How Ala Stanford Became a Champion for the Health of Black Philadelphians Amid COVID

While the city waited for funding, this Philly surgeon launched her own program to bring free coronavirus testing to the Black community. But it’s hardly the first time in her life she’s stepped up.

Ala Stanford, a surgeon, launched the Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium in mid-April. Photograph by Kriston Jae Bethel

It was purely by chance that at the very moment Ala Stanford walked into a revival service at a Philly church last summer, a man fainted and was suddenly unable to move or speak. Frantic and afraid, the man’s wife, a friend of Stanford’s, asked the board-certified surgeon to ride in the ambulance with her husband to ensure that he received proper medical care.

Stanford said yes.

On the ride to the hospital, Stanford told the EMTs she believed the man had suffered a stroke, and based on her advice, the team at the hospital administered a medication that ultimately stopped a blood clot from forming in his brain, sparing him further damage.

Stanford, 49, has a history of rising to the occasion when lives are on the line. In 2018, when Philly’s own Will Smith decided to celebrate his 50th birthday by bungee-jumping from a helicopter 1,000 feet over the Grand Canyon, it was Stanford who was charged with providing advanced trauma life support and triage on the ground. She assembled a team similar to a M*A*S*H unit to facilitate life-saving care for Smith, his family, and the entire production crew in case anything went wrong. She had less than two months to prepare, which, for an event of this magnitude, might as well have been days.

She’s stepped up in other scenarios, too, from delivering medical care without walls during mission trips to Haiti to arranging a Life Flight to a better hospital when a friend was receiving inadequate care. An adult and pediatric surgeon and the founder of her own specialty practice, R.E.A.L. Concierge Medicine, Stanford has always been the one who jumps in without hesitation. For those closest to her, this has been a fortunate, if not lifesaving, fact.

So when the novel coronavirus began spreading through the City of Philadelphia, killing hundreds of people, Stanford promptly filled a rented van with testing supplies, gathered a few volunteers, and began administering COVID-19 tests for anyone who needed them.

These days, you can find her covered almost head to toe in industrial blue; her scrubs, nitrile gloves, protective gown and shoe covers all but completely obscure her rich umber skin. If you catch a glimpse past her surgical mask and protective face shield, you’ll see Stanford’s bright smile, deep-set eyes and pronounced brow line, all of which make her appear at once friendly and formidable.

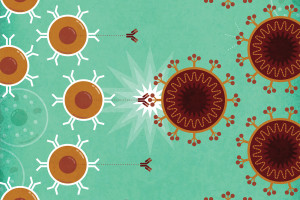

Stanford launched the independent testing effort, formally named the Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium (BDCC), in mid-April, after she learned Black people were being infected by and dying from coronavirus at higher rates than almost any other demographic group. As states across the country began aggregating and releasing racial data for COVID-19, Stanford realized that people living in majority-Black counties were infected at three times the rate and dying at almost six times the rate of people living in majority-white counties. This came as no surprise. Stanford knew that factors ranging from pre-existing conditions to the high number of Black people working essential jobs to the history of Black people being treated unfairly by the medical community would undoubtedly affect their access to testing, not to mention their willingness to be tested for the virus.

Her effort was groundbreaking. Because theirs was the first mobile testing program in the city, Stanford’s team was able to reach communities that were being disproportionately affected yet underserved.

This was largely possible because Stanford didn’t hesitate. Unlike city government officials, who waited months for federal funding before launching any testing efforts specifically aimed at the Black community, Stanford used her own funds to purchase a wad of tests and began hosting testing events in community centers and churches in and around Philadelphia. She and a group of physician volunteers administered coronavirus tests for free, in parking lots and on street corners, to all those who registered, whether they had health insurance or not.

“I didn’t know how I was going to get paid,” she says, “but I said I’ll figure it out on the back end, because I’m not going to have people not getting tested and not getting what they need when I have access to provide it to them.”

Stanford spent the next few months putting her all into the BDCC effort, because, as at so many other times in her life, she was simply unwilling to back down. That indomitable spirit has guided her choices since she was 13 years old.

When she was growing up in North Philly, Stanford always knew she wanted to become a doctor. She can remember writing in her class yearbook as early as eighth grade about her dream of earning a white coat. Her love of children, and perhaps inspiration from her father, who worked for Pennsylvania’s Department of Children and Youth for more than 30 years, inspired her to specialize in pediatrics. Stanford chose surgery as her subspecialty because, as she puts it, “People didn’t expect girls like me to become surgeons.”

During her time in medical school, Stanford says, she and other inner-city students were strongly encouraged to become primary-care doctors, roles that typically led young physicians toward lower-paying jobs in community health centers rather than more lucrative ones in leading hospitals and academic medical centers. “I felt like they were forcing me into this category, so I rebelled against that,” she says.

She went on to complete her residency in general surgery at the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, as well as two fellowships, one in research at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh and one in pediatric surgery at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. She earned the title of board-certified surgeon in 2007.

