Did LaFaye Gaskins Really Murder Albert Dodson?

Photograph by Claudia Gavin

LaFaye Gaskins, inmate number BF8329, is serving a life sentence for first-degree murder at the State Correctional Institution at Mahanoy, a two-hour drive northwest of Philadelphia, in the heart of old anthracite coal country. Gaskins is a lanky 47-year-old black man with a large bald head that glows beneath the fluorescent lights in Mahanoy’s visiting room. The first time I meet him there, in June 2014, Gaskins chuckles softly and often as he tells me his sad, surreal story. But he’s spent nearly three decades in prison, and his humor has an edge. When I mention the room’s teal-and-white color scheme, Gaskins deadpans, “In prison, brighter colors are supposed to calm you down.”

He was meticulously prepared for each of our meetings, precise and detailed, as he was in every phone call and letter. “I’m still alive and healthy, and I just want an opportunity like everyone else,” he told me during one recent conversation. “I don’t have no animosity toward no cops or none of that. I just want to come home.” Beneath his smile and carefully crafted memos, Gaskins’s heart must be pounding. He has only the narrowest of paths toward freedom. “This is the first time somebody’s taken an interest in my case,” he says, knowing that it might also be the last.

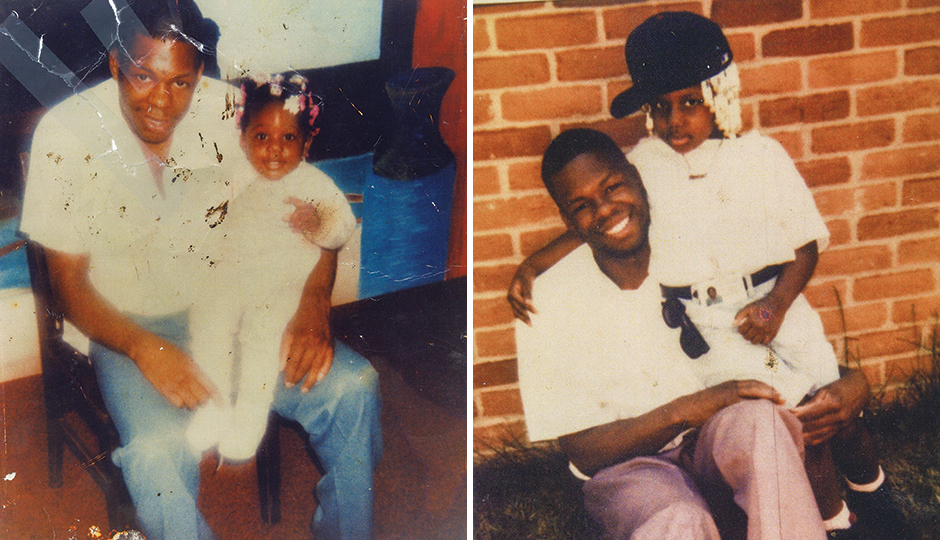

Gaskins has few visitors. In 1998, his younger brother died from AIDS complications. Today, his regular contact with the outside world is limited largely to his mother, Myra Gaskins, and his daughter, Onia Gaskins, a 27-year-old petty officer second class stationed at the Coronado naval base, near San Diego. She was born just a few months before Gaskins was arrested. “It’s missing prom,” says Onia. “Missing the little in-between, the simple things in life. I had to get to know my dad before I could love him.”

On May 1, 1990, a Philadelphia jury found LaFaye Gaskins guilty of murdering Albert Dodson, a 42-year-old drug dealer from Virginia who was in Philadelphia to buy cocaine. Gaskins, then just 20, was also a drug dealer, raised in the Raymond Rosen projects of North Philly — and he carried a gun. Prosecutors presented jurors with a simple, believable narrative: Gaskins set Dodson up, killed him, and stole most of the $20,000 Dodson had brought with him in a drawstring bag for the buy.

The year Dodson was killed and the year Gaskins was convicted were the two bloodiest in Philadelphia’s history: 476 people were murdered in 1989, and 500 in 1990. The causes were complex, but the media and political narrative wasn’t: Drug dealers like LaFaye Gaskins were public enemy number one. Headlines screamed of the threat posed by the Junior Black Mafia. In a New York Times/CBS News poll, 64 percent of Americans named drugs the nation’s most serious problem — one of the highest totals ever recorded by that poll for a single issue.

