Why the Gutting of Civil-Forfeiture Reform Matters to All of Us

Photo: istock/baona

A former cop recently reminded me about an old Upton Sinclair line that just about fits Pennsylvania’s maligned civil-asset forfeiture policy perfectly: “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

That conflict is at the heart of ongoing political and legal efforts to improve a law-enforcement practice that, in its current form, would make a third-world dictator feel all warm ’n’ fuzzy. Authorities have long been able to seize a person’s property if they merely suspect it’s connected in some way to a crime. Think about that: You could lose your house — or even your kid’s piggy bank — without ever being charged with a crime, let alone convicted. The kicker? The proceeds end up helping to fund the very agencies that seized your stuff. (If you listen closely, you can almost hear someone singing a couple of bars of the “Circle of Life.“)

There are horror stories about this stuff happening across the country, but even Kafka wouldn’t know what to make of the episodes that play out around here. Philadelphia in particular has long been singled out by experts for its punishing civil-asset forfeiture efforts, which scooped up more than $64 million in funds from its citizens between 2002 and 2012, according to the Institute for Justice, and left them with little recourse to fight back. Imagine, then, the hope that people felt in June 2015, when state Senators Mike Folmer and Anthony Williams co-sponsored a bill that sought to set new, saner guidelines across the commonwealth. Republicans and Democrats, working together! Huzzah!

Senate Bill 869 proposed a number changes to the civil-asset forfeiture system. The most significant: A person’s assets couldn’t be permanently seized unless he was actually, you know, convicted of a crime, and any proceeds would have to end up in a city or county’s general fund instead of the hands of local law enforcement. New Mexico and Montana already made similar landscape-shifting moves, and support for the reform efforts has made strange bedfellows out of the American Civil Liberties Union and conservative billionaire Charles Koch.

“I do not believe people should lose their property when they haven’t been charged with or convicted of a crime,” Folmer wrote when the Senate bill was introduced. But the bold plan fell apart like a snowman on Memorial Day. After intense lobbying by the Pennsylvania District Attorneys Association, the bill was modified last month to remove the most meaningful provisions. A watered-down version was then passed by the Senate and is now in the hands of the House Judiciary Committee. “Some people will argue it’s better than nothing, which is true, but it’s not much more than that,” said Williams, who was deeply unhappy with the final product. “But for those people who lose their property and have never been arrested, never been found guilty and still lose their belongings, it’s not fair.”

The consensus from some of the people who were involved in behind-the-scenes discussions (more on that in a bit) is that this bill is a first step, that more ambitious legislative reforms can follow. No one’s putting a timetable on that, of course; who knows what the political landscape will look like after Election Day? But Philly’s forfeiture system could end up getting a meaningful kick in the pants next year, thanks to a long-simmering local court case.

