City Council Holds Marathon Hearing on Youth Gun Violence

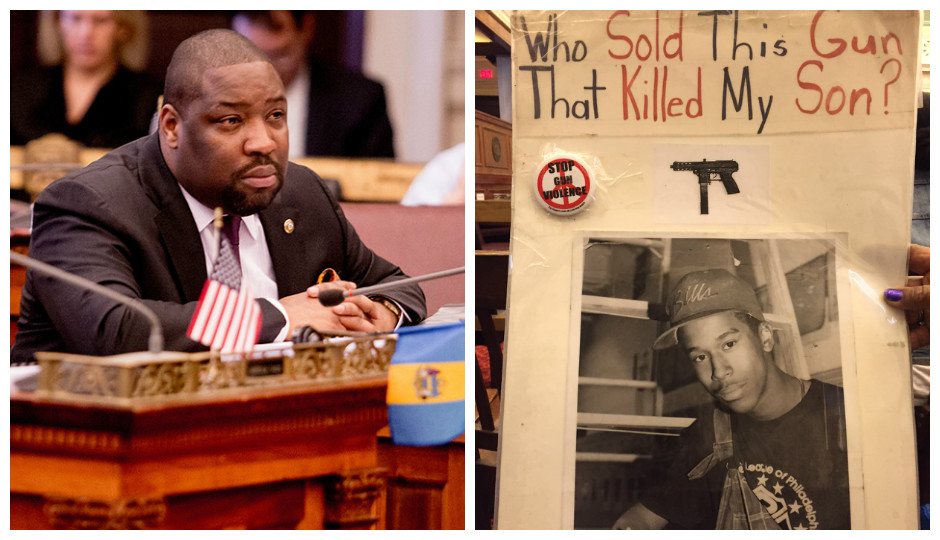

Kenyatta Johnson (Jeff Fusco)/Poster of Terence Ryans (David Gambacorta)

Cherie Ryans sat quietly in the back of City Council chambers this morning, propping up a poster with a black-and-white photo of her son.

Terence Ryans is frozen in time in the picture — 18, skinny, a Bills cap on his head, a hint of a mustache lurking above a faint smile. A smaller image of a Tec-9 semiautomatic hovers above Terence’s photo, along with eight words that cry out in black and red ink: Who Sold This Gun That Killed My Son?

In a soft voice, Ryans, 66, explained that her son was shot to death — along with his best friend, Darren Norwood — during Labor Day weekend in 1990. Terence was a student at Cheyney University; he lost his life because he was at the wrong place at the wrong time. (It is, indeed, a gut-wrenching story.)

She and other members of one of the world’s saddest clubs — mothers who have buried their children — attended a marathon hearing on youth gun violence in Philadelphia that was held by Council’s Committee on Public Safety.

Thirty people were scheduled to testify. The witness list ran the gamut from doctors to politicians to members of the clergy and grieving mothers.

The goal, according to City Councilman Kenyatta Johnson, was to hear from all of the different parties who are impacted, in one way or another, by youth gun violence, and begin stitching together a comprehensive strategy to combat a problem that has become a full-blown epidemic in the city.

“Youth gun violence, here in the city of Philadelphia, needs to be our number one priority,” said Johnson, who chairs the Committee on Public Safety.

The numbers certainly paint a desperate picture. Assistant U.S. Attorney Robert Reed testified that more than 4,700 people have been murdered in Philadelphia since 2001. More than 22,000 people have been shot in the city during that same period of time.

Joel Fein, the director of the Violence Prevention Initiative at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said CHOP’s emergency room doctors treated more than 400 juvenile gunshot victims in 2015. Some were as young as 2 years old.

Kathleen Reeves, the senior associate dean for Health Equity, Diversity and Inclusion at Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University, testified that the overall cost of gun violence in the U.S. in 2012 was $229 billion, about $90 million more than the budget for the U.S. Department of Education, Daily News columnist Helen Ubinas tweeted.

Beyond the grim data, there was a staggering, almost overwhelming amount of information shared about all of the various ways different city agencies and community organizations attempt to prevent young people from picking up guns and causing irrevocable harm to their lives and the lives of others.

The hearing at times felt unwieldy; as Al Dia reporter Max Marin noted, the conversation topics included children and communities suffering from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder; recidivism; a general lack of education and employment opportunities; police policies; a lack of awareness around mental health problems; parenting philosophies; re-entry programs for ex-offenders and many other subjects.

(There was also a lengthy disagreement between First Assistant District Attorney George Mosee and Karyn Lynch, chief student support officer for the School District of Philadelphia, over the truancy rate in public schools.)

Everyone in the room agreed that more can be done to put young people on better paths, to help them address their anxiety and anger in ways that don’t involve violence. But that was to be expected; who was going to walk into City Hall and argue that things are just A-OK in the city that saw 10 people shot in just a single day last week?

The bigger question is where things go from here. Kenyatta Johnson and City Councilman Curtis Jones Jr., went out of their way to describe how personal the issue of youth gun violence is to them; Johnson recalled a cousin and friends being murdered when he was younger, while Jones recounted being a teenager and seeing a female friend get shot.

Jones pushed the witnesses, including Police Commissioner Richard Ross and Kamilah Jackson, the deputy chief medical officer for child and adolescent services at the Department of Behavior Health, to identify programs that are working, but could do better with additional funding.

“We want to put our money where our mouth is,” Jones said.

Johnson said upcoming budget hearings will be an opportunity to evaluate how well the city is supporting anti-violence efforts.

Cherie Ryans said she felt optimistic after listening to the first half of witnesses testify in the morning. This could be more than just a bunch of politicians saying the right things about a serious issue.

“We’re going to stay on these people. They have an obligation, because it’s their jobs,” she said. “But we have an obligation because we’re mothers who have lost children. We don’t want another mother to deal with what we deal with every day of our lives.”

Follow @dgambacorta on Twitter.