Sharswood Residents Experiencing PHA Deja Vu

The Norman Blumberg Apartments. Photo | PHA

Longtime residents of Sharswood, a part of the city located just north of Girard College in North Philadelphia, can tell you exactly when their neighborhood started heading south: 1969. That was the year the Philadelphia Housing Authority opened the Norman Blumberg Apartments, a 501-unit array of high-rise towers and low-rise garden apartments near its center. The crime that came with the tenants who moved into the project sent the neighborhood’s black middle class residents fleeing, starting a cycle of decay and abandonment.

The residents now living there have been meeting regularly of late with the Philadelphia Housing Authority to hasten the day when the project disappears. Last year, the PHA received a Choice Neighborhoods grant from the Federal government to plan for the Blumberg project’s replacement and study what should follow in its place.

One of those residents is a more recent arrival, a guy from Illinois named Adam Lang. Lang settled in Sharswood almost a decade ago with an eye on sticking around the neighborhood. He soon got involved in both Republican politics and neighborhood issues, working with neighbors to help bring a supermarket (the since-closed Bottom Dollar) to the area and taking an active role in the neighborhood civic association, which has devoted much time and energy toward restoring the neighborhood to the condition it was in before the PHA opened the Blumberg project.

His neighbors have, as a result, accepted him as part of the community. He hosts movie nights and other neighborhood events on the empty lots next door to his house, lots that he purchased from the PHA with the aim of making them a side yard for his home.

Imagine his surprise, then, when he got a letter from the PHA on January 15th saying the agency might want to take them back sometime this fall.

•

SOME 1,200 OF his neighbors were sent the same letter on the same day. Some of the letters probably never got to their intended recipients, as the addresses they were sent to are now empty lots like the three Lang owns. Some may have gone to property owners long since deceased or otherwise unreachable. But others went to actual residents like Lang, and they were no happier to get them than he was.

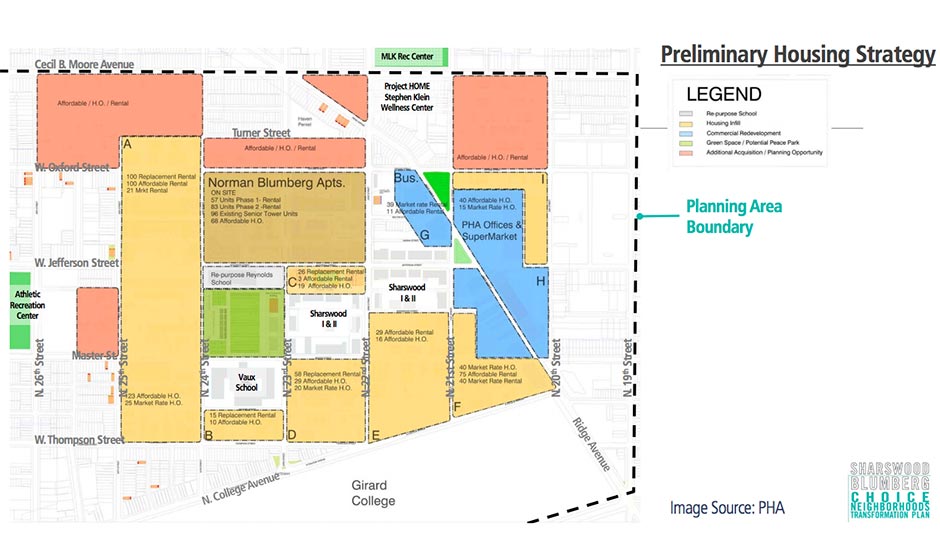

The reason for the letters? The PHA now wants to build a massive new development that would replace the Blumberg Apartments, which all agree are a major obstacle to getting rid of blight in the area. Two of the three towers (one will remain for senior housing) and all 13 of the low-rise units on the site will be demolished and their units dispersed across parts of seven adjacent blocks in addition to the two the project occupies (see map below). In addition to the 339 replacement units and 96 in the senior housing tower that will remain standing, the PHA plans to build an additional 723 units — 318 rental units and 405 homes for sale — on nine tracts of land covering roughly 10 blocks to the project’s south, east and west.

Preliminary Housing Strategy. Photo | PHA

The surprise wasn’t that PHA had plans to replace Blumberg; the agency has been meeting regularly with Sharswood residents and the neighborhood’s civic group, the Brewerytown Sharswood Community Civic Association (BSCCA), on planning for the new development for the last year. What seemed to catch residents off guard was the amount of land the agency wants to redevelop, the number of existing homeowners it plans to displace to do so, and the suddenness with which it has moved to take the land.

