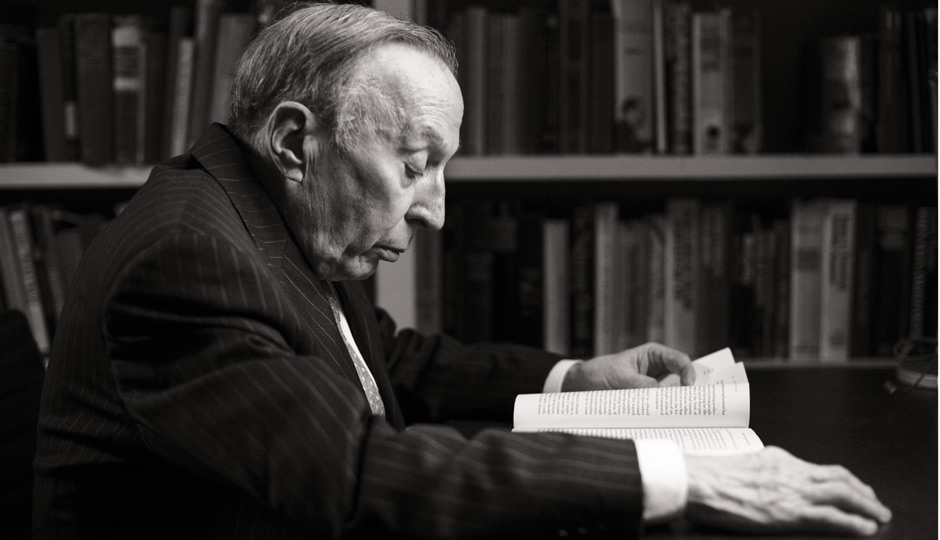

Vince Salandria: The JFK Conspiracy Theorist

ON NEW YEAR’S EVE 1963, Specter got a call from a Yale Law School classmate, Harold Willens. Willens, a Warren Commission staff member, was searching for lawyers to work on the investigation. Already known as a tough prosecutor in Philadelphia, Specter had caught the attention of Attorney General Bobby Kennedy when he sent local Teamster boss Raymond Cohen to jail. It didn’t take Specter long to say yes to Willens, and from that moment forward he was working for the American government, seeking not just the answer to who killed the President, but also for a way to assure the American people that what had happened in Dallas wasn’t a harbinger of the Cold War getting out of control, that the world order hadn’t suddenly gone haywire.

Vince Salandria’s take on the assassination—and his mission—was quite different. But JFK’s killing would become central to his life, perhaps just as much as it was to Arlen Specter’s.

When the President was killed, Salandria was sure of something immediately: If Lee Harvey Oswald didn’t make it through that weekend alive, it meant the U.S. government was complicit in the President’s murder.

Like the rest of the nation, Vince watched on TV as Jack Ruby shot Oswald that Sunday. “I realized then that we didn’t have a democracy, we didn’t have a republican form of government anymore,” Vince says now, 50 years after the fact. “I knew that no innocent government would have permitted Oswald to be killed. Because if he was in fact guilty, they would want the world to know about him, and he would be convicted with due process, and we would show off our democratic justice system. So I realized that … our government did it. At the very highest level.

“I realized that it was dreadful for the nation, and dreadful for me, because I felt that somehow or other I was fixated on it and would have to investigate it. Would I live through this?”

Vince Salandria was a busy man in 1963. He was 35, married, with a young adopted son, and teaching history at Bartram; he was also a Penn-trained lawyer who did legal work on the side. But Vince had a problem. He landed almost immediately, he says, on why he believed President Kennedy was murdered: The military wanted him rubbed out because he had started getting friendly with Russian premier Nikita Khrushchev after the two leaders’ flirtation with holocaust, and because Kennedy wanted to get out of Vietnam; both those things, from the military’s point of view, would be bad for business. So the CIA killed the President at the military’s behest.

Vince wasn’t so bold, though, as to think his investigation would lead anywhere. If his theory was true, he was fighting very powerful forces. And the Warren Commission’s conclusion that the assassination was the work of Oswald—and only Oswald—made the sledding that much tougher for Vince; in 1964, the American public tended to trust that big-name Washington commissions could find, and then would be willing to reveal, the truth.

Vince didn’t believe that, though, and he couldn’t stop himself. He had graduated from Penn Phi Beta Kappa in three years, then stayed to get that law degree at age 23, but he’s fond of pointing out that he comes from Italian peasant stock—his father emigrated from a Southern Italian village by himself at age 13—and that his conspiracy claims stem first from intuition and then from a review of the facts, which he insists in this case aren’t very complicated. As to why he’s so driven in the way he’s driven, that seems innate.

“I was born with an almost underdog complex,” he explains. “I identified with the underdog from the beginning.”

Vince grew up in a South Philly rowhouse across from St. Agnes Hospital, one of eight children. His job as a boy was to deliver clothes uptown for his father, who was a tailor. One day, when he was 13, Vince was cutting through the ghetto and came upon two white cops savagely beating a black man. Blood poured from the man, and the cops kept right on beating him.

“That shocked me,” Vince says. “Power can’t treat human beings like this.”

At the same age—in 1941—Vince would go to school one day in December and regale his math class with the real meaning of what had just happened in the Pacific: The Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor was orchestrated by the American government, he told his classmates. It was President Roosevelt’s way of drawing a reluctant nation into war. That’s the way Vince thought at 13.

It’s quite easy, in fact, to imagine him lecturing his young classmates about the nature of American power, because now, at 85—at the other end of his life—the passion and sureness still flare. There’s no doubting Vince’s sincerity, nor his rage: The President’s assassination scared him, he says, “and it angered me. Angered me! I was furious!”

So off he would go, to Dallas in the summer of 1964—even before the confrontation with Arlen Specter in City Hall—to see what he could learn.

Specter, meanwhile, was hard at work with the Warren Commission, upon which there was enormous pressure. President Johnson had played on the fear of a highly nervous time in wooing high-level Washington figures to join the investigation. Commission head Earl Warren, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, shared Johnson’s message with his staff: Conspiracy theories involving Russia, Cuba, the military-industrial complex, and even Johnson himself were already in play; if they were believed to be true, the President warned, the Kennedy assassination could lead America into a nuclear war that could kill 40 million people.

Lee Harvey Oswald panning out as a lone assassin would, of course, solve those problems. Earl Warren, even as he warned his commissioners that they weren’t advocates, that their conclusions would be based on wherever the evidence took them, had another directive: Make it snappy. The commission was under serious time and budget constraints. Warren would sit in on some testimony Arlen Specter would take from key witnesses, and he had an annoying habit: The Chief Justice would loudly tap his fingers, his signal to Specter to stop asking questions, to be done with it.