There was no physical evidence tying LaFaye Gaskins to the murder of Albert Dodson — no conclusive proof that he ever even met the dead man. The entire case against him rested on the testimony of two dubious eyewitnesses, neither of whom claimed to have seen the actual shooting. And yet jurors took about three hours to unanimously decide that Gaskins was guilty. Seen through the lens of 2016, the evidence appears risible. But social context matters in justice, and in fear-gripped 1990 Philadelphia, the public presumed drug dealers guilty of the worst.

Flash-forward a quarter century, and the context has changed. Violent crime rates are at record lows, and 58 percent of Americans support legalizing marijuana. Outside of Gaskins’s circumscribed universe, a movement for criminal justice reform is beginning to crack the walls of a prison system that incarcerates roughly 2.2 million people, including 85,200 in Pennsylvania. Sentencing reforms, however modest, have bipartisan support in Congress. Juvenile offenders are winning new rights in the courts. Meanwhile, wrongful convictions have become something of a national fixation, judging by the runaway success of investigative docudramas like Making a Murderer and Serial (100 million downloads and counting).

Only there are no high-school sweethearts in the story of LaFaye Gaskins and Albert Dodson, no clan of junkyard misfits. The case was extraordinarily ordinary: one black drug dealer shot dead, another charged with his murder. Dodson lived on the fringe of society. So did Gaskins, the witnesses in the case, and a host of other potential suspects. Some of the individuals linked to the case are now prematurely dead, in prison, or living off the grid.

In 1990, Philadelphia’s criminal justice system imprisoned LaFaye Gaskins for life without any credible evidence he actually committed the crime, and nobody blinked — not then, and not now, even as the eggshell-thin foundation of the original case against him has shattered.

There’s not enough outrage to go around for the even more stark miscarriages of justice: the convicts proved innocent by DNA evidence after decades of wrongful imprisonment; the court battles over life sentences still being served when someone else has credibly confessed to the crime. And those are the singular dramatic exceptions — outnumbered a ton to one by cases like LaFaye Gaskins’s.

Philadelphia District Attorney Seth Williams is the one man positioned to get Gaskins a new hearing. Right now, that appears unlikely: Williams’s default position is to fight like hell to keep men like Gaskins in prison.

Even when the evidence is overwhelming that he never should have been convicted.

Two shots of LaFaye Gaskins with his daughter, Onia Gaskins. | Photographs courtesy of LaFaye Gaskins

GLORIA PITTMAN PROBABLY got high on the day Albert Dodson was murdered. She got high most days back then. Pittman started using heroin in her teens, but by the late 1980s she was addicted to crack, which had become the street drug of choice for many young people in Philadelphia.

Pittman led a tumultuous life. Her record includes arrests for prostitution, robbery and drug dealing. In 1972, she killed a man. Her victim was known as Muffin. He was a heroin addict Pittman knew, and he’d tried to steal a TV from her home. In response, she grabbed a fully loaded .38 revolver from her sofa, found Muffin, took the revolver from her purse, and shot him twice. Nearby police heard the shots and apprehended her while she still held the gun.

Remarkably, Pittman only got probation for that shooting. It’s unclear why. But she was a free woman in February 1989, 36 years old and living in a house on Mount Vernon Street in Mantua on the day Albert Dodson likely died.

She later told police that she’d seen three men hanging out near an abandoned house across the street from hers. They were “laughing and talking,” Pittman testified in 1990, “drinking beer.” At the time, Pittman was preparing to cook powder cocaine into crack. “I cook it up,” she tells me, almost three decades later, “like, with baking soda, water, you put it on some fire. … When you see a gel, you put cold water in it, and then it turn into a rock.”

A short time later, Pittman heard what sounded like a shot and ran to her second-floor window. She saw a man leaving the abandoned house, holding a bag. Pittman didn’t make too much of it.

But a few days later, a friend of Pittman’s found Dodson’s frozen corpse inside the abandoned house. He’d gone inside the building to relieve himself. “It’s a dead body in there,” he told her.

When police arrived, Dodson was lying on the abandoned home’s debris-strewn floor, a casing from a 9mm gun by his right foot. The Virginia drug dealer had a Gucci watch strapped to his wrist and $712.13 tucked into his coveralls that couldn’t be removed until his frozen body thawed. A bullet had entered his face just next to his right eye. Gunpowder residue indicated the gun had been fired at close range.

