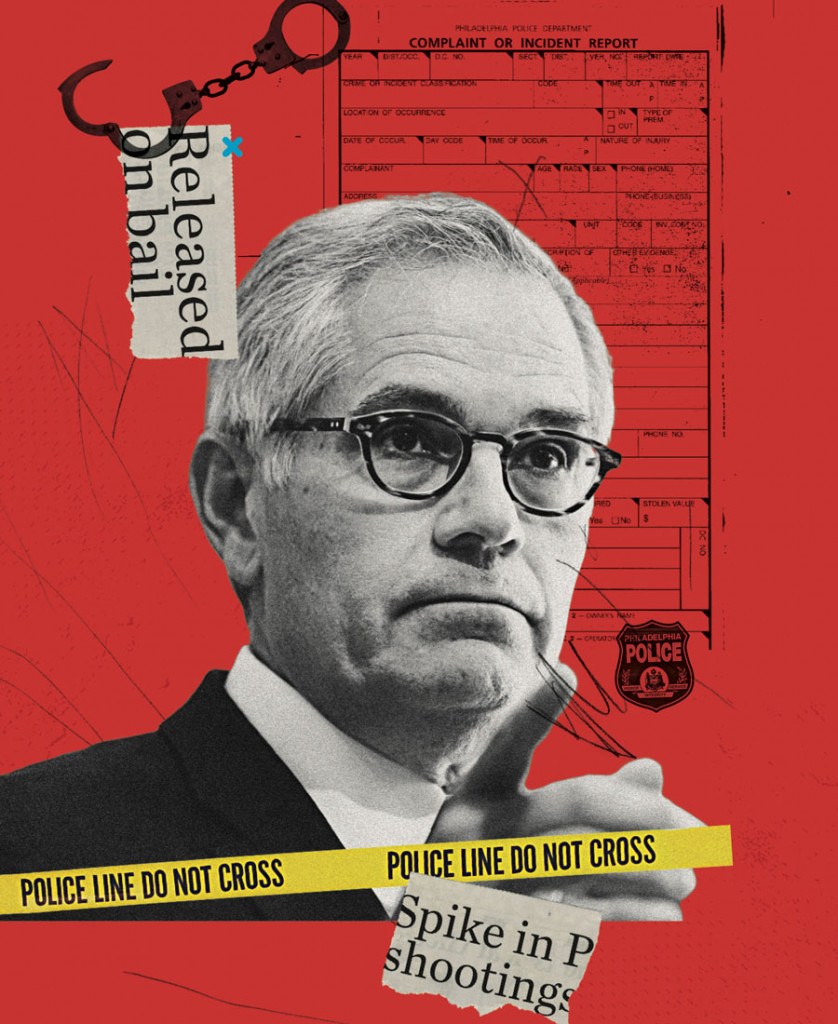

Larry Krasner vs. Everybody: Inside the Philly DA’s Crusade to Revolutionize Criminal Justice

What, you thought blowing up the system was going to come without a fight?

Inside Larry Krasner’s battles for criminal justice reform. Photograph of Krasner by Matt Rourke/Associated Press; police tape and handcuffs: Getty Images.

Shortly after U.S. Attorney Bill McSwain took office in April 2018, he met with Larry Krasner.

McSwain, his close-cropped hair and ramrod posture reflecting his status as a former Marine, came to Krasner’s office, a long, airy room decorated with minimalist precision. The two men shook hands and moved to a formal sitting area, where presumably they’d get to know each other.

Krasner, who’d held the DA’s office for less than six months by that time, saw the meeting as a step toward a working relationship. But, he says, his guest had other ideas. McSwain, in Krasner’s account of the meeting, immediately launched into “talking points” that echoed those of the Trump administration.

McSwain is a Trump appointee, and Justice Department officials in the Trump administration express great disdain for the reform movement Krasner represents. “He was surly, accusatory and nasty in ways that are not all rational,” says Krasner. “If your stated purpose was to come and meet and talk about how we can work together, it was evident that he had a totally different agenda.”

Krasner fired back, delivering a final, frank prediction as the meeting closed. “You are gonna lose and Trump’s going to lose,” he told McSwain, “because history is not on your side.”

That, anyway, is Krasner’s version.

McSwain, for his part, says he entered into the meeting expecting a collegial search for common ground. Krasner, however, had other ideas. McSwain says the DA “got up on his soapbox” to lecture him about justice reform and how traditional prosecutors got it all wrong. “He said, ‘I think what went on here the last 20 years is terrible, and I’m here to burn it all down,’” recalls McSwain. “And the reason he wants to do that is he thinks the entire system … meaning the police, the whole criminal justice system, is racist and corrupt.”

