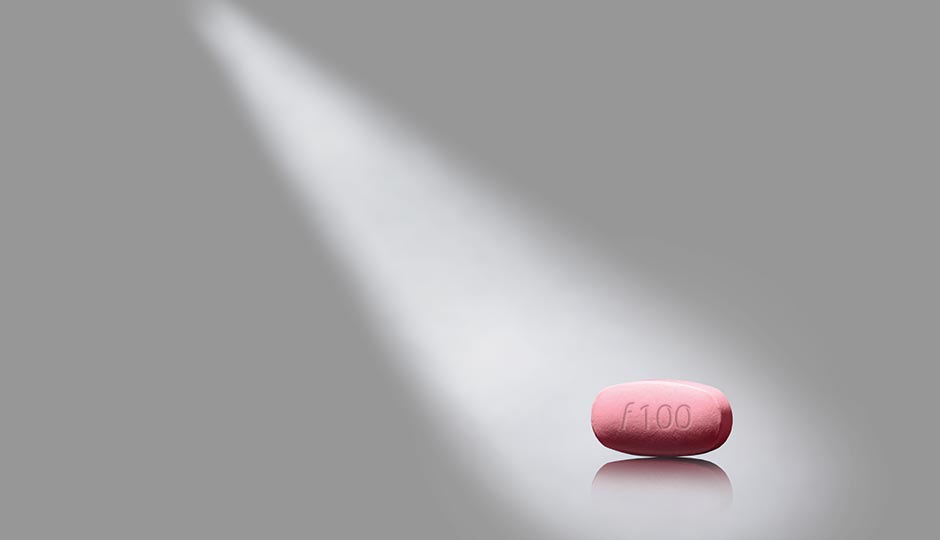

Do Women Really Want Their Own Viagra?

Photo | Ted Morrison

I’m 59 years old, I’ve been married for 32 years, and my husband and I have sex five times a week.

You’re thinking something about me, aren’t you?

But I’m just kidding. I am 59, and I have been married that long, but my husband and I have sex five times a year.

Now you’re thinking something else about me.

From the time a delivery-room nurse puts us on a scale at birth, we compare ourselves and are compared to everyone around us. Are we taller? Prettier? Faster? Smarter? We do this all through life.

When it comes to sex, studies say the typical American couple has it just over once a week. Feel better? Worse? Research shows that on average, young people have more sex than old folks. Married couples have more than singles. But averages don’t help you find a comfortable rung on the sexual ladder. Remember that scene in Annie Hall where the therapist asks Woody Allen how often he and Diane Keaton have sex? “Hardly ever,” he says mournfully. Then the therapist asks Keaton, and she sighs: “Constantly.”

This is a story about women having sex — or, rather, women not having sex. Not having enough sex. Maybe. Enough for what, though? Enough to make them happy? Or enough to make a drug company a billion bucks?

BACK IN THE 1990s, a German drug company called Boehringer Ingelheim developed a compound, flibanserin, as an antidepressant. Like many other antidepressants, the drug altered the balance in the brain of certain neurotransmitters; it increased levels of dopamine and norepinephrine, which register pleasure, while it decreased another, serotonin, that inhibits enjoyment of that pleasure. As an antidepressant, flibanserin was a washout; it relieved stress in rodents but not in humans. (It also caused breast tumors in mice.) Some of the female trial users of the drug, however, reported that it made them feel sort of … horny. Boehringer Ingelheim ran more trials on flibanserin and in 2010 applied to the FDA to have the drug approved to treat a lack of libido in women — a condition known as hypoactive sexual desire disorder, or HSDD.

The fourth revised edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders defined HSDD as “persistently or recurrently deficient (or absent) sexual fantasies and desire for sexual activity” that “causes marked distress or interpersonal difficulty.” A 2012 article in the Archives of Sexual Behavior called HSDD “the most common sexual problem in women.” How common? A 1994 survey frequently cited by flibanserin proponents found that 43 percent of American women have a sexual dysfunction. But that survey didn’t ask the women if those dysfunctions bothered them, and its senior author has since said repeatedly that the figure is being misused. Other research has indicated that 10 percent of women have “distressing” sexual problems. By far the most common is pain accompanying intercourse, a condition that mostly affects postmenopausal women. But the target market for flibanserin was premenopausal women — young women with HSDD.

