Do They Still Make Republicans Like Tom Ridge?

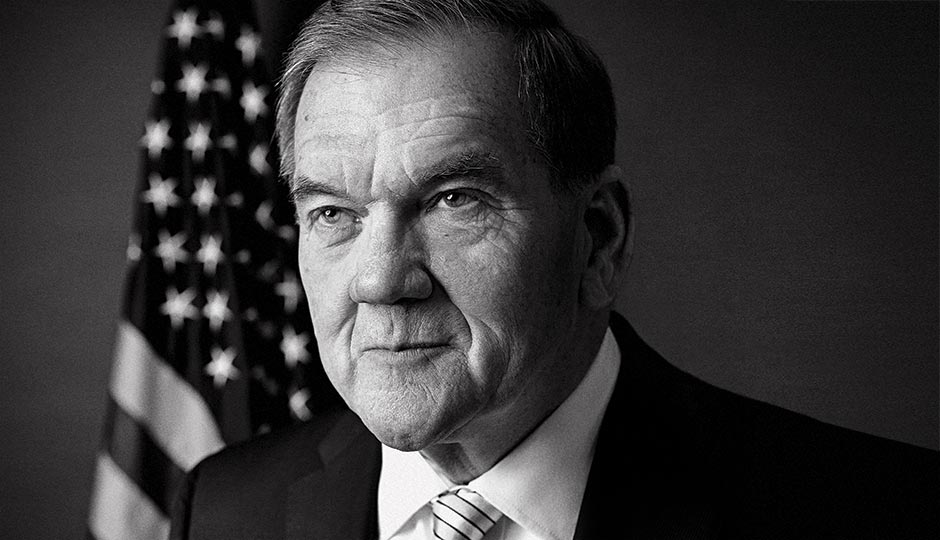

Tom Ridge. Photograph by Matt Stanley

On election night, as the foreign country around him lay sleeping, Tom Ridge stayed up all night, watching TV. “I wanted to know who my president was going to be,” he says.

Ridge was all alone in a hotel room in the Ukrainian capital of Kiev, and he felt surprised but not shocked when the race was called in favor of Donald Trump. Ridge is a former military man and former governor of Pennsylvania — he viewed the crash site at Shanksville on 9/11 — and served as the nation’s first Secretary of Homeland Security. He’d been prepared for Trump’s victory by a trip he’d made back home, to Erie, prior to the election.

“I’d never seen that level of engagement and support,” he says, “for any presidential candidate.”

The lawn signs, bumper stickers and billboards seemed to speak of near-unanimous intention, so Ridge, his hotel TV turned to CNN, felt no knot in the pit of his stomach. “I switched modes immediately,” he says. “It was just, ‘Okay, now Donald Trump is my president. I want him to succeed.’”

Back in May, Ridge, a Republican, had penned a guest column for U.S. News & World Report announcing that he wouldn’t vote for Trump or Clinton. “His bombastic tone reflects the traits of a bully,” he wrote, “not an American president and statesman. If he cannot unite Republicans, how can he unite America?”

Today, Ridge says, with surprising enthusiasm, “I’m rooting for Trump.” He cites some of the cabinet picks — Kelly in Homeland Security, Mattis in Defense, Tillerson in State — and says, “I have to give him credit where credit is due.” But he hasn’t changed his head or heart. In fact, Ridge is still waging a carefully calibrated campaign of his own. He is pushing, he says, with a pause and a single crisply enunciated word, for “civility.”

On its face, the 71-year-old Ridge’s mission might appear both laudable and laughable. The news each day is rife with conflict: Protesters decry the President’s policies and overblown, dictatorial methods; each morning, seemingly, Trump hits “send” on some toxic tweet, leveling unsubstantiated claims of voter fraud and “paid” agitators, even that the previous president tapped his phones. His approval rating is at a record low for any president at this early stage of his administration — roughly 40 percent. But who cares? That’s just most of America. The same polling shows at least 85 percent of Republicans think he’s doing fine.

In this fiercely partisan environment, Ridge seems anachronistic. The first time I interviewed him in his D.C. office, he described bipartisan compromise as “the heart of democracy.” Around that time, Republican leaders in Congress were declining to launch an independent investigation of Trump’s possible ties to Russia, a foreign power, with GOP Senator Rand Paul even admitting the effort would distract them from pursuing their partisan agenda.