As a career defense attorney who’d never prosecuted a case in his life, Larry Krasner did promise a radical reworking of the DA’s office — an end to what he called the “crisis of mass incarceration.” He won, improbably, in part because of major campaign spending by liberal billionaire George Soros. Now, nearly two years into his first term, he’s shown he can deliver on what he promised, diverting nonviolent offenders from prison and eliminating cash bail for some charges.* But the victories have come with controversy — including, most spectacularly, some dramatic skirmishes with his fellow top law enforcement officers.

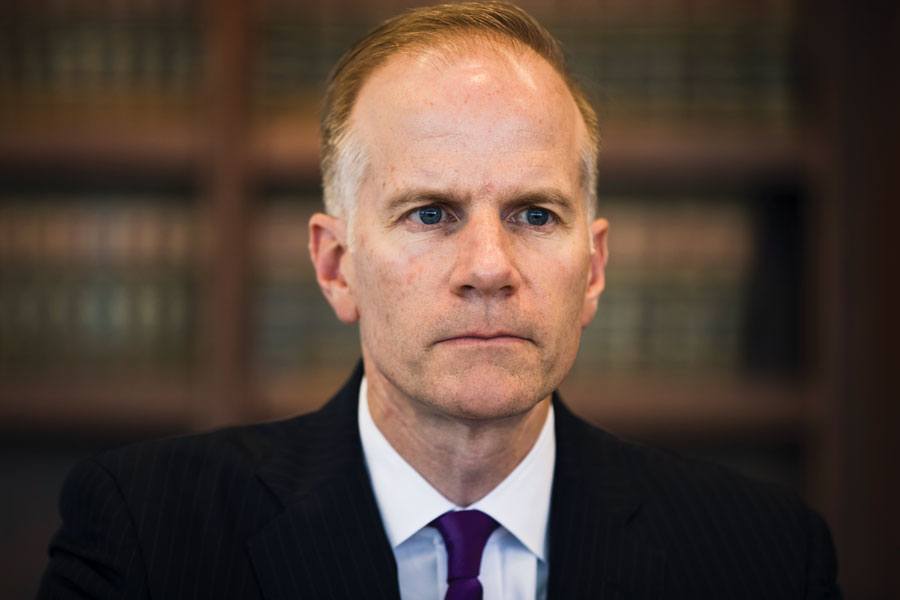

U.S. Attorney Bill McSwain, who’s criticized Krasner repeatedly. Photograph by Matt Rourke/Associated Press

In the year and a half since their one face-to-face meeting, for instance, McSwain has publicly and repeatedly trashed Philly’s DA, proclaiming that he’s made the city unsafe. “He has an interest in sort of cramming down his radical pro-defendant ideology on everyone else,” McSwain told Fox News’s Tucker Carlson this past June. Two months later, in the wake of last summer’s dramatic police hostage situation in North Philly — in which six cops were shot in a standoff that lasted for almost eight hours — McSwain upped the ante even more, releasing a startling written statement claiming that the gunman displayed a disrespect for law enforcement “promoted and championed” by Krasner. “It started with chants at the DA’s victory party — chants of ‘F— the police’ and ‘No good cops in a racist system,’” he wrote. “We’ve now endured over a year and a half of the worst kinds of slander against law enforcement — the DA routinely calls police and prosecutors corrupt and racist. … ”

The heat was certainly unusual after a night on which tragedy had largely been averted. But it shouldn’t have been surprising. When it comes to McSwain, Krasner gives as good as he gets, once calling the U.S. Attorney, straight up, “a liar.”

It’s not only conservatives that Krasner has tangled with, however. Earlier this year he opened a new war front, going after Democratic state Attorney General Josh Shapiro, whom he cast as “fork-tongued” in a Los Angeles Times article.

On one level, the battles are a by-product of Krasner’s brash personality. “I think he ends up in these fights, particularly with Shapiro, because he has a big ego,” says veteran political strategist Neil Oxman. “For a guy who won office with the help of an atom bomb of funding from one guy, he seems awfully full of himself.”

But Krasner’s wars also symbolize something much bigger: the tectonic political and cultural upheaval that’s now happening in Philly and across the country as the far left pushes for revolutionary change, the far right doubles down on making America “great again,” and the once-broad-and-steady center slowly evaporates.

