon left with a recommendation from the doctors: quit football.

“He came to a crossroads,” Maisha said. “Football is obviously a dangerous sport and he had to think about if this was really something he wanted to do. He already had a love for the sport, but I think it went to a whole other level after that.”

The redshirt sophomore was cleared to return after a few weeks, but was never very close to quitting. He did, however, take one thing from the experience.

“Once I came back and recovered, I knew there was no way I was returning another ball,” Kenjon said. “I was done with that.”

KENJON’S KINSHIP

Beverly Blanchard started to worry. She rarely allowed her son to stay out late, but on this night, her 15-year-old wanted to attend a high school basketball game with his cousin and friends.

As the night dragged on, she kept glancing at the clock. She made it clear that he had to be home by 10 p.m., so when he wasn’t, she went looking for him. She quickly found him around the corner, and suddenly saw two young men walking toward her son from the other end of the street.

“What set are you from?” one of them asked.

“I’m not in a gang,” Kenjon responded.

The strangers weren’t satisfied, however, and one of them pulled out a gun. Blanchard started sprinting toward her son, but the gunman fired a shot. She ran even faster toward her son, but the gunman fired another shot while Kenjon was writhing in pain on the ground.

The gunman, later identified as Carmen Ward, then shot one of Kenjon’s friends—Kenneth Shy—in the leg before fleeing.

Soon after, he was taken to the hospital and underwent surgery. The next morning, however, David Kenjon Adkins was declared dead on February 21, 1988.

“I almost lost my mind,” Blanchard said.

Blanchard’s brother—Gary Barner—was also deeply disturbed by Adkins’ murder. The two were so close that when they were together, Barner often told people his nephew was his son.

“He touched everyone in the family,” Gary said. “He had such an impact on all of our lives and his death affected us so much. I just told my mother that I would find this guy.”

Barner, who worked as a gang counselor for several years, had every intention of following through. The murder happened in one of his areas of concentration—Lynwood, California—so he went into the streets and spent countless hours asking questions.

One day, he received a tip about where Ward was staying. After confirming it—and coming face-to-face with his nephew’s killer—he reported it to the police.

Nearly three years after Adkins’ death, Ward, 21, became the youngest person sentenced to California’s Death Row in January of 1991. Barner, meanwhile, welcomed a new baby boy to his family on April 28, 1989.

He named him Kenjon Fa’terrell Barner.

‘DOOGIE’

When Barner was born just a year after Adkins’ death, Blanchard couldn’t believe her eyes.

“After he was born, he looked like my Kenjon’s twin,” she said. “If you saw a picture of my Kenjon and him together, it’s eerie how much they look alike.”

As she quickly found out, that’s not the only striking similarity. According to family members, they share key personality traits as well: good manners, extreme lovingness and a desire to go to great lengths to help others.

The only difference? “My nephew has a bigger sized foot,” Blanchard said.

That’s why when Barner was born, Blanchard couldn’t bring herself to call him by his name. She loved watching Doogie Howser, M.D., so she gave him a nickname that still sticks with him today: Doogie.

Despite this, she was still honored when her brother and his wife called to ask if they could name their son Kenjon. Twenty-six years later, she’s able to speak his name when talking to a reporter.

“It means the world to me because Kenjon is such a good kid,” Blanchard said, teary-eyed. “He’s just an exceptional kid and that’s how my baby was. Very exceptional.”

It’s a reciprocal relationship, and Barner has felt the pressure—no, responsibility—to honor not just his cousin, but his aunt and godmother. He explains that, in addition to his family’s and friends’ support, his late cousin’s memory has been his guide to navigating the treacherous waters life put in front of him.

“I never had the opportunity to meet my cousin so for me, as I grew up and understood what he meant to her, it was crucial for me to carry myself in a light that would not only make her proud, but make him proud as well,” Barner said.

“I wanted to do everything I could to make her smile. I wanted to give her every ounce of happiness I could because I carry his name. Still to this day, I want to give her every bit of happiness she could have possibly experienced through Kenjon that she missed out on because his life was cut short.”

