The Philadelphia Folk Festival Is Hanging On By a String

The venerable, star-launching music fest is gearing up for its 60th installment. Unless its organizers make some changes, and quickly, this could very well be its last dance.

Margo Price plays the Martin Stage at the 2019 Philadelphia Folk Festival / Photograph by Jonathan Wilson

Pinch me. There was Judy Collins, love of my seriously folked-up teenage life, sitting alone under a willow tree on the Wilson Farm at the third annual Philadelphia Folk Festival in the glorious summer of ’64.

“M-m-m-mind if I join you?” I asked nervously.

“Please do,” she said, and smiled.

I dropped my guitar case — mostly toted around the grounds to signal I was a bit of a “playa,” too — and sat. Then we talked, maybe for 10 minutes, before it was time for her to go. Honestly, I can’t remember anything I might have asked or said beyond, “I love what you did with ‘Turn! Turn! Turn!’” (from her then-new album #3). But the easy aura of approachability, kindness and concern she exuded would stay with me forever — underscoring what I always liked so much about the down-to-earth folk music scene here. And the deep gaze I took into her, ahem, sweet Judy blue eyes that September afternoon? That image is burned into my brain, an unforgettable memory.

Of late, reminiscences like that have been haunting me as the Philadelphia Folk Festival (PFF) gears up for a big 60th-anniversary gathering of the tribes this August 18th to 22nd. It’s an event I’m anticipating with both elation and a bit of trepidation.

For sure, it’ll be a wonderful chance to reunite with Fest friends, walk the grounds, eat fun food, check out crafts, and take in the likes of Michael Franti & Spearhead, Hiss Golden Messenger, Bettye LaVette, Dom Flemons, Tom Rush and Livingston Taylor on a crystal-clear sound system. And, when the tunes get pumping, to align anew with the spirit of Mr. Tambourine Man, to dance beneath a diamond sky with one hand waving free.

But on a very down-and-out side, this 60th get-together feels like it could be a last hurrah of sorts. For reasons demographic, competitive and structural, the Folk Fest — the long-running multi-stage August event in the Philly ’burbs, with a proud history of breaking acts in the broadly defined world of folk music — has been running on empty in recent years: losing money most summers, incurring hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt, forcing its nonprofit parent — the Philadelphia Folksong Society (PFS) — to take out loans and sell off assets just to stay afloat.

While hardly the only local arts organization in the red, PFS has to be the most readily gossiped-about and critiqued by its membership (lately numbering around 850) and the large coterie of 5,400 Fest-attending “friends” who participate in the festival’s unofficial Facebook site, Philly Folk Fest.

Last summer, the rumblings of financial distress grew louder. The Fest was forced by COVID-19 — and probably the weak ticket sales I was tracking — to go strictly online for a second year in a row, this time with a “pocket-sized” two-day PFF that organizers dubbed “59½ Annual.” (Couldn’t waste a nice round number on the dinky thing.) And that’s when I really panicked. I bought my way into the streaming Fest, of course. I also renewed my membership in the Folksong Society and threw money into the general donors’ fund. And I persuaded myself to buy an overpriced festival t-shirt in maroon (my least favorite color) from the online store because the garment was prematurely (and wishfully) printed with a 60th-festival logo. “Could become a collectible,” I thought, perversely, “if the Fest doesn’t actually survive to the summer of 2022.”

A month later, a minor miracle: PFS was salvaged by a fat infusion of COVID relief money — $869,254 from the Shuttered Venue Operators Grant program. But that pot of gold isn’t bottomless and has largely been dumped out already to pay off past debts — and it won’t be refilled. So if music fans don’t rally en masse to the Old Pool Farm in Schwenksville for Folk Fest 60 — and if the festival can’t finally adjust to some long-in-the-works music-industry trends — we may all be whistling the bittersweet blues that Dave Van Ronk and David Bromberg used to perform out there: You’ve been a good old wagon, Daddy, but you’ve done broke down.

“I hate to be the bearer of bad tidings. I really wish them well,” says Scott Rovner, a “mostly retired” private banker who’s tracked the travails of and sometimes advised the Folksong Society. “But the Philadelphia Folk Festival is one rainy weekend away from total demise as we know it.”

As a “lifer,” I can’t say I haven’t had a good run at the Folk Fest — haven’t dug it from both sides now, as Joni put it. I’ve lived it as a teen, a young adult, a middle-ager and, egads, a senior. I’ve been a music fan and player and then a music chronicler — paid to edit a few festival program books, contribute historic liner notes for the 40th-anniversary CD box set, and cover the scene for decades as the music writer for a (once) major metropolitan daily.