Like him or not, Larry Krasner is a figure of history. Donald J. Trump’s election to the White House triggered a new liberal resistance movement, and Krasner’s résumé fit the moment. As a defense and civil rights attorney, he sued the police at least 75 times in his career. He defended left-leaning protesters like Occupy Philadelphia. And he wasn’t afraid to call out racist behavior as, well, racist.

For decades, America’s DA candidates competed to be tough, tougher, and finally batshit crazy on crime. The phrase “We speak for the victim” was deployed by DAs coast to coast as a self-righteous promotional banner, and our nation’s prison population boomed — from 300,000 people in 1970 to more than two million. Blacks and Latinos represented 56 percent of the prison population but just 32 percent of America’s citizenry. Minorities faced stiffer prison sentences than whites with similar records and crimes.

And none of it came cheap. The annual cost of locking people up was $60 billion nationally, and $300 million of this city’s budget. But was this spending necessary? A 2016 Brennan Center study found that 14 percent of prison inmates had been incarcerated so long that they’d aged out of any meaningful risk to commit crime again. A full 25 percent of the country’s prison inmates were low-level non-violent offenders. The Philadelphia jail system was overcrowded, and 30 percent of the inmates there were awaiting trial — legally innocent but unable to make bail.

Touting his election as a “movement,” Krasner won by dint of all this history. Though he’s one of more than a dozen reform DAs Soros helped to elect, by summer 2018 Krasner had emerged as a standard-bearer. His elfin looks, outspoken views and sense of humor — he delighted in calling himself “unelectable” — proved catnip to national media, fueling appearances on HBO and Comedy Central and in an MSNBC special. In the span of about a week, longform Krasner profiles appeared in the New Yorker, the New York Times Sunday Magazine and Newsweek (the last of those written by me).

A segment on HBO’s now-defunct Vice News program foretold the brawling we see today. “You have someone,” Krasner’s interviewer began, “in the person of Jeff Sessions, at the helm of the Justice Department, who has views that are pretty much diametrically opposed — ”

“Did you say ‘person’?” Krasner interrupted.

The DA appeared to delight in the shocked silence that followed, breaking into an impish, self-satisfied smile.

Pressed, Krasner noted that Sessions had earlier been rejected from the federal bench over racism. Perhaps the dig was earned, but in that moment, Krasner also revealed something in himself: a capacity to dehumanize his opponents and amp up conflicts, rather than toning them down.

“The thing about Larry is that none of this is an act,” says longtime city defense attorney Jack McMahon. “He’s fought these fights, dedicated his career to them, for decades. And so he isn’t going to back down or modulate, because he didn’t do this to seek higher offices. He is who he is.”

In person, Krasner is fighting-trim at 58, with salt-and-pepper hair, hipster eyeglasses, and the air of a charismatic college professor. And if he seeks reelection in two years, he’ll have a record to run on — and against.

During his first week in office, he dismissed 31 staffers. Further departures followed. Today, he boasts of his new hires — 65 in a recent haul, most of them women and a high percentage minority. “That’s a big deal,” he says one day in his office. “They are coming here because they are ideologically attached to the mission.”

The mission he conceives is to return prosecutors to their primary duty, as defined by courts and the American Bar Association, to “seek justice” — a balancing act of societal interests, rather than the single-minded focus on speaking for victims the profession had become.

In practice, Krasner has decriminalized weed possession and some prostitution offenses and made bail reforms. He’s also overhauled the entire office’s charging procedures, even for gun and violent offenses. And last April, he boasted during a City Council budget hearing about the money he’s saved: $82 million in city and state savings per quarter, with an additional $13.8 million shaved off probation and parole costs. In response, the Inquirer noted, City Councilman Allan Domb lifted his arms in apparent triumph.

Not that there haven’t been times when Krasner and his staff have looked beleaguered. When I interviewed him for Newsweek in the summer of 2018, Krasner expressed some doubt about seeking a second term. “I’m not a politician,” he said. “I have no intention of running for any other office, and I’m not even sure I’ll run again for this one.”

Today, though, his mood seems different. Looking back, Krasner calls what he’s accomplished so far “chapter one. In which we leave people shocked and amazed by actually doing the things we said we’d do.”

Chapter two, he says, is that “we’ve woken up the giants.”

The giants?

Yeah, the giants, he responds, eventually winding his way through a list that includes the National Rifle Association, the Fraternal Order of Police, politicians and the prison industrial complex, the political right, moderate Democrats and more. The giants, he says, “have come to realize we represent an existential threat not only to the judiciary, but to the established way of doing business in the Philadelphia Democratic Party.”