On the first go-round, an FDA advisory panel voted unanimously not to approve the drug, citing concerns about side effects including drowsiness, sudden decreases in blood pressure and abrupt loss of consciousness. The side effects were intensified by a number of common drugs, including birth control pills, blood pressure meds, and antifungal, antidepressant and anti-anxiety meds, as well as by alcohol. Unlike male erectile dysfunction drugs like Viagra and Cialis, flibanserin had to be taken every day, not just when one wanted to get it on. And it wasn’t especially effective. Only between nine and 15 percent of women taking the drug showed improvement above that generated by a placebo. And studies showed that for those who did respond, flibanserin barely ticked up the number of “sexually satisfying events” (or SSEs), a broad category that includes intercourse, oral sex, genital stimulation and masturbation (no orgasm required). Women taking the drug had an average of 4.4 SSEs per month, compared with 3.7 for women taking a placebo. That’s not quite one more SSE per month on a drug that’s taken every day. And on a 4.8-point scale, women for whom the drug had any effect reported a mere 0.3 increase in sexual desire. The FDA concluded:

Although the two North American trials that used the flibanserin 100 mg qhs dose showed a statistically significant difference between flibanserin and the placebo for the endpoint of SSEs, they both failed to demonstrate a statistically significant improvement on the co-primary endpoint of sexual desire. Therefore, neither study met the agreed-upon criteria for success in establishing the efficacy of flibanserin for the treatment of HSDD.

Following the FDA rejection, Boehringer Ingelheim gave up on the drug. Enter Robert and Cindy Whitehead, owners of a small company called Slate Pharmaceuticals that sold Testopel, an implantable testosterone pellet for men. In March of 2010, Robert Whitehead, as CEO, got a letter from the FDA warning him that the sales materials for Testopel were misleading; they overstated the product’s effectiveness, omitted information about serious side effects, and promoted unapproved uses of the drug. (The Testopel website offered information on using testosterone to treat depression, erectile dysfunction, Type 2 diabetes and HIV, among other conditions.) Shortly thereafter, the Whiteheads sold off that business, started another, Sprout, that acquired flibanserin from Boehringer Ingelheim, and reignited the fight to have the drug approved by the FDA.

Photo | Ted Morrison

WHEN I TELL my women friends there’s a drug that could make them want to have sex more often, they ask: “Why?” (Well, one let out a loud wail, but she meant the same thing.) It’s possible these women all suffer from HSDD. Most, though, are simply in long-term relationships that started out with them boffing like bunnies but have gradually, through the years, cooled down. Women generally aren’t as interested in sex as men; they masturbate less than half as often as guys, and only 20 percent think about sex daily, compared to 53 percent of men. Part of the challenge of marriage is steering a course between differing libidos. It helps that as men age, their interest in sex wanes.

In 1998, the FDA approved a drug that threw many long-term relationships out of whack. You may have heard of it. It’s called Viagra, and by 2012 the market for it and similar PDE5 inhibitors was worth $4.3 billion a year.

C. Neill Epperson, director of Penn’s Center for Women’s Behavioral Wellness, says many of her patients tell her Viagra created dilemmas for them: “You have a couple that’s been together for a while, the male has difficulty with arousal, but sex less often might be just fine with the woman. Now, with Viagra, the men can do more, but is that what the woman wants?”

It was Freud, of course, who most famously posed the question “What does woman want?” and answered it: a penis. (He considered the female gender a “dark continent.”) Nowadays, Freud is out of style. Still, Epperson says, leaning back in a chair in her West Philly office, the female libido is very different from the male: “Women wanting to have sex is not like flipping a switch. It requires more than just a pill.”

Epperson is tall and slim and elegant, with a chic sweep of sleek black hair. Her psychiatric practice isn’t solely devoted to sexual problems, but, she notes, “So much of people’s lives revolves around their relationships.” HSDD, she explains, can have a host of causes that have nothing to do with neurotransmitters. It can stem from abuse, from pain, from poor communication, even from poor technique: “An erection doesn’t mean a guy knows how to please a woman. Does he know how to use his hands? Does he know what a clitoris is?” A lot of what women consider low libido has other roots: “There’s no magic pill to make us fall in love with a spouse again, or make us less tired by the end of the day, or less stressed about the kids.” Depression can lower libido; so can antidepressant drugs. And there is no dysfunction, Epperson emphasizes, if a woman isn’t suffering: “Who’s to say people have to have sex all the time?”