Still, who wants to see a party end? The Philadelphia Folk Festival is in a tough spot — partly its own doing, and partly a result of sea changes in the music industry. Its cooperative, tradition-bound structure has made adapting a challenge. Is there still time? A new event coordinator, experienced in running successful festivals elsewhere, has been hired to shake things up and make changes that will surely annoy some longtime regulars but will hopefully do the trick of saving a cultural institution that is, by many accounts, just hanging on by a worn banjo string.

My obsession with folk music started when I was a kid of nine and 10, spoon-fed on “Red River Valley” and “This Land Is Your Land” at the Miquon Day Camp in Conshohocken, where I sang and strummed the baritone ukulele under the tutelage of the late music instructor George Britton. A hearty bass-baritone balladeer and actor (of Irish and Pennsylvania Dutch descent), Britton was instrumental in the founding of the Philadelphia Folksong Society in 1957, the Philadelphia Folk Festival in ’62, and, in 1965, an all-ages coffeehouse with live music in Bryn Mawr, called the Main Point — a venue where many a future star would first shine. I recently learned that Folk Fest mainstay David Baskin — event chair or co-chair for many moons (from 1965 to 2009) — also caught the folk flu from Britton at Miquon.

Just slightly ahead of the curve, I watched folk music become a dominant part of the contemporary music industry. Harry Belafonte’s 1956 album Calypso was the first LP of any stripe to sell a million copies. In ’62 and ’63, Peter, Paul and Mary recordings introduced millions to the music of Bob Dylan (“Blowin’ in the Wind”) and Pete Seeger (“If I Had a Hammer”). The folk scene grew so big that ABC broadcast a prime-time Hootenanny every Saturday night from 1963 to ’64 — always must-see TV at my East Falls home.

Fueled in part by my mom and dad’s commitment to the civil rights movement, I went to freedom marches and wrote (not-so-great) protest songs to sing in high-school assemblies and then as an undergrad in a campus coffeehouse at Penn. I wasn’t much good, but I found a voice as a music reviewer/advocate — initially for the Distant Drummer underground weekly, then as the first popular-music critic hired by the Philadelphia Daily News — a two-year commitment that ultimately lasted 47.

Lucky me, I turned 16 just six months before the very first Folk Festival. That meant I could drive myself in Mom’s station wagon to the C. Colkett Wilson Farm in Paoli. My then-guitar teacher, Tossi Aaron, was a Folk Fest organizer and performer. She shared how the event came together in ragtag “Let’s put on a show!” fashion and sold me my first all-Fest ticket ($4), which proffered two days of workshops (glorified round-robin sings), a banjo contest and one evening concert. Jeez, I loved those first four years on the Wilson farm. The setup was so small and loose and democratic, with musicians strolling around the grounds (like Ms. Judy) and readily approachable, since there was no sequestered backstage area. Banjo man Roger Sprung convened pickup jams in the parking lot, and even little me was welcome to strum along.

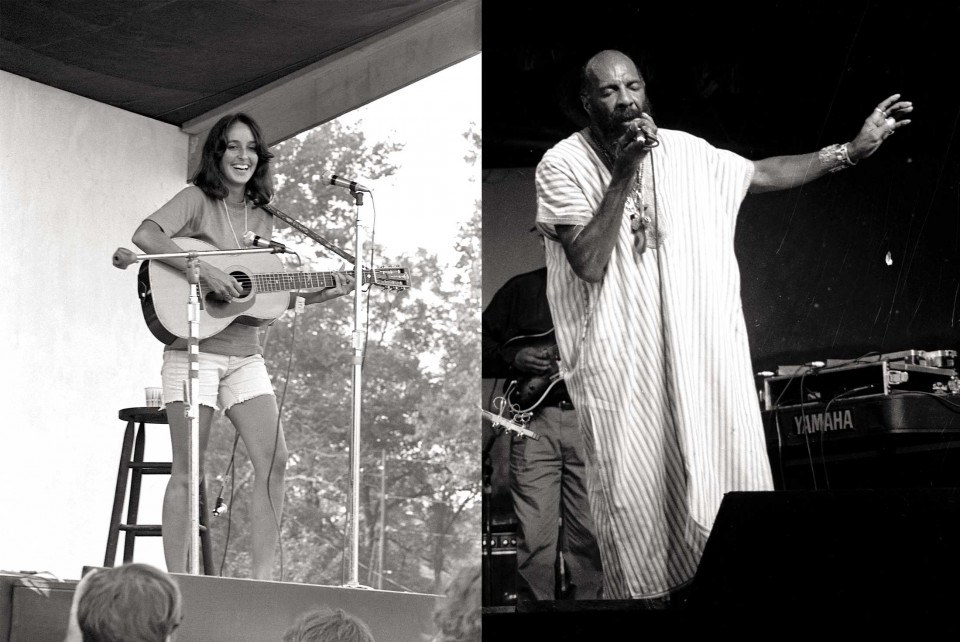

Joan Baez in 1968 (left) / Photograph by Harvey Silver/Getty Images; Richie Havens in 1991 / Photograph by Jayne Toohey

