Philly’s Pension Board Is Finally Getting Its Act Together

After years of ineptitude, it’s now kicking its suburban counterparts’ butts.

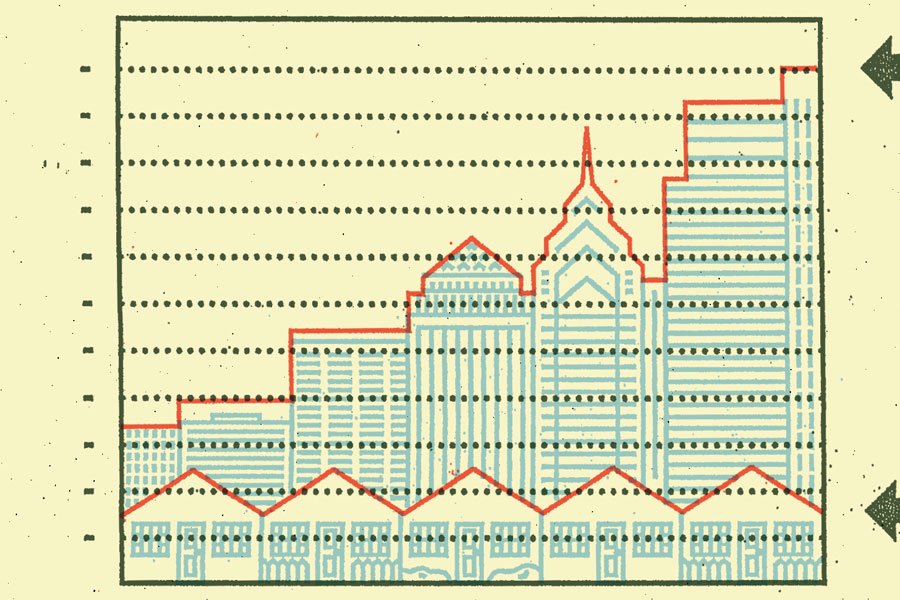

Is the Philly pension board actually getting its act together? Illustration by Pat Fennessy

It’s hard to believe, but it may finally be time to say something positive about Philadelphia’s much-maligned Board of Pensions. They’re the geniuses that gave us the Deferred Retirement Option Plan, or DROP — which rewards city employees with six-figure cash bonuses just for showing up during their final years on the job. This largesse has amounted to $1.5 billion over the past 20 years, draining a dangerously underfunded pension fund.

But as unlikely as it sounds, the pension board may be getting its act together — on the investment side of things, at least.

For years, the city spent tens of millions of dollars on so-called “active” investment managers — financial “experts” who were paid high fees even when they screwed up and lost millions of taxpayer dollars. Meanwhile, neighboring Montgomery County, long known for its financial acumen, fired all its high-priced active managers and beginning in 2014 switched 100 percent to “passive” index trading done more cheaply by computers.

For three years, from 2014 to 2016, Montgomery County’s investment returns averaged five percent annually — more than triple Philly’s same-period average of 1.5 percent. Pathetic, right?

But the city pension board actually did something about it. Beginning in 2016, it started firing underperforming pension managers and replacing them with much cheaper index funds. The result: a more than 50 percent drop in management fees.

In the 2014 fiscal year, when passive management of the city pension fund was at just 29 percent, investment management fees amounted to $33.5 million. Four years later, in the 2018 fiscal year, passive management had risen to 52 percent, while management fees had plummeted to $15.8 million.

Now who’s winning the battle of the pension-money investors? Philly, by a slight edge. After paying costs and fees, Philadelphia’s $5 billion pension fund posted estimated returns of 15.4 percent for calendar year 2017 and -4.2 percent during a rough 2018. Montgomery County posted net returns for its $481 million pension fund estimated at 14.7 percent for 2017 and -5.5 for 2018.

Another positive sign: Because of negotiated increases in employee contributions, a higher level of voluntary contributions from the city, and dedicated sales tax revenue — all paid to the fund on top of what the state requires — the city pension fund last year, for the first time in more than 20 years, had more money flowing in than out.

And the city continues to shed underperforming pension managers. At a February 21st meeting, the pension board voted unanimously to terminate the contract of AJO Partners. AJO was getting an estimated $133,505 this year to manage $44.5 million in pension funds. Among other concerns, in the past fiscal year to date, AJO had lost .7 percent of the city’s money, or $219,888, at a time when the city was expecting a return of 3.8 percent, or $1.7 million. AJO joined a hit list of 14 other underperforming active investment managers terminated by the pension board since 2016.

Despite higher fees, Philadelphia finance director Rob Dubow says, the city continues to value active managers who consistently hit or beat benchmarks after fees are paid. He cited the work of veteran managers such as Emerald Advisers of Leola, Pennsylvania, who are getting an estimated $503,785 this year to invest $80.6 million. Over the past decade, Emerald has averaged returns of 19.7 percent after fees. That’s two percent higher than the index fund that Emerald is benchmarked against.

Could Montco learn something from Philly? Stranger things have happened.

Published as “Many Happy Returns” in the June 2019 issue of Philadelphia magazine.