Q&A: BIO CEO Jim Greenwood on Philadelphia’s Biotech Future

The leader will bring his 17,000-person global convention to Philadelphia next week. Here are his thoughts on Philly’s gene therapy boom and why we all still have so much to learn about biotechnology.

BIO president and CEO Jim Greenwood at the 2018 BIO International Convention. Courtesy photo.

Next week, nearly 20,000 life sciences professionals from around the world will descend upon Philadelphia for the highly anticipated 2019 BIO International Convention. The mega conference will shed light on the region’s major life sciences strides and bring the world’s key players together to see firsthand what’s underway in the region. According to the organization, Greater Philadelphia employs 45,000 workers across biotechnology, pharmaceutical, medical device and diagnostics, and digital health companies.

NextHealth PHL sat down with the organization’s president and CEO Jim Greenwood, a Philly native, to find out why the BIO Convention is back in Philadelphia (the city previously hosted it in 2005 and 2015) and how the conference only adds to Philly’s enduring salvo for innovation and discovery.

NextHealth PHL: Talk a little about yourself. How did you make the jump to leading BIO?

Greenwood: I was a social worker, and then I was in the Pennsylvania House for six years and the Pennsylvania State Senate for six years. In the last few years I was the chair of the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations. One of the things I investigated was cloning. I watched a 60 Minutes show one night, and there was this guy Dr. Zavos. They had just cloned Dolly the Sheep, and he said he was going to clone people. His pitch was, “If your child died, at whatever age, give me some DNA, a hair from a hairbrush or something, and I’ll reproduce them.” I thought that was wrong. I had been a social worker with neglected children, and I thought every kid is entitled to be the unique product of a father and a mother, and not just a clone of somebody else.

I started an investigation, and during that, the president of BIO visited me and said, “We agree that reproductive cloning is not a good idea. But there’s a thing called therapeutic cloning where we actually do somatic cell nuclear transfer. You create an embryo and extract embryonic stem cells from that and use them to take a human cell and turn it into any other cell.” They could make it a pluripotent stem cell, which means it’s a stem cell that can be turned into anything.

Did his proposition motivate you in some way?

Yes. So I’ll give you a little biology that I had to learn. When an embryo begins—when a fertilized egg divides—in the first several divisions, all of the cells are identical. Then as the embryo grows, they begin to specialize to become bone cells, and skin cells, and blood cells, and hair cells. The mystery is how do these pluripotent cells become specialists? The idea was if we could figure out how to take these cells and say, if you had a heart problem, we could make heart cells from your own body.

I wanted to preserve that, and BIO convinced me that I should legislatively prohibit reproductive cloning but protect therapeutic cloning. That’s how I got to know them. Then, after I was serving my sixth term, I was a candidate for my seventh term in 2004. I got a call from a headhunter saying, “BIO is replacing its president, are you interested?” By that time I had been in elected office for almost 24 years, maybe it’s time to do something different. This sounded fascinating, so I threw my hat in the ring.

In your time with BIO, you’ve visited biotech hubs around the world. What do you think makes for a thriving biotech scene?

The biotech industry started in San Francisco and in Boston. That was because of the fabulous institutions of higher learning there. In the very beginning, between Harvard in Boston and the University of California San Francisco, there were companies competing to do the first biotech insulin. In any case, to have a biotech hub you have to have great universities, and those universities attract NIH funding. So a lot of basic research is done. That’s the first step.

From there, the next thing is: Do the universities have good tech transfer programs? Do they just do the research and shelve it or do they actually try to license it out to the private sector? That’s critical. It’s very helpful if you have state and local plans that help develop incubators and help people get through the “Valley of Death” when they don’t have any revenue. It helps to have good hospitals, as Philadelphia does, where you can do clinical trials and where there’s a vibrant medical community. And then the last thing: It has to have venture capital coming in, and that’s always the last step and always the hardest one.

That BIO’s convention will come to Philadelphia next week is a big deal for the city. What do you see as Philadelphia’s position in all of this?

Today, when we ask people, “Where’s biotechnology in the U.S.?” they’ll still say San Francisco. They’ll say San Diego, which is considered by some to be the No. 1 biotech hub. San Francisco, Boston, the Research Triangle in North Carolina. The Philadelphia region is No. 6, after the Washington-Maryland areas. It’s significant.

People tend to think, “If we want to be a biotech hub we have to draw companies from other cities to here.” It’s really not the case. It’s not like you have to get a football franchise out of some other city. We have an infinite amount of knowledge to gain about biotechnology, an infinite amount of applications. So if you have the ingredients I mentioned, you can just keep growing your hub and the more you grow it, you reach a critical mass of people. When you have that many people employed by big pharma, like in this region with GSK, Merck, AstraZenaca, then as you spin out smaller companies, they can draw employees and scientists from the bigger ones.

What else stands out to you about Philadelphia?

