This Punch Bowl Tells the Story of Old Philadelphia

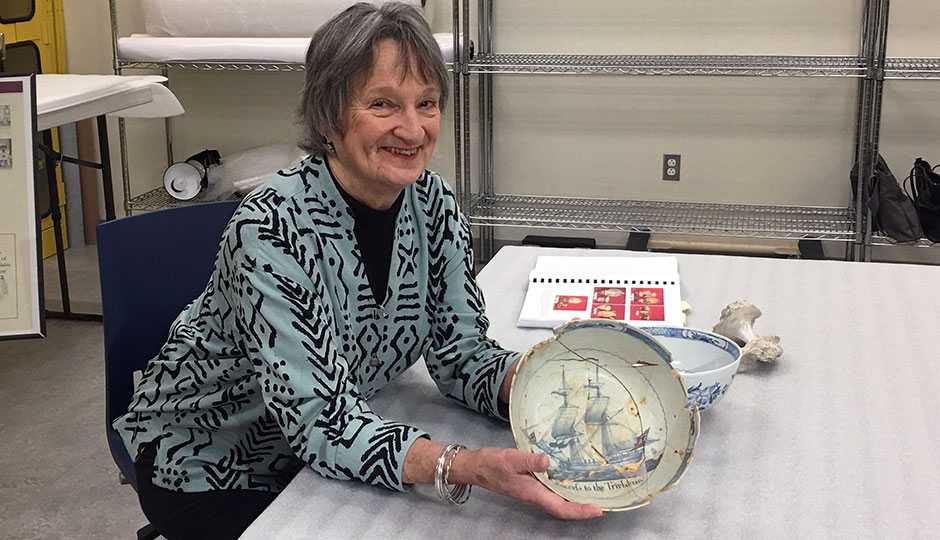

Rebecca Yamin, the lead archeologist on the excavation of the Museum of the American Revolution site, displays a reconstructed bowl from the 1760s that was found in a privy pit. | Photo: Dan McQuade

Rebecca Yamin first stepped onto the future site of the Museum of the American Revolution, at the corner of 3rd and Chestnut streets, in July 2014. She was both excited and scared.

“When you start at an urban site, it’s an amazing thing,” says Yamin, a well-respected urban archeologist with Commonwealth Heritage Group. “We told the museum it’s going to cost a lot of money. And then when I get on the site, I’m like, ‘Oh my god, I’m not going to find anything. It’s such an embarrassment.’”

When it was all over, Yamin did not end up embarrassed. Yesterday the museum, slated to open in April 2017, took possession of 72 boxes of artifacts, inside of which were 82,000 pieces recovered from the site.

“I’m always surprised,” Yamin continues. “Certainly we were surprised to find something that was so relevant to the mission of the museum.”

A bowl found at the site of the Museum of the American Revolution, and a replica created by Michelle Erickson after its discovery. | Photos: Dan McQuade

Yamin is referring to a punch bowl excavators found in a privy pit, and later reconstructed, from an unlicensed tavern on Carter’s Alley, which once ran parallel to Chestnut between 2nd and 3rd streets. It features the ship Tryphena, which in 1765 sailed from Philadelphia to Liverpool with a message from the city’s merchants asking Great Britain to reconsider the Stamp Act. That 1765 act led to some of the first major resistance against the British government in the colonies, and the phrase “no taxation without representation.” The act was repealed a year later, but the divisions remained.

Tavern-goers in the 18th century didn’t drink the way we did. Museum curator Mark Turdo explains the drink served out of the punch bowl was likely curdled milk mixed with brandy. This particular tavern was run from the front room of the house of Mary Humphreys, who was charged in 1783 with keeping a “disorderly house” — an unlicensed drinking establishment where men could pick up prostitutes.

Though she was found not guilty, she was somehow still sentenced to “be committed to the [jail] of this City till Saturday week next, and that on the said day She be carted through this City and that She be afterwards confined in the Workhouse at hard labour for three months, that She pay the Costs of this Prosecution, and stand committed, till this Sentence is complied with.” There’s no record of how she could be sentenced when she was found not guilty, but women were routinely targeted for this crime: While women ran only a quarter of the illegal taverns in colonial Philadelphia, half of the prosecutions for the crime were brought against women.

The story of Humphreys, and the story of that punch bowl, is the one the Museum of the American Revolution wants to tell. Yes, the museum will have extensive collections related to the Founding Fathers (including the pièce de résistance, the actual tent George Washington used as his headquarters in Valley Forge). But the museum also wants to focus on the everyday people who aided the war effort.

“This was an eight-year-old war, and it had impacts in every single community across North America,” museum president/CEO Michael Quinn says. “We really need to understand the revolution as something that was supported and sustained by everyday people. If it didn’t have that political will, it wouldn’t have been able to continue. Washington’s army did suffer many defeats. Many people suffered from occupation by the British, by marauding forces, by some of the vigilante groups, especially in the south — but the will to keep fighting was still there. These objects make that story apparent. And what’s wonderful is what these objects tell you: This is where that history happened. This is the old city of Philadelphia.”