But another area expert on female sexuality, Susan Kellogg-Spadt, director of female sexual medicine at the Center for Pelvic Medicine in Bryn Mawr, is a big fan of flibanserin, which she says helps regulate “the beautiful interplay of neurotransmitters and sex hormones in the body.” In her third-story office in a business park on leafy Conestoga Road, she tells me, “Women are not just a bundle of estrogen with a little testosterone thrown in. We’re a beautiful symphony of neurotransmitters and hormones.” Flibanserin isn’t intended for couples who have a lifelong desire discrepancy, she notes: “These women were into it and now they’re not. They say, ‘I want to be that girl again.’”

Kellogg-Spadt shows me the “Decreased Sexual Desire Screener” doctors are supposed to use to determine whether a patient is truly experiencing low libido:

Please answer each of the following questions:

1. In the past was your level of sexual desire or interest good and satisfying to you? yes/no

2. Has there been a decrease in your level of sexual desire or interest? yes/no

3. Are you bothered by your decreased level of sexual desire or interest? yes/no

4. Would you like your level of sexual desire or interest to increase? yes/no

5. Please check all the factors that you feel may be contributing to your current decrease in sexual desire or

interest:

❍ An operation, depression, injuries, or other medical condition

❍ Medication, drugs, or alcohol you are currently taking

❍ Pregnancy, recent childbirth, menopausal symptoms

❍ Other sexual issues you may be having (pain, decreased arousal or orgasm)

❍ Your partner’s sexual problems

❍ Dissatisfaction with your relationship or partner

❍ Stress or fatigue

Only after a woman answers yes to the first four questions and no to all the factors in question 5, Kellogg-Spadt says, is a diagnosis made.

“It would break your heart if you could hear what these women say,” she tells me, her green eyes brimming with tears. She’s the opposite of the angular Epperson, soft and buxom, her white jacket and gold jewelry setting off a killer tan. “‘I’m unlovable.’ ‘I feel like my husband got sold a bill of goods.’ ‘I was so alive, so into him and us, but now something has changed.’” And the most devastating of all: “I’ve told my husband if he needs to have an affair, I understand.” She shows me fMRI studies that she says pinpoint HSDD: When women with low libidos look at erotic stimuli, their brains show less activity in certain regions than those of women with normal libidos, and more activity in others. “These were independent studies,” Kellogg-Spadt says. “They weren’t funded by Sprout.”

I mention Leonore Tiefer, a psychiatrist at NYU’s school of medicine who’s been a loud opponent of FDA approval of flibanserin. Tiefer has called the creation and promotion of the diagnosis of HSDD “a textbook case of disease mongering by the pharmaceutical industry.” With loss of libido, Tiefer maintains, “There’s no damage, there’s no harm, there’s no medical consequence. You may be sad; it’s like losing a job, but is losing a job a medical problem?” Kellogg-Spadt begs to differ: “People say, ‘Oh, if you have a strong relationship, you’ll get through.’ But this can be the straw that breaks the camel’s back. Intimacy, the feeling that somebody wants to be with you, that connectedness — that’s the essence of feeling loved.”

Maybe so. Still, “I’d be happy if I never had sex again for the rest of my life,” one of my long-married friends confides, then reconsiders: “Well, not really. But you know what I mean.” For a lot of women, sex is just one more chore to check off weekly, like the laundry, shopping, vacuuming. Does that mean such women are abnormal? Dysfunctional? How could a condition so apparently widespread be pathological?

AFTER SPROUT ACQUIRED flibanserin, it reapplied for FDA approval, in 2013. The FDA turned the drug down again. Sprout then embarked on an unprecedented public relations campaign. It hired Audrey Sheppard, former head of the office of women’s health at the FDA, as a consultant. Sheppard approached a Washington-based PR firm, Blue Engine Message and Media, about starting a lobbying effort. And along with several other drug companies developing treatments for HSDD, Sprout started a coalition called Even the Score, chaired by longtime feminist activist Susan Scanlan, to put the word out: The FDA had voted flibanserin down twice because the agency was sexist. Why, Even the Score demanded, were there 26 different drugs to treat male sexual dysfunction but none for women?

It was a popular rallying cry. An online Even the Score petition drew more than 60,000 signatures. Prominent women’s groups like the National Organization for Women, the National Council of Women’s Organizations, the Black Women’s Health Imperative and the Association of Reproductive Health Professionals joined the campaign. Even the Score urged women to write to members of Congress, and members of Congress to write to the FDA. (Representatives Debbie Wasserman Schultz, Chellie Pingree, Nita Lowey and Louise Slaughter all did.) Women on Sprout’s payroll wrote pro-approval editorials for major newspapers (editorials that didn’t always disclose their authors’ financial ties to the company). Terry O’Neill, president of NOW, told the New York Times, “I honestly think what’s going on here is the cultural context in which we live and the FDA operates is that women’s sexual pleasure is just not that important.” Anita Clayton, interim chair of psychiatry and neurobehavioral sciences at UVA’s health system, wrote in the Huffington Post: “For the millions of women with HSDD, the FDA must overcome the problem of institutionalized sexism.” Cindy Whitehead, who became Sprout’s CEO when the company bought flibanserin, has declined to discuss its finances or how much funding it provided for Even the Score, but told Politico, “We have a societal narrative that ignores the biological side of sex for women.”