The other thing about Philadelphia is in 1999 at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Dr. [Jim] Wilson was doing the very first gene therapy. This young man, Jesse Gelsinger, was in a small clinical trial and he died. That really put a chill on gene therapy as a whole. What’s really quite poetic is that Spark Therapeutics now has the very first ever FDA-approved gene therapy product. There’s a lot going on in the gene therapy space here in Philadelphia. It’s really kind of cool.

Onlookers are worried about the high price of the therapies. Do you think that’s going to be a roadblock to the growth of the region’s industry or is it something the region can overcome?

Could be. No one should ever do without medicine they need because they can’t afford what’s out-of-pocket. If we’re going to do these $1 million one-time [gene therapies], I think we have to make sure that the patient’s out-of-pocket isn’t a problem. That still leaves the payers, whether they’re public payers, private payers, with the problem. So what we have to do is say, “If you’re going to cure somebody for life, you should be able to pay over the course of a patient’s life.” So if it’s $1 million, you’re not going to pay upfront. Take Spark Therapeutics. They cure blindness in children. Let’s say it costs $900,000. We can divide it by some reasonable expectation each year, and if it stops working, you stop paying. There are ways to spread out the cost over time that should make it acceptable.

What else is exciting to you in the industry right now?

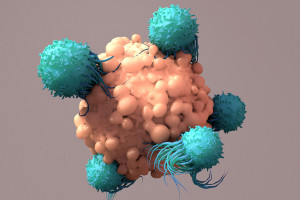

In terms of not only gene therapy and the cell therapy, immunotherapy is really hot now. We have these wonderfully developed immune systems that fight viruses and bacteria, but they don’t fight cancer. Cancer has “figured out” how to thwart the immune system. So these immunotherapies thwart the thwarting system and allow the immune system to attack and fight off the cancers.

Jimmy Carter is the perfect example of that. He thought he had a few weeks to live and he took Merck’s Keytruda product for metastatic brain cancer, started with a melanoma, and he’s in complete remission.

How has the BIO convention grown to what it is now?

This will be our 26th convention. In the early days of BIO, we started out with like 700 people. Part of the idea is we’d just go anywhere around the country and proselytize biotech. We grew and grew and grew and went to Atlanta, and 10,000 people showed up. There’s just not enough interest in biotech there.

10,000 isn’t a lot of people?

Our record is 22,500 people in 2007. We tend to go to Boston, San Francisco, San Diego. Philadelphia has been in that circuit as well because it is a significant hub.

This year we will have like 17,000 people here from 70 countries. They will be the biotech leaders of those countries. Many things happen. The exhibit hall will have pavilions from a number of countries and states. Then there is a group of several thousand people who come just to do business-to-business meetings. They want to meet with other companies to talk about licensing deals, investment deals, mergers, acquisitions. Out of those meetings comes a geometric growth in the industry because all of this collaboration occurs.

Then we have 19 educational tracks where you can learn about policy, science and the business of biotech. We have keynote addresses and speakers in 118 sessions. We have a thing called Startup Stadium, which is where we take companies that are just getting going.

Speaking of those fledgling companies, what’s your advice for local biotech start-ups? What should they know about where the industry is headed?

You have to put a premium on innovation. The world is not looking for another me too drug. If you really want to succeed, you have to meet an unmet medical need. You can make the 15th toenail fungus medicine if you want, but you’re not going to get paid a premium for that. If you’re really on the cutting edge of the science, if you’re really an innovator, meet an unmet medical need in a new and better way than has been addressed in the past. You’ll succeed…eventually.

Looking forward, what are you worried about?

The big worry on the horizon is the policy. If in the effort to try to do something about out-of-pocket costs, lawmakers and presidents, are ham-handed in their policy approach and just are out to punish the biopharmaceutical industry, they’ll succeed. We’ll get cheap drugs, but we won’t get new drugs. It’s too risky to invest in this enterprise and fail 90 percent of the time if you’re going to put price controls and those kinds of limitations on it. My biggest fear is that policy will destroy all of this hope.

On the scientific side, the only real things to worry about are people who are not being sufficiently responsible in terms of risks. Gene editing is an important development now—we have this thing called CRISPR-Cas9. The ability to very easily edit genes has miraculous potential. Like this guy in China, you don’t want to be reckless and give gene editing a bad name, the way GMOs got a bad name in agriculture. I also worry that out-of-control scientists who are either unethical or sloppy will in some way damage the science with some unintended consequences.

Earlier you listed a few key elements that make for a thriving biotech hub. What can Philly do to get better at those things?

I think it’s important for the biopharmaceutical community to have strong relationships with all of the universities. If you go back in history a bit, there was a tendency in academia to say, “We’re not about money. We’re just academics.” But even if you’re not sure what the discovery might have in terms of applied usage, you need to get it out there and let people look at it and see if they can find a use for it.

My speechwriter and I were working on a speech I’m going to give at the convention. We’re trying to capture this notion that gene therapy is on the map in Philadelphia and how it’s been resurrected. We’re thinking about using analogies like Rocky Balboa or the Eagles getting the Super Bowl. [Laughs]