What Any Family Wants

What if the kids in my clinic were your kids?

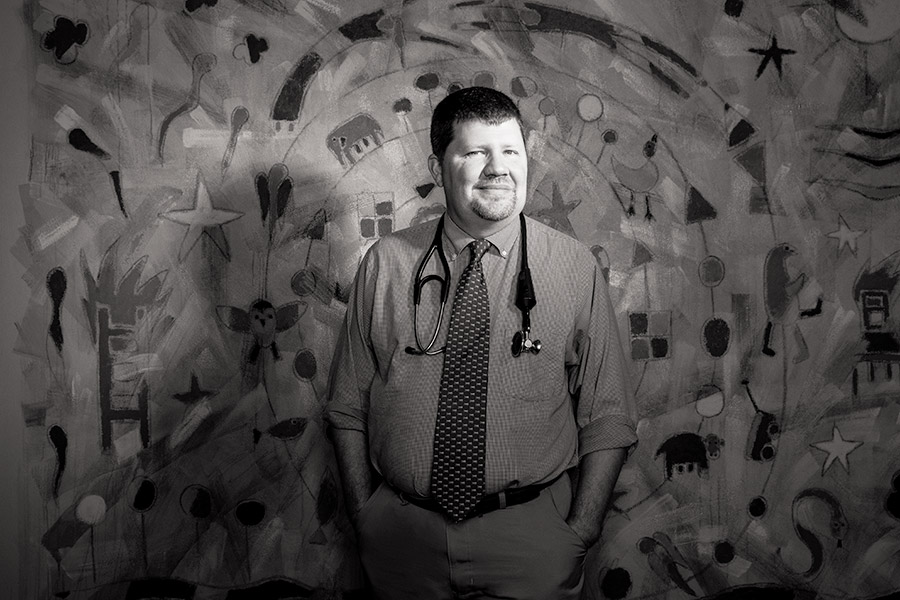

Christopher Raab. Photograph by Colin Lenton

As director of the Nemours pediatric refugee clinics in Philadelphia and Wilmington, I’ve been privileged to welcome more than 750 refugee children and their families to our country and our region. They come from all over the world — from countries like Bhutan, Iraq, Syria, Congo, Ukraine. They’ve fled war and persecution but arrive in our clinic with smiles and happiness — at least, until they find out about the immunization shots they need.

The Wednesday-morning clinic in Philadelphia is my favorite time of the week. We do follow-up visits with some of the families, then see new arrivals. I often get a hearty handshake from a father, or a worried mother drags a child over to ask about a rash. I get to chat with one mother — an English teacher back in Syria — who always asks how far I’ve gotten in the kindergarten-level Arabic alphabet book she gave me (not far). I catch up with a Nepalese father whose oldest son was one of our patients but now is in college, studying engineering. One of my Syrian patients always asks about how to get into college, so she can become a pediatrician and work with me in the clinic. Clinic is a bit chaotic, with lots of languages in the air and our pediatric residents (who do the hard work) scurrying from one room to the next, but it’s my happy place.

Unfortunately, not all of the conversations are easy or fun. We treat children and teens who are seriously ill, who have been shot or raped, who are scared and anxious. Being a teenager is hard enough; being a teenager in a new country is especially hard. But their resilience and grit are remarkable. I guess to be one of the lucky ones who come to America, you have to be tough.

All of us, unless we’re of Native American heritage, come from an immigrant background. Most of my ancestors came to this country from England before the American Revolution, but they still arrived long after the first refugees came to North America, fleeing religious persecution. The children who come to our clinic each week aren’t much different from the immigrants who sailed for America in search of better lives, though I’d argue they may be even more deserving of a chance at the “American dream.” Many have lived in squalid refugee camps or city wards for the entirety of their lives, or have been witnesses to war. They fled their homes when bombs began to fall in Syria; they were forced out of their villages by Burmese troops. They moved from one country to the next, unable to control their destiny, taken in by the U.N. until they could be sent home again or resettled elsewhere.

Despite these families’ different backgrounds and cultures, the one commonality I see among them is their desire to provide a better life and more opportunity for their children than they had. Is that any different from families anywhere else? It’s certainly what I want for my three children — that they get the chance to do what they love. My parents wanted that, too, and made it a reality for me: I am a pediatrician caring for refugee children.

Christopher Raab is director of the Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children Refugee Clinics in Wilmington and Philadelphia and medical director of the Nemours International Medicine Program.

» See Also: Top Doctors 2018: The Stories They Tell

Published as “The Stories They Tell … ” in the May 2018 issue of Philadelphia magazine.