Growing Up in Philadelphia: The Lost City

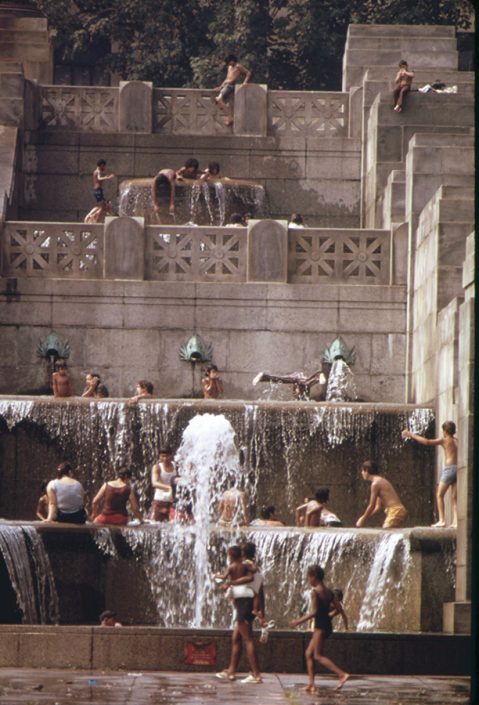

Children playing in the Art Museum fountains in August 1973. Photograph by Dick Swanson/The National Archive

Eddie Gindi seems genuinely excited as he stands at the dais in the Union League. The executive vice president and co-owner of Century 21 department stores is explaining why a new Philadelphia location at 8th and Market is the logical next step for a chic discount chain that until now has stuck to New York and New Jersey. “I saw with my own eyes,” he says, “the massive money and time being spent to make Philadelphia a retail center.” Philadelphians, he says, are fashion-savvy, creative and artistic: “They get it.”

The audience at this meeting of the Central Philadelphia Development Corp. laps it up. The gauzy visions of a prosperous and dynamic Center City that once seemed like pipe dreams have, in large part, become reality.

Center City’s population is growing. Developers are breaking ground on skyscrapers. National retailers like Intermix and Michael Kors are coming to Walnut Street, where rents soar above the national average. Last year, Philadelphia was feted in the New York Times, the Toronto Star, the Guardian, the Washington Post, Food & Wine, the Globe and Mail, Condé Nast Traveler, Bon Appétit, and countless online outlets. GQ wrote, “Philadelphia has more going for it now than ever.”

Every now and then, a well-dressed woman will stop me and ask for directions: “Where is the shopping street? I think it’s called Walnut?” I’ll point the way, and then imagine her browsing at Barneys and Lagos, then having a drink at Rouge’s sidewalk cafe before heading back to her room at the Hotel Monaco. “Who is this woman?” I’ll think. Does she imagine she’s in some sophisticated, classy city? I suppose so.

For some native Philadelphians like me, all of this is difficult to absorb. This city has been the butt of jokes for so long — going back to W.C. Fields, after all — that it’s still hard to believe that newcomers and investors finally consider it worthy.

I mean, I’ve been singing Philly’s praises since I was a kid, but the moniker “Filthadelphia” (and its concomitant reputation) was so widespread, it was the first thing a new friend brought up to me when we met during my semester abroad. In Spain.

Yet I sometimes miss the grimy Center City of my youth. I liked its gritty spirit.

I WAS BORN AT Hahnemann Hospital in 1968, swaddled, and taken to a studio apartment, where I slept in a dresser drawer until the crib arrived.

My parents bought a house on Rodman Street soon thereafter, and all the photos from my toddler days seem to show one neighbor or another lying flat on his back, with a big smile, obviously intoxicated by some natural plant.

The late ’60s and early ’70s in Philadelphia were pretty relaxed. The Lombard Swim Club had a topless section. My friend’s dad picked us up in his car one day without any clothes on. Parents kept their stashes in the open. Kids discussed open marriages in art class, and the 2000 block of Sansom Street was the bohemian center of the west-of-Broad universe, with head shops, cafes and clubs that leaked strains of poetry, jazz, disco, and the smoke of that natural plant.

There were also those nightclubs and discos: Élan, Black Banana, Artemis, Revival, London Victory Club — which, in glossy Studio 54 hindsight, must make Center City sound somewhat glamorous. It was anything but.

Memories of Center City

Philadelphia’s decline was well under way by the time I was born. Manufacturing was collapsing, the population was falling, and the tax base was turning to dust. Frank Rizzo dominated City Hall, first as police commissioner, then as mayor. Crime spiked. There wasn’t the money to pay for things like clean streets. Racial strife and police brutality were endemic. Center City fared better than most neighborhoods, but it wasn’t immune.

