The Cosby Show

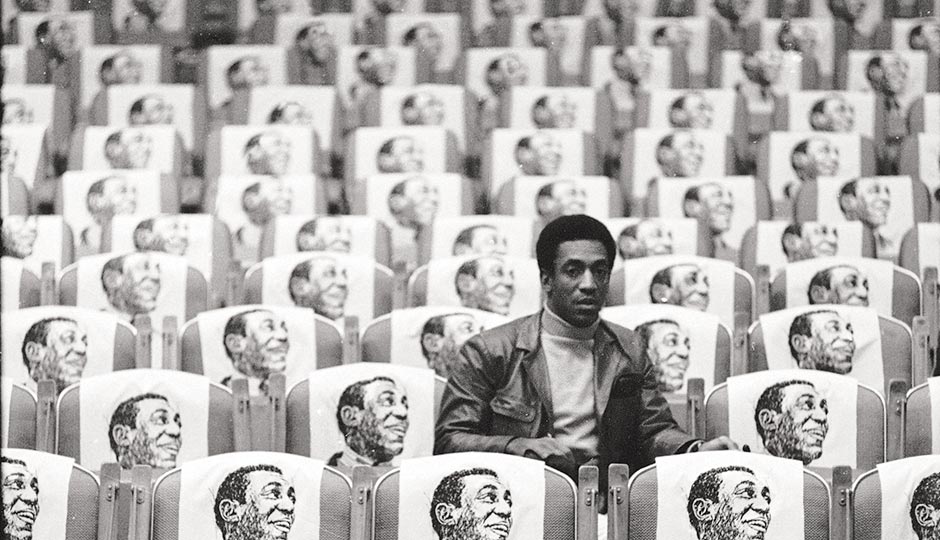

Photo via Michael Rougier/ The Life Picture Collection/ Getty Images

In the late summer of 1965, just before Bill Cosby’s espionage series I Spy debuted — with Cosby the first leading black man in a dramatic role to appear on network TV — a 17-year-old girl named Sunni Welles and her mother visited the Desilu set of the show. Sunni’s mother, a story editor at Paramount Studios and a talent agent, had gotten to know Cosby a bit; he’d broken through as a big-time comic a couple years earlier. He was a nice guy, funny and playful, especially with Sunni, whom he let sit in his chair with his name on the back.

Sunni herself was an aspiring singer and had already spent a good part of the preceding three years — since she was 14 — singing backup with various acts in Las Vegas and Carson City and other places.

Sunni’s mother couldn’t stay long, that day on the set of I Spy, but Cosby said Sunni didn’t have to leave; he’d look after her. What she says happened between the two of them is a story it’s taken half a century for her to be able to tell publicly.

Sunni told Cosby that she’d love to do her impression of jazz singer Nancy Wilson for him; she knew he liked jazz. Cosby asked Sunni how old she was. He said they could get together so she could sing for him, and he asked for her number. Later that day, Sunni’s mother told her not to be surprised if Cosby never called — he was a busy man. A few days later, Cosby called.

He had gotten the I Spy gig — playing opposite Robert Culp, with equal billing — largely on the strength of his preternaturally sunny persona. Cosby left Temple University to hit the New York comedy clubs in the early ’60s, essentially bringing to the stage a younger, peppier version of the Cliff Huxtable character he would play a couple of decades later; he riffed on the stuff of life, like weirdos on the subway, kindergarten, and driving in San Francisco. “A white person listens to my act and he laughs and he thinks, ‘Yeah, that’s the way I see it, too,’” Cosby had said a year before the debut of I Spy, in 1964. “Okay. He’s white. I’m Negro. And we both see things the same way. That must mean that we are alike. Right?” Cosby had crossover appeal long before basketball star Michael Jordan was given credit for inventing it.

The believable persona Cosby brought to his act cut both ways: The warmth of his slice-of-life comedy, on full display when Sunni first visited the set, didn’t just mesh with who he was — it was him. That was the leap, at any rate, that Cosby invited. And Sunni’s mother had been around him enough; she considered him a friend.