I was taken at that first Fest by a singer named Bonnie Dobson — the first woman to sing “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face” (later a hit for Roberta Flack) and “Morning Dew” (yeah, the Grateful Dead staple). Also noteworthy: the grizzled, blind blues-and-gospel singer/12-string slinger the Reverend Gary Davis, source for “If I Had My Way” (covered by Peter, Paul and Mary and the Grateful Dead as “Samson and Delilah”), and Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, saddle pal of Woody Guthrie and inspiration for Dylan. And topping that first bill? His Master’s Voice, Pete Seeger, who warmed up the damp, chilly night and the thousand shivering souls by rallying all to sing along with “Guantanamera” and “I Don’t Want Your Millions, Mister.” Seeger was so taken by the homey scene and the all-volunteer operation that he gave back his paycheck. The next summer, Seeger brought Newport Folk Festival producer George Wein down to check out our fest. Newport Folk had started earlier, in ’59, but later skipped a few summers — the reason PFF dares call itself “the oldest continually operating” outdoor fest in North America.

Though not in one location, obviously. After four years of growth, the festival was forced to relocate another 25 minutes from the city — first to the Spring Mountain ski area in Schwenksville for a year and then up the road to the Old Pool Farm. All I remember of Spring Mountain is a gangly Arlo Guthrie (Woody’s kid!) bounding unbilled out of the audience onto the humor workshop stage to introduce his laconic hippie folk self with a half-sung/half-spoken and totally true tale of getting busted by the fuzz in Rittenhouse Square for playing a children’s game — “The Ring Around the Rosie Rag,” precursor to “Alice’s Restaurant Massacree.” And for the rest of PFF history, we’ve been hanging out on parts of Abe Pool’s farm. He’s long gone, but with festival support, the property is still in the family.

While maybe not so much today, Philly’s folk fest long enjoyed a rep as a tour stop artists just had to make. A writer for the Americana music publication No Depression claimed it was “second only to Newport” in importance to the music scene. Those who enjoyed coming-out parties at the festival include iconic singer-songwriters Joni Mitchell, Emmylou Harris, Janis Ian and Bonnie Raitt; politically charged finger-pointers Phil Ochs, John Prine, and the Mitchell Trio (featuring a feisty young John Denver); and pickers from Doc Watson to Chris Thile to Philly’s own Mike “Slo-Mo” Brenner. Talent was first tended to by Penn folklore professor Kenneth Goldstein, and early in its run, the festival gave platforms to rediscovered acoustic blues elders Mississippi John Hurt, Sippie Wallace, and Elizabeth “Libba” Cotten. And it championed global treasures, including Ali Akbar Khan and Babatunde Olatunji.

Its importance to the shaping of music tastes here is undeniable. During my first 10 years at the Daily News, crazy me crammed in a weekend side gig hosting/programming a couple shows on WMMR, which was then a prog-rock station where the DJs were free to play almost anything they wanted, so long as it was “in good taste.” A lot of this radio crew — Ed Sciaky, Michael Tearson, David Dye — were, like me, Folk Festival regulars and disciples of the legendary laid-back folk DJ Gene Shay. All of that is why Philly radio listeners were often first in the nation to hear, embrace and celebrate folk-attuned artists like Bonnie Raitt, Jackson Browne, Fairport Convention, and our very own Jim Croce, not to mention some talents that never played PFF but sure could/should have — olde-English-ballad-inspired Jethro Tull, the roots-digging Grateful Dead, and that Dylan-emulating surrealist from Asbury Park named Springsteen. And let’s not ignore the Hooters — the folkiest pop-rock band to ever come out of Philadelphia.

For better or worse, our Folk Fest became as much a communal social gathering as a musical celebration. I first felt the tides shifting in 1970 — the summer after Woodstock. The Fest suddenly needed a trip-tent, and some attendees never left the campgrounds; the brown acid didn’t go particularly well with sea shanties and Delta blues. Even today, lots of camping Festers only cross over to the concert zone for the evening shows. It’s telling that Smiling Banjo, the coffee-table book recognizing a half-century of Fests, devotes about a third of its pages to a celebration of campsite communes and the convivial committees of volunteers who come early, work a bit, and party a lot.