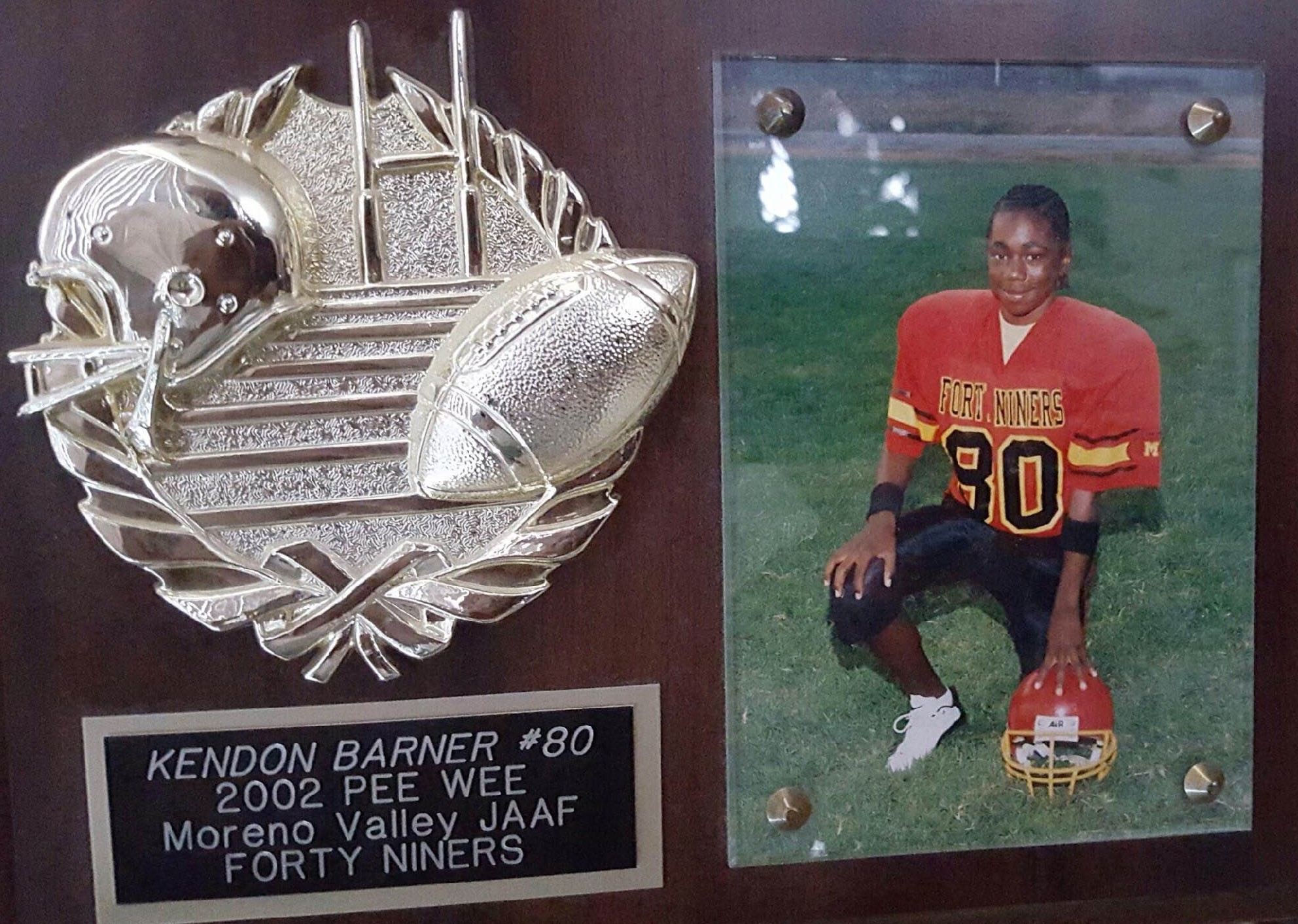

Photo courtesy of the Barner family.

‘I’M GOING TO THE NFL’

After their nephew’s death—and experiencing other tragedies—Gary and Wilhelmenia Barner decided to move. They left Los Angeles for Cypress, before eventually settling on Moreno Valley.

“I thought if I moved them away, I’ll probably save their lives,” Gary said. “They could focus on their education and not all of that other stuff.”

Although the family moved away from a lot of violence and negative influences, they also moved away from much of their extended family. As a result, they grew extremely close to each other.

The children spent a lot of time with one another, including when Kenjon’s older brothers snuck him to the park because their mother didn’t want him playing football. One of her neighbors told her year after year she should let her son play football, but she always refused.

“I just thought he was too small to play,” Wilhelmenia said. “He was an itty bitty kid and I didn’t want to see him get hurt.”