When Cosby called Sunni, he invited her out to Shelly’s Manne Hole, a renowned jazz club in Hollywood that he frequented. Sunni was thrilled — she wore one of her stage dresses that night. Cosby picked her up in his big black car; he looked sharp, in a turtleneck and black leather jacket. She sang for him on the way to Shelly’s; Cosby complimented her talent. When he suddenly put his hand on her leg, Sunni told him that she didn’t think of him that way. He was far too old — 28. “I didn’t mean anything by it,” Cosby said.

At Shelly’s, Sunni and Bill sat at a table reserved for them. From the time he was a boy with a cheap drum set, growing up in Philadelphia’s Richard Allen projects, Cosby had dreamed of jazz glory. Unfortunately, he wasn’t very good. But he was a famous comic now, and an enthusiast, and often went to hear Shelly Manne, who was a renowned drummer, play. Which meant that Bill Cosby bringing a very young girl — a white girl — to Shelly’s didn’t warrant a second glance, even in 1965. He was safe there.

Sunni ordered a Coke and remembers nothing else about that night.

What she does recall now is that the next morning, she woke up in a strange apartment, alone, naked in bed. The place was tiny, and there wasn’t much there: a desk, a phone. Her clothes — her stockings and girdle and underwear and dress — were scattered all over the floor. Sunni never would have left them like that, because her mother would have killed her. Even if she was drunk off her ass. Which in fact she couldn’t have been, because she didn’t drink.

Sunni got dressed and went outside in her bare feet in order to figure out where she was: Sycamore Drive. There was a beautiful view of the Hollywood Hills. Then she went back in and called a cab. When she made it home, she told her mother, “I think that Bill Cosby raped me, Mom.” Sunni’s mother replied, “Oh my God, no. That’s not possible. Are you kidding? No.”

Her mother didn’t believe what Sunni said could be true. The Cosby she knew couldn’t have done such a thing. She was sure it didn’t happen.

The wheel has turned.

We’re on the verge of a trial in Norristown, scheduled to begin June 5th, where the story of a woman named Andrea Constand will finally be told in court. It begins in 2002, when Cosby befriended her; Constand was director of operations for Temple’s women’s basketball. He became something of a mentor to her, and one night in January 2004, Cosby invited Constand to his home in Elkins Park, ostensibly to discuss her career. This is what she says happened next: She told him she felt stressed, and he offered her three blue pills — “herbal medication” — that soon rendered her semiconscious. She says Cosby proceeded to touch her breasts, rub his penis against her hand, and penetrate her vagina with a finger; she was too woozy to give her consent to any of that. Constand lost consciousness, woke at 4 a.m., and left Cosby’s house alone.

In 2005, then-Montgomery County DA Bruce Castor elected not to prosecute Bill Cosby over Constand’s claim that she had been sexually molested. “In Pennsylvania,” Castor said, “we charge people for criminal conduct. We don’t charge people for making a mistake or doing something foolish.” But new DA Kevin Steele, elected in 2015, ran on prosecuting the long-dormant case; scores of other accusations against Cosby were becoming public.

By now, 58 women, by the Washington Post’s count, from the mid-’60s up into this century, have come forward to claim Cosby sexually harassed or raped them, including dozens who say that he drugged them before their assaults. Now, after much legal wrangling, a jury will make a decision about Bill Cosby’s alleged behavior for the first time.

(Cosby has pleaded not guilty to sexually assaulting Constand. In 2014, a Cosby attorney said the accusations made by other women to that point were a “decade old” and “discredited.” Cosby did not respond to a request to comment for this piece and has not commented on Sunni Welles’s allegations.)

The Norristown trial, you might say, is bringing Cosby full circle, back home, given that he grew up in North Philly, raised primarily by his mother, Anna, who worked as a maid. Cosby’s father, William, had a serious drinking problem and was in and out of the Cosby home. Cosby first started trying out his comedy in tiny clubs in Philadelphia in the early ’60s before leaving for New York, and he always remained connected to this city. He still owns the mansion in Elkins Park, though now he spends most of his time at his homes in rural Massachusetts and New York. Over the years, he often performed wearing the sweatshirt of his alma mater, Temple University, and he was a regular at graduation and a longtime board member until he stepped down in late 2014, after the storm of sexual assault accusations hit.