When a detective showed up to interview Pittman, she told him what she had seen and what she had not.

DID NOT SEE FACE, the detective’s notes read.

From left, Onia Gaskins in her Navy uniform; LaFaye with his mother, Myra Gaskins. | Photographs courtesy of LaFaye Gaskins

A MAJOR LEAD came fast and easy in the Dodson homicide: A North Philadelphia man named Edward Clyburn was in possession of the murdered man’s car.

As Clyburn told it, he and the victim had been good friends. They were so close that Clyburn was with Dodson most of the last day he was seen alive as the Virginia man sought to purchase a large quantity of cocaine. Clyburn stressed to police that he wasn’t in on the deal; he was just along for the ride.

Clyburn told police that he and Dodson met up with Dodson’s supplier, a man named Wayne “Junnie” Hampton, outside a North Philly McDonald’s. Junnie was 22 years old, short and clean-shaven, and he radiated the symbols of street-derived opulence. Another witness in the case said Junnie drove a new white Mercedes and a black Corvette, and that he wore “a lot of gold jewelry” alongside a “lot of gold in his mouth.” Junnie was accompanied by two associates whom Clyburn hadn’t met before.

From there, Clyburn’s account to the police gets weird. After the group left McDonald’s, Junnie bailed, leaving Clyburn and Dodson with his two associates. Following a series of peculiar fits and starts, the foursome finally headed to West Philly, theoretically to pick up the cocaine. Clyburn was getting nervous. “Al, this is a rip-off,” he scribbled onto a torn-up matchbox, and handed it to his friend as they drove.

Dodson threw it out the window. “Man, you crazy,” he said.

About 5 p.m., Dodson parked the car off Lancaster Avenue. Dodson and Junnie’s two associates got out, but Clyburn stayed in the car. They didn’t come back. Clyburn waited an hour for his friend, then drove home.

Or so Clyburn said at the time. I wasn’t able to locate Clyburn. Public records show that a man named “Edward Clyburn,” of the same age and with a string of gambling charges, died in 2000.

Clyburn never claimed to have witnessed the murder. But the picture he painted for police would shape the case as it moved from investigation to trial: Junnie’s two associates lured Dodson to the abandoned house, robbed him, killed him, and left his body to freeze.

LAFAYE GASKINS GREW UP on the ninth floor of one of Raymond Rosen’s towering projects at 23rd and Diamond. He and his younger brother, Michael, were raised by their mother, Myra, a thrifty woman who patched together welfare checks and jobs, stuffing junk-mail envelopes and changing diapers at a nursing home. Their father had left the family when LaFaye was about four, and LaFaye fought, with his fists, to stick up for Michael, who was frequently picked on.

Gaskins says that at 14 he started snatching purses and was arrested multiple times. At 17, he started dealing drugs. The allure was simple enough: Dealing promised money and respect on the street. He bought brand-new shoes. He peeled off a $20 bill and paid a guy waiting at the barber to let him jump in line.

Gaskins and Junnie were tight. Gaskins says it was Junnie who introduced him to selling drugs, and that the two were business partners: They would buy wholesale from a Puerto Rican in the Badlands and then separately distribute smaller quantities to other dealers. If Dodson had indeed been killed by Junnie’s associates, Gaskins would be a prime suspect. (Wayne “Junnie” Hampton is currently serving time in a state prison on an assault charge. He didn’t respond to letters seeking comment.)

It was another man from the same neighborhood, Ralph “Donut” Taylor, who appears to have focused police attention on Gaskins. Donut, whose parents owned a laundromat and shop in the neighborhood, knew everybody involved. And Donut told police that Junnie, Gaskins, and Junnie’s uncle, Henry Howard, paid a threatening visit to his parents’ shop not long after Dodson’s body was found. He said the uncle did most of the talking, insisting that Junnie had nothing to do with the murder and warning Donut not to tell police otherwise. “They said to me that if I told the police anything like Junnie had anything to do with killing Al, I would get messed up,” Donut said to detectives.

Gaskins says he had nothing to do with Dodson’s murder. He says he wasn’t at the McDonald’s, and that he never got in a car with Clyburn and Dodson. He says he was just a few blocks from his mom’s home in North Philly, staying with Junnie’s aunt, when Dodson was murdered in Mantua (an alibi so thin that it wasn’t raised at trial). But Gaskins freely admits that he went with Junnie to visit Donut. Gaskins tells me he tagged along because Junnie asked him to do so. That, he says, is how such business relationships worked in North Philadelphia. “I need you to come with me,” he recalls Junnie saying: “I just came along.” More than any of the witness testimony, this acknowledgement — which was never shared with the jury — makes Gaskins a plausible suspect in the murder of Albert Dodson.