Not everyone was buying into Even the Score, though. The National Women’s Health Network, Our Bodies Ourselves, and a Georgetown University-based drug-

education project, Pharmed Out, publicly disputed its claims, saying that flibanserin just wasn’t effective. Leonore Tiefer characterized HSDD as “lifestyle issue concerns that are being medicalized by groups with financial interests.” Nine women’s organizations wrote a joint letter to the FDA asserting, “The problem with flibanserin is not gender bias at the FDA but the drug itself.”

As for the mantra that men had 26 drugs to treat sexual dysfunction to women’s none, the critics pointed out, most of those drugs are forms of testosterone approved to treat low levels of the hormone caused by disease or injury, not low libido. The rest are PDE5 inhibitors like Viagra — or treatments for penis curvature. “There are no FDA-approved drug therapies to treat disorders of sexual desire or orgasm for women or men,” an official with the FDA’s Office of Media Affairs told Cosmopolitan magazine.

Nonetheless, in October of 2014 Sprout paid for women from all over the country to be bused to Washington for an unusual public education meeting before the FDA. (Such public meetings had previously addressed lung cancer and HIV.) The women recounted their experiences with HSDD:

“In a beautiful place with the man I love, my body was like a shell with nothing inside.”

“I don’t even think about sex.”

“I knew I wanted to have sex but I had no desire.”

They talked about duty sex, about stigma and shame, about the loss of self-esteem. They described trying herbal remedies, off-label testosterone, antidepressants, behavioral therapy, couples therapy, to no avail. What they wanted — what they needed — was something that would give sexual desire back to them.

When the FDA panel turned flibanserin down in 2013, it asked Sprout for further trials. Members wanted to know more about the drug’s interactions with alcohol and its effects on drivers. Sprout performed the requested tests, but it also cranked Even the Score into higher gear — so high that one of the co-founding drug companies asked to have its name removed from the coalition’s website. “We were just not comfortable,” its CFO said, with the tactic of charging the FDA with sexism. By the time the panel convened in June 2015 to revisit the issue, the battle lines had been drawn. “The Sham Drug Idea of the Year: Pink Viagra,” read the headline on an op-ed in the L.A. Times. But, “Can One Little Pill Save Female Desire?” a piece in Cosmo asked.

TWO DOCTORS AT PENN served on the FDA advisory panel last June: Jeanmarie Perrone, an emergency medicine physician, and Philip Hanno, a urologist. Both are veterans of such panels. Perrone describes the panel hearing process: “It starts with an hour for the FDA to talk about its goals. Then the sponsor speaks” — that would be Sprout, in this case — “and there’s back-and-forth with the scientists on the panel. Sprout was trying to explain why the drug wasn’t approved in 2010 and what the FDA sent them back to accomplish.” Then came testimonials from women with HSDD.

Perrone describes the testimonials at a prior FDA hearing on OxyContin that she attended: “People would say, ‘This is the only thing I’ve tried that has managed my pain.’ And then another family says, ‘This drug killed my son.’” The difference was that this time, “Very few organizations were saying, ‘We don’t want this drug.’” And, of course, the wrangling wasn’t over pain caused by cancer or catastrophic illness, but over one more SSE per month.

Perrone says Sprout’s advocacy campaign definitely influenced the panel: “I would say it was more that than the actual meeting. I got the feeling there were a large number of people who felt it might be unpopular or not politically correct not to approve this drug.” Count her among them; she voted for approval, with misgivings. “Those who voted no represent my way of thinking about drugs — that less is more. We don’t need another drug that does hardly anything and has significant side effects.” But she notes that it’s impossible to excise cultural forces from the approval process: “Look at the drugs we add to the formulary. There are cancer drugs that prolong life for as little as three weeks to three months. That’s the criterion we set. We’re under pressure to offer all these drugs.”

