In Defense of Trigger Warnings

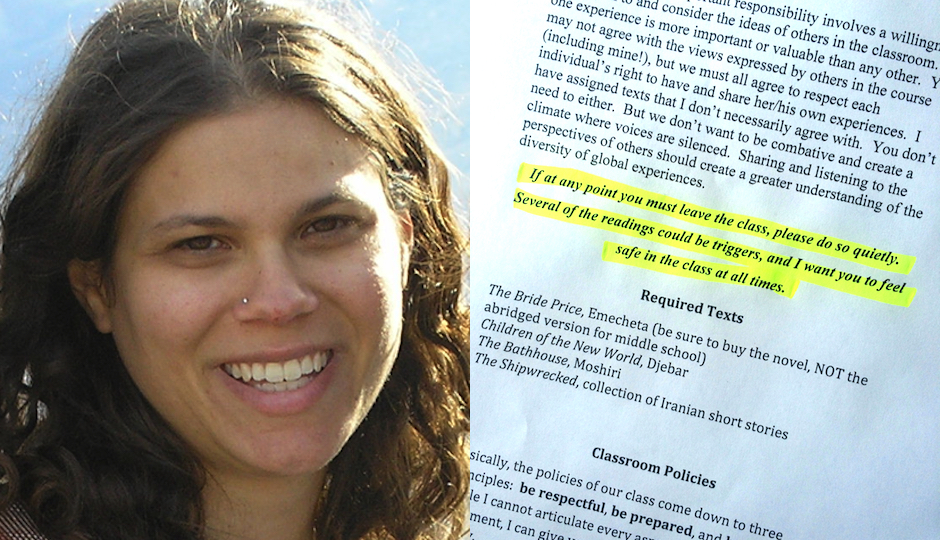

Left: Kutztown University director of Women’s and Gender Studies Colleen Lutz Clemens. Right: The trigger warning that appears on her new syllabus. (Highlighting added.)

Last week, the University of Chicago made national headlines when the school announced to incoming freshman that it does not support trigger warnings. (You can read the school’s letter to students here.) But Colleen Lutz Clemens, the director of women’s and gender studies at Kutztown University says that the University of Chicago got it all wrong. We reached out to her to learn more about the origin of trigger warnings, why she uses them, and why parents may be to blame for their existence.

Five years ago, no one was talking about trigger warnings. Where did all of this come from?

I put one on a syllabus back in 2009. I teach a class on women and violence in contemporary literature in which the women are the perpetrators of violence. I put a warning on the syllabus for that class. I didn’t even know what it was called. I basically put it there as an afterthought: Maybe I should just alert people that we’re reading all these violent things. It wasn’t something political. I just did it. And now, the fact that it’s 2016 and a university is putting out a statement like that, I just don’t get it. It astounds me. I’m amazed that this is something we keep talking about.

Why do you use trigger warnings?

My trigger warning tells the class that we’ll be focusing on texts that revolve around violence, and I want you to feel safe at all times. If you need to step out, you can. I’m asking them to read challenging material.

That doesn’t sound very unreasonable. So why are people so up in arms about trigger warnings?

A trigger is different than a discomfort. That’s what this letter is missing. A trigger is an actual symptom of something — usually PTSD related. I don’t know what these students are bringing in here.

So you’re saying that the University of Chicago just doesn’t understand trigger warnings?

That letter is almost smearing when it talks about safe spaces. Safe is exactly what I want my classroom to be. You know, the genesis of trigger warnings was in women and gender studies classes, and that’s probably part of why there’s outrage. These types of classes have always been controversial. Anything that has to do with women’s empowerment is a flashpoint. Honoring somebody’s identity and using language that honors that identity is not going to break America.

I don’t think the dean who wrote that letter knows what a trigger warning is.

A lot of people see trigger warnings as the latest way that we’re coddling our entitled youth.

It’s such an easy thing to say that we’re coddling America’s youth. Every generation says that. It’s an easy scapegoat.

We’re talking about one line on my four-page syllabus. This is such a minuscule part of what I do on a daily basis.

Your trigger warning says if you need to leave, leave. Has anyone ever left due to a conversation in class?

No. I’ve never had someone leave. The image is that kids are flooding out of classes the moment that they are being challenged. That’s just not what’s happening. It makes it safer for them to opt in to harder conversations. It creates a safe space.

I wish everyone on social media would be talking more about students who don’t have enough money for textbooks instead of talking about one line on a syllabus. A line that I put there so that students feel like they can talk.

OK, but where does it end? My house was once broken into when we were sleeping, and I’m still terrified. Car accidents. Alcoholic dad abuses mom. People go through all sorts of traumatic experiences. Do we need trigger warnings to cover every possible traumatic event?

Unfortunately, as you illustrate, trauma comes in all forms. I think a blanket statement is enough. Note that my warning implies that one should leave if one feels unsafe, not if one feels uncomfortable. I am not infantilizing my students; I think it is a basic right of a student to feel mentally and physically safe.

Shakespeare has a lot of violence in it. And there’s rape. Are you saying that my kids should be getting trigger warnings when they start reading this stuff in high school?

I taught high school for eight years. If I didn’t inform a class that we’re about to read something challenging, I would get a barrage of parent calls, complaining about the reading. Parents would call and complain about Lord of the Flies, saying it’s about Satanism. The high school no longer has on its shelves the young-adult novel Speak, because of the sex in it.

You don’t want us to coddle your children, but as soon as I give them something challenging, you’re saying it’s too challenging. If you’re so concerned about us coddling your kids, let us challenge them. If I hear one more time about Tuesdays with Morrie as assigned reading, I’m going to throw a book at someone.

Maybe I have to put a trigger warning on because these kids have been coddled and shielded by their parents. The same people screaming about trigger warnings are calling schools saying my kid can’t read about sexual violence. You can’t have it both ways.

Follow @VictorFiorillo on Twitter.