Do they even make Republicans like Tom Ridge any more?

Of course, the need to ask this question captures why Ridge’s out-of-step ideals are so important right now. “If we have this politics of division and demonization, it doesn’t seem to me that there’s any way forward for a democracy under those conditions,” says Ridge, “and so because I love my country, I’m advocating that we restore civility to our discourse and treat our opponents with respect.”

Ridge’s opening salvo, perhaps out of an overabundance of politeness, is larded with a gentle euphemism, its concussive conclusion made purposefully indirect: What does it mean when he says our current division permits “no way forward” for democracy if not that on its current course, America will cease to be a democracy at all? And so the first man to represent our Department of Homeland Security is back, bearing an urgent message: Our homeland isn’t so secure.

Tom Ridge remembers the dinnertime conversation most. His parents engaged in long discussions about politics — and disagreed about pretty much everything. “What I remember is the tone,” he says. “There wasn’t any yelling.” The debates between his mother, a Republican, and his father, a Democrat, evolved like a tennis match in which “neither player was interested in scoring a point.”

Today, Ridge serves as CEO of a self-named company, Ridge Global, that consults with corporations on matters of cybersecurity and risk management. He splits time between D.C., where his company is headquartered, and Erie. But work takes him all over the world. He might be in Ukraine one week and Dubai or London another. But he remains very much the product of Erie — a small city closer to Cleveland than to Philadelphia — and his parents’ bipartisan dinner table.

As he grew, his life took turns that would satisfy both right and left, checking boxes associated with Republican and Democratic candidates. He served in Vietnam as a staff sergeant, long a conservative credential, without seeking any deferments or way out. He graduated from Harvard, that bastion of liberalism, with a degree in government studies. He served six terms in Congress in an era when Republicans and Democrats actually compromised. And when he ran for governor in 1994, the Daily News description that became his unofficial slogan — “A guy nobody ever heard of, from a city nobody’s ever seen” — marked him as a politician with the humility and good grace to turn even his weaknesses into strengths.

“I think Tom’s decency was always apparent,” says former governor Ed Rendell, who worked with Ridge when he was Philly’s mayor. “There was never any sense with him that political party identifications were driving him. My mayoral administration enjoyed a great partner in him.”

Ridge’s old gubernatorial spokesman, Tim Reeves, was surprised when the administration approached him, back when he was a reporter for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, about serving as press secretary. Sheepishly, he told chief of staff Mark Holman: “Do you realize I’m a registered Democrat?”

Holman rolled his eyes. Reeves got the job. “As we talked about position requirements and sifted through candidates for various jobs,” says Holman, “the Governor never once asked about anyone’s politics. So I knew it wasn’t important to him.”

Ridge was, by seemingly all accounts, a personally happy and professionally productive governor. He even prefers to be called “Governor” today, rather than “Secretary,” his last and highest-ranking position. While leading Pennsylvania during the Clinton go-go years of relative prosperity — a distinct advantage — he oversaw a boom in charter schools, steered Pittsburgh and Philadelphia through contentious debates over sports stadiums, and brought shipbuilding back to Philly at the Navy Yard.

In Congress and later as governor, he watched other politicians live and die with every vote. But he had seen real life-and-death crises, close up, in Vietnam — “Being shot at gives you a new perspective,” he says — and recognized the difference. He had about 16 months left as governor on 9/11. Then President George W. Bush, also a friend, called and asked him to help design and implement the nation’s post-9/11 security strategy, ultimately forming the current Department of Homeland Security.

Ridge’s gubernatorial staff put together a fast but comprehensive study of the position’s pros and cons, but Ridge never heard it, waving them off. The president’s call, for him, was like Vietnam: He didn’t particularly want to go, but a sense of duty compelled him.

Ridge quickly became a target for late-night comedians. The nation’s new terror watch system, which included color-coded “threat levels” ranging from green (low) up through blue, yellow, orange and red, quickly proved alarmist and self-defeating. When the threat kicked up to blue or yellow, how could Ridge dial it back? Wouldn’t he be blamed if the drop preceded an attack?

Citizens also didn’t know what was expected of them — how should we behave on a yellow day as opposed to a green one? At his nadir, Ridge suggested citizens invest in duct tape and plastic sheeting as a hedge against possible bio-weapons attacks. Some panicked citizens quickly bought out all the available stock at local hardware stores and sealed their homes in plastic. Clearly, Tom Ridge had a lot to learn in his new role. What saved him is that the “guy nobody ever heard of” was humble enough to admit as much.