But Cosby really got too big for Philadelphia a long time ago. It happened fast. After playing clubs in New York, he started performing all over the country, then made the award-winning comedy albums that led to I Spy. From there, his appeal, and importance, only grew, culminating in The Cosby Show in the mid-’80s. Almost from the first episode, Cliff Huxtable became Cosby’s finest creation. Here was a character so fundamentally real in his goofy appeal that we were certain we were getting to know Bill himself. Weren’t we?

As the patriarch of a loving upper-middle-class black family — another first for network TV — Cosby delivered a calling card in the form of not just what was possible for African-Americans, but what was true. He conceived the show and orchestrated pretty much every facet of it, and the Huxtables arrived, fully formed, with no explanation given. Here we are: The show would become his most important message on race. And, for that matter, on love.

When the torrent of women came forward with their accusations against Cosby, starting in late 2014, what was shocking was not only the allegations of drugging and rape they leveled against him, but also the sheer number of stories going back half a century, starting with that of Sunni Welles. The accusations cover almost his entire career. If his accusers are telling the truth, Bill Cosby lived an outrageous double life for as long as we’ve been enthralled with watching him.

Yet those two things — on the one hand the Cosby we thought we knew, the one with immense power and influence and seeming goodness, and on the other hand the sexual predator described by so many women — aren’t mutually exclusive. If Cosby was leading a double life, it worked in tandem. One part fed the other. Both sides of Cosby were building at the same time. And how that happened just might be the most shocking part of his story.

The night they spent together in 1965 didn’t end things between Bill Cosby and Sunni Welles. Sunni’s mother suggested she call Cosby to smooth things over. Sunni said she wanted to know how she had woken up in a strange apartment, alone, naked, her clothes strewn about.

“Oh my God, are you sure?” her mother said. She thought that Cosby would help Sunni in her career, and that asking so directly, confronting him … Sunni assured her mother she would simply ask him what had happened. “Be grown-up and handle it in a good way,” her mother advised. “Maybe you can sort it out with him.”

Cosby, in gearing up for I Spy, was under intense pressure. He had never acted before, and his initial attempts were mumbly and stiff; he had trouble remembering his lines. Meanwhile, America’s attitude on race was shifting, even as Southern stations and advertisers were calling NBC wondering if Culp and Cosby would actually be seen sharing bathrooms and meals in restaurants. Cosby had been getting heat all along, though, from some black activists for not having enough of a racial edge; they thought his get-along persona was borderline Uncle Tom. The atmosphere in L.A. in 1965 only ramped up that notion: In August, the Watts Riots in South L.A. — six days of looting and arson, resulting in 34 deaths — were triggered by allegations of police brutality. Still, Cosby’s charm and likeability — his easy appeal to the part of white America that could be swayed — were exactly what made the mainstream breakthrough of I Spy possible.

Sunni Welles, beautiful and blond, also came of age in a wildly shifting time. Youth culture hadn’t quite hit its full-scale hegemony over all things important, but L.A. was on the cusp. As a 12-year-old living in Pomona, Sunni would freely hitchhike to Newport Beach, her days her own; a couple years later, her mother moved Sunni to an apartment in Hollywood adjacent to Paramount Studios. By 15, she was frequenting clubs. She never got carded in Hollywood; Sunni looked much older than she was. But she wasn’t a girl of freedom so much as one of sophistication, a performer who could imitate Nancy Wilson or Barbra Streisand or Billie Holliday.

When Sunni called Cosby, after their night out, and asked him what happened, he said, “Don’t you remember the champagne Shelly sent over to our table?”

She didn’t. Cosby told her he had to let her sleep it off so her mother wouldn’t get mad at him for her getting drunk. Sunni wondered if she had undressed herself.

“Well, I didn’t,” Cosby said. He told her he rented the apartment from a buddy, as a hideaway where he could write.

Cosby wanted to take her out again, to the Magic Castle, a private club on a hill overlooking Hollywood. Sunni said yes, she would go, because she believed what Bill Cosby had said to her about the first night, and because her mother told her it was okay to go.

