How the Pandemic Brought Campbell’s Soup Back From the Brink

As a nation, we had moved on from Campbell’s. Then, last year, a bowl of Tomato and a grilled cheese sammy started sounding mighty comforting. Is this the beginning of a new chapter for Philadelphia’s favorite soup?

It’s a Campbell’s Soup world. Photo Illustration by Andre Rucker

Campbell’s Soup was in hot water. The venerable company, born just across the river from Philadelphia in the city of Camden, was due to celebrate its 150th anniversary in 2019. The trouble was, there wasn’t much to celebrate. Its stock price had dropped by 29 percent over two years. Much-touted CEO Denise Morrison — one of just 24 female leaders of Fortune 500 companies at the time — had abruptly retired (or been pressured to resign, depending on whom you asked). Younger consumers were shunning good ol’ Chicken Noodle and Vegetable Beef in favor of bowls of pho and ramen. Efforts to diversify the firm by moving into fresh foods had bombed; the quarterly report that provoked Morrison’s departure showed a $393 million loss and a tripling of Campbell’s debt burden, to $9.6 billion. The company had recently announced a “strategic reorganization” and a major review of its entire product line in what the New York Times described as “a deep identity crisis.”

M’m. M’m. Not good.

But never fear. The company, founded in 1869 by a small-time New Jersey purveyor of produce and preserves, was about to be saved by the most unlikely of redeemers: a global pandemic that would send consumers scurrying back to grilled cheese sandwiches and Campbell’s Tomato Soup en masse. After all, this wasn’t the first time world events had bowled the company over. You could even say Campbell’s has regularly landed, um, in the soup, only to ladle its way out again.

The first thing to know about Campbell’s founder Joseph Campbell is that he didn’t have much to do with the company that’s named for him. After he and his early partner, a tinsmith named Abraham Anderson who was enamored of the new fad for preserving food in cans, snagged a medal for the quality of their goods at Philadelphia’s 1876 Centennial International Exhibition, Campbell bought out Anderson’s shares and acquired three new partners. The most vital of these was Arthur Dorrance, a wealthy merchant whose family had been in America for centuries. Their new enterprise, Joseph Campbell & Company, continued to focus on canned foods, consumption of which had accelerated following the Civil War. (The North had a large canning industry, which the South lacked, and Union soldiers had come to appreciate the tasty convenience of food scooped from a can rather than scavenged from fields and farms.) Dorrance brought into the company his nephew, John T. Dorrance, a chemist trained at MIT and in Europe who would reimagine the business through his promotion of what’s now considered the most mundane of foodstuffs: condensed soup, introduced by Campbell’s in 1897.

Chemist/ad genius John T. Dorrance.

