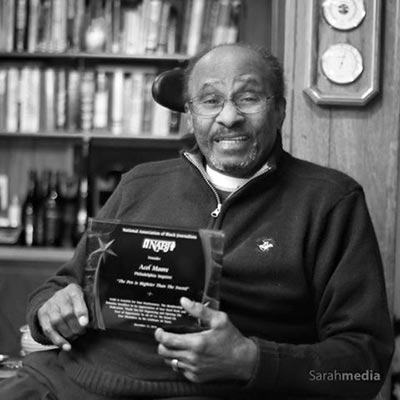

What Acel Moore Meant to Journalism — in Philadelphia and Beyond

Acel Moore. Photo | NABJ Facebook

The Civil Rights Movement and the riots that swept through dozens of American cities in the 1960s also exposed a hole in mainstream newsrooms across the land.

The white reporters and editors who staffed those newsrooms had little knowledge of the people who fueled the movement or the communities that erupted in rage.

To make matters worse, many of those reporters and editors didn’t know how much they didn’t know, because there was no one in their universe to tell them.

The Philadelphia Inquirer was fortunate to hire someone early on who could. That person was Acel Moore, who spent his entire career at the paper and died this past Friday at age 75.

Moore got his start the old-fashioned way: After high school (Overbrook) and a three-year stint in the Army, he got hired as a copy boy at the Inquirer in 1962. At that time, the paper had only one black reporter, and a group of ministers was threatening a boycott.

Moore’s lifelong dedication to ensuring blacks were covered and treated with respect by the mainstream media began with that hiring. He quickly made it clear that no one at that paper was going to address him as “boy,” as was the custom at the time, and after he drew his line in the sand, the use of the term faded away.

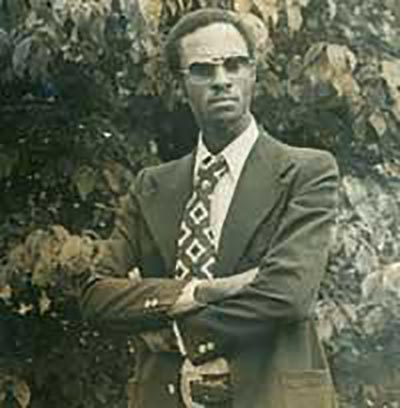

Acel Moore during his early years as an Inquirer reporter. Photo | Facebook

Moore also reported the old-fashioned way: He went out into the neighborhoods he knew and talked to people. His ability to ask the right questions and his respect for his sources made converts of cops who at first regarded him with disdain and got people who didn’t talk to reporters to talk to him.

His knowledge of the city and the African-American community enabled him to see how reporters and editors were getting the story wrong in the “long hot summers” of the 1960s. He took it upon himself to educate both fellow reporters and his editors on how to cover the black community accurately.

And he took it upon himself to push the paper to hire more minorities. And he took his concerns national as well, serving as one of the founders of both the Philadelphia Association of Black Journalists and the National Association of Black Journalists in the mid-1970s.

His ability to earn the trust of sources proved key to reporting his Pulitzer Prize-winning 1976 investigation into patient abuse at Fairview State Hospital in northeast Pennsylvania. And when he migrated across the line that separates reporters from opinion writers, he continued his advocacy for the ill-treated and ignored, especially his fellow African-Americans.

I didn’t know it at the time I was making my way into the profession as a copy boy (yes, we were still called that) at The Kansas City Star in the mid-1970s, but it was people like Acel Moore who opened the door and cleared away the underbrush so that our path would be smoother. But after he retired from the Inquirer after 43 years in 2005, those who followed the path he cleared let him know just how valuable his work was: He was showered with accolades upon his retirement, and the NABJ honored him with a lifetime achievement award at its national convention in Philadelphia in 2011.

Readers of this magazine know that we still need people like Moore around to keep us all honest. His guidance and influence will be missed by all of us who read, worked with, and knew him.

Follow Sandy Smith on Twitter.