After her second night out with Cosby, Sunni says, she woke up in the same studio apartment, naked, her clothes strewn about, with a hole in her memory of getting there and what had happened. But she was sure of one thing, and this time, after Sunni didn’t come home the night before, her mother didn’t need convincing.

“My mother knew in her heart what had happened, and I did, too,” Sunni says. She is 68 now, and lives alone in Santa Monica with her foster cats. She’s barely scraping by. All of her adult life, she’s had trouble trusting men or sustaining relationships with them. “I don’t think my mother talked to Cosby after that,” she says. “But she never would have confronted him.” There was no way that would have done her, or Sunni, any good. In America in 1965, 17-year-old girls and their mothers thought long and hard before going to police to accuse men, especially men in the limelight, of sexually molesting them. “My mother,” Sunni says now, “was a woman of secrets.”

And for almost half a century, so was Sunni. Even in a world that was changing all around her, she didn’t think she had any way to address what she believed Bill Cosby had done to her.

The men who worked with Cosby on I Spy — the producers and directors and script guys were almost all men — are old now (or gone), and the Cosby they knew was distinct: “He was wide open and young and innocent,” Mark Rydell, a director who would go on to make On Golden Pond and The Rose, remembers. “He was a very sweet nightclub comedian.” Cosby performed for them — the kind of comic who craves attention, especially when he’s nervous about his acting chops.

There was plenty of spare time to fill, because I Spy was shot on location all over the world. Always, in every country, there was an American football to toss around. Out to dinner in Mexico, Cosby made a bet on who could stand the most hot sauce on the food; naturally, he won. Director Morton Fine was hard of hearing, and Cosby had a bit for the crew — speaking to Fine and then just pretending to speak, mid-sentence, then letting the words come, then mouthing silence again. He’d get Fine pounding the apparently faulty hearing-aid receptor in his chest pocket, a classic Cosby bit of silliness.

But another side of him showed up away from home. Jain Frye was 19, a girl from San Francisco who had foregone college to travel around Europe. In the summer of 1966, she and her friend met some I Spy crew members in Venice and were invited to work as extras for $15 a day.

After they moved on to Florence a couple weeks later — to film an episode called “To Florence With Love,” starring Joey Heatherton — Cosby came over to Jain during a break in shooting. “Hey, Beetle” — Cosby called her Beetle because, he said, she walked like cartoon character Beetle Bailey — “you are going to be my gofer from now on. If Bill Cosby wants something, you are going to go and get it for him.”

Later that day, Cosby said to her, “Bill Cosby wants to buy you a drink.” She told him she didn’t drink. “You will with me,” Cosby said. He took Jain to a cafe in the train station and ordered her a glass of black rum and nothing for himself.

“If Bill Cosby invites you for a drink,” Bill Cosby told her, “you are going to drink. You are going to chug it.”

“No,” Jain said. “I’m not going to throw up all over your nice Italian shoes.” She left the train station.

Cosby later told her they would meet at eight that night for dinner. A friend who was the set’s equipment manager told her not to go — that it wouldn’t end well if she did. He also told her that producer Sheldon Leonard and Fine had warned the crew that anyone responsible for Cosby’s very pregnant wife Camille, who was along on the Italian trip with the couple’s one-year-old daughter, hearing anything about Cosby’s womanizing would be fired. Jain stood up Bill Cosby that night.

A more complicated Cosby emerges in the company of men. For a year, Michael Elias wrote for The Bill Cosby Show, which ran from 1969 to 1971; Cosby played gym teacher Chet Kincaid. Elias also wrote for a Cosby variety show. He liked working for the comedian: “He was a reasonable, caring, listening guy. And I’ve never heard anything bad about him from people who have worked with him.”

Cosby could be intense, though. More secure of his place now — and not needing to perform for everyone around him — he didn’t like to be challenged.