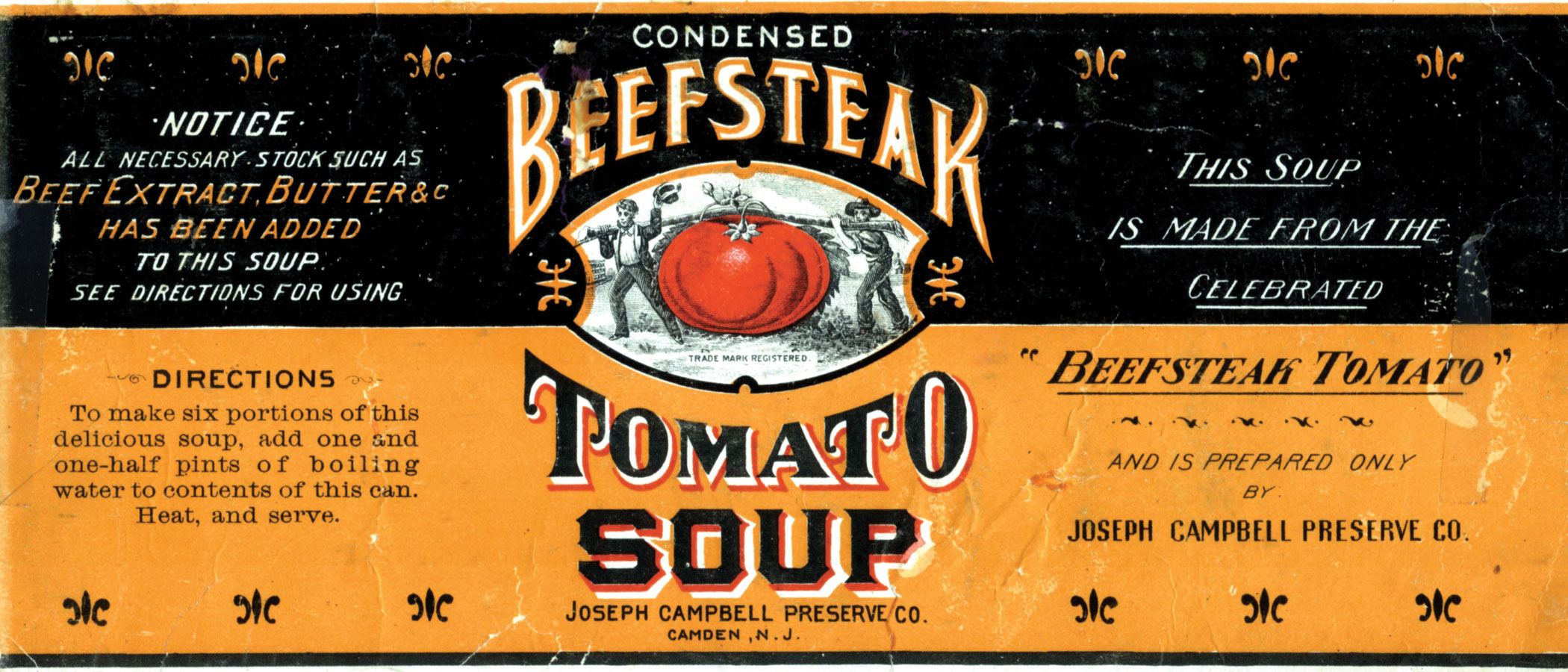

John T. wasn’t the first to condense food — a man named Gail Borden, horrified by the tale of the Donner Party’s turn to cannibalism, had invented canned condensed milk in 1853 to prevent any further such mishaps. Nor was Dorrance the first to can soup: The Franco-American and Huckins companies were already offering it to America, in half-pints, pints and quarts. But Dorrance did figure out that what made soup expensive to ship, and thus to sell, was the water it contained. Prepare it with less water, he realized, and those transport costs would go down. Joseph Campbell died in 1900, the same year his company’s soup won a bronze medal for product excellence at the Paris Exhibition — the medallion still featured on the cans. Now helmed by Uncle Arthur, the firm was soon turning a profit, selling its five original varieties — Tomato, Consommé, Vegetable, Chicken and Oxtail — for 10 cents a can, which was less than a third of what the competition charged. (Several different color prototypes for the label, including black and white and orange and black, were considered before the company treasurer, enchanted by the crisp look of the Cornell football team’s red and white jerseys at a game against Penn, suggested that combo.)

The 1897 label from Campbell’s first condensed soup.

Even more important than his chemistry genius, it would turn out, was John T. Dorrance’s marketing genius. This becomes apparent when you realize he had to generate desire for a product — canned soup — that hadn’t really existed before. Americans didn’t eat soup the way he’d encountered it in Europe — served as a separate first course at dinner or accompanied by a baguette and a nice Emmenthaler for le déjeuner. Nor were our native housewives accustomed to keeping a stockpot simmering on the stove. The United States was a meat-and-potatoes land.