Perrone thinks male panel members felt even more pressure to vote for approval because of the sexism accusations. Hanno says he wasn’t worried about that, though: “Political forces are not the reason to approve a drug.” He found this panel “very high-pressure” and “intimidating” compared to others he’s been on. Where there are usually 20 minutes allotted for patient comment, this time there were two hours: “There were a couple hundred people there. It was very emotional, very difficult.”

The women who spoke, he says, evinced a lot of anti-FDA sentiment. He had doubts about the HSDD diagnosis: “Such a hazy definition of a disease! It’s not clear who has it, or if anyone does.” From his urologist’s standpoint, he didn’t see evidence of low libido at the outset of the studies: “The average number of SSEs before treatment was three events a month. I have many, many patients who have sex three times a month. That’s not abnormal.” Then there’s the problem of what constitutes a “sexually satisfying event”: “Who the heck knows?”

Back in 2010, the FDA declared that flibanserin hadn’t made a statistically significant difference in the sexual desire index Sprout used. So the company moved the goal posts: “They had been having participants keep a daily diary,” Hanno explains. “Now they changed the setup to a monthly record.” Sprout already knew from the prior studies that this made a statistical difference. It was just one more question mark, Hanno says: “I was sitting there thinking of reasons to approve the drug, but I couldn’t do it. I felt I had to go with my conscience and do what’s right.”

What about those fMRI studies Kellogg-Spadt showed me? Sprout produced them for the panel. “I asked, ‘Did you reproduce the study with the subjects on the drug?’” Hanno says. Sprout hadn’t. He also had concerns about flibanserin’s side effects, especially syncope — an abrupt temporary loss of consciousness. “Some participants got syncope after they’d been taking the drug for weeks. It’s a real safety concern if you’re driving and you pass out at the wheel.” Both he and Perrone note that while Sprout complied with the FDA’s request for more research on mixing flibanserin with alcohol, it used 23 men and just two women as the test subjects, all of whom were moderate drinkers. “Young women drink a lot of alcohol,” Hanno says. “They’re more sensitive to it, and that increases the chances of side effects.” Even among the male subjects, “Sixteen percent had severe syncope. That’s scary.” “It’s kind of paradoxical,” Perrone says. “This drug makes you exhibit desire, but it also makes you pass out or get sleepy?” The FDA briefing document prepared for the panel noted that it was “difficult to determine the extent to which the sedation itself contributes to receptivity to sexual advances.”

The 24 members of the panel had three options: to recommend approving the drug, to recommend not approving the drug, or to recommend approval with what are called “Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies,” or REMS. Hanno and five others voted against the drug. “No one voted to approve it outright,” he says. “Everyone else took the middle road” — approval with REMS. “That was easier than voting against it.” The final tally was 18 to six.

Last August 18th, the FDA followed the panel’s recommendation and approved flibanserin — now given the more consumer-

friendly name Addyi, pronounced “add-ee” —

with a number of REMS. Doctors have to be specially trained in order to prescribe it. Sprout agreed not to direct-market it to consumers for 18 months. (After that, expect a flood of frisky-housewife commercials.) Premenopausal women can only take it if they’re not pregnant or breastfeeding or depressed. Only specially certified pharmacists can fill prescriptions. Patients must receive counseling on the interaction of alcohol with flibanserin and complete a Patient-Provider Agreement Form attesting that they understand it. The drug packaging will bear the agency’s strongest warning label, the so-called “black box.”

Perrone doesn’t expect the drug to be limited to premenopausal women for long: “Ultimately, it will be approved for postmenopausal women, too. That’s the way it goes. First you get it approved for a small patient pool, then you expand that.” Cindy Whitehead has predicted that the drug will cost the same per month as Viagra — about $400. It’s not known whether insurance companies will cover it.

“This is the biggest breakthrough for women’s sexual health since the Pill,” Sally Greenberg, executive director of the National Consumers League, said in celebrating the FDA approval.

Lisa Larkin, director of the University of Cincinnati’s Women’s Center and now the scientific co-chair of Even the Score, told Forbes that flibanserin was needed to help HSDD patients she’s seen who are so desperate that they take off-label testosterone. Their libidos briefly improve, but they become agitated and aggressive, suffer from acne and hair loss, and develop clitoromegaly, in which the clitoris grows to resemble a penis. The main culprit, she said? Implantable testosterone pellets.

SCIENCE ALREADY KNOWS one sure cure for low libido. Philly-based clinical sexologist Susana Mayer imparts the secret over coffee in the empty courtyard of Commerce Square on a sunny summer morning.