“We had a two-year planning timeline as part of the Choice Neighborhoods grant” the city received for this redevelopment plan, “but the city is moving ahead of the Choice timeline,” said Lang. “We weren’t expecting PHA to go after the land so soon.”

•

COMPLICATING MATTERS, THE city may not have an accurate count of how many occupied properties it has moved to take. “The vice president at PHA says that a little more than 70 properties are currently inhabited,” Lang said, “but the problem is that the figure is based on the city’s data. On my block alone, there are at least half a dozen structures the city lists as vacant properties that I know people live in, and there may be a lot more people living in houses they consider vacant.”

(One of them, it turns out, is Lang himself; at the BSCCA’s February monthly meeting, which featured a presentation and a question-and-answer session with PHA Senior Vice President for Policy and Planning Eric Solivar, Lang stated that his home was one of the properties the PHA had wrongly classified as vacant.)

The neighbors who showed up at a mid-January meeting that the PHA invited the targeted property owners to attend were no happier than Lang was about this development. One, Lang said, “scoffed at the notion the PHA was going to fix the neighborhood when they were the ones who destroyed it.” Another called the agency “the worst landlord in the city,” and another remarked that “now that the neighborhood’s finally getting some investment, the government wants to turn around and take it all away.” Lang also noted that the occupied properties, which now pay taxes to the city, would go off the rolls under PHA ownership.

Some of the residents who turned out to hear Solivar explain what the agency was doing at the February BSCCA meeting voiced similar skepticism. One commented on the high ratio of affordable to market-rate units in the mix. Counting the 339 replacement units and the 96 in the senior tower, 958 of the 1,158 units the PHA wants to build or retain will be “affordable,” which the agency defines as within reach of someone making 85 percent of the area’s median income — “if you make $50,000 a year, you should be able to afford these homes,” Solivar said. That didn’t go down well with BSCCA president Warren McMichael, who said, “We would like some market-rate housing in this community. We don’t want it all low-income.”

Lang asked how the authority determined which properties were vacant and which were occupied. Solivar confessed that the agency did drive-by assessments. It had to, he said: “At the time we did the drive-by, we did not have the legal right to even knock on your door. So we went by and asked [ourselves] whether a building looked occupied or not, and if it looked occupied, whether it was owner-occupied, renter-occupied, squatter-occupied or illegally occupied. As we get responses to our letters, our numbers will be revised.”

It may well be that the PHA will not need all the properties it has expressed interest in to build the homes it wants to build. Solivar said in a post-meeting interview that there will be a procedure by which owners who do not want their property taken may ask to have it removed from the list if possible. (It may not be possible, however, if the property allows the agency to assemble a contiguous parcel for development.)

Solivar explained that the agency plans to start moving residents out of the Blumberg project in July and that it hopes to complete land acquisition in October or November. “We anticipate, and I say this with a lot of asterisks, bringing down the towers this fall,” he said. “We will revise the timeline as paperwork comes back and we see what the responses are” to the letters the PHA sent out.

WHAT ACCOUNTS FOR the accelerated timeline? Some of it may have to do with the sheer ambitiousness of the project. The housing is just one part of a comprehensive revitalization strategy that includes a revived business corridor along Ridge Avenue anchored by a supermarket and a new headquarters for the PHA, improved education and job training resources for residents, and promotion of entrepreneurship in the community.

In an op-ed last November, PHA President and CEO Kelvin Jeremiah noted that the agency already had the funding in hand to proceed with the first phase of the redevelopment project, which involves demolishing the two towers and building 57 new housing units on empty land on the Blumberg site. “PHA has aligned its ideas, policy and finances to be able to achieve its goal of transforming a targeted community,” he wrote. “PHA is making this investment in Blumberg/Sharswood now because, for too long, families in the community were told to wait. The wait is over.”

Not everyone who attended the meeting was convinced that the PHA could actually pull all of this off. One resident noted that PHA officials had told them that the agency chose Sharswood as the site of the Choice Neighborhood development plan because the agency “did Sharswood wrong.” (Solivar agreed that was the case and added that inadequate funds for maintenance didn’t help matters any.) “But what’s to say that 20 years from now, the same thing won’t happen with what the PHA is developing now?”

Solivar did not identify any funding in hand to proceed with anything beyond that first phase, which also requires construction of the replacement units on other lots. That led Lang to question the rush to acquire so much land now. “PHA estimates that this will be a $500 million investment, so the money must be coming from somewhere,” Lang said.

A PHA spokesperson characterized the community as being in “desperate need for revitalization,” hence the urgency to acquire land for the project. Lang’s worry is that if the funding is not in place, the land could ultimately sit vacant for years — the opposite of revitalization.

Follow @MarketStEl on Twitter.