But there are many others who should have merited a close look, starting with Junnie and Junnie’s mysterious second, unidentified alleged associate — who, like Junnie, was never discussed much in court. Clyburn, Dodson’s friend, also seems worthy of scrutiny; he admitted being with Dodson in the last hours of his life, had been in possession of the dead man’s car, and curiously claimed he was just a friend along for a high-risk ride. As for Donut, Junnie’s family says he’s still somewhere in his old North Philly neighborhood, and in rough shape. I couldn’t track him down.

More broadly, Dodson was known to be an out-of-town drug dealer who carried large amounts of cash, making him a ripe target. Henry Howard, Junnie’s uncle, suggested as much when I met him recently at his North Philadelphia home. A lot of people knew that Dodson came to Philly to buy drugs, and a lot of people knew that meant he carried a lot of cash. Clyburn described Dodson as both reckless and paranoid, telling police that in the days before his murder, Dodson had left a drug-fueled get-together with a prostitute because he was worried about the $20,000 in drug money sitting in his car parked outside: “Al said he’d be back in a few minutes but never came back.” Dodson later told Clyburn that he’d then been pursued by a black SUV all the way into New Jersey.

IF POLICE FOLLOWED that lead, or any other, there’s no evidence of it in the documents that I obtained. They had zeroed in on Gaskins.

This might be because some members of the Philadelphia Police Department apparently believed he was a senior member of the Junior Black Mafia, among the most notorious and violent Philadelphia gangs of the era. JBM, as it was often called, had ties to the Italian Mob and an affinity for violence.

Gaskins obtained a police document dated Thursday, June 1, 1989, that reports on a meeting between Philadelphia detectives and a Drug Enforcement Administration agent. The document quotes an unnamed DEA inside source who identifies Gaskins as a member of JBM’s “board.” The source says Gaskins claimed he would fight back if the police came: “I will not be taken alive, I will take some of those heroes with me,” Gaskins allegedly declared. The source “believes that LaFaye Gaskins is serious when he makes that claim.”

But I doubt Gaskins had any meaningful ties to JBM, and not just because of his explicit denials and the clichéd improbability of his purported vow to “take some of those heroes” with him. The state Department of Corrections maintains a database of prisoner gang affiliations, including a long list of those with JBM ties. A law enforcement source searched that database for me and found no listed link between Gaskins and the Junior Black Mafia.

Whatever their reason for targeting Gaskins, police were looking at a tough case. There was no physical evidence linking their prime suspect to the murder of Albert Dodson — no blood splatters or fingerprints, no recovered weapon, no video. All police had were their witnesses: Gloria Pittman, who saw three men outside the crime scene and one man fleeing it; and Clyburn, who said he had driven with the victim and two mysterious men to a nearby block. And their stories just didn’t sync.

Pittman had told police on the scene that the man she saw leaving the house was wearing a “two-tone” jacket and sported a notable “box haircut.” In a later police interview, she added that he was wearing blue jeans. Clyburn, meanwhile, had described a man police later claimed was Gaskins as wearing “a light color sweater over a button shirt [that] wasn’t tucked in” and “dress pants.” He made no mention of a haircut.

The two lead witnesses didn’t agree on the timeline, either — at least, not at first. Pittman remembered hearing the gunfire between noon and 1 p.m., on a Wednesday. Clyburn, though, told police that Dodson left the car around 5 p.m., when the sun was setting, on Tuesday. He told detectives he waited for an hour, then drove home alone.

Even in fear-gripped 1990, conflicting stories from witnesses like these probably wouldn’t be enough to win a conviction. But the more police and prosecutors talked to their witnesses, the closer their stories became, and the worse matters got for Gaskins.

First, the witnesses changed their timelines. By the time of the trial, Pittman was testifying she heard the shots on Tuesday, not Wednesday. Still more peculiar was Clyburn’s shifting timeline. After originally telling police he arrived in Mantua with Dodson and Junnie’s two mysterious associates at 5 p.m., Clyburn testified that they got there at 1 p.m. Then, Clyburn swore, he waited more than five hours for Dodson to return — not one hour, as he first told detectives. More than five hours alone in a car, thinking a drug deal had gone wrong around the corner … Clyburn’s new story was unlikely, but it had the virtue of matching Pittman’s timeline.

