How True Is Philly’s History? A Bella Vista Art Exhibit Asks the Question

Former Temple architecture professor John James Pron, who has an exhibition at the Da Vinci Art Alliance on display through September 13th, discusses Philly's (a)history, historical preservation and why he hates all public statues.

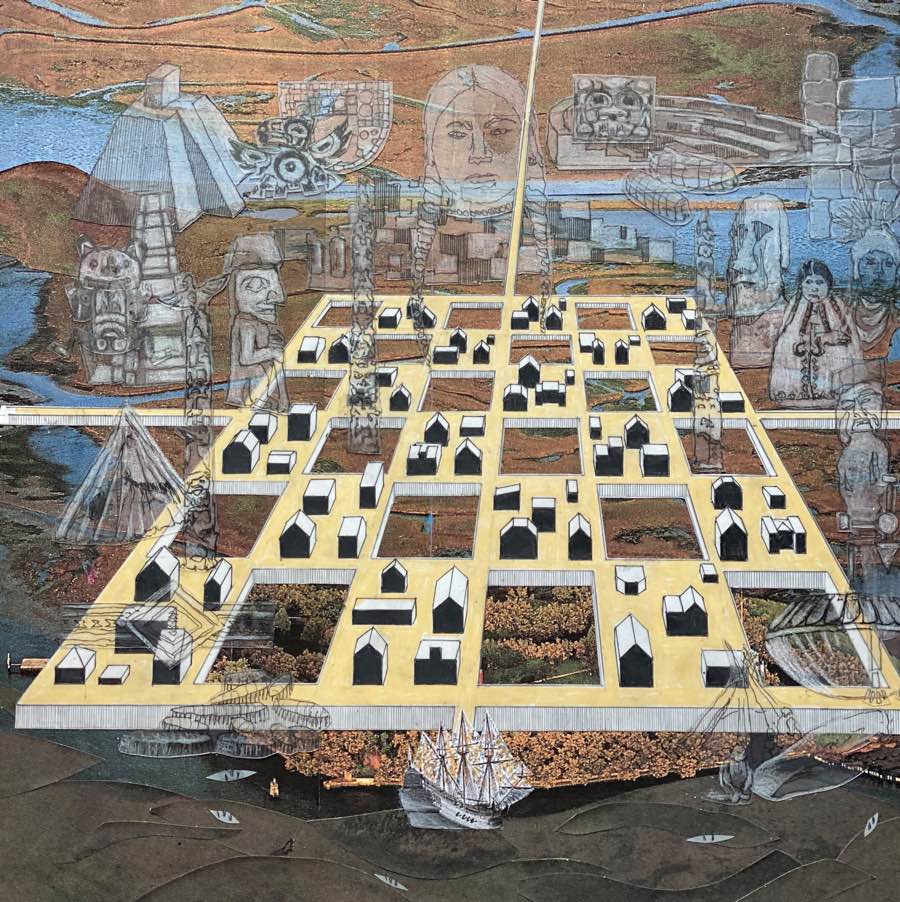

John James Pron’s “Philadelphia Fabulist” is on display at the Da Vinci Art Alliance through September 13th. Photos courtesy Da Vinci Art Alliance.

There is something about living in world-historical times that leads one to reflect on history. Maybe it’s the search for historical echoes. Or maybe it’s simply that we know this moment is soon to be rendered into historical narrative of its own. Which means it’s as good a time as any to do some thinking about how we’ve previously thought about our history — or, in many cases, ahistory — before.

This is one of the central themes of John James Pron’s “Philadelphia Fabulist,” an exhibition on display at the Da Vinci Art Alliance in Bella Vista. In the exhibition, Pron, a former Temple professor of architecture, has produced a series of drawings rendered as Philadelphia “fables.” In some, he casts doubt on classic Philadelphia stories, like that of William Penn as the benevolent city planner; in others, he makes up entirely new fables of his own (including a faux-Rocky origin story that is too convoluted and bizarre to explain here). Pron does not seem interested in earning your trust as an authority; if anything, he wants you to question him. And history more generally.

We caught up with Pron over the phone to talk more about the exhibit (on display, by appointment, through September 13th), historical preservation, and why he hates all public statues.

The exhibit is designed as a book of Philadelphia fables. Have you always thought of Philadelphia history in this way, or is there something about living in our current moment that has made you reconceptualize?