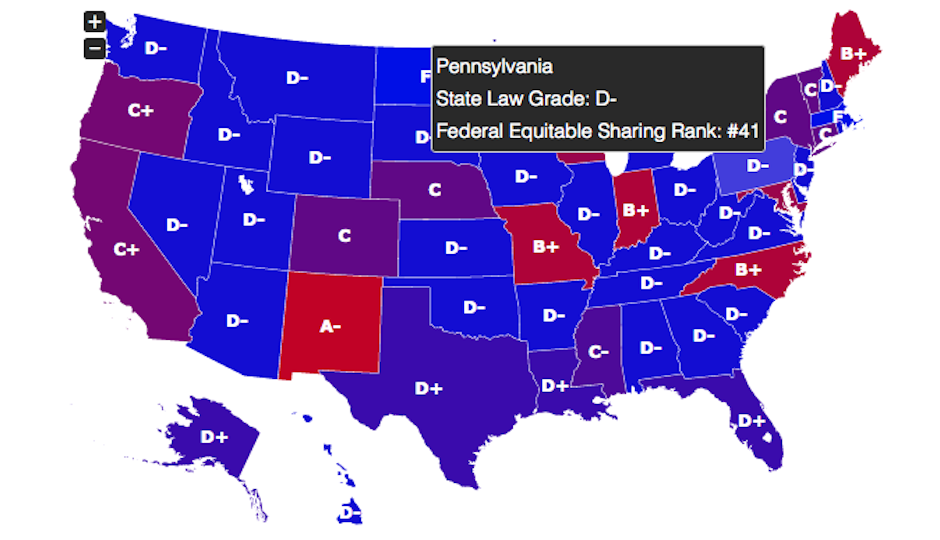

The Institute for Justice gives Pennsylvania a D- for its forfeiture practices.

IT’S BEEN A LITTLE MORE than two years since the Institute for Justice and the law firm of Kairys, Rudovsky, Messing & Feinberg took Philadelphia to federal court over the District Attorney’s Office’s civil-asset forfeiture practices.

Christos Sourovelis and his wife, Markela, are the lead plaintiffs in the lawsuit; the D.A.’s Office seized their Northeast Philly house — boarding up the doors and windows, shutting off the utilities — after their 22-year-old son was arrested for selling $40 worth of drugs to an informant in front of their home. It was their son’s first arrest, and there was no evidence the parents had anything to do with the minor drug transaction. (The D.A.’s Office ultimately dropped the forfeiture cases against Sourovelis and another plaintiff in the federal lawsuit, Doila Welch.)

That a family could be booted out of their house with little notice and no opportunity to dispute the D.A.’s Office’s actions came as no surprise to anyone who paid attention to former City Paper reporter Isaiah Thompson’s 2012 investigation into the civil-asset forfeiture system. Thompson found that the Philly D.A.’s Office filed hundreds of petitions to forfeit properties every year, and thousands of petitions to seize cash, hauling in about $6 million annually, a large chunk of which is spent on salaries. The prosecutors’ goal might be to bust criminal enterprises and drug kingpins, but plenty of average citizens get sucked into the forfeiture world.

“They have a perverse incentive to forfeit as much property as possible, and over the years, they’ve done it in violation of the Constitution,” said attorney David Rudovsky. “It’s a little bit of a gravy train.” Last year, as part of the lawsuit brought by Rudovsky’s firm and the Institute of Justice, the D.A.’s Office agreed to make some changes to its program, like limiting its practice of barring homeowners from properties they’re fighting to get back and placing restrictions on property owners in settlement deals, the Inquirer reported.

But Rudovsky said a bigger decision could loom next year. U.S. District Judge Eduardo Robreno will have to decide if the civil-asset forfeiture policy represents a conflict of interest for the D.A.’s Office, since it benefits financially from the assets it seizes. “At a minimum, that would mean that the current process is unconstitutional as a violation of Due Process of Law rights and that the proceeds of forfeiture would have to be part of the city’s general fund or some other non-conflict arrangement,” Rudosky wrote in an email. “There is also a question as to whether the D.A. would have to return certain property seized under this process.”

The D.A.’s Office declined to comment for this story, but District Attorney Seth Williams contended in an op-ed in the Inquirer last year that the program is a force for good, disrupting drug trafficking operations and seizing ill-gotten cash. Richard Long, the executive director of the Pennsylvania District Attorneys Association, echoed Williams’s argument. “The program provides important resources [prosecutors] use to help combat crime and improve public safety across the commonwealth,” he said, adding that in some counties, funds seized through civil-asset forfeiture are being used to provide cops with naloxone to treat drug-overdose victims.