The budgeting for our Folk Fest reflects this; it’s structured quite differently from, say, the Newport Folk Festival. “That festival can spend 60 percent of its budget on talent — in part because it’s heavily subsidized by local patrons of the arts,” says longtime PFF insider David Baskin. “In Philadelphia, our $900,000 festival will devote 15 percent of its budget to talent and spend the rest on building — and tearing down — the production, the camping facilities, and the volunteers.” It stands to reason that if the Folk Fest built more permanent infrastructure on the grounds, it could be run far more efficiently. But then the property would be taxed as “improved,” and its owners don’t want that, I’ve heard.

Through the decades, I’ve mostly been a Fest commuter. But in the late 1980s and early ’90s, I camped in a bottom-land site called Marty’s Meadows (named after security committee chief Marty Singleton) with my then-wife Abbe and barely teen daughter Hilary. And yeah, I came to love my extended family and the peaceful vibes at Fest. I even fearlessly drove up and dropped Hil off (I went back to town) so she could hang out and help my friends on the volunteers committee. Yup, there are so many volunteers that they need their own 60-member support group.

Campers get muddy in 1994 / Photograph by Jonathan Wilson

Clearly, not all is wonderful about this huge, insular, semi-functional festival family in terms of efficiency and attitude. With its core of 2,000 to 2,500 volunteers serving on 20-plus semi-autonomous committees, the Fest takes on a “bottom up” feel, with varied fiefdoms like grounds (an eight-week build-up-and-tear-down job), sanitation, food services and communication operating in their own domains. There’s a fair amount of power-brokering and land-grabbing in the camping grounds — so when paying campers show up later, they sometimes have to settle for fringe-field accommodations.

And can it really be financially healthy when almost half the people you see walking around the concert zone and hanging in the campsite are wearing badges? It was a different fiscal proposition in the first few decades, when the volunteers only represented 10 to 25 percent of the Festival population.

In this very socialized order, volunteers enjoy free admission to the shows, free camping and free food. And they can’t imagine having it any other way. A bunch howled in protest — some even stopped coming — when the bean counters finally decided (15 years ago) to impose a volunteers’ administration fee — originally $20, now up to $50 to $65, “but still just half of what it really costs us to keep them safe with food, water, Porta-Potties and liability insurance,” calculates Baskin, who came up with the idea.

On the other side of the coin, volunteers often sacrifice vacation time and contribute skilled labor for the love of Fest. And David Schena — former PFF governance chair and CFO of a Malvern-based tech company — argues that “when you let the volunteers in early and for free, they set up the site, ‘reserve’ extra tent spots, and then invite friends to come up and party. They’ve made the experience more attractive. So you wind up with 2.5 paid campers for every volunteer.”

Baskin says sales of the most profitable all-Fest-with-camping-tickets (on sale now for $235; $295 at the gate) have been sliding slowly since their peak in 1991: “That’s the year when we had the entire Seeger family onstage. We had 5,700 paid campers living on the grounds plus another 1,500 or so overnighting volunteers, and it was crazy-crowded.” Of late, he notes, that paid-camper number has dropped below 2,500: “We really need it to get back above 3,500 for the Fest to be profitable.”

Ever the “house” watcher and nose counter, I’ve stressed for years as the crowds have slowly dwindled on the Festival grounds, dropping from daily peak paid attendance of 12,000 to 14,000 in the “folk scare” (boom) years — from the late ’60s through the early ’90s — to maybe a third of that at recent gatherings. What else besides an unwelcoming campground might be bringing attendance down?

Once the only game in town — and such hot news that local TV stations would helicopter out to cover it — PFF now has to contend with dozens of summer music rivals, from the folky Bryn Mawr Twilight Concerts and King of Prussia’s Under the Stars series to multi-day events like the jammy Peach Music Festival (June 30th to July 3rd at the Pavillion at Montage Mountain, near Scranton), the Delaware Valley Bluegrass Festival (Labor Day weekend, September 2nd through 4th, at the Salem County Fairgrounds in New Jersey), and WXPN’s XPoNential fest on the Camden waterfront (September 16th through 18th). It’s especially telling that the Delaware Valley Bluegrass Festival has only lost significant money one (hurricane-fraught) year out of 50. Its setting has permanent structures — including a roofed/open-sided concert pavilion, a covered picnic zone and indoor plumbing — so the nonprofit fest can get up and running quickly with a volunteer staff numbering just 250.