After that first ill-fated meeting, Bill McSwain made an attempt to normalize relations with Larry Krasner, inviting him to a monthly confab he started of regional law enforcement officials.

Larry Krasner didn’t even attend, let alone bring doughnuts, sending an emissary to the first meeting and, as McSwain tells it, no one in the months after.

I meet with McSwain late in September in a large, unremarkable conference room adjoining his office at 6th and Chestnut. I want to hear his concerns about Krasner — an opening that seems to paralyze him for a moment as he considers where to begin. “His policies have been a disaster for Philadelphia,” he says, adding that Krasner has “abdicated” his responsibility as a prosecutor and disrespected democracy by failing to enforce the law as it’s been passed down to him. The DA, he says, will sacrifice public safety because he just wants to implement his “radical ideological agenda.”

“His policies have been a disaster for Philadelphia,” McSwain says of Krasner, adding that the DA has “abdicated” his responsibility as a prosecutor and disrespected democracy.

There are specifics. McSwain notes that crime, from retail theft to gun violence, has increased since Krasner came into office. And at first glance, Krasner’s policy on retail theft does look soft. Under his leadership, thefts involving merchandise worth less than $500 are treated as summary offenses, punishable by fines instead of jail time. McSwain, calling this an invitation for thieves to steal $499 leather jackets, says he’s “done a lot of work on this,” going out to meet with shop owners. He cannot, however, introduce any of these store owners to me, he says, because they’re afraid of retribution by Krasner or that “criminals will burn down” their shops.

What’s more, he notes, this crisis won’t be reflected in any statistics: Cops don’t bother to investigate non-criminal offenses. Store owners don’t bother to call.

If McSwain is right, though, store owners themselves appear unaware of it. “We regularly convene a working group of commercial-corridor managers who directly interact with small, primarily retail businesses on neighborhood commercial corridors,” Rick Sauer, executive director of the Philadelphia Association of Community Development Corporations, said in an email, “and [shoplifting] is not an issue they have raised.”

Maureen Faulkner in October, protesting Krasner’s handling of the Mumia Abu-Jamal case. Photograph by Tim Tai/The Philadelphia Inquirer/Associated Press

The gun violence, however, verifiably exists. Homicides in the city are up six percent and shootings are up 10 percent this year. The problem is that crime stats often rise or fall, for reasons that can be difficult to explain. For example, gun violence rose here from 2004 to 2006, during the tenure of Lynne Abraham, a diminutive, grandmotherly-looking DA who sought the death penalty so routinely that the New York Times dubbed her “America’s Deadliest DA.”

A 2019 report offers a possible policing explanation for why shootings are down nationally yet up here. The Trace, a nonprofit news organization focused on gun violence, found that low arrest rates for shootings in cities including Cleveland and Chicago correlated with higher rates of gun violence.

This could be happening in Philadelphia, where arrest rates in aggravated assault cases (the category that includes shootings) and homicides have both dropped since 2014 by a worrisome 14 percent. Recently resigned Philly police commissioner Richard Ross even acknowledged, last summer, that failing to make arrests can cause increased violence. McSwain, though, appears unmoved by any nuanced discussion of the reasons for Philly’s escalating gun violence. And he probably does believe Krasner’s policies are a disaster. But right now, his position isn’t based on data so much as ideology and anecdote.

In early November, for example, he issued another blistering statement about Krasner, saying his policies were responsible for the October shootings of two-year-old Nikolette Rivera, who died, and 11-month-old Yazeem Jenkins, who was gravely wounded. Specifically, McSwain said that Francisco Ortiz — who was charged with the shooting of Jenkins and is alleged to have supplied the gun used in the murder of Rivera — would not have been on the streets had Krasner’s office not agreed to reduced bail for him earlier in the summer. (Ortiz, who finished a 10-year prison term in April, was rearrested on gun possession charges in July.) Krasner, McSwain wrote, “is a defense-oriented ideologue who is more interested in looking out for the likes of Francisco Ortiz than he is in protecting public safety.”

Krasner’s response: “In an ideal world, there would have been an objection to the lowering of bail,” he says.

A native of West Chester, the 50-year-old McSwain was raised by Southern parents — his mom a native Virginian, his dad hailing from North Carolina. His father worked as a Protestant minister and later a counselor. McSwain graduated from Yale, then joined the military, where he served as a Marine platoon commander in the Persian Gulf, though he never saw any fighting. Returning to the U.S., he attended Harvard, earning a law degree before coming home to Pennsylvania and starting a three-year run as a line prosecutor. From there, he worked at top-shelf city firm Drinker, Biddle & Reath and took on successful fights in the 2000s to preserve a plaque bearing the 10 Commandments on the Chester County Courthouse and to protect the Boy Scouts’ right to exclude gay members.