Although she relented after a few years, she did so on one stipulation: Kenjon had to quit if he ever got hurt. He agreed.

Soon after, he donned the red, gold and black for the Moreno Valley Forty Niners. He played wide receiver, partially because he hated running back (“I couldn’t find the hole,” he said. “It was just a tragedy.”) The season went smoothly, until one game when he ran a slant route and was hit hard by defender. His teammates helped him to the sideline, before he saw his mother.

“Well, you know what our deal was,” she said. “That’s it.”

Because he couldn’t play anymore, Kenjon focused on basketball. His talent on the court quickly showed, and his father had high hopes for him. Gary thought Kenjon found the key to becoming the first person in the family to attend college.

But on the first day of his AAU season one year, Kenjon had a change of heart. When his dad came into his room to wake him up, Kenjon said he didn’t want to play anymore.

“Understand something, son,” Gary told him. “I don’t have the finances to pay your way through college. You could get a scholarship for basketball to pay your way through school! What are you going to do with your life?”

“I’m going to the NFL,” Kenjon responded.

“I’m going to go get your mother,” Gary concluded.

SACRIFICE

Kenjon was worried about what his mother would say. After banning him from football a few years earlier, he decided to try-out for his high school football team as a freshman.

When he made it, he realized he had to tell his mother.

“I wasn’t happy,” she says now.

But she agreed to let him play, and quickly saw his talent for the sport. As Kenjon played more and more, his family saw where the game could take him. As a family, they decided to do everything they could—sacrifice precious time, money and opportunities—to support his dream.

“We all saw our parents struggle,” Maisha said. “We weren’t rich in money, but we were rich in our faith and our family. For Doogie to witness that, it’s a piece of what drove him.”

In an effort to support him and help him earn a football scholarship, the entire family pooled money to hire a trainer and pay for other expenses. Their sacrifices paid off, and by his junior year, Kenjon began receiving scholarship offers.

With this success, however, came unexpected obstacles. Because no one in their immediate family attended college, they didn’t know how to ensure he was eligible. Then they met Bobby Pleasant.

“Bobby Pleasant was the most instrumental piece—outside of my family—in helping me get to college,” Kenjon said. “We had no idea how to go about things. Bobby helped us the entire way.”

Pleasant helped Kenjon and his family with all of the paperwork and explained how the NCAA Clearinghouse worked. Pleasant, a former college football player himself, offered his time and help to many of the local kids trying to make it out of the area.

Now that he knew he was eligible and had several offers, Kenjon had to figure out where he would go. He knew he wanted to leave the area, because he wanted to completely separate himself from the fate of many of his friends—death or jail.

He settled on Arizona State, because it was far enough away from home and one of his brothers lived in Phoenix. They wanted him to commit soon, however, and another local running back ended up accepting a scholarship.

Then he turned his attention to Oregon, and finalized his acceptance and entry into college.

“When Kenjon received a scholarship from the University of Oregon, that was the second happiest day of my life,” Gary said, fighting back tears. “Kenjon is our baby; I knew then that he would live a secure life. I still thank God to this day.”

TREVOR AND ANDREW

Kenjon had had enough. He packed up his clothes, talked to his family and said he was coming home. He couldn’t bear being away from them anymore.

“When football was over but he was still in school, I think that was tough for him because he was used to us coming up there every weekend,” said Martel Barner, one of Kenjon’s older brothers.

Kenjon was struggling, so much so that his sister worried about all the time he was spending alone. Not far into his freshman year, Kenjon was put on academic probation because of his bad grades.

“My freshman year was an absolute disaster,” he said. “Learning to adjust away from my family was extremely hard.”

He had never been away from home for more than a few days before college, so he wasn’t used to being responsible for waking up for class and staying on top of his homework without being told to.

Not far into his freshman year, Kenjon met Trevor Clemens and Andrew Hughes. The trio quickly developed a bond by playing basketball almost every day, watching Step Brothers and playing Call of Duty.

They also had one more commonality: they were all on academic probation.

“We made a little promise to each other,” Hughes said. “You miss a class here, you miss a class there? That happens. But once you start making a pattern of it, that’s when we’ll sit each other down.”

The trio stuck to that pact, and one day when finals were coming up and Kenjon wasn’t going to class, they had a word with him. He was sleeping on their couch—something that often happened—but they woke him up to make him attend a class he was going to skip.