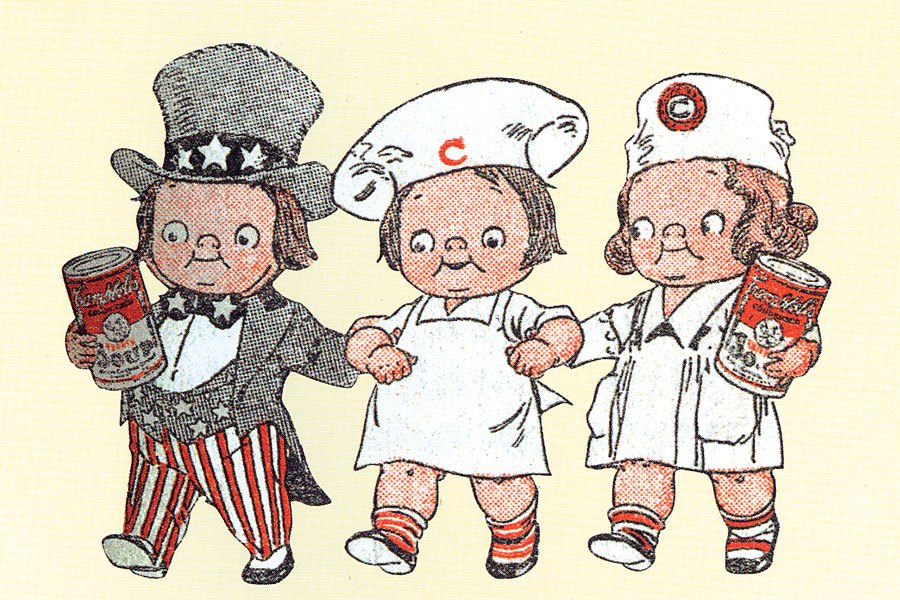

To familiarize the public with his product, Dorrance turned to a new form of advertising: placards mounted in city streetcars. A local car-card printer who was trying to drum up business asked his wife, Grace Wiederseim, a freelance illustrator who’d attended Drexel, to try her hand at creating some characters to illustrate these soup ads. (She’d later remarry and be known as Grace Drayton.) The ones she came up with — the Campbell Kids — would star in the company’s ads for most of the next century. By 1905, Campbell’s was selling 20 million cans of soup a year.

The Campbell Kids starred in company ads for most of a century.

Ads a century ago were different from the ones today. They were … bossier. More freewheeling. They promised more, much more. In a pre-vaccine era when contagious diseases — flu, yellow fever, measles, mumps — still regularly killed millions of people, health mattered. And the chubby, red-cheeked Campbell Kids proudly proclaimed it was soup that made them healthy and strong. Campbell’s ads sang the praises of the company’s highly “antiseptic” production facilities — so much more sanitary than your own kitchen, lady! They touted soup’s nutritional benefits (“helps to regulate the body-building processes of the entire system”) and ease of preparation. And as American women were gradually moving beyond traditional gender roles — called upon to serve in factories in wartime, struggling to fit into the larger world of business employment — Campbell’s shamelessly played on their guilt, assuring them that with the help of its soups, they could still fulfill their wifely and motherly duties. (“And only one maid! How do you manage so nicely?” a well-dressed luncheon guest asks of her hostess in a 1912 company ad.) “That’s where his genius lay,” Rosemary Trout, program director of Drexel University’s Culinary Arts & Food Science program, says of John T. Dorrance. “He was able to do that so effectively.”

“Campbell’s ads sought to persuade women not only to buy their products,” writes Katherine Parkin, “but also to buy their vision of how women ought to work and live”

At least one part of the Campbell Kids pitch was realistic: Canned soup served to diversify the American diet when people really did eat locally — because they had to. “Canned food is pretty fantastic when you think about it,” Trout notes. “People could get highly accessible nutrient-rich food year-round, and it lasted a long time.” It may be fashionable right now to “think local,” she says, but there are limits to that: “You’d have no coffee, no chocolate, no pineapple.” She’s a big admirer of Campbell’s, which has long had a relationship with Drexel’s culinary arts program, places co-op students in its test kitchens, and regularly hires alumni as well.

There’s one more Drexel connection to Campbell’s that can’t be overlooked: It was a Drexel grad, Dorcas Reilly, Class of 1947, who invented Green Bean Casserole, the staple of the holiday table that turns 66 this year. Reilly was just eight years out of school and working in Campbell’s test kitchens when she first mixed cooked green beans with Cream of Mushroom Soup and topped them with crunchy canned fried onions. Campbell’s says the dish is now served in 20 million American homes each Thanksgiving.

Within five years of his introduction of condensed soup, John T. Dorrance had expanded the line to 21 kinds, adding Asparagus, Beef, Bouillon, Celery, Chicken Gumbo, Clam Bouillon, Clam Chowder, Julienne, Mock Turtle, Mulligatawny, Mutton, Pea, Pepper Pot, Printanier, Tomato Okra and Vermicelli Tomato to the original five. He was a stickler for quality ingredients and chose his varieties with an eye to sophisticated Continental tastes. In 1915, he bought out his uncle Arthur and became the sole owner of the Joseph Campbell Company.