He could also be generous. While Elias was writing for Cosby’s variety show, he got subpoenaed by a grand jury in Phoenix for harboring a fugitive from the Weather Underground — part of Elias’s anti-war activism in 1971. He had to tell Cosby why he’d be away for a few days. Cosby, Elias says, shared that he’d gotten a visit from the feds, who threatened to probe him for interstate gambling if he continued his anti-Nixon activism. “Take the time off, man,” Cosby told Elias. “With pay.”

The stories with women invariably seem to go in a different direction.

By the late ’60s, once I Spy had made Cosby a TV star, he could operate with great impunity. Celebrity photographer Tony Rizzo saw Cosby emerge from restaurants and clubs in L.A. “several times, I would say,” holding up some very young woman who was so incapacitated that she couldn’t walk on her own. Cosby told Rizzo, the first time or two, not to photograph them together, and Rizzo — who assumed the women were drunk — obliged him; Cosby was a married man, after all, and America’s paparazzi half a century ago were more decorous. At least, Rizzo was.

In 1969, a 19-year-old aspiring writer named Joan Tarshis met Cosby on the set of The Bill Cosby Show through friends of hers; when Cosby learned she was a writer, he invited Tarshis to his bungalow alone after one day’s shooting. In a lawsuit recently brought against Cosby, she says he made her a red-eye — a bloody Mary topped with beer — and the next thing she knew, she was waking up on a couch with Cosby removing her underwear. She told him she had a yeast infection — which wasn’t true — so, she says, Cosby forced her to perform oral sex on him.

Outwardly, the set of The Bill Cosby Show was “as clean as Caesar’s ass,” recalls Milton R.F. Brown, a writer. Elias remembers the same thing. No drugs. No shenanigans. That’s because Cosby, Brown says, as one of the first black men given his own show, was being watched very carefully by network suits.

Tarshis says she quickly fled L.A. for her parents’ home in New York. Cosby called her there a few months later. He was performing stand-up on Long Island. Joan’s mother answered the phone. She was a big fan of Bill Cosby, and he chatted her up.

As it turned out, Tarshis’s mother had no idea what her daughter now says happened to her in L.A. — Joan only told her about writing a bit for Bill, nothing else. Though of course, Cosby didn’t know that. If he had indeed assaulted Tarshis, his call tells us how little risk he thought there was in contacting her now.

On the heels of four consecutive Grammys for his comedy albums, with two albums of rhythm-and-blues vocals released, with cartoon specials in the works, with his own L.A. entertainment company releasing John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s Two Virgins album, with forays into the film world, and with his own sitcom airing: Risk? What risk? Being a black performer — which had made getting in the door in Hollywood a challenge — now played in his favor, especially given Cosby’s easy presentation; the growing segment of white America eager to establish its racial bona fides lapped him up.

Of course, Cosby’s growing star power wasn’t all he had going for him; half a century ago, rape was largely a crime to be kept under wraps by everyone, especially the victims. It was an era in which Cosby could do a bit on the wonders of Spanish fly on his 1969 album It’s True! It’s True!, breezily describing how he looked for the legendary aphrodisiac while he was on location in Spain filming I Spy.

Joan Tarshis had no doubt that powerful men in L.A. could make problems go away. She convinced herself that if she came forward, accusing Cosby of raping her, he would simply have her killed. “That I would end up at the bottom of a canyon in L.A.,” she says now, “and that no one would ever know who did it.”

Cosby’s call to Joan’s household was rewarded. Joan wasn’t going to disappoint her mother, Bill’s fan.

Joan would get picked up by his driver and go to his show. That night, she says, Bill Cosby drugged and raped her once again.

By the mid-1980s, Bill Cosby needed something new.

Moving east from L.A. to bucolic Massachusetts in late 1971 had signaled a man of more gravitas; Cosby would create the Fat Albert Saturday-morning cartoon for kids, bestow the letter E (for excellence!) as the first letter of the name of each of his five children, and begin work on a doctorate in education at the University of Massachusetts. Cosby had never been a mere comic; always, along the way, that persona was building his brand. Meanwhile, he often roamed west — to Vegas and back to L.A., especially — spending hundreds of nights a year performing as a family man of unimpeachable values.

