10 Big Ideas to Solve Philly’s Looming Jobs Crisis

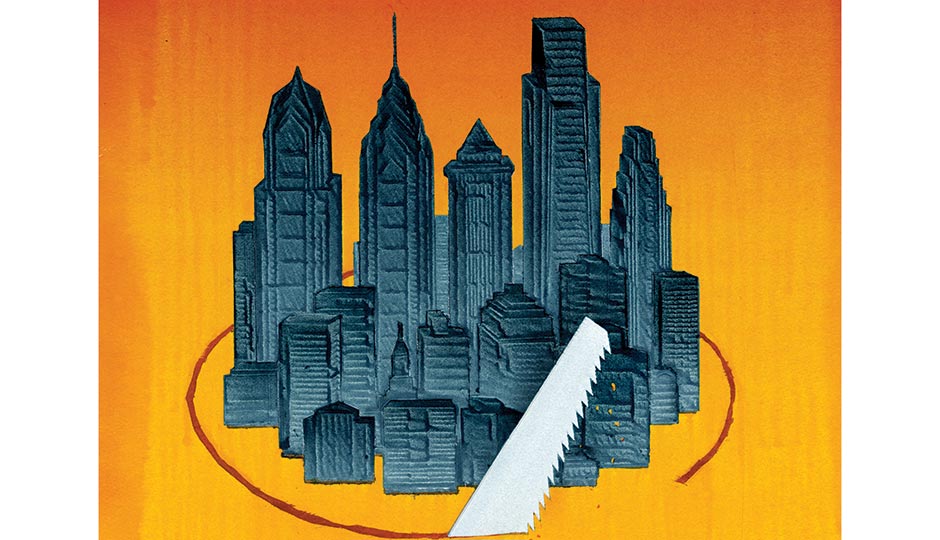

Illustration by Alex Nabaum

There is in this city a coming-of-age narrative — the Story of Philadelphia’s Rise — and unless you’ve been living under a rock, you know this story well. It’s been told and retold by everyone from realtors to corporate recruiters to this magazine to the New York Times, and the basic plot goes like this: Once upon a time, Philly sucked. Laid low by the death of manufacturing and urban flight after WWII, the city by the 1970s was a pretty dismal place — a ghost town, all empty storefronts and streets. And then, a shift. Ed Rendell kicked us out of near-bankruptcy. The economy started growing; so did the city’s appeal. John Street focused on neighborhood improvement; the Center City District cleaned the place up. Now? It’s a whole new Philly. Center City booms, as does University City. We’re green, clean, walkable and bikeable, with a thriving hospitality industry and vivacious neighborhoods. There’s Comcast, the Navy Yard, the emerging start-up scene, all those millennials flooding the place. But you already know all of this.

There’s another story, too, though it’s not as well known. It’s certainly not as cheery as the first. It’s about economic growth, or the lack thereof, and it goes like this: For years — decades, actually — we’ve grown new jobs too slowly. Other major cities are attracting more companies, more talent, more money, at much faster rates. And this problem, roiling against the backdrop of revival, is more than a dark cloud in an otherwise sunny landscape: It’s a direct threat to all of Philly’s progress.

Truth is, Philly’s remarkable resurgence is less a product of innovative long-term planning and more the result of, well … happy accident. Over the past decade, especially, we’ve benefited immensely from a renewed national interest in cities (especially among millennials and boomers), a handful of major players hitting their stride (thanks, meds, eds, Comcast), and an unexpected population boom (more births than deaths, those enthusiastic millennials, and a steady flow of immigrants).

And sure, we have to give credit to the leaders who knew how to make the most of our upswing. But the circumstances of our growth still raise the question: What happens to our resurgence when Philly’s population boom slows? According to census numbers, it already has. More people are moving out of Philly than are moving in, and we were approaching “peak millennial” back in 2015, at least according to real estate research firm JLL Research. The forecast for immigrants isn’t looking super-sunny these days, either. As strong as they are, meds, eds and Comcast can’t carry a whole city. Are we poised to keep up our momentum? Are we ready for the future?

The simple answer is no. And if we don’t change that now — if we don’t treat our slow growth like the crisis it actually is — we could find ourselves headed back to the bad old days, back to the struggle. Back to decline.