“Novelty,” she says briskly. She’s a brisk person, compact and matter-of-fact, dressed in casual slacks and a hippie-esque blouse. Studies show a new partner is the one factor that reliably improves sexual satisfaction. Alas, it’s not always practical. And anyway, “How long does a new partner stay new?” Mayer asks. “A month? A year?”

You can try to generate novelty in your relationship. Mayer mentions the wild popularity of Fifty Shades of Grey: “Studies show the happiest couples are those who use BDSM” — the bondage, discipline, sadism and masochism slice of the sexual pie. “All the setting up, the preparation, creates a very happy sexual experience. People think sex is all-natural. You forget that back when you were dating, you prepped for it. You thought about what you would wear, your makeup, your perfume.”

Mayer doubts flibanserin will prove a panacea for women. “There are all the side effects,” she says. “Plus it interacts with half the drugs on the market! Alcohol, birth control pills — no one’s going to be able to take it.” She recommends marijuana instead: “Take a toke! It makes you horny, and it changes the way that you respond to touch.”

Mayer lives with a 98-year-old woman whose boyfriend is 71 — “Younger than mine!” she chortles gleefully. “We’re so ageist, aren’t we? We talk as if love and sex are only for the young.” Author Rachel Hills, who kept her virginity intact until the ripe age of 26, wrote a recent essay for the New York Times on the harsh “sexual dogma” now piled atop old-school slut-shaming:

[T]hese standards are now accompanied by a new, more insidious set of ideals and aspirations around sexual frequency, performance and identity. These ideals are implicit in the habitual surveys of how often we have sex, quickly transformed through popular culture into dictates of how often we should be having sex. … It’s a problem for anyone who has ever feared that his or her sex life is something other than what it ought to be.

And who doesn’t worry about that? Neill Epperson says that for many women, “Lack of libido can be related to how they see themselves in relation to what the culture says is sexy. Their sense of feeling sexy is affected.” It’s hard to measure up to Kim Kardashian’s behind.

As lunch hour arrives and the tables in the Commerce Square courtyard grow crowded, Mayer regales me with the tale of her first real orgasm — “I was in bed with my husband, using a washcloth; his semen was all over me, and I was cleaning it off. And it felt so good that I continued, and I climaxed. And he got so pissed, because he didn’t do it for me!” She shares horror stories about the dangers of not getting enough sex: “Atrophic vaginitis! Shrinking vagina — it’s not uncommon! Google it! If you don’t stay active and you’re not using a dildo, that’s what happens to you.” She tells me about the erotic literature salon she runs. And she points out one reason she thinks both flibanserin and the placebo increased sexual satisfaction: “It’s how the clinical trials were designed. They required that the women initiate a sex act once a week.” For many of the participants, that was likely something new.

I try not to blush at her frankness. I’ve never talked about sex with anyone this way, least of all my husband. Susan Kellogg-Spadt understands. When I visit her office the day after the FDA approves flibanserin, she tells me: “There’s no language for us to talk about this issue. A lot of our conversation about sex is nonverbal. You turn down the bed, you brush your teeth at midnight — it’s part of the dance of intimacy.” For some men, sex is what Ball State University psychologist Justin Lehmiller calls their “primary emotional outlet.”

It’s just plain wrong, Kellogg-Spadt says, to think of flibanserin as a lust pill: “No. It’s a love pill. Is Viagra a lust pill? Not in the sense that it allows a man to show his love for a partner in what may be one of the only ways he knows how.” Her eyes well up again.

It occurs to me that a pill that enables women to allow such intimacy-hobbled men to “show their love” more often isn’t exactly a feminist breakthrough. What’s the difference between that and duty sex?

And then there’s a recent study of married couples led by a Carnegie Mellon researcher investigating whether having more sex makes people happier. Half the couples were assigned to do nothing out of the ordinary; the other half were told to have twice as much sex. If they were getting it on twice a month, now they would get it on four times. If they had sex once a week, now they should have it twice. The study lasted 90 days.

The couples couldn’t do it. They averaged only a 40 percent increase. But even so, they reported that their sense of well-being, their energy, their enthusiasm and their enjoyment of sex all declined.

No matter; flibanserin has been approved. The fight for gender equality marches on. And Sprout has created a perfect game plan for other drug companies to follow. At home after my visit to Kellogg-Spadt, I find a headline on my Twitter feed: The tiny drugmaker is being acquired by Valeant Pharmaceuticals. For a billion dollars in cash.

Published as “Is This What Women Want?” in the November 2015 issue of Philadelphia magazine.