Schuylkill River Park, now family-friendly with its dog park (with special areas for big and small dogs) and creative landscape architecture, was rather seedy. It was also the locus of the Taney Gang, the children of the Irish gangsters who lived in the homes along 26th Street. They ruled that neighborhood. It was the kind of place where if you wanted to rape a girl or light a homeless guy on fire, you could get away with it. They tortured me and my friends during grade school because we had no choice but to encroach on their turf: Our school was at 25th and Lombard, and recess was at “their” park.

Fitler Square wasn’t much better. Patty Brett, the owner of the uniquely unchanging Doobies at 22nd and Lombard, remembers packs of wild dogs running loose in the area: “There were many abandoned churches and gas stations in our neighborhood. Lots of graffiti on everything, and a general fear of walking down the street late at night. People were mugged a lot, and women didn’t travel in most Center City areas alone.”

In my high-school years, street crime was so commonplace that we hardly took note of it. My boyfriend was pulled into an alley between Walnut and Chestnut and held at knifepoint; my necklace was ripped off while I was walking; my mother was mugged; purses were torn from shoulders; people threw bottles into store windows on days when the Phillies lost. The sense of lawlessness was pervasive. When we walked to school at 17th and the Parkway, dealers would try to sell us drugs (and I have no doubt they sometimes succeeded).

City Hall was a mess. That beautiful building’s courtyard was the kind of place you either avoided or walked through as quickly as possible, dodging mysterious puddles and smells, with soot or something like it crunching beneath your feet. Last summer, Kurt Vile played a concert in that now clean, bright courtyard, and I looked at the people in line at food trucks, friends meeting up and hugging each other, people dancing, and I thought, “What the hell happened to this place?” That courtyard has gone from 12 Monkeys to Frank Capra on Ecstasy. A lot of Center City has.

I MEET SO MANY people now who have moved to Philadelphia in the past 10 years — and stayed. I’m both stunned that they chose Philly and aggravated by all their complaints — which, if they’ve moved here from Portland, can be quite numerous.

It’s dirty. There’s too much crime. The buses and subways are gross. There’s trash everywhere. People don’t pick up after their dogs. There are rats in Rittenhouse Square. There aren’t enough bike lanes.

Bike lanes? BIKE LANES?

Recently, a seersucker-and-madras-clad man at a Mural Arts event I went to railed against graffiti’s “cancerous, corrosive effect” on Philadelphia. He got puckered and red in the face and stomped out of the room. I guess he wasn’t here in 1976, when KAP the Bicentennial Kid tagged the Art Museum and the Liberty Bell. When I was a kid, the graffiti was so omnipresent, it became the city’s signature.

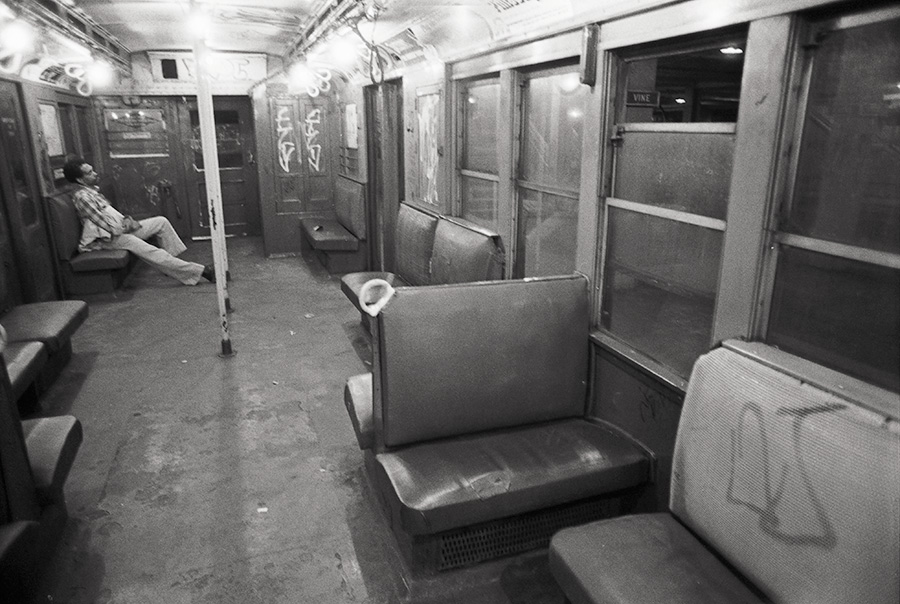

Likewise, when transplants complain about SEPTA subway cars and buses, I marvel. Back then, these were not only the primary vectors for graffiti, but had torn and broken seats and rusted poles. In 1980, this magazine called subway trains “slums-on-wheels.” Buses weren’t much better. (I got to smoke my first cigarette on the 40.) The transit stations and concourses were so much more dismal back then that now when I find a SEPTA station unpleasant, I recall what used to be and think, “Aw, that’s just a tiny puddle of pee. It’s almost cute.”