I know all of this crisis talk sounds improbable. Hyperbolic. After all, nobody’s talking about shutting down libraries or declaring bankruptcy. In fact, part of the problem of this jobs problem — aside from its inherent unsexiness — is that “slow growth” is still growth. And everything looks pretty okay. Isn’t that a new park right there? Isn’t my home value climbing? Can’t you count a dozen or more cranes around the city at this very moment?

All the progress we see is real, but it’s just part of the truth. The other part is that some 39 percent of working Philadelphians are currently commuting out of the city for their jobs. And according to a 2014 Pew survey, millennials — you know, that vaunted group that makes up more than a quarter of Philly residents right now — cite job opportunities as the number one reason they’d pack up and leave the city. (Schools are second.) “A promising but fragile boom,” Pew called the Philly millennial phenomenon. The suburbs, meantime, are ready to answer the call: Construction there — office, residential, mixed-use — is booming, and developers are targeting a younger, more citified demographic.

Companies, too, feel the pull of other towns and cities, weighing everything from lower taxes to closer proximity to various centers of industry not in Philly. “Center City is losing its position as a corporate metropolis,” lamented the Inky a few years back, pointing to the fact that even as jobs in some sectors grew, headquarters — those magnets for outside money and business opportunities — were leaving, including Cigna, Sunoco and Destination Maternity (and, since then, Monetate, with Equus Capital Partners to follow when its lease expires next year). And it’s not just the headquarters — a handful of factories have also packed up and left town in recent years.

Also true: The 25 biggest cities in America added jobs at the average rate of 2.8 percent a year between 2010 and 2015. Philly lagged behind at 1.1 percent. And while the most recent Pew report (released in April) notes that Philly job growth outpaced the nation’s in 2016 for the first time since the Great Recession, it’s the initial city-to-city comparison that was a focal point of the Center City District’s latest report — tellingly titled “An Incomplete Revival.” And it’s that comparison that’s got CCD president Paul Levy all riled up. “Look at all the cities growing faster than us,” he tells me, pointing emphatically to a bar chart that shows Philly dead last on a list that includes New York, Chicago and L.A., yes, but also Jacksonville, Baltimore and Detroit. “It’s embarrassing.”

His point isn’t really that he’s embarrassed, but that comparison actually matters. In a global world, we’re competing with other cities — for talent, for businesses, for money. And on this front, we’re not winning.

If the notion of fighting for global dominance sounds uncomfortably Trumpian, consider one way slow economic growth hits closer to home: As more of the middle class leaves the city, the CCD notes, the percentage of Philadelphians who live in poverty rises — a larger portion of a smaller whole. And right now, Philadelphia claims the highest poverty rate of America’s 10 largest cities, with one quarter of us living below the poverty line. Aside from being morally unacceptable, our poverty problem cripples our schools, which drives out still more middle-class families (and their tax dollars), which cripples the city’s budget, which cripples the city’s ability to serve its constituents and plan long-term. And all of this, of course, cripples our shot at growing jobs. You see the problem here.

And yet: This is less a doom-and-gloom story than it is a call to action. This spring, I talked to stakeholders, politicos, thought leaders and business owners in this city about growing jobs here. And while few of them agree about much of anything, two sentiments held true, almost to a person. One is that Philly is, at this moment, better than it’s ever been, with more potential for growth than ever. The second: We must mobilize that potential now — and we must do it faster and with more intent.

“I think what we need now is a fresh approach,” says Councilman Allan Domb, who emphasizes the necessity of long-term planning. “We need to look at every process, everything we do, and say: If we didn’t do it this way, if we started fresh today, how would we do it now? Otherwise, everything is just a Band-Aid. And 60 years of Band-Aids doesn’t work.”

In that spirit, and in an effort to not let a crisis go to waste, we consider 10 fresh approaches — 10 ideas about fostering job growth coming from a range of viewpoints and agendas. Some are widely supported, some are not; none are obvious silver bullets. But all aim to tackle in a real way what’s been broken in our city for a long time now … and get us started fixing it while we still can.

Illustration by Alex Nabaum

Idea One: Treat the jobs issue like the crisis it is.

One of the popular complaints from the non-government sector is that Philly hasn’t had a sense of urgency when it comes to economic growth. “It’s not a crisis of survival like the crisis of the early ’90s,” Drexel president and Chamber of Commerce chairman John Fry told that group last fall. Instead, he said, it’s a “crisis of opportunity,” propelled in part by “complacency, perhaps bred from recent successes.”