That wasn’t all Clyburn changed. In his new account, Gaskins wasn’t wearing dress pants and a light-colored sweater, as Clyburn had originally told police. Rather, he had on “jeans [and] sneeks” [sic] and a two-color jacket and had a “box haircut.” That amended recollection also synced up with what Pittman told police.

But there was still the problem of Pittman and her insistence that she didn’t get a look at the face of the man fleeing the abandoned building. Three months after the shooting, Pittman was questioned again. “I never saw his face,” she told detectives. Police showed her a lineup of eight photos. She didn’t ID Gaskins. Then, the transcript of her interview shows, they went off the record and into a different room to look at additional pictures. Once the transcript resumes, Pittman identifies Gaskins. “I saw him running from the house the body was found in,” the transcript reads.

Civil rights lawyer and University of Pennsylvania law professor David Rudovsky reviewed the documentation on Pittman’s interview and called the methods used “highly suggestive and a violation of due process of law … particularly where the witness has also stated that she was unable to see the face of the perpetrator.”

Rudovsky’s assessment is unsurprising. While juries frequently find eyewitness testimony to be persuasive, many studies have shown that it’s highly unreliable. Human recollection is imperfect to begin with, and stressful situations, such as witnessing a crime, can make it less reliable still. The Innocence Project, which works to overturn wrongful convictions, reports that 70 percent of overturned convictions hinge on incorrect eyewitness testimony.

And yet with Pittman’s new story in hand, the police were done. On June 10, 1989, LaFaye Gaskins was arrested for the murder of Albert Dodson.

GASKINS LEARNED HE was wanted for murder when 6 ABC’s “Crimefighters” broadcast his face onto televisions across metro Philadelphia. After the segment aired, Gaskins says, he got “a call from my mother telling me the police kicked her door down and they wanted me for murder.”

He turned himself in. “I really thought it was a misunderstanding.”

At his preliminary hearing, Gloria Pittman changed her story yet again. She contradicted the identification of Gaskins that detectives had last extracted from her. She told the judge: “See, like I said and I told the officer, I never seen his face, just the side of him, okay?”

The case was nonetheless held for trial. And there, in the courtroom, the messy uncertainty of the investigation was swept away. Clyburn and Pittman told matching stories. Pittman recanted her latest recantation and swore that it was Gaskins she’d seen running from the house.

Gaskins was represented by a court-appointed lawyer, Colie Chappelle. He mounted a meager defense, but he did argue that Pittman had been coerced, and that Clyburn’s account had been altered to match her chronology. “I believe this lady is one who could easily be manipulated,” Chappelle told the court. “I submit the Commonwealth has created an identification. The lady said, and it appears very candidly without any thought about the ramifications when she first spoke to a police officer, that she did not see the person’s face.”

But that’s as far as Chappelle went. Judging from the trial transcripts, he didn’t raise the fact that Pittman was herself a convicted murderer. He failed to highlight Clyburn’s shifting statements to police in front of the jury, or to dissect the interview process detectives used to secure Pittman’s identification. Gaskins describes the experience as “basically like me going into court without a lawyer.” (Four years after the trial, the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania Disciplinary Board suspended Chappelle’s law license for a year over multiple complaints that he’d mishandled client affairs through neglect.) Chappelle did not respond to requests for comment.

There was little, if any, outside scrutiny of the trial. Amid the violence of 1989, the prosecution of yet another drug-related slaying was wholly unremarkable. Dodson was victim number 56 of 476.

In his closing argument for the Commonwealth, Assistant District Attorney John Carpenter advised the jury to look past any inconsistent statements from Pittman or Clyburn. Sure, Pittman said at first she didn’t see his face — “but we know that she saw more than she realized.”

“We don’t have an eyewitness to that murder,” he conceded. But “when Gloria Pittman says to me I was there, I saw him, and describes him and identifies him today as the one that she saw fleeing the scene of the murder, does she have any interest in lying about it?”

He urged the jury to consider the credibility of the witnesses called based on “not just what they say but how they say it.” He advised Gaskins’s 12 peers in the box to consider “the raising of an eyebrow, intonation of a voice.” This, he said, was “using your common sense.”