“A lot could’ve gone bad without those guys,” Kenjon said. “Trevor and Andrew are a major reason I was able to make it through college. Without those guys, I probably would’ve gotten in trouble.”

Trevor and Andrew didn’t mind, because it went both ways. It didn’t take long for the three of them to get back on track and off academic probation.

The three became so close, Kenjon ate family dinners at his friends’ homes (both were locals). He even called their moms on Mother’s Day and helped Hughes’ little brother when he was having problems in high school.

“I technically have six brothers, but I really have more than that,” Maisha said. “Trevor and Andrew have been there through the good and the bad. They’ve been a constant push and constant support. They held him accountable and he needed that.”

Photo courtesy of USA Today Sports.

‘HEAVEN SENT’

Kenjon called his dad for help. He wasn’t sure what to do.

Around the same time Chip Kelly earned a promotion from offensive coordinator to head coach at Oregon in 2009, he came to Kenjon with a question: How do you feel about playing running back instead of corner?

Although Kenjon was a standout running back in high school, Oregon recruited him as a defensive back. After his freshman year, however, Remene Alston, Jr., LeGarrette Blount and James all suffered injuries.

Kelly needed someone—anyone—in the backfield so they could complete spring practices. Kenjon agreed.

“It was just a matter of trying to get a guy to finish out spring practice,” Kelly said, “and obviously [it] caught our eye that he’s pretty talented on that side of the ball. We had some depth in the secondary at the time, so we transitioned him over.”

It didn’t take long for Kenjon to make an impact. As a redshirt freshman, he scored three rushing touchdowns, returned a kick for a touchdown and averaged six yards a carry. As a redshirt sophomore, he totaled nine touchdowns—six rushing, two receiving and one punt return—despite missing several games because of his concussion.

As a redshirt junior, he combined for 14 touchdowns—11 rushing and three receiving—and more than 1,000 yards out of the backfield. When he announced his return for his final season, some media labeled him as a Heisman Trophy candidate. Although he wasn’t named a finalist for the award, he did rush for 21 touchdowns (tying the school record) and 1,767 yards (second-most in Oregon history) on his way to becoming an All-American.

Despite his on-field accomplishments, however, his college graduation and degree in criminology touched his family on a much deeper level.

“For me, Coach Kelly was heaven sent,” Gary said, speaking through tears. “I’m forever, for the rest of my life, thankful, to Oregon and Coach Kelly for being men of their words. They took care of him. For Kenjon to go to college, overcome homesickness and get his degree, it gave me a joy that I still have today.”

KINGSTON

Martel noticed something different about his youngest brother. He isn’t sure when it happened or why it happened, but he’s just happy that it did.

“I’ve seen something different in him that I haven’t seen since his senior year in college,” Martel said. “He has a spark. Whatever made him have that look in his eyes, I’m glad whatever it was.”

After a reporter relays his brother’s thoughts, Kenjon smiles. He knows exactly what he’s talking about.

“My mentality changed because of my son,” Kenjon said. “I don’t want my son to grow up and ever have to wonder why his dad couldn’t support him. Because I can’t be in my son’s life every day, I have to make sure I do everything I can when I’m training and playing football so he understands his dad is working hard for him to live the life he has.”

Kenjon’s son, Kingston, was born in May of 2013, just weeks after the Carolina Panthers selected Kenjon in the sixth round of the draft. The day after Kingston’s birth, however, Kenjon had to leave for rookie minicamp and didn’t re-join him and his mother in Oregon until after OTAs.

After one week, Kenjon reported back to the Panthers for training camp. He appeared in eight games for Carolina and couldn’t spend much time with his son again until the Panthers’ season ended. But as Kenjon has spent more time with his son, the flame Kingston ignited grows stronger and stronger.

“He wants his son to be proud of the man he is,” Maisha said. “He’s seen his friends back home that are either not here anymore or are locked away.”

He hoped to do that last year after the Eagles traded for him, but Kenjon injured his left ankle in the preseason finale against the Jets. He then received the waived/injured designation, but was signed to the practice squad a few months later in November.

Since starting the 2015 offseason with a clean bill of health, Kenjon has made a strong case to make the 53-man roster after returning a punt for a touchdown in each of the first two preseason games. A year after losing a potential roster spot against the Jets, he will try to do the opposite tonight in New York.

“I’m excited about how I’ve done so far, but I know there’s more work to do,” he said. “I can’t get complacent and I can’t get satisfied with where I am, and I’m not.”