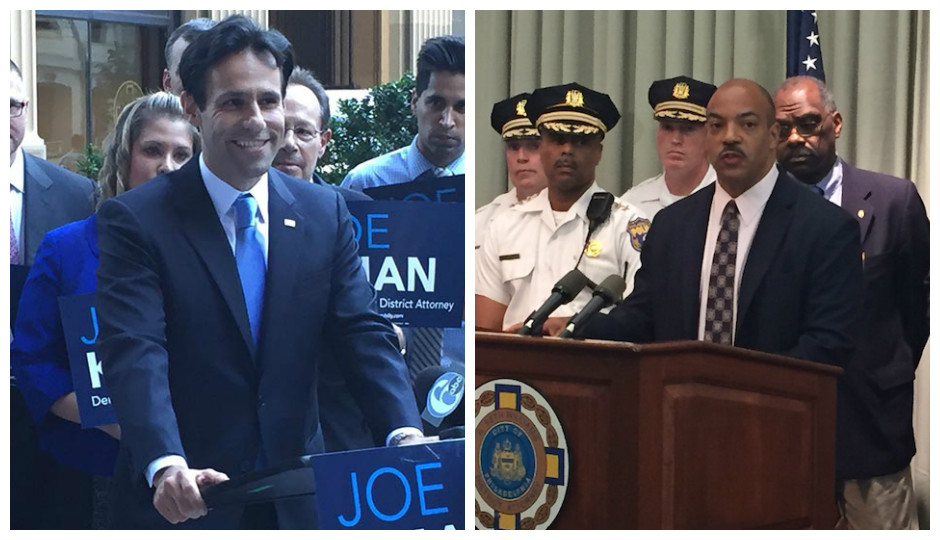

Expect the issue to bleed into Williams’s 2017 re-election bid. Former federal prosecutor Joe Khan, who last month announced plans to challenge Williams in the spring Democratic primary race, didn’t hesitate to weigh in. “There are ways to achieve goals that are probably laudable without having a scorched-earth approach that basically leaves a lot of people homeless and penniless, and in a much worse situation that they need to be,” he said. “As I see it, the District Attorney’s Office’s use of civil forfeiture suffers from some of the same problems we’ve seen elsewhere, which is the D.A. not understanding or grasping the difference between situations where you can do something versus situations where you should do something.”

Former federal prosecutor Joe Khan (left) will run against District Attorney Seth Williams in the 2017 Democratic primary race.

SO WHAT THE HELL happened with that Senate bill, anyway?

Fred Sembach, Mike Folmer’s chief of staff, said Senate leaders, the District Attorneys Association, the state Attorney General’s Office and Fix Forfeiture — a bipartisan nonprofit that receives funding from Koch Industries — were all involved in discussions that shaped the final bill. The much-hyped provisions — to require a criminal conviction for an asset to be seized and for seized money to end up in a general fund — proved to be “a big sticking point,” he said. It seemed wiser to take a smaller victory now than throw the baby out with the bath water entirely and redo the bill from scratch.

Sen. Williams saw his peers wilt under pressure from the D.A.s Association. “You heard a lot of, ‘I want to support this, but my local district attorney is pretty popular…'” he said, as his voice trailed off. “Yes, I think a lot of our members did reach out to their legislators and voice the importance of civil-asset forfeiture in their individual county,” Long said. In its original form, the bill “would have allowed proceeds and money that were a part of criminal enterprises to remain in the hands of those that were committing crimes or facilitating criminal activity,” he said. “We think the changes that were made were helpful.”

Senate leaders are hopeful the amended bill — which raises the burden of proof prosecutors must meet when they’re seeking to seize a person’s assets, and requires more thorough reporting on seized assets — will come to a vote during the current legislative session. Jenna Moll, Fix Forfeiture’s deputy director, said the bill also provides more clarity on how people can get their property back if it’s been wrongfully seized. The changes are a step in the right direction — but not enough. “That’s why we feel so strongly about the conviction requirement,” she said. “If you had that, people would feel a lot more comfortable with having proceeds go to law enforcement. This legislation doesn’t get us there yet.”

In the meantime, pray to God your kid doesn’t get caught selling a couple of joints in front of your house.

Follow @dgambacorta on Twitter.