Sabrina Vourvoulias is an award-winning columnist with bylines at The Guardian US,AL DÍA News, Tor.com and Strange Horizons. Her novel, Ink, was named one of Latinidad’s Best Books of 2012. Follow her on Twitter @followthelede.

Want to Save a Historic Black Church in Philadelphia? You Have Until June 6th

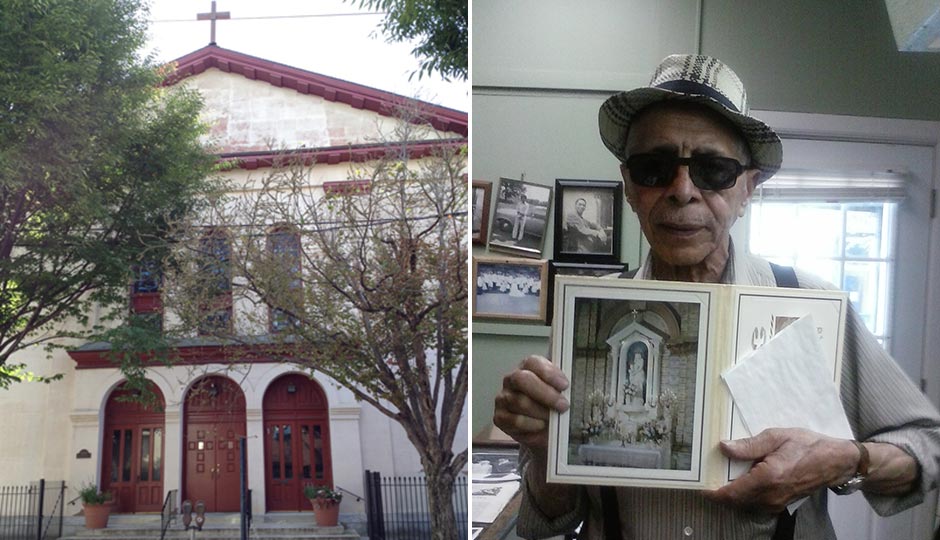

St. Peter Claver Church. Photo courtesy Arlene Edmonds. William Barney Richardson holds a Mass card for the Shrine of Our Lady of Victories inside the church. Photo | Sabrina Vourvoulias

In 1986, Cardinal John Krol suppressed it. In 2014, it was formally closed. And now, in 2016, the Archdiocese of Philadelphia is petitioning to remove the final bar to its sale — a deed restriction specifying that the real estate at 1212-1222 Lombard Street is held “in trust” for Black Catholics in Philadelphia — unless enough written objections to the petition are received by the Clerk of the Orphans’ Court Division of Philadelphia before a hearing to be held Monday, June 6, 2016, at 1:30 p.m. at Court Room 416 in City Hall.

The property in question is St. Peter Claver, the mother church for Black Catholics in the city since 1892, and a site of real symbolic and historical significance for more than just African Americans.

Although the register of Old St. Joseph’s shows that both free and enslaved Black people attended Mass in the Old City worship site opened in 1733, Masses there were segregated, with just a few Black Catholics believed to have been able to rent pews in the balcony gallery. The Black Catholic community which grew greatly during the 19th century thanks in part to an influx of Haitian emigres, commonly experienced having to sit in the balcony or back pews of churches during Mass, and having to wait for all white congregants to receive Communion before they could go to receive.

St. Peter Claver, dedicated in 1892 in the former Fourth Presbyterian Church on 12th and Lombard Streets, was the first and only Catholic church where Black Catholics could feel comfortable and at home. It had been purchased by members of Old St. Joseph’s, Old St. Mary’s and Holy Trinity churches who formed the St. Peter Claver Union and with the assistance of Philadelphia heiress (and later, saint) Katharine Drexel, they were able to purchase the property that first included a school for African Americans, and later the church and attendant property.

William Barney Richardson’s storefront sign calling for the reopening of St. Peter Claver Church. Photo | Sabrina Vourvoulias. The church’s historical marker. Photo courtesy of Arlene Edmonds.

The July 9, 1892, issue of the The Journal (a Black Catholic periodical published in Philadelphia) gives evidence of the community’s dedication to the church and what it signified in Philadelphia: in the obituary of P. Jerome Augustin — a Philadelphia-born son of a Haitian immigrant — he is proudly described as “one of the founders of the St. Peter Claver Church, to which he was strongly devoted.”

Arlene Edmonds, history buff, journalist and co-author the African American Catholic Youth Bible published by the National Black Catholic Congress, describes St. Peter Claver as part of the same “sacred ground” as other African American mother churches — Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, Wesley AME Zion Church — also located in South Philadelphia.

“I feel a special connection because I’ve always been interested in historical sites, particularly the Underground Railroad and the sites that were built from by those enslaved Africans who creatively masterminded their escapes,” Edmonds tells me. “Setting foot in St. Peter Claver one can feel it is part of that lineage. As a Catholic, so many of the earliest African connections to the faith have been overpowered by Western traditions after the faith was embraced by Europeans. Most American Catholic churches are centered around a Eurocentric interpretation of the faith.”

“Then you have a St. Peter Claver Church that was donated to the Black community for the purpose of evangelizing to the African Americans. They lived in Philadelphia during the antebellum era, were among those who escaped along the Underground Railroad, or who migrated here later from the south as well as the Caribbean and Latin America. This was their church before there was an Archdiocese of Philadelphia,” Edmonds adds. “It housed their history in photographs and artifacts. To have that taken from us is very sad. That is why many feel as I do, that others are trying to erase our history even those who say they share our faith. Now, rather than bring my daughters and grandchildren to St. Peter Claver to show them our history they will only hear about it, or possibly read about it, if that history is still preserved.”