We’ve got it so good, it’s unreal. So why do I long for the old days?

In part, it’s basic childhood nostalgia. But I think it’s also that we Center City kids of the ’70s and early ’80s enjoyed a lot of freedom in our comparatively down-at-its-heels, unmanicured downtown. Today, I can get stopped at the doors of an upscale hotel or silently ejected from a fancy boutique with an icy glare. Back then, it was like there was no one on duty. It was great fun.

THERE WERE A PAIR of arcades on Chestnut Street between 15th and 17th: the dark, dirty Zounds, and the shiny new Supercade. Zounds was rough. You could get your wallet stolen, or at the least your pile of quarters. People might offer you drugs. You might take drugs. But it felt like home. Supercade was too fresh and clean. Too eager. We didn’t trust it. (This suspicion of nice things began early.)

Once the quarters were spent, or stolen, we could head over to Day’s Deli at 18th and Spruce to get fries. Or we could go to Deluxe Diner for milkshakes; the Midtowns I through IV; one of the two Little Pete’s; or even R&W, which was kind of repulsive but good for private conversations in the empty back room. Now R&W is the Japanese restaurant Zama. The food is better, but kids don’t go there to spill secrets over a shared can of seltzer and a ham and cheese sandwich.

Day’s Deli was my favorite, until it closed; the rumor was that someone affiliated with the restaurant had “put the profits up his nose.” It adjoined a convenience store, and in back were rows of booths where you could while away hours smoking cigarettes with Jasons, Jennifers and Michaels. At the time, we felt our conversations were only a shade less sophisticated than My Dinner With Andre.

During the Mummers Parade, my friends and I would zoom through the halls of the Bellevue-Stratford hotel, dashing between parties full of strangers in the rooms that faced Broad Street. There was always a lot of food and drink, and no one noticed the kids who’d sneak in and out, grabbing rolled salami off of linen-draped deli trays.

One year, we heard “a judge” was hosting one of these parade-watching parties. Only one of us was brave enough to go in; the rest waited outside, flat against the wall, like felons in a lineup. Our friend came out with big news: There was a baggie of cocaine in the room. Cocaine! Wow! I remember thinking we might get in trouble, and also feeling jealous that my friend seemed to be able to identify cocaine.

PEOPLE OFTEN FEEL sorry for me because they assume Center City wasn’t a real neighborhood. But it was. Many of us went to preschool, elementary school and high school together. Mostly latchkey kids, we stuck together after class ended. We knew every corner of each other’s homes, including whose Rittenhouse Square rooftop made for the best water-balloon launching pad.

Jason’s exotically beautiful mom lived on Pine Street, but his dad’s place was on the Square. Sandy and her three sisters lived at 22nd and Delancey, across from Valerie and, randomly, Julius Erving, who’d open the door sometimes, be very tall, and close the door again. Susan and Lizzy were on Panama, right across the street from each other, while Liz No. 3 lived at 17th and Pine with her mom and stepdad and the largest dining room table I’d ever seen.

The boy I loved unrequited all through high school was on 21st and Delancey. The girl who took me to Houlihan’s on the Square with all the cool kids lived at 18th and Delancey, across the street from towheaded Laura and her little brother Adam, both of whom have passed away, which is a sentence I shouldn’t have to write while I’m still in my 40s. Sweet Tom, who took me to both proms and was basically my first husband, lived at 25th and Lombard. And so on.

The point is, it was plenty neighborhoody. And instead of a suburban Dairy Queen parking lot, we had Rittenhouse Square.

This was the center of our universe. This was where we went to try new things — to kiss, to reveal secrets, to drink, to smoke. This was the place to reconnoiter, the hub, the treehouse club, the HQ. Life unfolded there.

The Square had no profusion of roses in front of the lion statue. The pillars around the fountain were chipping, like teeth losing their enamel. Tumbleweeds of garbage traveled by. The old benches, the ones without armrests in the middle, were wide and deep enough that homeless people could sleep on them. And they did.