The cases displayed a “collision” of constitutional rights, he says. Both times, he won. Over the years, campaign records show, he donated to Republican candidates, though there are no donations to Trump.

With his softer-spoken personality, McSwain will never be mistaken for the more mischievous Krasner. But since taking office, he’s made several national media appearances of his own, including on Michael Smerconish’s show, in a CNN segment with Don Lemon, and in three slots with hosts Laura Ingraham and Tucker Carlson on Fox. He also turned up at the annual Pennsylvania Society gathering, making the rounds of the state’s most powerful political players at their yearly soiree in New York.

“There’s no question,” says Larry Ceisler, the political and communications consultant, “that he seems to have political ambitions beyond his current job.”

The smart money is betting on McSwain to campaign as a Republican candidate for Pennsylvania’s next open U.S. Senate seat, and in this context, his public opposition to Krasner could represent both real disagreement and political expedience. In September, McSwain even appeared in federal court, arguing — again in a public dispute with Krasner — that a proposed safe injection site here is illegal.

Krasner has been vocal in declaring that the Safehouse project would be beneficial, providing on-site medical care for people using opioids that would help stem the city’s epidemic of opioid overdose deaths — 1,116 last year. The Justice Department intervened in February, filing a federal suit to stop Safehouse from opening. In an unusual move for a supervising attorney, McSwain argued the case himself.

As if in fulfillment of Krasner’s foretelling — “You will lose” — McSwain lost in court. The Justice Department promised an appeal, and McSwain has vowed to close the facility down if it opens before one is heard. But the truth is that — in the near term — there are only winners here. “Politically, being identified as the opponent of Larry Krasner is just great for Bill McSwain,” says J.J. Balaban, a political adman. “If he does intend to run for Senate, the fight with Krasner ups his appeal to conservative rural and suburban voters. That’s his constituency.”

And it’s symbiotic.

“Larry’s voters in Philadelphia see him being attacked by a ‘Trump appointee,’ and all they see is that first word, ‘Trump,’” says Balaban. “After that, nothing else that gets said matters. Krasner wins.”

It’s not entirely unheard-of for Philadelphia’s law enforcement officials to wind up at each other’s throats. Former AG Kathleen Kane and former DA Seth Williams engaged in a nasty feud that began with Kane’s decision not to go forward with a public corruption investigation. Kane and Williams, however, were ego-driven fellow Democrats who both wound up in jail for crimes committed in office.

Point being, it’s unprecedented, over the past 40 years, to see a fight among law enforcement so heated and all-encompassing as this. Both sides claim their staffs get along fine when they need to cooperate. But the bosses hate each other. McSwain says criminals call Krasner “Uncle Larry” because they know he’ll take care of them. Krasner created a slowly changing nickname for McSwain, calling him “15 months,” then “14 months,” etc. The numbers, counting down, reflect the slow turn of our calendar pages as Krasner ticks off the time till what he hopes will be Trump’s failed reelection bid and the installation of a new U.S. Attorney.

What remains to be seen is if this angry political moment will prove aberrant or the first days of a new normal. Not so long ago, voters retreated from politicians whose rhetoric turned nasty. Now, polls show, voters increasingly seek leaders who will fight for their values or even lash out against opponents. A survey published in April by the Georgetown Institute of Politics and Public Service Battleground Civility Poll showed voters trapped in an internal conflict: A unified 90 percent expressed concern with the “uncivil and rude behavior of politicians,” but big majorities (85 percent of Republicans, 69 percent of independents, and 78 percent of Democrats) indicated they’re tired of compromise and want leaders who will “stand up” to the other side.

The optics of two leading law enforcement officials in conflict are bad, but as Balaban puts it, “There is no real downside for either of them.” Krasner acknowledges that the feud helps them both politically. McSwain practically snorts at any suggestion he’s playing politics, saying he acts only “to keep Philadelphia safe.”

The most brutal assessment of McSwain’s role in all this probably came from Krasner’s communications director, Jane Roh, who tweeted over the summer that the U.S. Attorney is “so thirsty.”

The putdown, at once random and intimate, suggested she’d somehow stared through McSwain and seen his fluttering political ambitions — and also portends what we’re in for if Krasner does indeed run again and wins: years more of this, a battle in our backyard that mirrors the larger ideological war rocking this country.

For Josh Shapiro, an appearance at Netroots Nation, a convention for political progressives, was supposed to be easy.