Dorrance’s next advertising frontier was the world of women’s magazines. In 1911, Philly’s own Curtis Publishing Company, whose periodicals included the wildly popular Ladies’ Home Journal and Saturday Evening Post, had hired a former schoolteacher to figure out which products advertised in its pages were actually bought and used by consumers — one of the world’s first jabs at market research. The schoolteacher convinced dozens of local subscribers to let him root through their trash, which is how he discovered just how popular Campbell’s Soup was proving to be. What’s more, that popularity ranged across classes, prompting Dorrance to expand his advertising reach. By 1920, he was spending a million dollars a year on ads. He also teamed up with magazine editors to feature his products in the recipes they provided to eager readers, encouraging them to stretch their culinary repertoires by using soups as building blocks to glamorous dishes like Spaghetti à la Campbell (pasta was then viewed as an exotic food enjoyed by Italian immigrants) and Tomato Soup Cake. He published recipe pamphlets and menu books. He eventually acquired rival Franco-American. He funded copious research into tomato breeding. He introduced a new product, Pork & Beans, to keep his Camden plant humming during the days each week when his soup stocks were simmering. That soup was still the company’s backbone, as shown by a 1921 name change to the Campbell Soup Company. By the time of John Dorrance’s death in 1930, he was worth some $115 million and was the third richest man in the United States.

His life, in short, was a capitalist triumph. Not everyone, though, is a wholehearted capitalist. In a chapter on Campbell’s in the 2000 book Kitchen Culture in America, published by the University of Pennsylvania Press, food historian Katherine J. Parkin writes of the company, “Regardless of an ad’s tone, cajoling or foreboding, it always carried the same implied threat: not using Campbell’s soups would result in some type of failure. Their ads sought to exploit women’s doubts and anxieties.” Those doubts and anxieties only grew as the 1950s and ’60s brought increased societal upheaval and even greater changes in gender roles. The male Campbell Kid was a child of action — boxing, soldiering, piloting a plane — while his female counterpart eyed him adoringly, hung laundry, and served his meals. As Parkin notes, “Campbell’s soup ads exploited traditional gender ideals to persuade girls and women not only to buy their products but also to buy their vision of how women ought to work and live.” In the same breath, though, ads emphasized how all-consuming cooking was and how liberating canned soups were, promising they “save your time for other things.”

In the end, even an ocean of Campbell’s Tomato wasn’t enough to hold back the tide of history. The decades following World War II proved to be canned soup’s heyday, with a million Campbell’s cookbooks in print — titles included Cooking with Condensed Soups and Wonderful Ways with Soups. (Campbell’s Cream of Mushroom was so ubiquitous in church cookbooks in Minnesota that it was known as “the Lutheran binder.”) But by the 1970s, soups were starting to struggle. Housewives who in earlier eras delighted in one-dish meals and casseroles were giving way to a new generation that preferred lighter, fresher foods, like grilled plates and salads. Campbell’s experiments with fruit soups (!), frozen soups, and salad dressings made from soup didn’t go anywhere. Andy Warhol’s iconolatry of the familiar red-and-white can — though he insisted he loved Campbell’s Tomato Soup and ate it every day as a child — made the products seem quaint and even faintly ridiculous in the era of nouvelle cuisine. America was embracing the foods of other cultures — and simultaneously, oddly, returning to the yen for local, as embodied in farmers’ markets and CSAs. The company’s 21-product line had long since been overhauled and diversified — today, the Campbell’s website lists 70-some varieties of soup in those red-and-white cans, including Chicken Wonton, 98% Fat-Free Cream of Mushroom, and Cream of Cremini & Shiitake Mushroom (not to mention other lines, like the Chunky soups that former Eagles QB Donovan McNabb and his mom repped). A company that had built its growth on backward-facing nostalgia — its TV advertising leaned toward Lassie, The Donna Reed Show and The Mickey Mouse Club — was suddenly confronted with Gloria Steinem and the ERA.

Campbell’s had already been expanding, acquiring C.A. Swanson & Sons, inventors of the TV dinner, in 1955 and the Pepperidge Farm bakery in 1961. Now it added more companies to its portfolio, including Godiva Chocolatier, Inc., Mrs. Paul’s frozen seafood and Vlasic pickles, and enlarged its operations overseas. Embracing the trend for foreign foods, the company put out a new cookbook, The International Cook, that employed its soups in dishes such as Middle Eastern bamia, Eastern European chikhirtma and German rinderrouladen.

Crates of soup waiting to be shipped out in 1910.