Our current president flips out after most episodes of Saturday Night Live. But when comedians made fun of Ridge — one night, SNL famously declared the threat level magenta, just shy of oxblood — he never took it personally. He even laughed about the jokes during media interviews, and told some himself.

Ridge served for about a year in a poorly defined advisory role before winning unanimous confirmation from the Senate to a new cabinet-level position. His ascension marked a moment of American unity, never mind the fractures in our foundation. He became the calm face of America’s response to terror.

The “no win” job, against all odds, became a big victory, and in 2004 Ridge retired from the role. He’d often been rumored as a VP candidate; would he run for president himself? But just a dozen years later, every political professional I interviewed for this story made the same observation: Tom Ridge would have a very hard time getting elected today. For the House, Senate, governor, president, maybe even school board.

Ridge, long a pro-choice Republican — “I think the decision is best left between a woman, her doctor and her God,” he says — further undermined his ideological purity by going pro-gay marriage. As governor, Ridge signed a state defense of marriage act in 1996, defining marriage as occurring only between a man and a woman. But years of meeting gay and lesbian people and getting to know them as colleagues and friends caused him to “evolve.” And evolution on these kinds of core ideological disputes is something our current politics don’t allow.

“I like Tom Ridge, I really do,” says Republican pollster Frank Luntz. “But there’s no question he’s out of step with what the primary voters in the Republican Party want, which is someone far more ideological. I don’t think he could get elected in this environment.”

Do they make Republicans like Tom Ridge any more? “The short answer,” offers SiriusXM talk-show host Michael Smerconish, “is no.”

Smerconish and Luntz both consider Ridge’s electoral obsolescence a sign of danger for the Republican Party and perhaps even the nation as a whole.

“There’s no question we have reached a crisis point,” says Smerconish. “We have to learn how to talk to each other again, across party boundaries, ethnic and racial boundaries and regional boundaries.”

Luntz, whom I interviewed in February, says our politics are racing toward a new bottom. “I can see it in my own data,” he says. “The hostility, the anger! You can see it grow from the primary to the election, and then it jumped again by the inauguration, and it’s worse now. Every month you can see it get worse.”

Among Republican voters he polled on Election Day, just 35 percent wanted to see any kind of bipartisanship from their elected leaders. And this was before they knew the results. “It’s a rejection of compromise, and it undermines the democratic process,” says Luntz, “and it’s going to get a lot worse before it gets better. I believe this year will resemble 1968. My hope, and this is the best I can ask for, is that the similarity is in the tone and extent of protests, not in the matter of lives lost.”

Does he see any sign of hope? “Not much,” says Luntz. “If you want some hope, at least we still have examples, like Tom Ridge, that there is a better way to do things. But I have to admit: I’m not very hopeful.”

This past summer, Tom Ridge attended a ceremony in Washington, D.C., where he presented the Allegheny College Prize for Civility in Public Life to both Senator John McCain and Vice President Joe Biden.

Standing there in a conservative blue suit, before a pair of American flags, Ridge spoke on behalf of the award’s founding institution, Allegheny College, a small liberal arts school in Meadville, Pennsylvania. He struck all the right notes, talking about the need for the cross-party friendship Biden and McCain maintain and, of course, for their civility. Ridge, and the Allegheny College prize, seems to define civility broadly, encompassing polite behavior, courtesy, respect and consideration. This last word captures the essence of bipartisanship — that opposing viewpoints should be considered and to some degree accommodated as a matter of course. But the whole affair seemed to convey sadness, even isolation — a gathering of adherents quietly celebrating a niche faith.

Allegheny College, a campus of 2,000 students in a community of just 13,000, wouldn’t normally be expected to hold annual events that earn national coverage, but the Prize for Civility is becoming kind of a thing, sparking stories in USA Today, the Los Angeles Times and Time magazine. Allegheny College president James Mullen says Ridge has been vital: “To be straightforward about it, he is obviously key to even getting figures like Vice President Biden and Senator McCain to attend.”

But far from merely attending the ceremony, Ridge also goes to regular meetings to discuss potential winners and strategize promotions and events. This year, Ridge highlighted one key moment from the career of each award winner. He lauded Biden, whom he referred to as “my vice president,” for the speech he gave in October 2015 in which he announced he wouldn’t run for president. “We are opponents, not enemies,” Biden said, calling for a change in the tenor of politics.