Elected attorney general in November 2016, Shapiro, now 46, brought stability to a post besmirched by the arrest and conviction of former AG Kathleen Kane. He shaped the office with a new, activist bent, fully staffing a civil rights department and forming new units covering environmental protections and fair labor, to protect workers from abuse. He delivered, most famously, a comprehensive report on the history of child sex assaults in the Catholic Church, exposing more than 300 predator priests. And he has sued the Trump administration for alleged lawlessness 29 times so far, putting him at the forefront of the resistance movement that helped make Krasner a national darling.

In July at Netroots, Shapiro was slated for a panel called “Taking Trump to Court — and Winning.” When he tried to speak, though, protesters interrupted. “Yes or no! Yes or no!” they chanted. A new bill had just passed in Harrisburg granting Shapiro “concurrent jurisdiction” in Philadelphia, giving him authority to investigate gun crimes prior to any decision Krasner made about prosecution. Krasner framed the bill as an attempt by state legislators to “colonize” Philadelphia and a power grab for Shapiro, whose ambitions run to higher office.

“I didn’t ask for this law,” Shapiro pushed back in front of the protesters. “I don’t want this law; if the legislature wants to repeal this law, that’s certainly fine with me.”

On one hand, the dispute was hopelessly byzantine, featuring dupes, power plays, mischief and pure incompetence. The law was an amended version of earlier proposed legislation that would have given Shapiro the same authority throughout the state. That measure appeared to lack support. What DA anywhere wants to share authority with a state office? But a change stripping out every community in the state except Philly sailed through a House vote. The quick switcheroo was pure Pennsylvania — an opportunity for out-of-town legislators to stick it to Philly.

Attorney General Josh Shapiro. Krasner won’t comment on whether his wife, Judge Lisa Rau, might run against the AG next year. Photograph by Aimee Dilger/The Times Leader/Associated Press

Behind the scenes, says one Republican operative in Harrisburg who’s familiar with how that particular sausage link got made, Shapiro was uninvolved. The new provision targeting Philly was the product of legislators alone, with a particular push from Republican leadership. Shapiro’s Netroots performance might have set the issue to rest. But a month later, Krasner fumed about the episode to Clout, the Inquirer’s influential political column: “It’s a little like saying the guy stole your wallet and ran down the street. Is it over? No!”

There are natural managerial tensions between Krasner and Shapiro. Numerous attorneys Krasner fired or who quit rather than work for him found new employment with the AG. In the weeks after the concurrent-jurisdiction fiasco, that tension spilled into public view. The same week as the Clout column, Krasner was quoted in that Los Angeles Times article referring to the AG’s office as “Paraguay,” likening the old assistant district attorneys to Nazi war criminals.

There is also a deep political tension. Trump judges Republicans by their loyalty. Dems judge each other by their degree of wokeness, and Shapiro, from Krasner’s point of view, desperately needs more coffee. The two disagreed on safe injection sites (which Shapiro opposed) and the death penalty (Krasner filed suit to have it outlawed in Pennsylvania, while Shapiro says any changes should be left to the legislature). These are issues about which reasonable minds can disagree. And practically speaking, Shapiro’s statewide constituency would nudge him toward whatever remains of the steady center in our politics. These kinds of compromises, however, are anathema to Krasner, who appears to regard himself as the liberal dark roast to Shapiro’s moderate morning blend.

“He sees it all in moral terms,” says one of Krasner’s critics, a defense attorney who asked to remain anonymous to maintain a good working relationship with the office. “You either agree with him or you are deficient as a person.”

I interview Shapiro early in October in his office, finding him polished and mild. He wears his thinning hair shaved tight and sports minimalist silver-framed glasses. He declines to talk about his future political ambitions but shares his motivation for entering into public life, which sounds less revolutionary than Rockwellian: His mother was a Montgomery County schoolteacher. His father is a pediatrician. “I always understood the importance of public service,” he says.

Destined by his DNA to play the adult in the room, Shapiro handled the “Paraguay” controversy with particular aplomb, defending his staff in an internal email that, predictably, leaked, allowing him to take a public stand without engaging Krasner in open warfare.

The strategy looked canny and wise to political advisers like Balaban, who note that Shapiro’s political ambitions are well understood: He has an eye on higher offices, particularly the governor’s seat. “If he wants to run for governor,” Balaban says, “he will need Philadelphia’s progressive voters. Getting into a fight with Krasner is just not in his interests.”