The turn of the century brought another challenge to the company’s dominance: Families who’d happily stirred up Heavenly Ham Bake and Perfect Tuna Casserole were suddenly paying more attention to health. The big bugbear with condensed soup was sodium, which research increasingly linked to heart disease and high blood pressure. Along with other major food producers, including Kraft and Heinz, Campbell’s in 2010 signed on to the National Salt Reduction Initiative, pledging to reformulate 60 percent of its canned-soup line to reduce salt content by as much as 45 percent.

Unfortunately, Rosemary Trout points out, salt is one of the reasons condensed soup works so well in sauces and casseroles: “You end up with a very concentrated, very saline solution. That enhances the flavor.” CEO Denise Morrison blamed the low-sodium soups for even further erosion of sales — and in 2011, after a paper in the Journal of Hypertension cast doubt on the link between sodium and heart disease, she announced a shake-up: The company was putting the salt back in.

Changing consumer tastes weren’t the only problem Campbell’s confronted in the closing decades of the 20th century. The company had always taken advantage of New Jersey’s agricultural wealth — those harvests of ripe red tomatoes and glistening green peppers — in making its products. But supply chains were reconfiguring, and harvests could be had more cheaply now in California and the Midwest. Labor could be, too, according to Daniel Sidorick’s 2009 book Condensed Capitalism: Campbell Soup and the Pursuit of Cheap Production in the Twentieth Century. Under the Dorrances, Campbell’s was anti-Communist and anti-union. It relied on immigrant labor, hiring waves of new arrivals to America — Italians, Puerto Ricans, Jamaicans — provoking complaints from Camden old-timers that it was “ruining the city.” (Plus ça change … ) Managers would segregate Black and female workers into lower-paying jobs and relentlessly squeezed every last ounce of production from their employees. Finally, in 1990, Campbell’s shut down its last Camden plants in favor of operations elsewhere in the country (the corporate headquarters remain), prompting those same old-timers to gripe about their abandonment.

“Campbell’s is familiar to people,” says Rosemary Trout, of Drexel University’s culinary arts program. “We were all looking for some comfort, I guess.”

According to Sidorick, the closure of the Camden plants was just another extension of John Dorrance’s corporate philosophy of keeping production costs low. In other aspects, though, Campbell’s could be quite forward-thinking. A decade ago, it flirted with the possibility of Keurig soups. Its 2015 “Made for Real, Real Life” ad campaign made a splash by featuring two gay dads. (One Million Moms, an advocacy group that fights “indecency,” called for a boycott, naturally, accusing the company of “normalizing sin.”) In 2016, it became the first major food company to support federal legislation to provide transparency on the presence of genetically modified organisms, or GMOs, in what one public-health lawyer termed “a watershed moment” for groups opposed to their usage. That same year, it pledged to remove all artificial ingredients, including high-fructose corn syrup, from its products and introduced its Well Yes soups, in non-BPA-lined cans. It’s been repeatedly recognized as a “Best Corporate Citizen” by Corporate Responsibility Magazine. And in 2019, Campbell’s was one of only 20 American companies — and one of just two U.S. food companies — to appear on the Corporate Knights list of the Global 100 Most Sustainable Companies in the World.

None of that good behavior seemed to matter much to the company’s bottom line. That same year, Campbell’s announced it was selling salsa maker Garden Fresh Gourmet, acquired in 2015 at a cost of $232 million, plus a refrigerated-soup plant it had built for $80 million, for the low, low price of … $60 million. Ouch. Since 2016, the company has had to write off $1.4 billion worth of $2.14 billion in businesses it acquired under Denise Morrison’s leadership. Her sudden departure touched off an ugly struggle between John Dorrance’s descendants — many of them with names, like Strawbridge and Wister, that are familiar to any longtime Philadelphian — and Daniel S. Loeb, of Third Point hedge fund, for control of the board. (One of Third Point’s proposals: Modernize those red-and-white cans.) In a single quarter, earnings tanked by 50 percent. “A Family Feud,” a Wall Street Journal headline proclaimed, “Threatens Campbell’s Dynasty.”

In the end, Dan Loeb and John Dorrance’s successors reached détente. Third Point got two seats on a (slightly enlarged) board and a say in the choice of a new CEO, who turned out to be Mark Clouse, a veteran of Kraft, Pinnacle, and Mondelez International. Campbell’s sold off Bolthouse Farms, the last of the Campbell Fresh acquisitions championed by Morrison, which it bought in 2012 for $1.55 billion, for $510 million, in June of 2019.

And then, somewhere in a bat cave near Wuhan, a mutation occurred.