Ridge also celebrated John McCain’s famous “No, ma’am” moment, when a woman at a town hall for McCain’s 2008 presidential candidacy questioned Barack Obama’s citizenship and called him an “Arab.”

“No, ma’am,” McCain gently responded. “He’s a decent family man, citizen, that I just happen to have disagreements with on fundamental issues, and that’s what this campaign is all about.”

Ridge portrayed both instances, both men, as candles glowing in the current dark. And he brought tremendous gravitas to the task. His face, though jowlier than during his time as governor, remains chiseled, seemingly made for regular public viewings. He is also six-foot-two, with a still-youthful vitality. But that sense of a shrinking cult — Mullen, Ridge, Biden and McCain all spoke about civility as a kind of fugitive on the run — never lifted.

Some words do provoke a kind of automatic harrumph in our irreverent age — civility, etiquette, politeness. Mullen admits he frequently hears criticism that the prize honors something no longer of value. “I hear that a lot,” he says. “‘Civility is over,’ ‘Civility is dead,’ and ‘Civility doesn’t get things done.’”

Ever civil himself, he declines to call out any critics by name. What alarms him is that these critics are otherwise “good, respectable people.” Their rejection of decorum further convinces him “that we’re doing something important, and we need to work that much harder at it.”

The effort did gain a new urgency this past year — and not just because of the election. During one of our interviews, Ridge nodded along as his press agent, Steve Aaron, quoted from memory the “concerning” details of a 2016 study Mullen and Allegheny College commissioned through the Zogby polling firm. The most alarming stat: The percentage of voters who believe elected officials should pursue personal friendships with members of other parties plummeted from 85 percent in 2010 to just 56 percent.

Ridge’s response to this shift is, as ever, well-meaning. He works, gratis, on behalf of the Allegheny College prize. He wrote about civility in a guest column for Time. And whenever he encounters a member of the House or Senate, he finds a moment to engage on the subject.

Still, in this divided climate, isn’t any effort to promote civility doomed to failure? Isn’t Tom Ridge, the old soldier, trying to stop a hurricane by blowing a kiss into its howling winds?

“I don’t know what I can say,” says Ridge, “except that I am doing everything I can, and I am going to keep pushing.”

Last August, Donald Trump brought his campaign to Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, the kind of white, working-class town that would eventually propel him to victory. Trump had just taken considerable heat for insulting Khizr and Ghazala Khan, Gold Star parents and Muslims who lost their son, a U.S. Army captain, when he was fighting for America in Iraq.

Nonetheless, Trump and his surrogates served up generous portions of political red meat, triggering chants of “Lock her up!” and “Build that wall!” He castigated the media, cordoned off at the back of the Cumberland Valley High School gym. And he won the crowd by telling them about a meeting he’d had with a group of coal miners in West Virginia, relating their plight to that of laid-off factory workers throughout central Pennsylvania.

“I asked them, ‘Did you ever think of maybe moving and going into a different business?’” he said.

The coal miners said they didn’t want to move. They wanted to stay where they’d been born and work the jobs their parents and grandparents had. Trump told the crowd he understood, respected, the coal miners’ argument, and in response he was going to bring those jobs back.

Of course, his promise is denounced by experts on both the right and left as impossible to keep: The coal industry is being destroyed by the free market, not regulation; natural gas is more abundant and cheaper to obtain. And manufacturing jobs have been reduced because of technology. Robotics are replacing less precise, and more expensive, human workers. But there is a lesson to take from this moment that goes beyond Trump’s lack of understanding of, or disregard for, the true drivers of the American economy.

The average Trump voter has largely been depicted as racist and uneducated. And yes, race did play a significant role. What, 58 percent of white voters preferred Trump while 88 percent of African-American voters chose Clinton for no reason? Further, Trump did perform much better with voters who lack a college degree. But any insistence on seeing all his supporters through a prism that is both narrow and pejorative won’t do anything to woo such voters next time, or bind this country’s cultural wounds.

Put another way: A large swath of white America feels it’s been mistreated. Will any argument convince them to feel otherwise?

