If Opioids Are a Public Health Crisis, Let’s Admit the Crack Epidemic Was Too

Black and brown people were criminalized for the same type of addiction the city now proposes to treat — and city government needs to atone for that neglect.

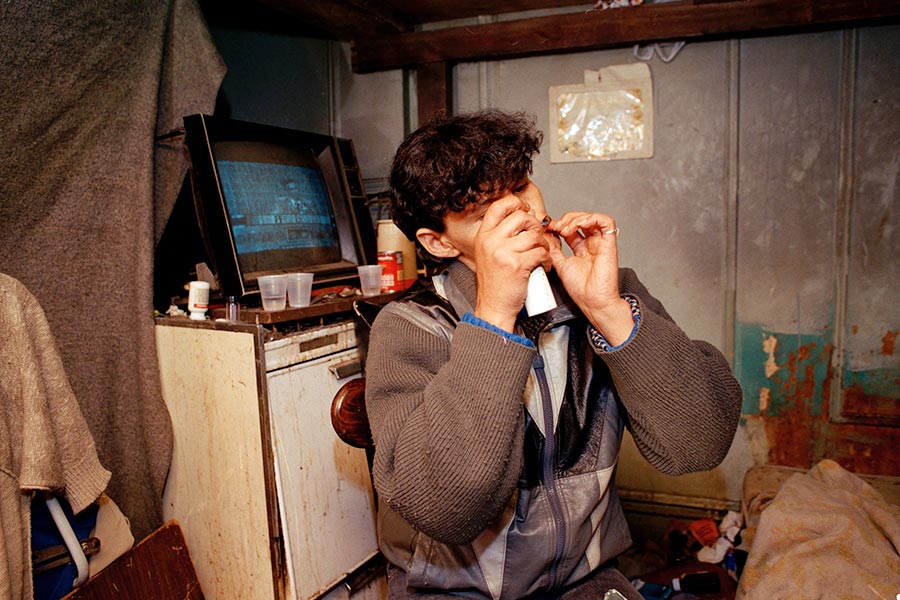

An unidentified woman smokes crack in New York, 1990. (AP file photo)

Growing up, I was taught that people addicted to drugs were criminals who should be jailed for their poor judgment.

This was in the ’90s, a decade after the start of a “Just Say No” era in which a disproportionate number of Black and brown citizens were arrested for possession of crack cocaine. The crack epidemic was treated as a national embarrassment that could be cured only through mass incarceration. These excessive punishments put a generation of Black men and women behind bars, destroying families and devastating urban communities — and in reality accelerating the poverty and crime the laws were meant to combat.

Cities like Philadelphia continue to live with the effects of this flawed response to drug addiction. According to federal crime statistics, Black people currently comprise only 12.5 percent of regular drug users, but are 33 percent of those incarcerated for drug offenses. This disparity was even worse during the mid-1980s through late 1990s, according to a Harvard study measuring city “crack levels” (based on “cocaine arrests, cocaine-related emergency room visits, cocaine-induced drug deaths, crack mentions in newspapers, and DEA drug busts”): Philadelphia was ranked the fourth highest, behind Atlanta, San Francisco, and Newark.

In the midst of the crisis, Pennsylvania lawmakers from both sides of the aisle advocated for tougher laws, such as enforcing strict mandatory minimum drug sentences, that adversely penalized Black crack addicts. It would not be until 2010, when Congress passed the Fair Sentencing Act (FSA), that such sentencing disparities between crack and powder cocaine offenses would drop from 100:1 to 18:1. (Prior to FSA, Blacks were serving nearly as much prison time for nonviolent drug offenses as white people did for violent offenses.)

Contrast these sobering facts with all the efforts currently under way to tackle opioid addiction — the deadliest drug overdose crisis in history. This time around, the victims are disproportionately white, and public sympathy has suddenly shifted: What was once declared a “war on drugs” is now being reframed as a “public health crisis.”

At the same time, our city is finally coming to its senses and holding other institutions accountable. In mid-January, Philadelphia joined more than 200 cities around the country in suing opioid manufacturers, whom they hold partially at fault for the overdose crisis. Last week, the city announced plans to become the nation’s first safe injection site, estimating that such a facility could save 76 lives a year. “We cannot just watch as our children, our parents, our brothers, and our sisters die of drug overdose,” Philadelphia health commissioner Thomas Farley said in a statement. “We have to use every proven tool we can to save their lives until they recover from the grip of addiction.”

I rejoice in the progress being made in Philadelphia’s response to drug addiction, but it’s nonetheless bittersweet. As I witness the growing compassion for the mostly white victims of opioids, I still mourn the deaths of thousands of Black and brown people from crack overdoses and the survivors who remain behind bars serving unfair sentences on nonviolent drug charges. If only they had had a safe site and a local government who empathized with them — imagine how Philadelphia might have turned out.

We cannot change the past, but we can vow to right its wrongs. Although Mayor Kenney cannot formally pardon the countless victims of our local and national criminal justice systems, he should formally apologize on behalf of the city to everyone who was penalized by the crack epidemic. This city cannot truly make history in the treatment of addiction if it does not atone for its past failings.

I will never forget how affirming it felt when Congress formally apologized to Black Americans in 2008 for its role in Jim Crow injustices and slavery, becoming the first branch of federal government to do so. Shortly after, states also began to pass resolutions apologizing for their past actions. While such gestures might seem merely symbolic, they establish a tangible baseline for how our country should treat those it once oppressed.

And for the future? Perhaps the city could model further redress on the way San Francisco will now retroactively apply California’s marijuana-legalization laws to past criminal cases. Or maybe Kenney should back State Rep. Jordan Harris’ proposal to erase marijuana convictions for registered patients. Until that day, history shouldn’t continue to simply write off crack’s victims as criminals who made poor decisions. They deserve the vindication of empathy that a majority of white drug users are experiencing today.