As we’ve said, it’s become apparent there’s no time to rest on the laurels of, say, a glut of millennials (promising but fragile, remember?), a revitalized Center City, or the immense strength of meds and eds (vital, but it’s worth noting that they don’t pay taxes). “No matter how well we’ve done, we’ve got more work to do, and so does the rest of the region,” says city commerce director Harold Epps. “We’re being outpaced by the Sun Belt and right-to-work states, and we are going to lose Congressional seats. We all have to find new ways to stay relevant and competitive.”

A great first step: a concerted campaign from the Kenney administration that highlights the urgent need for new jobs. Per his campaign promise, the Mayor spent his first year focused on pre-K and Rebuild (whose mission is revitalizing parks, rec centers and libraries) and the soda tax to fund them. He showed he can be pointed, dogged and intentional. According to Commerce Department communications manager Lauren Cox, that department is, at this moment, working on a larger strategic plan. But 18 months in, we’re in dire need of a message from the top — We have a problem here — followed by a plan of attack that mobilizes us in a common cause. Nothing brings people together or spurs innovation faster than a crisis, so let’s get busy ringing some alarm bells.

Idea Two: Be friendlier to business (on a micro level).

“Maybe this is just perception,” restaurateur Stephen Starr says, “but I don’t think there’s been leadership that makes businesses feel warm-and-fuzzy and welcome since Rendell left.” (Starr currently runs 20 restaurants in Philly, employing 2,177 people.) Back then, he says, there was a sense that business was a good thing. “Maybe that was just good PR. But I think now there’s an underlying sentiment among the bureaucracy that business is bad. Greedy. Only looking out for itself. It doesn’t seem like a good attitude to have if you want to grow business. It’s like getting married thinking of all the bad stuff your spouse might do instead of the good.”

It’s not just perception, says David L. Cohen, senior executive VP of Comcast, longtime Democratic honcho, and co-chair of the Chamber of Commerce’s “Roadmap to Growth” plan for the city. “Over the last four to eight years, Philadelphia has developed a reputation as one of the most anti-business cities in America,” he says. “I travel the country for Comcast and my nonprofit work. I’m not exaggerating when I say I get asked all the time: What’s going on in Philadelphia?”

What’s going on is that a series of small inefficiencies and larger obstacles paints a picture of a city that if not hostile to businesses isn’t so hospitable, either. Consider David Bookspan, the founder of tech accelerator Dreamit who just launched the adtech start-up Curren-C, which he and partner Will Luttrell headquartered in Philly, flouting advice from their lawyers and accountants. “They said, ‘Are you sure you want to be in Philly?’” Bookspan says with a laugh.

“Will and I are both committed to Philly for a number of reasons. We think it’s a great city that has lots of advantages — location, quality of life and talent pool, to name a few, plus a lower cost of living.” Mayors Kenney and Nutter and a handful of other city players have also been “extremely committed” to helping the start-up community, he adds.

But, Bookspan says, on the con list was Philadelphia’s high city wage tax. (We’ll get there in a minute.) He also recounts the comedy of errors that was the day he tried to follow state and city new business registration protocol: dead ends on email, a 35-minute phone hold time followed by a disconnection, a Philly “help line” where every option was broken. Not exactly a welcome mat for entrepreneurs — especially considering the pair had an easy time with the same chores in other states.

Bookspan isn’t alone in his call for more updated processes to ease doing business — other people called out everything from incomprehensible tax codes (“You need a Philadelphia lawyer to get through it all!” says one business leader) to a lack of technology. In his February speech to the Chamber of Commerce, Mayor Kenney noted improvements to L&I in particular, but it’s still a long haul toward modern-day efficiency. It’s 2017. Let’s get at it.

Idea Three: Be friendlier to business (on a macro level).

When it comes to that warm, fuzzy feeling Starr talks about (well, the lack of it), one of the biggest culprits has been an active city government — one that has, according to Cohen, unwittingly created an “anti-competitive stance.”

