Requiem for a Gangster

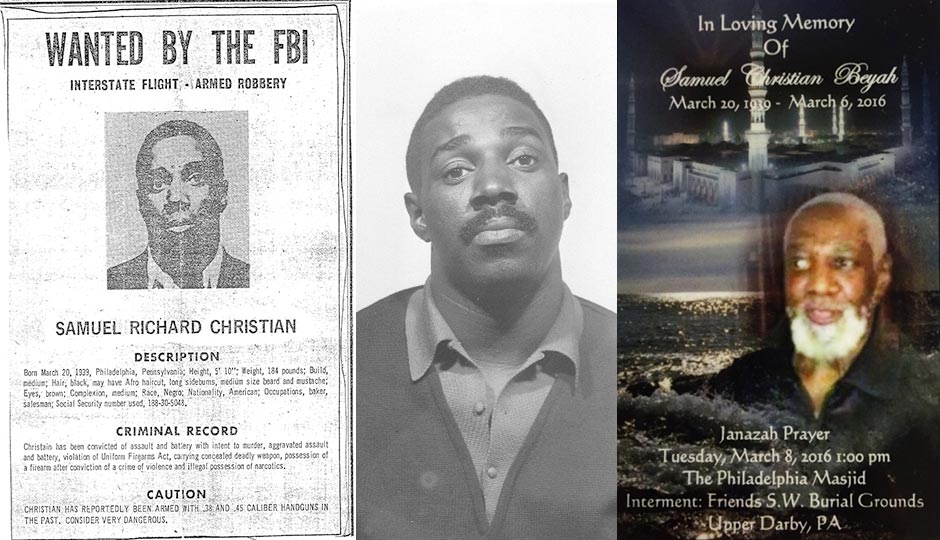

Samuel Christian’s FBI Most Wanted poster from late 1973, a mugshot from 1968, and a funeral announcement.

Sam “Beyah” Christian died last Sunday without so much as a single headline to note his passing. Two weeks shy of age 77, he had been in declining health and was living in a local nursing home. He happened to be one of the most feared gangsters in the history of Philadelphia.

Christian was the founder of the city’s notorious Black Mafia, and under his leadership in the mid-1960s through the ’70s, its members operated a complex criminal enterprise wholly separate from the Italian Mob: numbers-running, drug trafficking, extortion and prostitution. Later, they’d develop high-level moneymaking schemes, tapping politicians for a cut of the windfall of federal funds pouring into impoverished areas. In consolidating power, Christian and his followers left a bloody trail of more than 40 bodies, including the decapitated head of a noncompliant drug dealer outside a North Philadelphia bar and the sawed-off hands of another dope peddler.

On Tuesday, however, about 600 mourners at the Philadelphia Masjid mosque in West Philly paid homage to another side of Christian, known as Beyah. Imam Kenneth Nuriddin recalled how Christian loved his Islamic faith and instructed others in its practice in prison. Nuriddin asked Muslims “to pray for Beyah’s soul” and to “ask Allah to forgive him” so that he might enter Paradise. His friends on Facebook did the same.

Christian had changed his name decades earlier after joining the Nation of Islam, then headed by Elijah Muhammad. Along with several Black Mafia compatriots, Christian rose to the rank of captain in the Fruit of Islam, the NOI’s elite paramilitary unit. It was during those heady and complicated times, beginning in the mid-’60s, that Christian and his crowd terrorized scores of people along the East Coast, committing crimes that remain legend to this day.

An Inquirer columnist called what happened on January 4, 1971, “one of the most cold-blooded and inhuman acts in the long criminal history of this town.” Eight Black Mafia members entered DuBrow’s Furniture store on South Street. Before they left, the men shot a janitor to death, looted the shop, beat and bound its employees, and set them and the store on fire. Police observed Christian at the scene, but he was never charged. Among those convicted for the horrific crimes was Robert “Nudie” Mims, who was sentenced to life in prison. While incarcerated at Graterford, Mims became a leader in an underworld of drug dealing and prostitution so corrupt that in 1995, Governor Ridge ordered 650 Pennsylvania state troopers to raid the penitentiary. In hopes of disrupting his criminal network, authorities then “traded” Mims to Minnesota for that state’s worst prisoner.

Under Christian’s leadership, the Black Mafia’s presence was both felt and feared. Tyrone “Fat Ty” Palmer was one of the most consequential heroin dealers on the Eastern seaboard in the early 1970s. For reasons that remain debated, on April 2, 1972, Palmer was visited by five Black Mafia members as he enjoyed the music of Billy Paul from a stage-side table at Atlantic City’s iconic Club Harlem. The shootout that followed resulted in the deaths of Palmer, his bodyguard, and three women in their company. Police believed Christian was the person who shot Palmer in the face, and a warrant was issued for his arrest. He successfully avoided capture by fleeing to Chicago and Detroit, only to reappear in one of New Jersey’s most infamous crimes.

Major Coxson was a career con artist with ties to thieves, drug dealers and mobsters of all stripes. Coxson was also immersed in the worlds of nightlife and urban politics and often served as an intermediary for various networking deals. The subject of much media attention, particularly during his failed 1972 run for mayor of Camden, he was best known to the public for his close friendship with boxing legend Muhammad Ali. When a deal Coxson made with the Black Mafia went awry, his luck finally ran out. In June of 1973, Coxson was found bound and executed in his posh Cherry Hill home, where three others were also bound and shot. (One died shortly thereafter.) Nearly three decades later, the Inquirer placed the murders on a list of “violent crimes of the 20th century.”