Photo via New York Daily News/Getty Images

Cosby’s friendship with Hugh Hefner — and his visits to the Playboy Mansion in L.A. in the 1970s and beyond — would provide a safe haven; for several years, Cosby was a ubiquitous presence there. “The whole Quaalude thing, that came from my father,” Jennifer Saginor says. Her father, known as Dr. Feelgood, was Hefner’s personal physician, and Saginor has written a book about how she essentially grew up in the mansion. (In a deposition for a civil suit Andrea Constand filed against Cosby in 2005, Cosby admitted procuring Quaaludes to give women consensually, “the same as a person would say have a drink.”) Cosby was part of Hefner’s inner circle. P.J. Masten, a Playboy bunny in Chicago, has claimed that in 1979 Cosby raped her; when Masten told her supervisor what had happened, she said, “Well, you know that’s Hefner’s best friend, right?” Masten said her supervisor told her to keep quiet about it. Masten went on to supervise bunnies in Chicago, and she has said that a dozen bunnies have told her that Cosby sexually molested them, too, but most were afraid to come forward.

Now, though, in the mid-’80s, as Cosby was heading into middle age, rich from all the stand-up performances and from pitching Jell-O and Ford and other products on TV — he was so convincing as a salesman that newsman John Chancellor pronounced him America’s most effective communicator — it felt as though his time had passed. His brand was still strong, but he’d lost his edge. His last three TV series had failed. He would no longer be really large. Or it. But Cosby sent word, through his agent, to Hollywood: He wanted to take another shot. Bill needed to re-create himself.

Initially, Cliff Huxtable was going to be a limo driver. Imagine the fun he could have, the characters he’d pick up! But Camille Cosby quickly nixed that; how would his fans believe that Bill Cosby was a limo driver? So he took his character in another direction: He’d play a doctor. His wife would be a lawyer. They’d live in a sweet brownstone in New York.

With that, Cosby could give Cliff some of his real interests: African-American art, which adorned the walls of the Huxtable home. And his beloved jazz for the soundtrack. Cosby picked the furniture and even had a say in the cast’s clothes, especially the outrageous sweaters he wore.

Most important, Cosby imbued Cliff with the rich silliness he had been crafting for 25 years, which created a useful paradox: Cosby up on stage was clearly performing, creating and enlarging stories of family life, taking them to absurd extremes, whereas Cliff was living them. He and the other Huxtables became the real-life embodiment — or so it seemed — of the family Cosby had more or less dreamed up in his act.

Meanwhile, Cosby had another strategy certain to conflate his reality with Cliff’s. He took pains to explain publicly how things on the home front — his actual marriage to Camille — had evolved.

“More than anything,” Cosby told Playboy during the show’s second season, “I know how happy I am at home. My wife, Camille, and I are enjoying each other more and more, mostly because in the past eight or nine years, I’ve given up all of myself to her.” Cosby had taken to wearing a bracelet with a printed message, for anyone who cared to notice: CAMILLE’S HUSBAND. “I’m no longer holding anything back,” he said. “It’s just pure and good with us.”

Meanwhile — because there always seems to be a meanwhile in Bill Cosby’s story:

Beth Ferrier came to New York from Chicago for a week to drum up modeling work in the fall of 1984. Cosby, who knew her Denver agent, kept inviting Beth to dinner, to his brownstone to discuss her career and to help him pick out which sweater he should wear for his show.

Initially, she wasn’t taken with him. He was 47, she was 24; they were both married, and she had a young child. These markers struck her as an unbridgeable divide, so nothing would happen. Anyway, Beth was making 10 grand some months as a model — she didn’t need Cosby.

She watched rehearsals for the show. Bill was wonderful with the children, and with Phylicia Rashad, who played his wife, and you could sense that any script was often beside the point — the way Cosby could create a family, right before her eyes, felt to Ferrier like maybe the best theater she had ever seen. As if she had been invited into the safest place in the world.