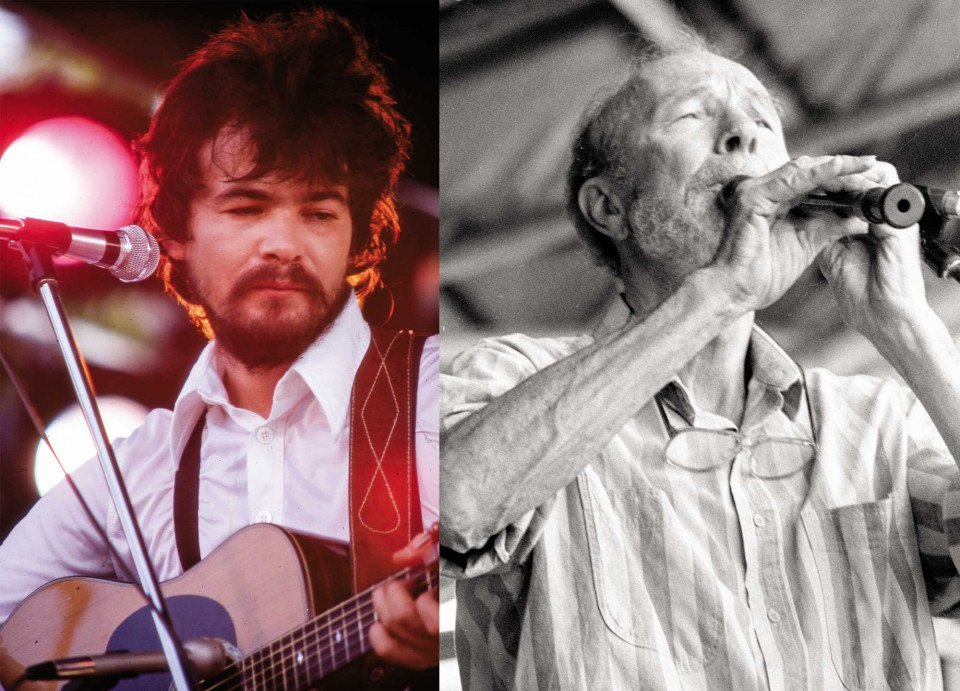

John Prine performs at the Fest in 1974 (left) / Photograph by Barry Sagotsky; Pete Seeger in 1991 / Photograph by Jayne Toohey

Artists who gratefully played Philly’s folk festival for modest fees as newbies — like Raitt and Browne — now make way more moolah as solo stars at summer sheds like the Mann (once off-limits to pop music!), “where they can play to 4,000 under cover and not worry about their guitar going out of tune,” bemoans Folk Festival programming director Lisa Schwartz. PFS and PFF have rarely exploited the Fest’s act-breaking ability by contractually locking in return engagements at larger, more profitable venues. (Two-at-once booking deals can also spark lower performance fees for each show.) To extend its reach, PFS opened a performance space in April 2018 as part of its new headquarters at 6156 Ridge Avenue. The Roxborough Venue (as it’s called) accommodates 135 listeners seated or 180 with floor and balcony attendees all standing, calculates PFS executive director Justin Nordell. True to populist PFS style, this all-ages, alcohol-free showcase normally charges just $10 to $20 for admission. But that’s not a formula for sustainability (let alone significant debt relief), argued several industry-savvy board members (all of whom have since resigned) when Nordell was pushing for the new clubhouse, modeled after the Old Town School of Folk in Chicago. By contrast, Old Town’s Szold Hall seats 170, but its Maurer Hall seats 425, making the latter big enough to attract established talents like Irish band Altan, Suzanne Vega and Valerie June. And both those venues offer snacks, beer and wine, so they’re major profit centers.

Making matters worse, the hills seem to have gotten steeper at the Old Pool Farm for some longtime visitors. And lots of second- and third-generation Festies who grew up camping there (including my own daughter) were never really that much into their parents’ music; they just liked the scene and lost interest after going off to college. It’s a pity that current crossover stars like Ed Sheeran and Billy Strings weren’t nabbed by Fest in their early gestation, since both are ginormous with the young-adult audience PFF so desperately needs to build a future. Bluegrass jammer Strings, ironically, is managed by a fella named Bill Orner — “a good friend who used to do graphics work for the Philadelphia Folk Festival,” brags Schwartz. So WTF happened there?

Philly Folk Fest prides itself on insular continuity — nurturing kids to join and eventually take over their elders’ volunteer leadership roles. The “keep it in the family” ideal is most boldly on display in the tenacious mother-and-son leadership team of Lisa Schwartz and Justin Nordell. She started attending and working at the Fest as a teen. He first went as a four-month-old infant: “Since my parents met at the festival, I wouldn’t even be here without it,” he says.

But learning to assemble badge holders and slap together sandwiches is different from negotiating for headliner acts who demand 50 grand (but might take 30) or steering a 501(c)(3) nonprofit with a budget that’s swelled from $1.3 million to $1.8 million.

