20 Years of Covering Philadelphia Public Education, For Better and For Worse

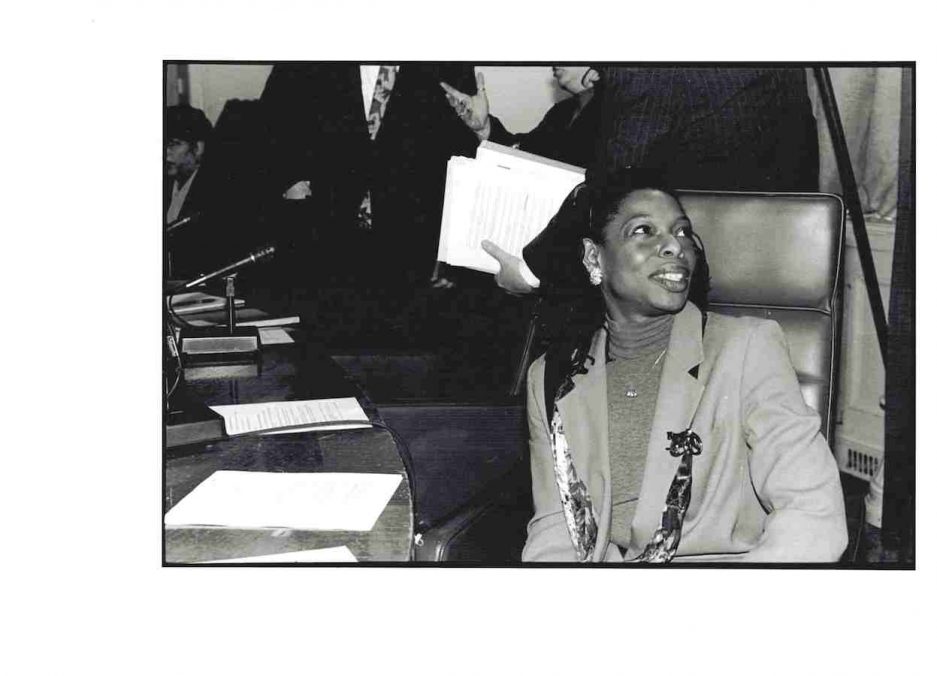

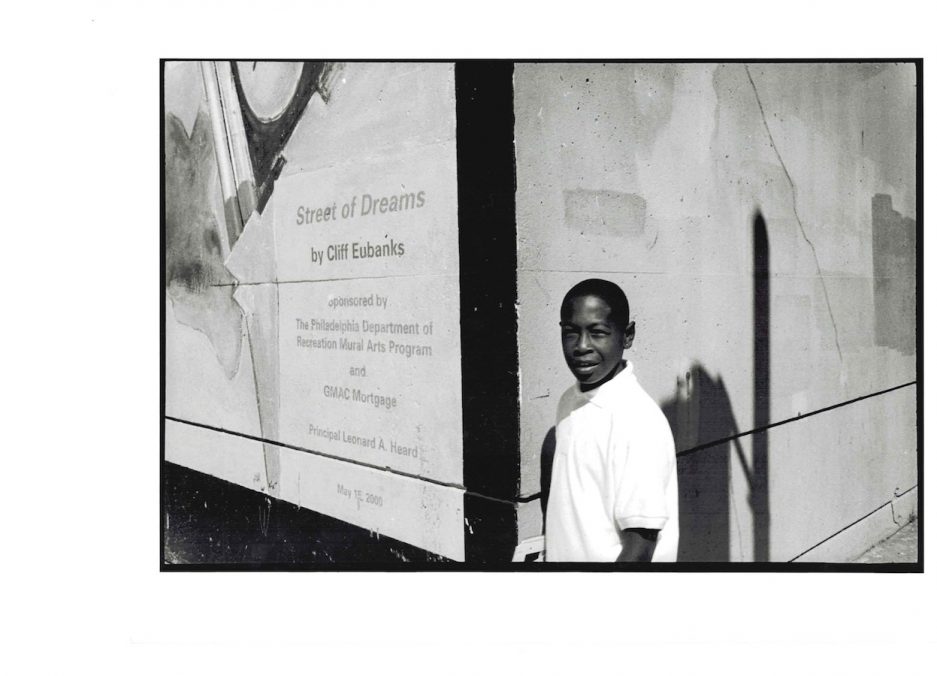

On Tuesday, The Philadelphia Public School Notebook celebrates its 20th anniversary with a celebration at the University of the Arts, complete with music, awards, and exhibitions — including the Harvey Finkle photos you see below — documenting the challenges of covering urban education for two decades. (A 20th anniversary issue has also been published.)

Paul Socolar is the editor and publisher of The Notebook. He talked with Philly Mag about the publication, the persistent challenges of urban education, and how Philly schools might finally be saved.