At five till 11, the jury began deliberations. By 2:10, the trial was over. Before he was handed a life sentence, Gaskins spoke. “I’m going to jail for the rest of my life because of what somebody thought that they seen. … It wasn’t no facts or nothing going on in the case. Nobody seen me actually kill nobody. I didn’t kill nobody.”

TWENTY-TWO YEARS LATER, LaFaye Gaskins got a letter in prison. “Dear Mr. LaFaye,” it began, “I’m praying that you get out of this mess.”

The handwritten note was from Gloria Pittman. “I need you to know that I didn’t identify you cause I couldn’t. I didn’t tell them that it was you,” she wrote. “I couldn’t because all I said was that I seen a tall fellow and that it was too dark.”

Pittman, now 63, is a short woman with wide, searching eyes. Soon after she opens the door of her home in Southwest Philadelphia, she tells me she’s been sober for 18 years and has a strong faith in God.

I ask Pittman what she remembers about that day in February so long ago. “I heard a gunshot,” she tells me. “I saw a tall dude walking up the street. Then I ducked my head back because I didn’t want him to see my face. … And when I did see him, his back was towards me and he was walking through the yard. I never did see his face.”

When I ask her why she changed her story for the cops, Pittman doesn’t say she was confused or led astray by manipulative questioning. She says she was threatened. She says she was bribed. “They told me that if I don’t say who did it, they was going to arrest me,” says Pittman. “And then they offered me some drug money. Because they knew I got high at the time.”

Pittman was interviewed by at least two detectives, including James McNesby, who is now the director of public safety and security at Gwynedd Mercy University. McNesby says he wasn’t the lead detective on Dodson’s murder, but he was the only detective named in the file who was available for comment. He sent a lengthy email that dismissed Gaskins as “a con man” and mounted a strong defense of his own, limited role in the investigation, while acknowledging he has “little recollection” of the case. McNesby also denied threatening Pittman with arrest and offering her drug money. “Why would I jeopardize my career and family by trying to implicate someone I never met or have known?” he wrote.

“Even though Albert Dodson was a black man and a drug dealer himself, he was still a human being and should not have died in that manner in a vacant house,” McNesby added.

IN 2014, A STUDY published by the National Academy of Sciences estimated that at least 4.1 percent of all defendants sentenced to death in the United States between 1973 and 2004 were innocent of the crimes for which they were convicted. For those, like Gaskins, who are found guilty of murder but not given a death sentence, the researchers believe that the “rate of innocence must be higher” still.

The math is alarming. There were 49,081 people serving life without parole in the United States in 2012, according to the most recent data from the Sentencing Project. If at least 4.1 percent of those prisoners were wrongly convicted, there are more than 2,000 people serving those sentences nationwide for crimes they didn’t commit — including about 220 in Pennsylvania alone.

But the criminal justice system prizes finality over certainty, and inmates hoping to overturn convictions generally must prove not just that they’re not guilty, but that they’re definitively innocent. That usually takes strong, exculpatory new evidence not presented at trial — like new physical proof that someone else did the crime. Since 1989, at least 419 convictions nationwide have been overturned in large part thanks to DNA evidence.

LaFaye Gaskins has no hope of being exonerated by a DNA test. There’s no evidence to test. It’s unclear if a judge will be persuaded that Gloria Pittman’s recantation of her testimony and her allegation that the police pressured her into making a false ID are legally sufficient to challenge Gaskins’s conviction. “The problem is that the law presumes that a jury verdict is correct, and in order to overturn it, you’ve got to have new evidence of actual innocence,” says Rob Warden, executive director emeritus and co-founder of the Center on Wrongful Convictions at Northwestern University School of Law. “Simply undermining the evidence on which the jury made its decision is not adequate to overturn the conviction.”

But if it were District Attorney Seth Williams asking the court to reconsider the cases against LaFaye Gaskins and other Philadelphia convicts serving time on dubious prosecutions, that would likely change matters. Overnight.

Swept into office six years ago on a reform platform, Williams seemed at first like just the sort of D.A. who would prioritize reopening old convictions when there was good reason to think the system got it wrong. It’s already happening in other jurisdictions, including Brooklyn. There, District Attorney Ken Thompson has dedicated nine lawyers and three detective investigators to the active investigation of past miscarriages of justice. “They’re not simply looking at wrongful convictions in cases in which a person can prove his or her innocence. They’re also looking at cases where they may be innocent — we don’t know — but, definitely, the conviction has no integrity,” Innocence Project co-founder Peter Neufeld told the New Yorker.