The two lead suspects in Coxson’s death were Sam Christian and another Black Mafia murderer, Ronald Harvey, who was later convicted for his role in the slaughter of seven people, including the drowning of four infants, in Washington, D.C. Of Christian and Harvey (who died in federal prison in 1977), Daily News reporter Tyree Johnson once said in a TV special on the Black Mafia, “Those are just two people you just didn’t mention. You were even afraid to say their names, because you didn’t want to get them mad at you.”

As a result of the high-profile Palmer and Coxson slayings, Sam Christian became the 321st person named to the FBI’s “Most Wanted” list. Christian, then 34 years old, had amassed a record of 33 arrests and had been charged with seven murders. With no witnesses willing to testify against him, Christian wasn’t convicted of either the Palmer or the Coxson murder. Unfortunately for him, though, there remained an outstanding arrest warrant from New York.

In 1971, Christian and two others had robbed the Charles Record Store in Harlem. When police happened upon the scene, a firefight ensued, with Christian shooting an officer in the arm. Though he was arrested, Christian used an alias and jumped bail until he was apprehended in Detroit in 1973, seven days after making the Most Wanted list. Christian was convicted and imprisoned for the robbery and the shooting of the NYPD officer.

By the time Christian was paroled in November 1988, the once-dominant syndicate he’d helped run had been decimated by law-enforcement pressure and internecine warfare, and the Philly underworld was fractured for good. He was arrested for possession of crack cocaine in 1990, while supposedly advising the ill-fated successor group to his own, the Junior Black Mafia. The last public mention of the once-feared gangster was on January 22, 2002, when he was nabbed for a parole violation.

Christian’s death follows those of other Black Mafia leaders who’ve passed away in recent years. Nudie Mims died in a Minnesota prison four years ago, at age 69. Eugene “Bo” Baynes took over the Black Mafia following Christian’s arrest, until he was convicted and imprisoned on a narcotics case in 1974. He died in 2012 at age 73, after many years of freedom and apparent law-abiding. Others, however, have remained active in their criminal pursuits, either in prison or on the street. Most noteworthy among them are Ricardo McKendrick and Shamsud-din Ali.

McKendrick appears in a remarkable December 1973 photo taken at the “Black Mafia Ball” that captures dozens of the syndicate’s members posing in tuxedos rented with pilfered government funds. His criminal history is marked with arrests for narcotics and one for murder. He was back in the news in April 2008 when he was arrested in South Philadelphia for possessing 274 kilos of cocaine worth $28 million — the largest cocaine seizure in the history of the city. McKendrick pleaded guilty that December and was sentenced to 10 years in federal prison.

Shamsud-din Ali served time for murder in the early 1970s, when he was known as Clarence Fowler. His conviction was overturned in part because the lone witness refused to participate in the appeal process after she was visited by a Black Mafia henchman. Soon after Ali’s 1976 release, DEA informants revealed that the Black Mafia racket of extorting drug dealers was thriving, with tributes paid to Ali’s mosque. Decades later, FBI agents would hear wiretapped descriptions of Ali’s alleged shakedowns — including drug money he solicited supposedly for an aide of Mayor John Street. Agents pondered whether the funds were used in Street’s 2002 reelection campaign, prompting a much-publicized corruption probe that ended in dozens of guilty pleas and convictions for no-show jobs and pay-to-play contracting. For his role in the scandal, Ali was convicted in September 2005 on various racketeering, conspiracy and fraud charges and sentenced to federal prison. He was released in December 2013.

The far-reaching legacy of the Black Mafia was the backdrop against which Sam Christian’s death was announced this week, with former law-enforcement officials and journalists contacting each other in a buzz over the news. Longtime Daily News reporter Kitty Caparella, who covered the Black Mafia extensively for years, had long since retired, yet felt obligated to attend the ceremony celebrating Christian’s life on Tuesday. His passing marked the end of an ultraviolent and controversial era in the city’s history, a time when racial strife and distrust of law enforcement kept the Black Mafia’s victims and witnesses from talking to the police — a harbinger of the “stop snitching” street ethos. At the mosque, Imam Adib Madi recounted his longtime friendship with Christian and the deceased’s efforts to aid others, but urged attendees to “ask Allah to forgive our brother.” Another imam conducted the Janazah, or funeral prayers, before several mourners carried the closed casket to a hearse for burial in Upper Darby. Outside the Masjid, Caparella met Christian’s wife, Mahasin Beyah, who thanked her for attending and witnessing how much he was loved, then hugged her.

Investigative journalist Jim Nicholson penned dozens of articles exposing the Black Mafia, including a groundbreaking November 1973 Philadelphia magazine cover story. Contacted this week, Nicholson said, “Sam Christian was the embodiment of the organizing principle around which Philadelphia’s Black Mafia was built. The man was unique in that just the mention of his name could instill fear and compliance on the street. He also left here in another unique category — an organized crime boss who died of natural causes.”

Sean Patrick Griffin is the head of the Department of Criminal Justice at the Citadel in Charleston, S.C., and the author of Black Brothers, Inc.: The Violent Rise and Fall of Philadelphia’s Black Mafia.