10 Things You Might Not Know About Philly’s June 1919 Anarchist Bombings

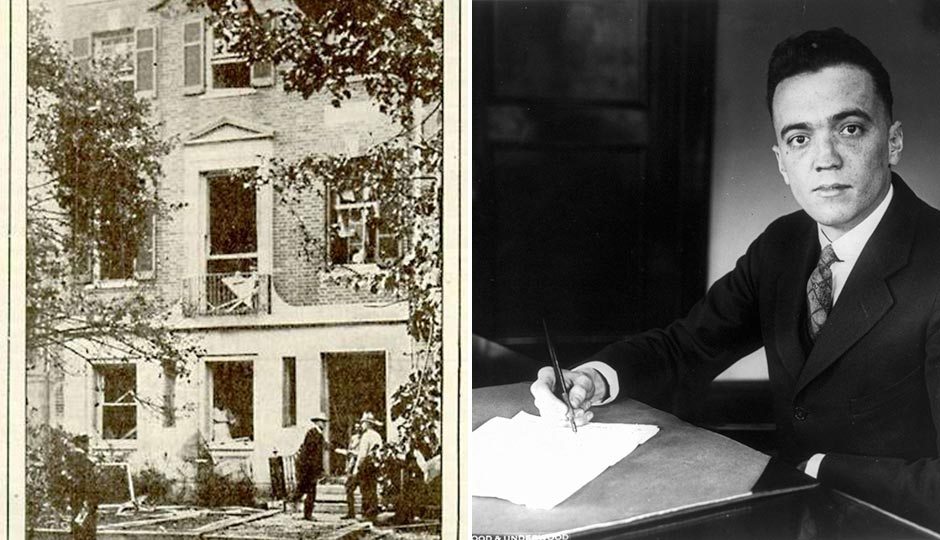

Left: Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer’s house with bomb damage. Right: a young J. Edgar Hoover

The Supreme Court’s recent ruling blocking President Obama‘s executive actions on immigration. A terrible hate crime against a club full of mostly Latino gays in Orlando. Foreigners blamed for violence and murder. Donald Trump‘s calls for a wall with Mexico. It’s hard to believe America has ever been more divided over whom to let into the country and whom to keep out — or deport. But there’s nothing new about cries of “America First.” On June 2, 1919, within 90 minutes of each another, eight bombs of what the FBI called “extraordinary capacity” exploded in seven U.S. cities: New York, Boston, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Patterson, N.J., Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia. The bombs, each constructed of as much as 25 pounds of dynamite and salted with heavy metal slugs meant to act as shrapnel, were the work of anarchists, according to fliers printed on pink paper. The frantic search for the bombers, centered in Philadelphia, would jump-start the career of future FBI director J. Edgar Hoover and lead to mass deportations of undocumented immigrants — with some unexpected consequences. Here, 10 things you might not know about those dangerous days.

1. Around midnight on June 2nd, two bombs blew up under the porch of the rectory at Our Lady of Victory Catholic church at 54th and Vine streets. At about the same time, another bomb exploded at the home of jeweler Louis Jajieky at 57th and Locust, leaving just the four outer walls standing.

2. Another bomb in the synchronized series exploded at the Washington, D.C., home of U.S. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer. That bomber, Carlo Valdinoci, apparently tripped while carrying the weapon to the porch, and it killed him when it went off. Palmer’s home was nearly demolished. Barely escaping the explosion were his across-the-street neighbors, Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, who had just walked past the Palmer residence; one of Valdinoci’s legs landed on their front stoop.

3. The only other casualty of the June 2nd blasts was a New York City night watchman, William Boehner. The bombs were addressed to government officials who advocated deportation of immigrants associated with anarchism and judges who’d sentenced such immigrants to prison. The fliers that accompanied them were signed by “The Anarchist Fighters” and read:

War, Class war, and you were the first to wage it under the cover of the powerful institutions you call order, in the darkness of your laws. There will have to be bloodshed; we will not dodge; there will have to be murder; we will kill, because it is necessary; there will have to be destruction; we will destroy to rid the world of your tyrannical institutions.