It’s been 20 years since the launch of The Notebook. What was your aim when it started publishing?

So when we started, really the two main goals were to get information out more widely about what was then and still is a troubled and confusing school system. And also to raise our collective voices about the problems in the system to bring them to public attention. I would say in 1994, there wasn’t the same level of awareness across the city about how desperately in need of change our schools were.

The awareness is wider now, but it’s difficult to argue that Philadelphia schools have actually improved that much during that time though, isn’t it?

Overall, I would say that’s fair, but we’ve made some progress in some areas. But, you know, if the schools were a patient, they’re still more or less on the critical list.

You’ve borne close witness to a number of upheavals in the district over the last two decades. You named them in a recent issue: The state took over the district’s governance, charter schools proliferated, dozens of neighborhood schools were closed, including Germantown High. Of everything that’s happened in the last 20 years, what would you say has been the most momentous, the most important development, and why?

Tough to pick one, but I guess to me, the most momentous change has been the shift from having the monolithic school district where the public schools in the city are all run by one entity to what that’s called the “portfolio model,” the mix of district and charter and some privately managed schools. In some aspects, the system is a lot more complicated than it was back in ’94. In that context, the need for what we do is greater than ever — the need to both help people make sense out of this confusing system, and the need to make sure that this diverse set of schools and school managers is accountable to the public.

These days, alternative media sites popping up all over the place is kind of the norm as everybody sees the media ecosystem fracturing. What you did 20 years ago though, that was relatively novel at the time. Why didn’t you just leave it to the Inquirer to handle?

There were a few things. You know, it kind of is like a whole city. It’s an enormous system that we felt needed a lot more depth than what the daily papers were doing. You know, I think the other thing that’s kind of distinct about The Notebook is that we are very direct about the fact that we are committed to improving public education in the city. We’re not neutral about whether the city needs a good public school system. So The Notebook has a set of values about public education and also a theory of change that inform our publishing. We think that public involvement and transparency and public accountability are really critical to turning around the urban school system like Philadelphia’s. So on that set of issues, we do have an agenda. We’re trying to ensure that the community has a voice in what’s going on in the schools.

Those values — of transparency and community involvement — aren’t always Philadelphia values though, are they?

They’re not always Philadelphia values. They’re not always values in public education anywhere. You know, if you go, for instance, to good suburban school districts, parents have a voice. Parents are very involved and expect the school boards to be very accountable. You know, that’s really critical to making a school system work. It’s hard to do in a big and bureaucratic school system, but ultimately that’s where we’ve gotta get to.

It seems to me that those kinds of values that you’re talking about are slightly at odds with the way Philadelphia has approached education, certainly over the last 20 years, which it seems has been very driven by the idea of bringing in a charismatic superintendent and hoping the cult of personality will win out over entrenched problems.

I think that’s right. I think that one of, kind of, consistent role of The Notebook over the past 20 years has been to try to remind everybody that turning around a school system is going to take a grassroots effort as well as a push from the top — that we really need to change the relationship between schools and communities and, you know, tear down some walls so that families feel like these are their schools, that they’re responsive to them and so on. So, you know, charismatic leadership certainly can play a role in that, but it’s not going to help if the approach is, “I’m the one who’s going to fix everything.” And I think we’ve seen some leaders come through here with very top-down agendas.

One possible antidote to that is there’s been a movement afoot lately to elect a school board directly. That’s never been tried here before, or at least not in modern history. Why haven’t we done that, and what difference might it make

The difference it might make is giving the larger community a sense that their voices are valued. I guess one reason we haven’t done it is that, on the other side, there’s some research that suggests that governance reforms aren’t a magic bullet. That that’s not gonna fix things. I think the big reason we haven’t done it is over the last 12 years, we’ve had a system where the city essentially ceded majority control of the district to the state, hoping in return to get a different level of financial support. It’s pretty clear that hasn’t panned out, and so I think there’s definitely a good reason right now to be looking for some new models. The “elect a board” idea, I guess, is very much back on the agenda for a lot of people.

Last question: What difference would you say The Notebook has made during its lifetime?

There have been types of information shared and kinds of public processes created that I’m not sure would’ve happened otherwise. We’ve certainly broken some big stories, like discovering the buried analysis that showed evidence of widespread cheating statewide on standardized tests. I think the biggest thing, though, is in a troubled system, to create a place, a space, where there is lots of information and rational conversation about: How are we gonna fix this thing? And we’ve just heard from many, many readers about how important that is to them to help them stay in the fight. This is something sooner or later we’ve gotta figure out, or Philly isn’t ever gonna be the great city that people want it to be. I think The Notebook’s biggest contribution is to help people stay in that battle and keep trying to solve it.

Follow @JoelMMathis on Twitter.