Ridge’s old press secretary, Tim Reeves, tells a story about what it was like for him, as a Democrat and former reporter, to become privy to what Republicans said in private. “They took me, because of my position, to be one of them,” he says. “And while I didn’t normally agree with their criticism of the media, I did come to realize that these were very thoughtful Republicans, and their sense of being truly aggrieved, that the media just will not give them a fair shake, was real. It isn’t just a campaign tactic. They really feel wounded by it.”

From Reeves’s perspective, what to do about the problem is difficult to calculate. The new administration — and Congressional conservatives — shouts “fake news” every time a new and damaging fact is reported. But Reeves insists that accepting the reality of this sense of “injury” among rank-and-file Republicans is crucial to genuine understanding: “It colors all their perceptions of whatever the media reports.”

Of course, this cuts both ways. The media, right and left, has been engaged in a kind of arms race. Fox triggered MSNBC. Big right-wing personalities like Rush Limbaugh and Bill O’Reilly were countered by Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert. Both Stewart and Colbert emerged as, foremost, satirists, riffing off of provable facts. But in terms of our current cultural divide and separating right-wing rurals from left-wing coastal elites, did they help?

“No,” says Reeves. “They didn’t.”

Ridge looks back at the media and entertainment industry’s treatment of George W. Bush as one of many drivers that led to where we are now. “He wasn’t, and isn’t, stupid,” says Ridge, and he shares a quick story to make his point.

One day Ridge joined Bush and a team of advisers in the Situation Room. They had what appeared to be solid information about pending attacks on multiple planes flying into the United States from various overseas locations. Bush moved the discussion around the table, hearing out each adviser’s opinion on the seriousness of the threat and the credibility of the intelligence. “The review he got was mixed,” says Ridge. “There was no real agreement about what we should do.”

In response, Bush offered a brief smile. He said he appreciated everyone’s input. And he offered up one question he wanted everyone at the table to answer: “How many of you would put your family on one of these planes?”

Ridge, in his D.C. office, looks around, a bewildered expression on his face, mimicking the advisers gathered at the table, all sitting in silence. “He was like, ‘Okay, I guess we have our answer,’” says Ridge.

Ridge’s point seems obvious: Bush wasn’t a dummy, and in fact possessed a deft emotional intelligence. But the media characterization of him as stupid helped precondition conservatives to reject any negative media narrative about their icons.

For all his bipartisanship, Ridge remains a “true” conservative in most respects. He is disdainful of Obama’s foreign policy, which he calls “nonexistent.” He remains an advocate for charter schools — eager to see the results-driven free market provide solutions for America’s education woes.

But in direct contradiction of Trump’s attacks on the media, Ridge says, “There is no such thing as an alternative fact. … The free press is absolutely vital, a cornerstone of democracy. I don’t want to be overly dramatic, but who the hell wants to live in Russia? Without a free press? If you take the free press away, it’s not a democracy.” Still, he fears the line between entertainment and the New York Times has been blurred — that to many viewers and readers, Stephen Colbert, Hollywood and Times editor Dean Baquet are all reading from the same hymnal.

“It’s a difficult problem,” says Ridge, “because we can’t, and shouldn’t, police the entertainment industry. But there needs to be some understanding, on both sides, of how we treat each other.”

There is, of course, a problem of false equivalencies. Trump’s fat-shaming and Mexican hating, his treatment of women and his threats to reinstate torture, murder terrorists’ families and steal Iraq’s oil, really are far worse than Hillary Clinton’s most notorious slip, when she referred to Trump’s supporters as a “basket of deplorables.” But Ridge says the current moment requires us all to be sticklers for civility — that restoring American politics to the high road of civil debate about issues, not personalities, requires both sides to be on that road all the time.

“I was very disappointed when she made the ‘deplorables’ remark,” says Ridge. “And believe me, I hear about it from my Republican friends.”

As Luntz, the Republican pollster, told me, “The right’s current hatred of the media is so great” that conservatives are likely to reject all arguments, and evidence, against Trump precisely because they can’t stand the messenger. And Tim Reeves agrees. Trump’s flirtation with white nationalists, his late, tepid response to the violence rising up in the wake of his policies, his ties to Russia — none of it seems to be making a significant dent in his popularity with the Republican Party’s new, more extreme base. It’s as if they can’t allow the left, or the media, to get any kind of “win.”