4. The June bombing was actually the second intended for the Palmer house. In April, 36 booby-trapped bombs set to explode on May Day — the international day of Communist, anarchist and Socialist solidarity — had been mailed to Palmer and other politicians and appointees, wrapped in paper and stamped “Gimbel Brothers — Novelty Samples.” The bombs were rigged with sulfuric acid that would eat through the blasting caps and then set off dynamite. An aide to the mayor of Seattle opened one of the bombs from the wrong end, and it failed to go off; he notified police, who informed the post office. An alert employee there had already intercepted 16 identical packages because they carried insufficient postage; another 12 bombs were later located and didn’t explode. But the housekeeper for a senator from Georgia lost both her hands when she opened one bomb.

5. The fliers that accompanied the June bombs were traced to a New York City print shop run by two anarchist followers of Luigi Galleani, an Italian immigrant who advocated resisting authority by violent means, if necessary. He was also the author of a book on how to make bombs. One of the printers, Andrea Salsedo, killed himself or was murdered by Bureau of Investigation agents, depending on whom you believe, and the other, Roberto Elia, refused to testify about the Galleanist organization and was deported.

6. A train ticket found on the dead bomber, Valdinoci, showed he’d boarded a train to Washington at 24th and Chestnut streets in Philly, and his hat label showed it had come from DeLucca Brothers hatters at 919 South 8th Street. The three DeLucca brothers who ran the shop told federal investigators they’d sold many of those hats, but that the bomber’s had to have been purchased at least a month beforehand, seeing as they’d since switched over to straw hats for the summer.

7. Those clues led the feds to center their investigation in Philly. Special Agent Todd Daniel, who headed the effort, declared that “the terrorist movement is national in scope, and it is not impossible that its headquarters is located in this city.” He also cited the many anarchists in the city and “so many places used by them for meeting places.” The feds began to put suspected anarchists, including members of the Industrial Workers of the World, under surveillance. Another bomb was found at the Frankford Arsenal on June 8th, but local police and the federal Bureau of Investigation were unable to trace it to the Galleanists.

8. Police had an eyewitness who saw four men driving away from Our Lady of Victory around the time of the explosions, in a car that had been reported stolen earlier that day from 12th Street and Columbia Avenue (now Cecil B. Moore Avenue) in North Philly. The car was later found abandoned in Fairmount Park.

9. By August 1919, the Department of Justice had set up a Division of Intelligence to work with the Bureau of Investigation on finding the bombers. This new division was headed by an ambitious young attorney, J. Edgar Hoover, who set to work gathering and disseminating intelligence information about the anarchists while warning the public to expect assassinations, more bombings and labor unrest. Federal, state and local police all worked together under Hoover to identify and round up anarchists in what became known as “Palmer Raids,” after the U.S. Attorney General whose home had twice been bombed. Some 10,000 people were arrested; 3,500 were detained, and 556 were eventually deported. The Palmer Raids were marked by overblown warnings about a worldwide communist revolution, illegal searches and seizures, warrantless arrests and illegal detentions. U.S. Secretary of Labor Louis Freeland Post, who considered the raids to be witch hunts, dismissed most of the cases.

10. Hoover’s agents warned of an attempt to overthrow the U.S. government, to fall on May Day 1920. When the date passed without incident, newspapers mocked Palmer’s fears and called on him to stop needlessly frightening the public. The “Red Scare” quickly died down as sympathies turned toward the illegal detainees and deportees, and the Justice Department was condemned for the “utterly illegal acts committed by those charged with the highest duty of enforcing the laws.” Palmer’s political ambitions were squelched, but Hoover went on to head the Bureau of Investigation for decades, rooting out Commies, denying the existence of the Mafia, amassing secret reports on Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders, directing the FBI investigation into the Kennedy assassination, and, after his death in 1972, being eulogized by President Richard M. Nixon. The June bombings have never been solved.

Follow @SandyHingston on Twitter.