Both Schwartz and Nordell are die-hard music fans, seriously ambitious, and blessed with the gift to emphasize positives and deflect (or bend) the negatives. Schwartz doesn’t even think it matters that the guy who took over Gene Shay’s folk show on WXPN, Ian Zolitor, hardly ever plugs PFS events — a “bad blood” breakdown yarn unto itself. “But who cares? He only has 150 listeners,” she snips. (Nielsen rates WXPN as having a 1.7 percent share of the radio listening audience from 6 a.m. to midnight, so 150 listeners is likely a major understatement.)

First the Folksong Society president and then the festival director, Schwartz had never negotiated artist contracts before also taking on the programming gig in 2017 — pushing out the experienced Point Entertainment team of Rich Kardon and Jesse Lundy. Her reason for canning those nine-year Folk Fest booking vets is curious. She told me Kardon “tried to sell the festival” to another concert promoter during a meeting at the Mann Center. Kardon replies (and a Mann source in attendance at the meeting confirms) that he was just proposing a “Folk Festival Presents” one-day event at the Mann to raise awareness and much-needed funding for the Old Pool Farm fest that is, let’s be real, a hell of a Lyft ride away from the city.

Nordell spent three years in the membership/education/community outreach department at the Philadelphia Film Society and two years fund-raising for the now-Philadelphia Ballet’s North Philly HQ project before winning the executive director job at the Folksong Society in 2015. (Then-PFS president Schwartz recused herself from the vote.) When Nordell is asked about a failed $1.2 million capital campaign he announced soon thereafter and then quickly abandoned — it was intended to pay for a new performance/education/office/archive space — he recalls “haranguing the 2015 Festival crowd mercilessly all weekend to give, really making a pest of myself. And we did get the most donations [in quantity] ever.” He then deflects: “It’s a good thing that [property purchase] didn’t work out, because the location we picked needed expensive remedial work, and we then connected with the Roxborough Development Corporation, which found us a very nice subsidized-rental property. So it all worked out well.”

“This business of [Kardon] being a traitor is from the old school of the Folksong Society, when people could be really nasty to each other,” says Baskin. ‘People were very protective of the Fest; everything was taken personally. It was childish. If you tried to do something differently, they thought it was a way to screw the Festival. Lisa saw that, grew up with that crowd.” As for the terrible notion of collaborating with commercial promoters? “I actually considered doing that, too, at one point,” he says. “Electric Factory Concerts’ Larry Magid and Allen Spivak were always considerate of the Fest, never programming competitive shows on our weekend.” (This year, by contrast, Fest must contend with a Brandi Carlile/Allison Russell/Celise bill on August 20th at the Mann. “There go 7,000 tickets,” grumbles Schwartz.)

Former PFS board member Mark Schultz quit over the firing of Point Entertainment. “As a lawyer, I began to get the feeling I was sitting on a board that was just an ornament,” he says. “Lisa and Justin were running the organization — would inform the board but frequently not even consult the board. When you sit on a board, you’re a fiduciary; you must have input, because you have a legal responsibility for the decisions. But these two were treating everything like it was a family business.”

As for lousy fund-raising, that’s a long-standing festival tradition, Baskin admits: “At one time, the organization had a million dollars in the bank but didn’t do anything with it. We didn’t invest in anything besides ongoing operations. And we didn’t build on our success by hustling for big donations — easier to get when you’re doing well — except when we built the Martin Stage [the festival site’s iconic main stage] 20 years ago. In most arts organizations, people contribute $5,000 to $10,000 to land a seat on the board, then are expected to go raise more. At PFS, the prime requisite is showing interest in the cause and the music. Lots of the board members have been musicians themselves. Some have even played at Fest. And given their social/political leanings, many have found it distasteful to go solicit money from big corporations.”

So just how bad off is PFS financially? It’s hard to say, since its accountants — recently changed — have yet to file IRS Form 990 (nonprofit organization) returns for 2020 or 2021. On its last posted IRS 990 for fiscal year 2019 — ending in March 2019 — the organization showed a loss of $386,595 and a remaining cash balance of $1,767.

Later that year, the PFS executive committee made a critical deal (not shared with the membership) to sell off its last piece of valuable real estate — the Wofford parking lot near the Fest site — for $240,00, to Upper Salford Township. This was ostensibly to pay back “zero percent” personal loans extended to PFS by two board members (who abstained from considering the property sale) and to cover losses accrued at the last live (2019) summer Fest, which climaxed with a fine — but costly — performance by David Crosby & Friends.

Dancing by the main stage in 2019 / Photograph by Jonathan Wilson

Nordell blames bad weather for poor walk-up that night and admits (unspecified) Fest losses. Schwartz spins it this way: “We doubled Sunday-night attendance from the year prior.” And, she contends, “I don’t think it was a factor” that Crosby played real good for free in Camden’s Cooper River Park 10 weeks before that Folk Fest.