Well, I’ve retired from teaching, but I’ve been at Temple for about 40 years, teaching architectural history. And I’m a Philadelphian. There are lots of aspects about Philadelphia’s history that have always fascinated me, knowing that what we assume is true is not really true. So, the tower of Independence Hall, where the bell was hung — that tower was not there in 1776. It was a different tower that was torn down. The thing that was put there 50 years later, we love it as a symbol of freedom, but in fact, George Washington wouldn’t have recognized it. Betsy Ross, as far as we can tell, is a complete fantasy. There’s no evidence that she ever had anything to do with making a flag for George Washington. Our “history,” and I want to put it in quotes, is very different from the reality.

Do these kinds of stories have utility insofar as they create a shared narrative for Philadelphia? Or are they all just warping history to fit modern ends, and therefore worthless?

They are not worthless at all. I think they are important and valuable to help build a nation that was certainly unique in world history — people governing themselves. So I think they are positive and important. But I think we need to recognize that they are stories and not necessarily the truth. Christopher Columbus is a great example of that. So yes, they’re valuable. But it’s also valuable to accept the addendum of “history” in quotes. Things evolve.

Pron’s depiction of William Penn’s not-so-greene country towne.

Do you see a distinction between fable and history, or are these one in the same?

Fables teach morals. Aesop teaches you about the hare and the tortoise and all that. They have traditionally been for children to learn behaviors and learn respect. I don’t think this exhibit is really for children, and I’m kind of reluctant to kind of preach to adults in today’s world as if anyone is an expert. But I do want a healthy skepticism about what people consider immutable history. Even the statues. I want people to just be able to take a closer look, and look at the sources — who put this up, who said this. I’ve kind of pushed the boundary with a couple things, like with the Rocky [story]. Can you trust me, just because I am a university professor? Or should you not be skeptical? Look and check your sources, look at multiple sources and think through for yourself. I’m not about to preach or put out a moral. You’ve got to decide that for yourself in this complicated world.

A number of the questions you’re raising in the exhibit are the same ones surrounding the statue discourse, say, for Columbus or Frank Rizzo. You have a work called “Public Statuary Quarantine Station,” and in an explanation attached to that, you wrote, “I hate statues.” Tell me why.

I’m really talking about representations of human beings, or horse equestrian statues. I’m not talking about artworks that go to museums. But I think that monumental public statues are really archaic. I don’t think they help anybody to remember much about the past. A statue is a one liner. There’s one face, there’s one gesture, there’s one expression. The hand is held high, the Native American bends low. It’s like a one liner, whether it’s Columbus, or Rizzo, or anybody else.

Pron’s “Public Statuary Quarantine Station.”

Is it a statue-specific hate? I’m curious what you think of the Rizzo mural, for instance.

It’s standing in a public zone, the Rizzo mural, right?

Right.

And it’s right off of Ninth Street. I don’t have the same negative feelings about the Rizzo mural because that is his local community, a lot of people still revere him, and I feel bad that it gets vandalized by people outside of that community. I think that should be respected. But putting the statue of Rizzo in front of the Municipal Services Building, that is a public building. That’s the building that belongs to all Philadelphians. To me it’s offensive that it’s right in front of the front door. It’s too sectarian to occupy that important public position. I don’t know whether he’s waving, or holding his hand to keep people away. [The city removed the statue in June, and Mural Arts painted over the mural a few days later.]

The exhibit is making the point that history is not as static as we think it is, and that it should be changing. As an architect, does that color your approach to buildings? There’s a lot of discussion in Philadelphia about tearing down historic buildings, or not. Where do you come down on that question?

I think this is a city of many wonderful museums, and great character, and I wouldn’t want to see those compromised. But on the other hand, every building cannot be saved. Everything cannot be historic, unfortunately. Some things are very important to preserve as they are, like Auschwitz, like Independence Hall. City Hall, in the 1950s, I remember, was to be demolished, only keeping the William Penn tower in the center, making it into a traffic circle, because everybody thought it was the ugliest building and hated it. The only reason it was saved — it had nothing to do with its history or aesthetics or function. It was too expensive to knock down all that stone. So we kept it.

But parts of the city, like Old City, are really more wonderful because there’s the mix of new and old, and big and small. Some things have to go, and a new world has to be allowed to emerge as well. So I like the idea of new and old. That’s kind of what my drawings are. I have old black-and-white photographs, but then I render new things into it. So it’s not entirely a new picture, a new drawing, or an old drawing. It’s a blend of both. And I like that about cities. I like that about communities. I like that about our nation.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. It has also been updated to note that the Da Vinci Art Alliance is located in Bella Vista, not Queen Village.