At least initially, and after meeting McSwain and Krasner, I find spending time with Shapiro a relief, like visiting Switzerland during the war. But his plight underscores the challenge any Democratic politician faces today. In an age of litmus tests, there is little room for compromise and restraint. He refuses to engage in any negativity about Krasner or McSwain, saying, “I’m not going to get into any of my private conversations with any other law enforcement leaders.” He also typifies his relationships with both men as “productive,” adding, “I deal with 67 regional DAs and three U.S. Attorneys.”

These are classic quotes from Shapiro — so soft on the surface as to appear unremarkable. Parsed carefully, however, they’re his version of a vicious haymaker. Not discussing private conversations with other law enforcement officials is an adult, responsible way to handle conflict among colleagues. Saying so is a way of flatly rejecting the performative swagger Krasner and McSwain bring to their jobs, branding both men as unprofessional without enflaming the situation by using the word.

Similarly, pointing out just how many U.S. Attorneys and DAs work in Pennsylvania reminds us all that of these three guys, the one with the widest kingdom is named Josh Shapiro. Again, canny — or at least, it would have been in 2005. But do these centrist politics work now?

In the midst of my interview with Krasner, his cell phone lights up with a call. It’s Josh Shapiro. Krasner just lets it ring.

At this point, the rivalry between Shapiro and Krasner is only sort of over. Krasner has refrained from publicly blasting Shapiro for a couple of months now. And Shapiro never engaged. Krasner even told me his relationship with Shapiro was “improving” — that a new chapter had begun. But when Krasner’s wife, Judge Lisa Rau, announced a surprise retirement from the bench at 59, a rumor surfaced that she would run against Shapiro in his 2020 reelection bid for AG. During our interview, I ask Krasner if that’s her plan.

“No comment,” he says, making no effort to suppress another gleeful, devilishly self-satisfied smile. Whether the smile sends a message that she will run or reflects Krasner’s joy at causing such turmoil for Shapiro is unclear.

That same afternoon, in the midst of our interview, his cell phone lights up with a call. It’s Shapiro. Larry Krasner just lets it ring.

In June, some of Shapiro’s staffers held an off-the-record conversation with an Inquirer reporter and bantered about it afterward via email.

“Low bail, withdraw [sic], further downgrading of charges, ineffective prosecutions and ultimately very low sentences allow violent offenders to be on the street increasing crime and shootings/homicides,” wrote chief deputy attorney for gun violence Brendan O’Malley.

“I think [the Inquirer] and their team will try to get at that next,” Joe Grace, then the AG’s press secretary, wrote back. “That’s what our call did for them, one would hope.”

In the context of the ongoing drama among the state’s highest-profile law enforcement officials, the emails, revealed in a story published by the Intercept, provide a glimpse of the politics involved. McSwain and Krasner, the partisans, favor frontal attacks. Shapiro must plot a more careful course through the dark, and from the rear.

In past years, Shapiro most likely could have counted on overwhelming political support from the Democratic Party machine. Krasner is still regarded as a party outsider, an insurgent candidate the Dem establishment would shiv if it could. This doesn’t mean he lacks any support from fellow elected officials. State Reps Chris Rabb and Donna Bullock respond to interview requests promptly. Rabb is effusive in his praise for Krasner. Bullock is a shade more circumspect, walking a careful line by saying, “I think Larry Krasner is doing a good job, and there is always a challenge in striking the right balance between justice reform and public safety.”

Council President Darrell Clarke declines to be interviewed for this story, however, and Councilmember Maria Quiñones Sánchez never responds to an interview request. And Allan Domb, the guy who raised his arms in apparent triumph last April when Krasner testified to how much money he’d saved the city? He doesn’t want to be interviewed, either.

“I think,” one Democratic power player tells me, requesting anonymity, “that for a lot of people, there is no benefit to being associated with [Krasner]. In any respect.”

Praise him, and come under fire from his enemies. Criticize him, and face his angry partisans.

Better, perhaps, just to stay away.

All the political operatives and pundits I speak with believe that Krasner, if he chooses to run for reelection, is placing a solid bet on the strength of his political base to win the next Democratic primary. A successful challenge would require a small Democratic primary field — ideally, Krasner and one opponent. The danger for Krasner would grow, exponentially, if the challenger were female, which would energize primary voters. The lane for such a candidacy would be narrow, involving a promise to retain the greater share of Krasner’s reforms while reverting to a tougher stance on guns and crime.

While Krasner’s wife is rumored to be looking to challenge Shapiro, the name that keeps popping up for challenging Krasner himself is Democratic State Representative Joanna McClinton. According to one state political operative, McClinton — a lawyer who spent seven years in the public defender’s office — has already been encouraged to consider a run.