Executive director Nordell is also slight with financials on the virtual 2020 and 2021 online festivals. He’d rather tout the “10,000 unique visitors” who watched part of the 2020 Fest “in 86 countries” — the global tune-in was swollen by large contingents of international acts (quite fine!) showcased by their national cultural-support agencies. The viewing number was “down by half” for 2021, he says, “because it was a smaller Fest, with fewer artists.” Nordell also defends the contracting of his software-programming brother-in-law Sam Bolenbaugh to build the Folk Fest’s online viewing site. “Sam was the only one we approached who was willing to give up everything else to jump on the project,” he says, “and as a Festival-goer himself designed the virtual site with great affinity for the actual event.” (I agree!)

Of the $869,254 that PFS scored in COVID relief funds in September 2021, the organization was still “sitting on a $300,000 war chest” as of March 2022, PFS board chairman Matt Diamondstone said then. But some of that money must be directed to ongoing operations of the busily booked Roxborough venue and to assorted music outreach programs. (PFS’s in-house early-childhood music appreciation classes and online musical instrument classes are “self-sustaining, 100 percent profitable,” says Nordell.)

Complicating the 2022 Festival’s recovery plans, 1,042 die-hard fans will be strolling through the gates this August with kicked-forward tickets purchased for the “live” 2020 Fest. We’re talking “about $185,000 in deferred revenue” here, David Schena calculates. These ticket holders can be added to the 2022 attendance count, but their money is already spent.

Perhaps there’s still hope for our Folk Fest. A whole lot is riding on the profit-building and cost-cutting moves being cooked up for the 60th festival by newly hired Midwood Entertainment — the first outside event managers the Fest has employed since then-PFS president Lisa Schwartz gave the boot to Michael Cloren (Fest director from 2011 to 2014), then claimed his job. (Three years later, Schwartz further consolidated when she claimed Point Entertainment’s programming duties, too.) A Charlotte, North Carolina-based event and venue management concern fronted by Micah Davidson, Midwood has established a good track record with roots-rock and blues-themed fests in the Southeast U.S. and is also taking on the first Americana-rock-themed White Rose Music Festival, coming to PeoplesBank Park in York on October 7th and 8th. After assessing our local situation, team ops have come up with a bunch of ideas to run the Philly fest more smoothly and profitably. But to be clear, they aren’t co-producers with shared financial responsibility, an arrangement that might have been more reassuring for our hard-suffering Fest and its parent organization. Such an arrangement might be threatening to some and challenging for a nonprofit to pull off.

One of Davidson’s first moves was to hire Lisa Schwartz (!) to book the festival, shortly after she resigned her “unpaid” position doing the same job for PFS. (She claimed she’d “had it with the crazies” criticizing her on the unofficial Philly Folk Fest Facebook group and even moved away from the region “because I was getting death threats.”) So how did her whiplash-quick comeback happen? Schwartz says, “I knew Micah from music-industry events.” (She’s now president emeritus of Folk Alliance International.) “He called me to say he’d applied for the project and needed a booker who ‘knew the territory.’” Not incidentally, Schwartz has been working on the talent lineup for another prestigious event, the English countryside Cambridge Folk Festival (July 28th through 31st), “which, at age 57, is going through the same issues as Philadelphia,” she says.

This year, for a change, the biggest and loudest performances at PFF will alternate between two stages — Martin and Camp — well into the evening hours, just as we see at the semi-competing (for talent/attendees) XPoNential Festival in Camden. In years past, Camp stage shows competed for attention, and sometimes clashed sonically, with shows happening on smaller stages near the Martin main stage. This change in Folk Fest flow-charting should result in clean sound, shorter lag times between acts, significantly longer sets, and fewer artists on the weekend’s talent payroll, which in recent years has loomed around the $300,000 mark.

For older citizens concerned with the dirt-and-gravel trail between the stages, Fest will beef up its golf-cart taxi service. And from twilight on, you should be able to stay put by the Martin stage and watch the last Camp performers on large projection TV screens. That’s good news for my “new knees and old hip”-challenged camping buddy, Barry Wilen, who’s coming back “for the first time in years” for a couples reunion attuned to the big 6-0.

While Midwood evidently suggested other production cuts, only one of the festival’s eight prior-year stages (yes, there have traditionally been eight stages) is being fully eliminated — the Front Porch Stage in the campgrounds.