I’ve been a serious stan of Campbell’s Soup for longer than I can remember. I grew up on 1950s meatloaf topped with Campbell’s Tomato — and I still make it, dammit. No Hingston Thanksgiving is complete without Green Bean Casserole. (That’s not quite true. One year, I tried a from-scratch version without the soup. It sucked.) I’ve passed on to my son my taste for Campbell’s Vegetable, reconstituted with milk instead of water for a creamy, delicious bowl of goodness. And for the past four decades, I’ve spent the night before Christmas Eve in my kitchen, doggedly rolling 12 pounds of ground beef into my long-dead mom’s delectable Swedish (hah! As if!) Meatballs, sauced with 12 cans of Cream of Mushroom and undying love.

James Regan doesn’t really want to talk about the past, though.

James is amiable and handsome and has only recently been appointed Campbell’s director of external communications when I write him and ask for his help. I’d like to speak to company president Clouse, or to the president of meals and beverages, Chris Foley. I figure 40-some years of all those cans of Cream of Mushroom every Christmas ought to buy me access. James seems willing enough, at first. The more we talk and exchange emails, though, the less willing he becomes. “We’d really love to focus on recent history and what’s ahead for the company,” he writes.

But what intrigues me most about Campbell’s — what makes the company worth writing about to me — is how it somehow survived so many changes in the zeitgeist. How, like the two-faced god Janus, it managed to be looking forward even when you could have sworn it was looking back. John T. Dorrance shamelessly playing on the insecurities of Jazz Age housewives should have sent his company straight into oblivion. That it rode the casserole train for so long before hopping off should have tanked it, too. Instead, as though repeatedly saved by some Soup ex Machina — a Depression, a World War, the full-fledged entry of women into the workforce — the Campbell Kids have been the Comeback Kids, again and again.

Which is what I want to talk to the Campbell’s honchos about. Instead, James offers up Kim Fortunato, who, curiously, graduated from the same college that I did, in the very same year. We hit it off right away. But her job at Campbell’s is vice president of community affairs; she also heads the Campbell Soup Foundation, founded in 1958 and doing good ever since. Kim tells me all about the company’s just-wrapped-up 10-year Healthy Communities Initiative to address the obesity rate in Camden County, and a new five-year program aimed at improving school nutrition. She calls the company “an economic engine” for the city of Camden. She discusses a partnership program with the Food Trust that helps corner stores in Camden provide fresh produce and consumer education. She shares that her favorite Campbell’s variety as a child was Vegetarian Vegetable. She even — finally! — acknowledges that the pandemic was good for business. “We’ve gained new households,” she says, adding that millennials are “a generation that didn’t cook as much. Now, with the pandemic, you have so many people cooking more. A lot of our soups can be used as an ingredient.” Yes! That’s what I wanted somebody at Campbell’s to say. It’s what the annual reports James keeps sending me show: Campbell’s U.S. soup sales rose by 15.3 percent in fiscal year 2020 — double the increase of any of the company’s other “edible categories.” In a single four-week stretch in the spring of 2020, sales of Campbell’s Soup shot up 59.3 percent year over year.

A Camden school kid at one of the company’s nutrition programs.

When people get scared, they want soup.

You can understand why Kim and James don’t want to dwell on this. It makes soup seem a little like guns — sales of which also spiked with the dawn of COVID — or maybe ivermectin, that horse de-wormer that anti-vaxxers keep slurping down. James would much rather talk about the performance of the company’s most recent acquisition, Snyder’s-Lance, Inc., makers of (coincidentally) my family’s favorite pretzels, not to mention all those little packets of cracker sandwiches. It’s like he wants to wrench both of Janus’s heads firmly face-front. But the pandemic is just the most recent disaster Campbell’s has persevered through.

What really gets me thinking about all this is a PR photo I see in September accompanying a press release about a food bank that Neumann University, in Delco, just opened “to alleviate food insecurity among its students.” In the photo, Rina Keller, a professor of social work, and Mary Beth Davis, a school counselor, stand in front of a veritable wall of … cans of Campbell’s Soup. There’s Chicken Noodle. Cream of Mushroom. Homestyle Chicken Noodle. Cream of Chicken …

Really? I think. I read that young people stopped eating cereal because it was so much trouble to wash out the bowls!

Well. Everybody did start making all that sourdough bread.