An anti-competitive stance? I ask for specific examples, and Cohen spends the next several minutes rattling off eight years’ worth of new taxes and bills — a list I’m seriously condensing here — that include a bumped-up sales tax, a parking tax and the new soda tax, plus a whole slew of city ordinances regarding, for example, mandatory paid sick leave, “ban the box” rules for ex-offenders on job applications, requirements for city-hired contractors to disclose the percentage of female officers and managers, gender-neutral bathrooms, and wage history prohibition. For starters.

“When someone says, ‘Look, we’re not anti-business, we’re pro-employee,’ what they don’t understand is that as employers, we’re pro-employee, too,” Cohen says. Nobody, he adds, is coming down on the side of, say, discrimination. “But if the net effect of all this is to cost 20,000 jobs, for example, how are you pro-employee?”

It’s a valid if ideologically tricky point to make in a city that likes its progressive values — a tension Cohen is keenly aware of (as are, I might add, many others. Starr says: “God, I cringe at sounding like a Republican. I’m a lifelong Democrat who vigorously supports Democratic ideals. But I think there’s got to be a balance between protecting people and protecting small business.”).

Taken one by one, Cohen offers, “These are all reasonable things. But there have been 20 actions by the city government in the last eight years, independent of state and federal regulations, and no matter how well-intentioned it is from a progressive, Democratic perspective, cumulatively it sends the message that this is not a city open for business.”

It does seem that people are coming on board with this line of thinking. In March, Council President Darrell Clarke created a Special Committee on Regulatory Review and Reform — co-chaired by Councilman Derek Green, commerce director Epps, and Chamber of Commerce president Rob Wonderling — to review all regulations on the books and recommend fixing (or killing) the overcomplicated or outdated.

Idea Four: Fix the freaking taxes already.

Eyeball-glazing as any talk of tax reform may be, there’s no bigger plan in place right now than the one aiming to revise a tax structure that gives Philadelphians good reason to live and work anywhere but Philadelphia. (That reason is cash in their pockets.)

There’s a long, convoluted history here, but the CliffsNotes version goes like this: As far back as 2003, a city tax commission concluded what many people had suspected for a while: Our city relied too much on taxing what could move (jobs and people) and not enough on what can’t (property and land). This hurt Philly from both a revenue and a job-growth perspective. Philadelphia’s wage tax — levied on people who live or work in the city — is 3.9 percent for residents and 3.47 percent for non-residents, or almost four times the regional median, according to the CCD. The upshot is that people who move out of the city get pay raises. Conversely, if a city company wants to recruit an outsider for a job, the employee or the company eats that 3.9 percent.

On the flip side, only 19 percent of the city’s budget comes from property taxes — a puny slice compared to D.C.’s 36 percent and New York’s 43 percent. Sixty-five percent of our budget comes from wage and business taxes. And speaking of business taxes: Philly’s business income and receipts tax (BIRT) raises the cost of doing business here 20 to 30 percent over suburban costs, according to the Philadelphia Jobs Growth Coalition.

About that coalition: It’s a mix of labor leaders and business and civic groups that the CCD’s Levy and Brandywine Realty Trust CEO Jerry Sweeney corralled in 2011 with the goal of, yes, growing jobs by flipping the city’s tax structure. The idea is to increase commercial property taxes by 15 percent (from 1.39 to 1.61 percent, more in line with other cities), then lower the wage and BIRT taxes in return. “What this is,” Levy says, “is businesses in the city saying we’re willing to pay more on property to finance wage and business tax reduction.”

In addition to the big-picture benefits the coalition touts — more incentive for businesses (and workers) to stay, a wider revenue base for the city — projections over 10 years include 79,000 new jobs created (from high-wage positions to janitorial jobs and beyond) and an extra $362 million for the Philly school district. And while the city’s been lowering the wage tax slowly over the past 20 years, more aggressive slashing would provide a noticeable pay raise for every worker in the city, Levy says — without costing the city a cent.

Given all of this (plus years of lobbying), it’s not surprising that the so-called Levy-Sweeney plan has won support, including from the Mayor and a handful of state legislators. The last bit is vital, because for the city to raise commercial property rates above residential rates, Harrisburg has to agree to change the state constitution — an arduous haul, to say the least. But the amendment passed in the House and Senate last summer; now it’s up for a second vote in both legislative bodies. Then, should it pass, it’s on to a Commonwealth-wide referendum. Only after it wins there would Council have the option of raising commercial taxes (and then, only if the raise is matched by a reduction of the other taxes, and only if they stay within 15 percent of the residential tax rate).