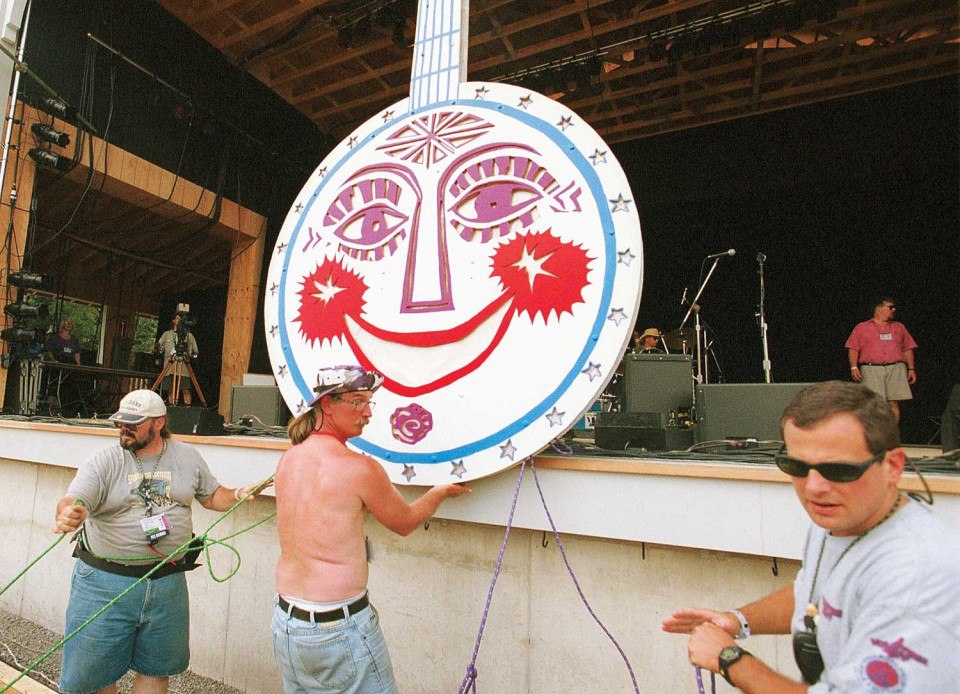

Installing the smiling banjo sign at the Martin Stage in 2001 / Photograph by Jonathan Wilson

To shake loose more cash and liven up the party, Midwood has nudged the Fest to open a second, tarp-shaded beer garden at the site — adjacent to the Camp stage — and broaden drink offerings with wine and hard cider options (subject to LCB approval). Party on! “They told us we were leaving money on the table,” says Nordell. “You may also see some discreet advertising signage at the site and more spots on the streaming version, but nothing obnoxious.”

Some backstage changes are also being plotted, including bringing in outside security professionals and restructuring how volunteer committees work so those in charge are required to rotate positions.

As for the talent at this year’s Fest, I’m not seeing any budget-busting “monster” acts — probably a good thing — though there’s many a talent that should surprise the crowd and get you shrieking.

Nostalgia will certainly have its place at the 60th commemoration — with throwback music perennials Jim Kweskin (lately into cute classics like “Lady Be Good” and “Makin’ Whoopee”), Happy Traum, Livingston Taylor and Tom Rush.

But aggressively looking forward — promoting artists who celebrate diversity and growth — seems a far bigger Festival theme, from the aforementioned reggae-tinged conscious-vibes spreader Michael Franti & Spearhead to the notable booking of Arrested Development — the purest personification of hip-hop to ever play this show. “Hip-hop and spoken word are as close to the original troubadours as you can get, IMHO, so totally folk music,” opines Schwartz. “Folk spaces are historically white spaces, and I’m hoping to do my part to change that a bit.”

Fortuitous new discoveries are also in the cards, especially in the rich, expanding domain of alt-country string bands — represented by roots-meets-conservatory crossovers Twisted Pine, Dustbowl Revival, the American Acoustic revue (Sarah Jarosz, Punch Brothers and Watchhouse), folk chanteuse Aiofe O’Donovan, and the hyper-fresh eight-piece Finnish “Nordgrass” ensemble called Figg. (They stole my heart at last year’s virtual Fest.)

Also sure to twist heads: cool-grooving singer/songwriter Hiss Golden Messenger (the one overt nod to WXPN land), retro-jazz-and-blues party band Davina & the Vagabonds, edgy Australian country export Catherine Britt, gospel-fired duo The War & Treaty, flashy piano man Matt Nakoa, and high-energy Celtic stompers Talisk. And take, please, the ear-opening South Korean folk roots revival troupe Al Dan Gwang Chil (ADGC), another head-expanding group that played last year’s virtual Fest and makes its live debut this year.

So yeah, it sure seems like there are some signs that the Fest is getting with the times. And maybe, with a bit of that outside professional input it has often bucked against, things might be turning around. Is it too little, too late? The best thing you can do is go. Or buy into the live and recorded stream. Or both. And please say “Hi.” We’ve got catching up to do, too. That yucky maroon t-shirt should make me easy to find.

Published as “Hanging On By a String” in the June 2022 issue of Philadelphia magazine.