The fight to preserve this site of Philadelphia African American history has been going on for a while and in disheartening stages that are hard to understand as anything other than abandonment by the Archdiocese.

“This is a unique church,” parishioner Grace Jones told Daily News staff writer Steven Marquez in a June 27, 1986, interview. “It used to be the nucleus of Black society in Philadelphia. If they close St. Peter Claver, they might as well close Independence Hall. It’s our heritage.”

At the time of the article, those protesting the suppression (which closes the parish to new parishioners and prevents the performance of sacraments like baptism, marriage or funerals at the church) accused Cardinal Krol of racism. Suppression guarantees a church cannot grow but simply dwindles as its existing parishioners age and die. Moreover, the measures whereby a diocese gauges the vitality of a parish (and therefore, what it will “invest” in the parish) are precisely those sacraments the suppression blocks — baptisms and weddings.

After the site was suppressed, the Archdiocese relocated its Office for Black Catholics to the site, and it became an evangelization center that conducted service programs and events from its South Philadelphia hub. But that was simply a sop. In 2014, the Archdiocese closed St. Peter Claver down entirely to prep it for sale in a rapidly gentrifying area of the city.

Now, in the third installment of the Archdiocese and St. Peter Claver saga, Black Catholics received notice — via an Office for Black Catholics email and via notifications published in selected church bulletins on May 22nd, May 29th and June 5th — of the impending hearing, and the Archdiocese’s petition to change the deed so that a sale of the properties can be effected:

“Please take notice that the Archdiocese of Philadelphia hereby gives notice to all Pastors of the Parishes in the Black Catholic Community, the Parishes of St. Thomas Aquinas, St. Charles Borromeo and St. John the Evangelist and to Deacon William Bradley as Director of the Office for Black Catholics, that a Petition for Cy Pres has been filed by the Archdiocese of Philadelphia related to the St. Peter Claver Parish and real property contained therein, and specifically for the removal of deed restrictions for real property located at 1212 – 1222 Lombard Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in the nature of a prohibition of sale and restriction of the use of the property using racial descriptions (…).”

But for William Barney Richardson, an African American Catholic baptized at St. Peter Claver and a longtime parishioner, the parishes where the Archdiocese placed those bulletin notices just goes to prove that “they don’t have an inkling of what is happening in the community.”

“That notice was an insult to Black Catholics,” Richardson tells me. The parishes selected to run the notice at one time were indeed 95 percent Black … but that time was “back in 1948-49.”

If they really wanted to reach Black Catholics, he says, they should have placed the notification in the bulletins of St. Francis de Sales, St. Ignatius, St. Benedict, St. Malachy, St. Paul, St. Thomas, St. Edmond, St. Charles, Our Mother of Sorrows, St. Athanasius, St. Raymond, St. Rose of Lima and St. Gabriel parishes — the parishes where Black Catholics are now.

“How can you have an Office for Black Catholics and then close down their mother church?” he says. “(That church) represents the history of the Black people in Philadelphia, and the dedication of the people — Jamaicans, West Indians, Portuguese —who fought to open that church and school.”

Richardson’s been fighting to keep St. Peter Claver open since it was first suppressed. He has a copy of the deed and says its charter gives ownership to the church’s congregation, not the Archdiocese. No decision, from suppression to sale, was supposed to have taken place without the congregation’s consent — a stricture no Archbishop, from Krol to Chaput, has bothered to adhere to, according to both Edmonds and Richardson.

“Instead of them wearing the sandals (of the Fisherman), they’re wearing sneakers,” Richardson says.

That “prohibition of sale and restriction of the use of the property using racial descriptions” quoted above that the Archdiocese is hoping to strike, is something St. Katharine Drexel built into many of the deeds and real estate transactions she helped secure for the marginalized communities her order, the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament, ministered to: African Americans and Native Americans, and even the Spanish-speaking Catholics of Philadelphia served by the mother church for Latinos in the city (La Milagrosa on Spring Garden Street, which the Archdiocese shuttered in 2013).

Will enough African Americans write to Clerk of Orphans Court opposing the Archdiocese’s intent to sell St. Peter Claver?

Richardson doesn’t know, but he’s a praying man. And he’s pretty sure both God and St. Katharine Drexel on his side on this one. After all, he says, that there is a church at all for him to be fighting for was “St. Katharine Drexel’s first miracle.” As for the Big Guy? Well, He hasn’t let St. Peter Claver church be lost yet.

“This moment is a wake-up call for Blacks,” Richardson says, “to know the value and the history of the only church (in the city) that has been a Black Catholic church from its very beginning.”

If you have objection to the granting of Archdiocese’s petition, you must state them in writing with the Clerk of the Orphans’ Court Division of Philadelphia on or before the 6th day of June, 2016 at 1:30 p.m. prevailing time, in Court Room 416, City Hall, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. If you do not file any objections, the Court may assume that there are no objections and may grant petition. For further information or a copy of the Petition, please contact: Nina B. Stryker, OBERMAYER REBMANN MAXWELL & HIPPEL LLP,One Penn Center Plaza, 19th Floor Philadelphia, PA 19103-1895. (215) 665-3057.