Still, Sweeney says, just the option of raising commercial rates is a tool for growth. Not everyone agrees. Council president Clarke is for amending property taxes but isn’t on board with the amendment’s requirements to lower wage and business taxes or with the 15 percent cap for commercial taxes. The Chamber of Commerce — trying to work through its own five-year tax reform plan with Kenney and Council before the vote — worries that taking local tax reform to the state stage, where mandatory schedules will be set, creates bad precedent.

Both sets of concerns have merit, but after decades of dallying and debate and small tax cuts and still-straggling growth, a substantive, data-driven plan with supporters ranging from the African-American Chamber of Commerce to Local 98 is well worth a shot.

Idea Five: Zero in on transit and infrastructure.

As big, bold plans go, this may feel a smidge … pedestrian, but between the federal windfall that we miiiiight get for infrastructure, the state money already pledged to it, and a true, desperate need for updated roads and bridges, investing in infrastructure is a no-brainer, particularly because — as Epps notes — the significant amount of work that needs to be done is a pretty good match for our labor-heavy workforce, and every investment yields a boost in jobs and in the competitiveness (and livability) of the region.

There are some projects in the works, including the massive $225 million plan to cap I-95, the airport rehab plan, and the eventual transformation of 30th Street Station, but leaders need to keep big and small projects moving along.

Illustration by Alex Nabaum

Idea Six: Have public-private partnerships focus on schools.

When you talk about growing the economy, business-and-government collaboration comes up a lot. But nowhere is there more potential for businesses to make an impact on Philly’s future than in our schools.

Approaching our flailing public schools from a purely economic standpoint might feel socially tone-deaf, but for the sake of brevity, let’s stick to the jobs lens. Businesses have two major reasons to get heavily involved in a school turnaround. The first is talent attraction and retention: If skilled, educated workers don’t want to be here or stay here because they don’t want to send their kids to school here, why would businesses stay here? The second compelling argument involves the longtime complaint in the business world about Philly’s undertrained, undereducated workforce. On one hand, we have a clutch of world-class universities pumping educated workers right onto our stoop. On the other hand, we have a high-school graduation rate of 65 percent (compared to the state’s 84.8 percent) and a city in which nearly half the adults lack the education and work-ready skills for what the city’s Office of Adult Education calls “family-sustaining jobs.”

The new pre-K program is a step in the right direction, but in the meantime, we have kids, points out Bob Moul, CEO of Cloudamize and former board chair of Philly Startup Leaders, who aren’t being taught technology as part of their core curriculum. “It’s 2017!” he says. “Even mechanics today are hooking cars up to computers. And there are somewhere between half a million to a million unfilled IT jobs in this country.” In fact, the Economy League recently reported that a quarter of the 100,000 new jobs created in the Philly area since the early 2000s are tech jobs, but employers can’t find candidates with the right skills. Meantime, Moul adds, even vocational schools aren’t focusing on tech enough. “We’re putting them on [career] tracks at SEPTA and PECO, but how about we create more internships in the tech and business community, putting them on paths to those jobs? To me, it’s a win-win.” And this doesn’t just hold true for tech.

Many examples of such partnerships already exist throughout the city, Cohen points out. They can and should be expanded and scaled up with the business community at the helm, whether we’re talking adopt-a-school programs or company-sponsored mentorships or even deeper investments like the oft-touted example of North Philly’s Cristo Rey, based on a model out of Chicago. At Cristo Rey, high-school kids work five days a month at corporate internships with partner companies (Beneficial, Glaxo, Cozen O’Connor, Wawa and the Philly Zoo, to name a few). The students get paid $7,500 for their work (it goes toward school tuition) and gain on-the-job education. The first two graduating classes, in 2016 and 2017, have had a 100 percent college acceptance rate. Businesses, meantime, get reliable, affordable help and the chance to put some money where their mouths are in terms of training the workforce. Win-win-win.

Idea Seven: Talk to each other.