The current dynamic, then, is so dysfunctional that the only victories are zero-sum — total victory or none at all. And so the biggest question of all is put to Ridge: Is this political moment like Vietnam and his stint at Homeland Security? Is this moment about life and death?

“I’d like to be optimistic,” says Ridge, “because I am an optimist by nature. … ”

Ridge pauses then, considering his next words, but nothing to justify any optimism comes.

On day 27 of the Trump administration, just two weeks after he first told me, “Donald Trump is my president, and we need to give him a chance,” Tom Ridge is eyeing his own personal event horizon, the moment when he might be moved to act, to break his recent public silence on Trump and speak out.

The previous 72 hours kicked the national angst meter up to code red for Russia, and Ridge wasn’t immune. Trump’s national security adviser, Michael Flynn, was revealed to have spoken with Russian officials about sanctions imposed by the Obama administration prior to taking office. He subsequently resigned. Another story declared that U.S. intelligence officials had discovered the Russia links went well beyond Flynn: Multiple members of Trump’s campaign team had been in touch with Russian intelligence officials throughout the 2016 presidential race.

These events and Trump’s reaction to them aroused widespread concern: Did Flynn hold these conversations with Trump’s approval? Just why is Trump able to criticize or threaten every pillar of American democracy — presidents, legislators, the military and intelligence services — but not his buddy Vlad? Yet Congressional Republicans had again indicated that they wouldn’t allow an independent investigation, and Ridge was incredulous.

“Forget Mike Flynn, and forget President Trump,” he says, trying to remove personalities and partisanship from the equation. “This is about the pillars of our government. This is about rallying around the flag. A foreign power hacked into the DNC to try and sway the results of the election? There is some kind of tie, potentially, between a foreign power and one of our presidential campaigns?”

He sits forward in his chair. “The election process is the pillar of democracy,” he says. “This goes beyond party. No foreign power can be allowed to interfere in that. … This should be a bipartisan effort involving both the House and the Senate. I’m going to stay quiet for now, but I have my limits.”

There are those who believe his words might yet matter, a lot. “I think a lot of people held their noses when they voted for Trump,” says Stuart Stevens, a strategist for Mitt Romney’s 2012 presidential run. “His support is likely not so great as it seems.”

There “might” come a time, says Stevens, when criticism from more mainstream Republicans like Ridge or Romney will ratchet up opposition.

Closer to home, Sam Katz, who lost to Ridge in the governor’s primary race in ’93, agrees and goes further. “Tom Ridge is very smart to spend some time on the sidelines right now,” he says, “and knowing him, I’m sure he will identify the right time, if there ever is one, to speak up. When and if he does, he will provide cover for a lot of other Republicans to act.”

The Trump administration, then, could be the flash point around which mainstream Republicans and Democrats ultimately unite. And if that happens, perhaps we can start talking to each other again. “I do think there is a possibility that Trump could be the trigger that causes some positive change,” says Smerconish. “But it’s going to take a lot of work.”

Even now, the current sense of crisis might actually be unifying political forces that usually define themselves in opposition to each other. Just a decade ago, Tom Ridge was one of the nation’s leading Republicans and a living symbol of neoconservative power. Just three election cycles later, though he would never describe himself in such terms — at least not yet — he looms as a budding member of a different group entirely: the Resistance.

The day after Trump’s inauguration, in fact, Ridge walked along the Women’s March in D.C. as the event came to an end. He had been out running errands and stopped “not to participate, but to observe.”

Afterward, friends who are serious Trump partisans complained to him that the march — held in major cities across the nation — was “un-American … undemocratic … and just the most awful thing.”

Recounting these conversations, Ridge looks mystified. “It was a peaceful protest,” he says, “a pure expression of the First Amendment.”

The women, and men, carried signs. They chanted. Their solidarity, unity and love of country was something Ridge could feel just standing there.

He would have disagreed with them about many policy issues. But that didn’t matter. The march struck him as reflecting the beating heart of democracy. And this memory, of looking out over the crowd as the opposition party filed past him, seems to answer the question Ridge struggled with earlier — about this life-and-death moment, about whether there is any reason for his natural optimism. Because during that march in Washington, Ridge felt something he hadn’t expected: hope.

Where so many of Ridge’s Republican friends saw an America in turmoil, he saw America perhaps battered and scarred, but still functioning. “I was glad I went,” he says. “I actually found it … somewhat reassuring.”

Published in the April 2017 issue of Philadelphia magazine.