And then I think of something Drexel’s Rosemary Trout told me about the dark days of COVID: “Campbell’s is familiar to people. We were all looking for some comfort, I guess.”

“Campbell’s is intent on taking the momentum generated by its newfound fans and growing going forward,” says James Regan, Campbell’s director of external communications.

Curious, I decide to ask my junior magazine co-workers if they have Campbell’s Soup in their cupboards. These are the young folk, mind you, who snicker at me when I ask them what Smashburgers are or why anyone would want one, and who when we were still working in the office ate takeout lunches unfamiliar to me — larb, carnitas, gado-gado — every day. Younger generations are lethally cold about boomers, convinced that we connived to create climate change and have millions of dollars secretly stashed away in our ginormous homes. They want us all, frankly, to die.

“Two Cream of Mushroom,” says Gen X Victor.

“Six,” says Gen X/Millennial Cusp-er Kristen.

“Three Chicken Noodle and four Low-Salt Vegetable,” says the Other Sandy.

“One Tomato and three Paw Patrol Chicken Noodle,” says Kate, Mother of Two.

“Three! Tomato, Healthy Request Tomato and Chicken Noodle,” says Gen Z Shaunice, who’s even younger than my kids.

“One Tomato,” says Gen X Brian. “We usually have a couple of cans of Cream of Mushroom to make tuna noodle casserole, but we just made that, so we don’t.”

My God. Young people are still making Perfect Tuna Casserole?

I’m astonished. I’m bewildered. I sit at my desk (well, at my kitchen table), and for the longest time, I try to think of any other food item — bread? Ice cream? Milk? Coffee? Ketchup? — where so many different people, of so many different ages and backgrounds, would have the same brand on hand. None comes to mind. Campbell’s Soup truly is the universal food, America’s Soylent Green.

In July, with great fanfare, the Campbell Soup Company announced the first redesign of its iconic label in half a century. Traditionalists shuddered at the news, but when the updated cans were unveiled, they didn’t look … all that different. The Campbell’s logo, supposedly based on Joseph Campbell’s real signature, lost its backdrop shadow, and the letters were separated slightly. There’s a new font for the word “soup,” and little sketches of key ingredients — mushrooms, noodles, a tomato — beside the variety names. But the bronze medallion from the Paris Exposition is still there. The new design, the company says, “evokes the same sense of comfort, goodness and Americana.” To celebrate, Campbell’s enlisted street-style artist Sophia Chang to create its first-ever non-fungible token, or NFT, and auctioned it off to benefit charity.

Of course it did.

If I hadn’t read about the label redesign, I might not even have noticed it the next time I stood in front of the soup wall at Giant to restock my cupboard. As usual, Campbell’s was tweaking rather than revolutionizing, nudging the American consumer forward incrementally, just as it had when it introduced us to curry-flavored Mulligatawny and Victorian-era Mock Turtle, or convinced us to eat all those green beans and Tomato Soup Cake. After all, this is the company of which Fortune magazine wrote, way back in 1935, that taking the water out of its products was “the only basic idea anyone in the Campbell Soup Co. ever had.”

Now, James Regan tells me, the company is intent on taking the momentum generated by its newfound fans and growing going forward. In his remarks during September’s earnings call, Clouse noted the company’s recent soup success and added, “With COVID resurgence, I think some of the consumer dynamics that supported demand [are] likely going to be with us for a while longer.” In its report on the call, Food Dive, a website providing news for food industry execs, cited “home-centric eating behaviors” that are likely to continue as the impetus for soup’s resurrection: “The pandemic has helped revive and drive a reinvention of the category — one that could have staying power through the months and years ahead.”

Like most businesses at the moment, the company has been ironing out some pandemic-prompted supply-chain issues. Its ready-to-serve soups, including the Pacific Foods organic line, are showing signs of strength. The Well Yes soups were just reformulated to include trendy ingredients like bone broth and chickpeas. New “Snacking Soups” feature stir-in crunchies like oyster crackers and Pepperidge Farm’s beloved Goldfish. Those Snyder’s-Lance snack foods, by the way, are still going great guns. In that earnings call, Clouse cited particularly the brand’s inroads with … millennials. And he recently told the Wall Street Journal, “This is a moment where we should be treating some of these categories that have been around for 100-plus years like a new product launch.”

Everything old is new again. What’s cool about America, I guess, is that sometimes, all it takes is one basic idea, a little luck, and a hell of a lot of branding to cook up a dynasty.