One Way to Reduce Center City Traffic: Ban Private Cars

Dublin has one-third the population of Philly and is tucked within one-third of the square mileage. It’s comparably dense, but many times more congested. In the annual congestion rankings of the world’s most populous cities, Philadelphia comes in at 136; Dublin at 18. Your average commuter in Dublin faces 103 hours of delays over the course of year. That’s a full a day and a half longer spent in traffic than the average Philly commuter.

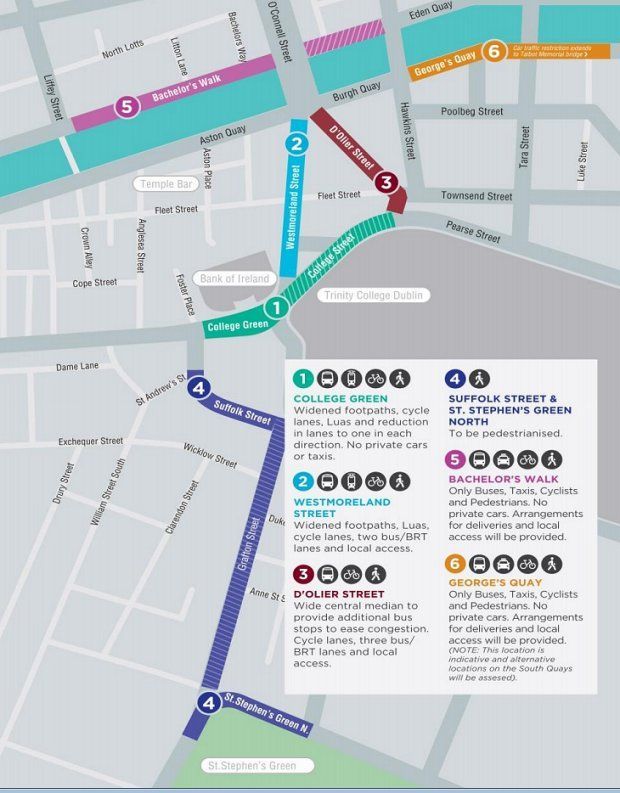

Meanwhile, the Irish government is predicting that the greater Dublin area could grow by as much as 14,000 people per year in the coming decades, meaning that commuter congestion is bound to get substantially worse. People entering the city during weekday peak hours is expected to rise by 20 percent in the next eight years. That’s why the Dublin City Council has moved forward with a proposal to curb automobile traffic in the downtown area. And it’s really bold.

They’re banning cars from big sections of downtown.

If it works, the no-car zone could expand over time.

Dublin’s aim? “To safeguard the future growth of the city, both in terms of general economic development and more specifically in terms of new transport infrastructure,” according to a comprehensive Transport Study conducted by the Dublin City Council and the National Transport Authority.

Maybe that’s good for the Irish, but could a car ban cross the Atlantic and take hold in auto-happy American cities like Philadelphia?

It sure didn’t work last time the city tried.

Anyone remember the the Chestnut Street Transitway? In the year Philly celebrated the Bicenntenial, a stretch of Chesntut was converted into a pedestrian mall. It was a pint-sized version of Edmund Bacon’s plan to make Walnut and Chestnut Streets car-free from river to river. The Transitway was limited to 12 blocks, and 1,000 SEPTA buses barreled down the thoroughfare each day. Not exactly a pedestrian paradise. (It’s notable that Dublin’s plan also allows for regular bus routes to operate on streets where personal vehicles are banned.)

Bacon later criticized the Transitway, saying it “failed miserably” to capture his idea. Many businesses closed, and the project was widely considered a failure. The Transitway was reopened to vehicle traffic in the late 1990s. Does the failed experiment mean Center City is destined to have car-dominated streetscapes indefinitely? Not exactly. As a NextCity story put it a a few years ago:

Just like with the Chestnut Street Transway, misallocating street space or designing streets to accommodate only cars or only transit can destroy wealth and render commercial properties unattractive to businesses and their customers. Bacon’s “No Private Cars” mantra was too radical for his day, when the nation’s car culture was ascendant, and it is too radical now. But there is growing agreement that fewer private cars is key to successful neighborhood retail clusters.

And maybe now, in a day and age when bike travel is more common and Center City sidewalks are as heavily used as they’ve been in decades, there’s a case to be made for trying to close off another street to private vehicles.

I asked some of the city’s urban-planning junkies on social media for their input. With the lessons of the Transitway in mind, most people offered streets with limited bus routes as options: 9th Street between Washington and Christian in the Italian Market; small alley-like streets such as Drury, Chancellor and Juniper; Sansom between Broad and 18th. Those seem like feasible options because they’re not heavy on bus traffic and it wouldn’t change the character of the streets as they stand — being popular avenues for pedestrians already.

Would City Hall — which sometimes struggles simply to get bike lanes put in — have the political will to actually shut down Center City blocks to private vehicle traffic? That’s another story. But Councilman Mark Squilla said the Dublin proposal was “interesting” and he would “be willing to enter into discussions with the Planning Commission and stakeholders to determine the best approach.”