She certainly wouldn’t be alone in falling for the Huxtables’ warmth. But eight years of Cosby also shifted racial dynamics in America and internationally — for a time, it was the most popular TV show among whites in apartheid South Africa — and would have a role in opening the door two decades later for Barack Obama. Stanford’s Shelby Steele captured the show’s effect in Harper’s in 1988: “The bargain Cosby offers his white viewers — I will confirm your racial innocence if you accept me — is a good deal for all concerned. … The power that black bargainers [like Cosby] wield is the power of absolution. On Thursday nights, Cosby, like a priest, absolves his white viewers, forgives and forgets the sins of the past.” Not everyone agreed that this was a good thing; to other black thinkers, like playwright August Wilson, Cosby’s creation of such a successful family did great harm in skating over the reality of most African-American lives in this country. It’s certainly true, though, that in creating a black family utterly self-possessed in its success, Cosby had delivered something brand-new to much of America, and now he breathed rarefied air.

Beth would keep coming back. To see the show being made, and to see Bill Cosby. They would have an affair for almost two years. At the end of it, she says, when she was trying to leave him, when he had been calling her endlessly, and calling her mother, and calling her brother, when she could not get rid of him, he made her a cappuccino in his dressing room at a theater in Denver, where she lived, before a performance there. The next thing she knew, she woke up in her car in an alley, her clothes a mess. Cosby, Beth Ferrier says, had raped her.

Bill Cosby’s fall from grace has made all the good he really did do seem so distant and maybe meaningless, especially the larger impact of The Cosby Show. But throughout his long career, Cosby had often given in smaller ways. He took obvious delight in hiring African-Americans to staff his shows and in finding work for old talents like jazz percussionist Willie Bobo. And he gave in not-so-small ways: He and Camille donated vast sums of money to bolster education, culminating in a $20 million gift to Spelman College in 1988. But one initiative, ostensibly to help the country’s urban underclass, would contribute to his undoing. It began with a speech he gave in May 2004.

Cosby spoke at Washington’s Constitution Hall when he received an award for philanthropy at an event commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Brown v. Board of Education decision. He said that the poor in America were “not holding up their end of the deal.” He said that parents “cry when their son is standing there in an orange [prison jump] suit,” but the reason he’s there in the first place is lousy parenting: “Where were you when he was two? Where were you when he was 12? Where were you when he was 18, and how come you didn’t know that he had a pistol? And where is his father?”

With that, Cosby was off and running, flying all over America in his Gulfstream jet, appearing at lecture halls not to tell jokes, but to reprimand mostly inner-city black men for the miserable state of their lives. Reaction to his callouts ran the gamut: Cosby, attacking his own people from the safe perch of vast wealth, was cruel and way off the mark; or he had the cojones to go right up the gut of what desperately needed to be said. Mostly, Cosby got hammered, especially by black intellectuals like Michael Eric Dyson, for something that had dogged him his whole career: He was pandering to his white fans. In this case, conservatives presumably would eat up Cosby’s pull-up-your-bootstraps demand.

The display did seem strangely fueled by rage — Bob Culp, his co-star on I Spy, once said Cosby was the angriest man he ever met. Cosby, of course, had overcome a great deal himself in growing up in Philadelphia’s projects. And he proclaimed, long ago, what he wanted his career to stand for: “It doesn’t mean anything, if you can’t take what you know and make America a better place.” We felt that desire, so palpable throughout his long career.

But the demand he seemed to be making now felt … off. He was angry. As if the plight of inner-city America was a personal affront to Bill Cosby.

You wondered if he had lost his bearings. Cosby had been through a terrible patch in the late ’90s: A woman named Autumn Jackson, claiming to be his daughter, tried to extort $40 million from him in 1997, and he admitted to a “rendezvous” with Jackson’s mother and payments of more than $100,000 in support over the years. The same year, Cosby lost his only son, Ennis, to a random roadside murder in L.A. For a moment it seemed he was like the Kennedys — that bizarre and terrible things would naturally befall a life that had reached such outsize proportions.