But as her career in medicine advanced, Stanford noticed some people’s skewed expectations and stereotypes of her persisted. “People just didn’t expect an African American woman to attain certain heights, so the expectations were lower sometimes,” she explains. “Then when I’d try to surpass them, I’d be told I was doing too much. They’d go from saying ‘She’s not aggressive enough to be a surgeon’ to ‘I hope she doesn’t think she’s going to just smile her way through surgery training.’ And it felt like weights on my ankles, pulling me down. Being a Black woman, trying to defy those expectations — that was and still is my biggest challenge.”

Over time, Stanford says, she’s learned to forge past people’s narrow opinions of her and the sizable goals she tries to accomplish. One of those big ideas manifested as R.E.A.L. Concierge Medicine, a private practice she established in 2014 to provide discreet personalized health-care services for business executives, athletes and entertainers (like Will Smith). But her services aren’t reserved only for the rich and famous. On several occasions, her practice has created mobile ICU units to allow terminally ill patients to travel and participate in family functions without jeopardizing their safety. “R.E.A.L. Concierge Medicine definitely prepared me for this work with the Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium, because it allowed me to think outside the box in terms of how I take care of people,” she says.

For Stanford, whether she’s caring for a celebrity or a member of the local community, discretion and compassion are paramount. They’re both traits she aims to instill in her three preteen sons, Ellison, Langston and Robeson, all named after men of the Harlem Renaissance. When she’s not saving lives, she enjoys spending time with her children, traveling with her husband, and visiting Martha’s Vineyard. When she’s alone, Stanford says, she spends a lot of time reflecting on her life’s purpose and thinking of ways to “use the gifts that God gave” to make a difference in the lives of others. “Certain people aren’t going to like you; certain people won’t think you’re capable. And you have no control over that. So there’s no point losing sleep and time on people who are set in their ways about what they believe,” she says. “I really see it as a privilege to be able to do what I do, and I believe that shows through in my work and my ethics.”

When Stanford began reaching out to find physician volunteers to help the BDCC with testing, the response was overwhelming. Everyone from old medical-school classmates to colleagues she’d worked with in the past and medical students she’d never met signed up to help administer tests at the group’s community events.

Jefferson Health physician and BDCC volunteer Pierre Chanoine says it was Stanford’s charismatic get-it-done personality that made others want to support the effort. He recalls having to tell her during one of the BDCC’s first testing events that the group had run out of test kits while there was still a long line of people waiting. Stanford refused to turn a single person away. In her signature fashion, she quietly stormed off and made a few phone calls, and within an hour, a new batch of test kits was delivered to the site.

“She’s incredibly caring and thoughtful but definitely no-nonsense and kickass,” Chanoine says. “She’s one of those people who just make things move.”

No one echoes that sentiment more than Natalie Gonzalez, a recent graduate of the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine and BDCC volunteer. Gonzalez was one of many students who saw their commencement ceremonies canceled amid the pandemic. Before her residency started in July, she threw herself into volunteering for the BDCC, recruiting new volunteers and sometimes working back-to-back testing events. On what would have been Gonzalez’s graduation day, she showed up at one of the BDCC testing sites, and Stanford threw her an impromptu ceremony.

Registered nurse Shelah McMillan has looked to Stanford as an inspiration and mentor ever since the surgeon performed a life-saving operation on her daughter 14 years ago. The two stayed connected over the years, with Stanford offering guidance to McMillan on how to take her own career in medicine to new levels. When McMillan heard about Stanford’s BDCC effort, she was among the first to sign up to volunteer — not only because she views Stanford as her daughter’s savior, but because she felt inspired by the doctor’s love for her community.

“When you talk to her, you get entranced,” McMillan says, “because you can tell she cares about you and wants you to succeed.”

The BDCC remains a resource for those who can’t or prefer not to be tested in traditional health-care settings. During BDCC’s first 30 sessions, the group tested about 6,000 people, 96 percent of them Black. After the BDCC had spent months providing testing services with no support from the city, Mayor Jim Kenney in June awarded the group a grant to continue providing testing to marginalized communities through the end of 2020. The BDCC’s initial response to the city’s request for proposals asked for $6.9 million to provide coronavirus testing and related services. The city estimated that the final grant award would be much lower, in the range of $1 million. The delay and the paucity both rankle. “So many people want to tout this as a partnership now,” Stanford says, “but while we were doing the work, they weren’t giving anything. They said they wanted to help us but never asked what was needed.”

While Stanford plans to continue leading the BDCC and her private practice, she says she’s already considering how she can play an even bigger role in improving health outcomes for Philly residents. “I need to see progress in whatever I’m doing. So I’m open to the possibility that I could end up helping to improve public health policy for African Americans, because they need a champion,” she says. “I don’t know that I’ll be the voice for the nation, but I can certainly be a voice right here in my city.”

Published as “Passing the Test” in the August 2020 issue of Philadelphia magazine.