McClinton, meanwhile, seems to be keeping her options open and not to be particularly interested in taking on the DA. “People have approached me about running for a few different offices,” she says. “However, I remain focused on my constituents in the 191st District and on advancing criminal justice reform throughout the state, by legislation.”

The issue, say political observers, is that any effort to unseat Krasner would require the “giants” he speaks of to demonstrate a level of party control they no longer have. Just 10 years ago, the Democratic Party might have organized the storm clouds surrounding Krasner into a hurricane. But the days when Vince Fumo, in the state Senate, or Bob Brady, the head of the local party, could clear a field of unwanted candidates by offering some carrot in return are gone.

In a million ways, the demise of backroom Philadelphia politics is an absolute good — an end to having our leaders chosen for us in the dark.

But for those who would like to see Krasner ushered out the door, it’s doom — and he promises a broader revolution to come.

His candidacy, he says, provides a template. The voters he’s brought into the system comprise a new political base for others to court. This is evident, already, in how Reclaim Philadelphia — the first grassroots organization to back Krasner — continues to accumulate power. One year after Krasner’s election, Reclaim backed Elizabeth Fiedler, an insurgent running against the Democratic Party’s preferred candidate, in a successful bid for South Philly state rep. Now Nikil Saval, a co-founder of Reclaim, has launched a run for state Senate.

The implications of all this are clear: Shapiro holds the bigger office. But Larry Krasner is at the center of a political movement. Cast into the 2020 Democratic presidential primaries, Krasner would slot alongside Elizabeth Warren (whom he endorsed in late October) or Bernie Sanders. Shapiro? Joe Biden. A swell guy of some earlier hour.

Toward the end of my interview with Shapiro, I bring up the power of female candidates in today’s Democratic party and ask: Are you afraid of Larry Krasner’s wife?

Shapiro tosses his head back as if he’s been struck and laughs.

“I’m not gonna answer that,” he says.

Perhaps, here, he might deliver some polite but firm statement of self-confidence. But it’s hard to look dignified when there’s an octopus on your face. And so he just repeats: “Ask her about that. Ask her about that.”

Last summer, Shapiro’s governmental affairs coordinator, Mike Vereb, sent an email of warning to a fellow staffer: “This is not going to end well during the summer. Phila gun violence and Krasner are a topic of conversation in the Oval Office. I am directly aware of a meeting Friday on this topic. Unfortunately I am not aware of the results. But for some reason Trump is focused on this.”

“Yep. Agreed. Going to get worse,” his colleague replied.

Krasner’s sense of himself as an awakener of “giants” might sound quixotic at first. But there is no bigger giant in American politics than an American president. And Trump appears to have taken an interest in our district attorney.

The good news, for Krasner, is that he has accumulated a lot of experience at defending himself. The plays made on his throne are so numerous that some of them even escape public notice.

Last summer, police started informing people in the Kensington-Port Richmond neighborhood that Krasner wasn’t charging people they arrested. In response, Krasner developed a whole report and presented it to the community, proving his numbers were in line with those of his predecessors. “When an arrest is made,” says Krasner, “we bring charges as often as anyone else.”

At a public meeting in Nicetown after last summer’s police standoff, a pair of officers were about to take the podium and misinform the crowd that the alleged shooter, Maurice Hill, was only on the street because of a deal Krasner had given him on a prior case. The same story had been floated and debunked days earlier. But these cops were going to repeat it anyway, bringing the pure propaganda and gaslighting that constantly emanate from the White House back home.

“One of our investigators,” says Krasner’s press aide, Roh, “stopped them before they could go on and said, ‘You can’t do that.’”

Crisis averted. But there will always be another crisis coming. And another. Because Krasner really is a target — of everyone from local forces on the ground, like police union president John McNesby, to the U.S. Attorney and the White House. So the question looms: Will Krasner, with all this resistance to his resistance, even run?

“Oh,” says Krasner, taking a moment to theatrically pull at his shirt cuffs and straighten the knot in his tie, “I’m gonna run again. I like it too much. I got so much done, and now — I get to fight the giants.”

There’s a pause, and then he adds, slyly: “Who wouldn’t want that?”

He chuckles, expressing the gallows humor of a man who spent his career in criminal courtrooms. “People,” he says, “got their urges.”

* This post has been updated to clarify the scope of the DA’s office’s bail reform practices.

Published as “Krasner’s Wars” in the December 2019 issue of Philadelphia magazine.