Speaking of workforce development, there’s an interesting project afoot right now: a partnership between the Commerce Department and the Managing Director’s Office that aims at growing a stronger population of trained workers. What’s compelling here isn’t just the focus, but the scope of what they’re trying to do. Come fall, the workforce development committee (led by Epps and managing director Mike DiBerardinis, with involvement from nonprofits, organized labor, philanthropy, government and many more entities) will unveil a citywide strategy that identifies the manpower needs of our private and public sectors — who needs workers that they can’t easily find? — and aims to train a workforce with those specific skill sets.

“We are trying to be very intentional,” says Maari Porter, director of policy and strategic initiatives in the Managing Director’s Office. “We want to train into open positions, train people into a job, really embrace partnerships with employers.” They found inspiration, she says, in a similar initiative in New York for which businesses, organized labor, philanthropy, government, educational institutions and service providers sat together over five months of discussions that produced a strategic partnership between employers, trainers and the city.

If anything, a program like this shows the immense power the city has to bring together different perspectives and new collaborations — and not just as it relates to workforce training, but as it could relate to any of the city’s challenges. “Let me tell you, I see more and more business people who want to get involved,” Domb says. “They want to take on a role. They approach me. They know that without a healthy city, you have no business.”

Idea Eight: Sell, sell, sell.

The highlight reel of Philly attributes puts other cities, even faster-growing cities, to shame. Now we just need to sell the hell out of it all.

Think about how successfully Philly has marketed itself to visitors and tourists, says John Grady, president of the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation. (True: 41 million people visited the city in 2015 alone.) “More and more people from outside the region are hearing good things about Philadelphia, and that’s the result of hard work and a conscious investment of resources in developing a brand for Philly as a place to come and visit,” he says. “I think we need to do the same thing for jobs.”

So what’s stopping us from promoting our innovation, diversity and talent the same way Visit Philadelphia has promoted restaurants and neighborhoods? Really not much more than a branding effort. And that branding should be focused, for one thing, on talent. “Employers follow talent,” Grady says. “The more talent you have, the more you can recruit. And more students in the region are staying here because of our value proposition — so we’ve got quality of place and quality of workforce.”

According to Epps, the Commerce Department is collaborating with Visit Philly, the Philadelphia Airport, the Chamber of Commerce and the Convention & Visitors Bureau, among others, to create more consistent messaging. But why not go bigger? Let’s loop in the big recruiters, the state government, Citizen Diplomacy International, the universities, the tech community, the big regional players. Just imagine the selling might of all of those powerhouses on board, together, on message.

Idea Nine: Leverage those eds and meds.

When it comes to building jobs and companies, says David Bookspan, “You need to be able to leverage the natural resources of that community.” And Philly? “Well, this is where health care happens.” Dreamit, Bookspan says, launches 20 or 30 healthcare companies a year — but he posits that Philly as a city could see more like 100 new health-care start-ups a year, with the vision and the cash. The city already has the facilities, talent and institutions, and that makes Philly a right fit for health-care-focused firms-to-be, he says — not to mention the capacity and the proven methodology. “In my view, we’re just underperforming in the investment,” he says. “And for that, we need major business leaders and corporations to make it happen.”

It’s this type of ambitious, synergistic vision — not totally rare, but not nearly as predominant as you’d think in a city that has such enormous “natural resources” — that could launch the next Comcast, or Aramark, or Dreamit. As Cohen points out, it’s not easy to lure big companies to a new market. We need to grow them here.

Idea Ten: Steal what works.

In Nashville, the city and the Chamber of Commerce partnered to launch Opportunity NOW, an initiative intended to create 10,000 paid summer jobs and internships for unemployed teenagers. In Boston, the city lured big fish GE from its longtime home base in Connecticut, beating out New York with an aggressive months-long, bipartisan, cross-sector city-state effort that focused on touting the city’s talent pool and offering massive tax breaks. Pittsburgh leveraged Carnegie Mellon’s Robotics Institute and eager government cooperation to enthusiastically welcome Uber’s research facility for self-driving cars, which — along with a thriving meds/eds scene — has helped spur a tech revolution.

You see where this is going. In a global economy, we shouldn’t just take cues from the competition. We should take ideas — and attitudes, and perspectives — that work and incorporate them into our city where we can. Who said innovation has to be homegrown? Nobody. And in a fight for our future, nothing’s off limits.

Published as “Philly’s Coming Job Crisis” in the June 2017 issue of Philadelphia magazine.