Then, in ’05, the Andrea Constand allegation, the one that has him facing a trial now, first bubbled up. Constand had filed her civil suit against Cosby, and 13 women who also claimed to have been molested by him — with nothing to gain, past the statutes of limitation that would have let them sue him — were ready to testify. It appeared then that he might be in serious trouble. But Constand settled, and even as three of those 13 — Beth Ferrier, Tamara Green and Barbara Bowman — told their stories publicly, nothing changed for Cosby. Why? Why did we ignore the women then, with our appraisal of Cosby suffering nary a dent? The obvious reason is that we don’t do a very good job of listening to women who claim they were sexually abused. But there’s another, trickier answer: We were far too attached to Bill Cosby — especially to the idea of him as America’s Dad, amped up for white fans with the good feelings on race that Shelby Steele had written about. And we were attached as well to our presumed intimacy; we certainly didn’t want to believe that his abuse of women could be true — not Bill. No way. We were collectively as naive and unwilling as Sunni Welles’s mother had been in 1965.

Yet Cosby was now undermining himself, because he had begun to overplay his hand. He had started, in other words, to use our grand view of him and the power that bestowed in an increasingly reckless way. Tamara Green, who claims that Cosby sexually assaulted her in California in the early 1970s, understood a decade ago what would eventually happen, because Cosby would take his public posturing too far. “I knew [the sexual abuse] would emerge again because he’s so arrogant,” she said in 2005. Green also said, a decade ago, “He did a lot of good works behind which he could stash his crimes of excess.”

Even though he initially got past the Andrea Constand accusation, Cosby would keep speaking from on high, from the platform of “Bill Cosby,” and that’s what would eventually do him in. Comedian Hannibal Buress, in a performance at the Trocadero in Philadelphia in late 2014, accused him of being a rapist, though Buress seemed most enraged not about what Cosby had done to so many women, but about something else: that Cosby would have the audacity to tell him how to comport himself, as a young black comic — another piece of Cosby’s arrogance coming home to roost.

Buress’s performance at the Troc went viral. Social media did the rest. Suddenly no one could ignore the possibility, at least, that Bill Cosby really had done some heretofore unspeakably bad things. And maybe, a decade later, we were a little more ready to take on what women were saying about him.

At any rate, it happened. The door had opened a crack, and almost 60 women pushed right on through.

Bill Cosby hasn’t been convicted of anything. That’s an important point to remember as we await his trial. But if we back up half a century, and consider one more story — one that Cosby has denied in court — we can see how things have changed.

In December 1965 — I Spy had been on the air at that point for three months — a 22-year-old woman named Kristina Ruehli, a secretary at a talent agency in Los Angeles that Bill Cosby frequented, was invited by him to his home one night for a party, along with the agency’s other secretaries. Only Kristina and one other woman showed up. Kristina says she passed out after Cosby gave her two drinks. When she regained consciousness, she was naked in bed with Cosby. (The other woman was nowhere to be seen.) He was trying to push his penis into her mouth and force her to perform oral sex, she says. Kristina was able to escape to the bathroom, where she got sick, then find her clothes and leave Cosby’s house early in the morning.

Kristina went to work that morning at the talent agency, and she immediately asked another secretary there — a woman she was close to, someone with whom she’d spent time outside of work and shared her personal life — “What happened to you guys last night? When I got to Cosby’s house, none of you were there.”

And the other secretary did something odd: She looked down and started rearranging her pencils, not even acknowledging what Kristina had said, though it was apparent to Kristina that she had heard her. It struck her as a strange response, until Kristina realized, many years later: The secretary, in turning away, showed that she knew something, but it wasn’t knowledge that could be shared, even among young women who were close friends and had previously shared a great deal. This was too dangerous. Because what had happened the night before at Bill Cosby’s house — and clearly the secretary had ideas about that, and perhaps a story of her own — immediately bore in on them, on what sort of girls they were, and could not even be discussed.

In the end, Bill Cosby’s guilt or innocence, about to be decided in a courthouse in Norristown over one woman’s accusation, isn’t really the bottom line of his long saga. The women are — the ones who have come out and told their stories about what they say happened with him. It might seem like we still have a long way to go, especially in the way that powerful men often relate to women in America. But we have, at long last, made it to a messy, important place. We have finally reached the point of discussion.

Published as “The Cosby Show” in the June 2017 issue of Philadelphia magazine.