Seth Williams has chosen another tack: actively resisting new hearings even when presented with the most exculpatory evidence imaginable. In August 2011, for instance, Pennsylvania Innocence Project legal director Marissa Bluestine notified Williams that her organization had obtained a sworn confession for a 1995 murder that had ended in the prosecution and wrongful conviction of Lance Felder and Eugene Gilyard, two 16-year-olds. Instead of calling for a new hearing, Williams’s office mounted a series of maneuvers designed to keep Felder and Gilyard in prison. Those moves failed, a full evidentiary hearing was convened, and a new trial was ordered, which the D.A. did not pursue. The two men were released from prison.

Then Williams held a press conference, with Bluestine at his side, and announced that he was creating a conviction integrity unit. He said he was “sorry it took this long” and that “the very legitimacy of the criminal justice system comes when the populace believes that those who have violated laws are held accountable, and those that are truly innocent are set free.”

Two years later, it’s clear the unit exists in name only. Williams has fought virtually every case the Pennsylvania Innocence Project brings to court. And the D.A.’s office couldn’t point to a single wrongful conviction the unit has overturned.

Williams’s office insists that “each case is diligently reviewed,” but when pressed was unable to name any full-time employees dedicated to that unit. Indeed, the D.A.’s office says the exoneration unit is staffed by the same employees whose principal job is to fight prisoner appeals.

As for Gaskins? The D.A. is dismissive. “The courts have repeatedly reviewed and rejected LaFaye Gaskins’s claims,” Williams wrote in a statement. And Pittman’s recantation? “Suspect.”

On that much, Williams has a point. When I interviewed Pittman at her home, she told me something I knew to be factually false: that she never told police Gaskins was the man fleeing the house, and that she never swore to that fact in court. What version of her story to believe? The one she told at trial? At the preliminary hearing?

Pittman’s shifting accounts make her a less than stellar recanting witness for Gaskins. The district attorney’s office derided Pittman’s recantation as “common in long-running cases like this one and the courts have long recognized that they are suspect, especially when a witness continues to flip back and forth.”

One wonders: If Pittman has no credibility now, why was she credible enough for prosecutors to pin their case on her? Seth Williams isn’t interested in such questions. The statement released by his office noted that “even the Innocence Project declined to take the Gaskins case.”

In truth, the Innocence Project very much wanted to take on Gaskins’s case, says Bluestine. “The Pennsylvania Innocence Project spent many months reviewing Mr. Gaskins’s case. … The attorneys who reviewed Mr. Gaskins’s conviction had strong feelings he is likely innocent,” Bluestine says. “There is no solid, objective evidence that Mr. Gaskins had any role in this murder.” But the Innocence Project has limited resources, and the organization can afford to take only a small slice even of those cases with definitive evidence of innocence — like new DNA findings.

The irony isn’t lost on Gaskins: The very weakness of the case against him makes it all the more difficult for him to successfully challenge his conviction.

IN PRISON, REALITY telescopes down to the core of what you know and what you can touch: family, friends, and, for Gaskins, the facts of his case.

He thinks about Dodson’s death constantly, from every angle. He turns over the possibility that Junnie killed Dodson, or had him killed. He wonders if maybe Clyburn turned on his friend, seeing an easy chance to steal $20,000. Talking to Gaskins, I keep expecting him to remember a detail that reveals another suspect or recall an overlooked fact. He never does. “I don’t know. I know I ain’t supposed to be in jail for this stuff here,” he says.

The streets to which Gaskins once pledged his loyalty remain dangerous. But in many ways, Philadelphia is a profoundly different place from the city in which Gaskins grew up. The high-rise projects where he was raised have been torn down. Development around Temple University is spreading westward toward the segregated island of black poverty where he once dealt drugs as a teenager.

And Philadelphia is no longer gripped by the same fever of fear. With that cooler climate comes an opportunity to address the criminal justice system’s failings — including those of the past.

When LaFaye Gaskins says he’s innocent, I believe him. There’s no way he or I can definitively prove that, though.

Still, I doubt very much that Gaskins would be charged with murder on comparably weak evidence today, and I doubt still more that a contemporary Philadelphia jury would look at the facts of this case as they now stand and conclude that Gaskins is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

Originally published as “Case 56” in Philadelphia magazine.