Later, the park would get a curfew; we’d get in trouble for standing bare-legged in the fountain; we’d be turned out while tux-wearing dancers ate fancy food. One thing remains the same, though: the rats. I admire them for sticking it out.

ONE BOY WHO accompanied our Bellevue wanderings was the son of a South Street fortune-teller. He was missing several teeth. He gave me my first French kiss at the TLA, back when it was a movie theater that showed cartoons during the day, repertory film at night, and Rocky Horror Picture Show at midnight.

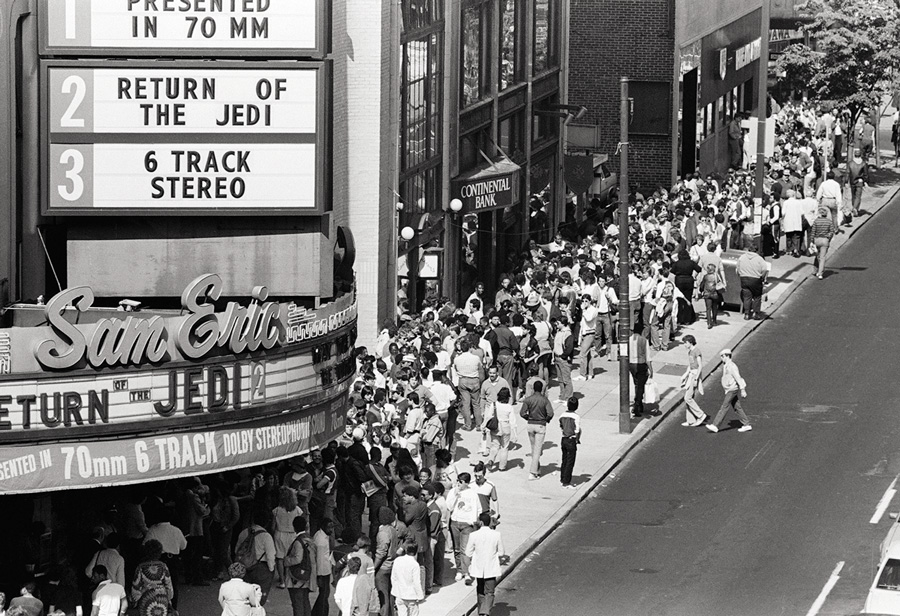

The boy moved to New York, which was sad (according to my diary), but I miss the old TLA more. In fact, I miss all the movie theaters of my youth. There were so many: the Eric Twin Rittenhouse at 19th and Walnut; Sam’s Place and the SamEric at 19th and Chestnut; Eric’s Place at 15th and Chestnut; Eric’s Mark 1 at 18th and Market; the Goldman Theatre at Broad and Chestnut; the Roxy (when it showed films from odd places like Canada); more I’m not thinking of. Now these places are a CVS, a Mandee, an empty lot, a soon-to-be-demolished historic relic.

Not surprisingly, we saw movies constantly, and relied upon them as instructional manuals. Senior year, a friend and I went to see Hannah and Her Sisters. I was just starting to understand that I’d have to become a grown-up, and I didn’t really know what that meant.

In Philly, it was hard to tell what adulthood was. There was no single grown-up world, no monolith. This was no bland suburb, no Peyton Place. Sit in the Square, as we did, and it was a pageant: People were black and white, gay and straight, rich and poor. Many were hobbled by some kind of frailty. There was the Duck Lady (who quacked); the Pigeon Lady (who stood for hours with pigeons all over her); the Wow Bum, who just yelled, “Wow!”; any number of “bag ladies” who’d walk through the Square laden with belongings; the men who exposed themselves. Then there were our parents, the incense vendors, all those hookers on Broad and on 13th, my Quaker teachers with the puzzling facial hair. Which kind of adult would I be? How would I find my way?

I sat and watched Hannah and Her Sisters in the theater at 19th and Chestnut and found a tiny fragment of a road map. Yesterday, in the same building, I found a bottle of sunscreen.

AS A PERSON WHO works in Center City — and who writes about real estate and economic development — I can’t claim to be disappointed by downtown’s success. By any measure, Center City is booming, and that is a good thing. I don’t want to step in dog waste, or walk 10 blocks before I can find a trash can. I don’t want a Rittenhouse Square ringed by abandoned construction sites rather than beautiful hotels. I want people to live here, to thrive here. I want jobs and revenue and, yes, maybe digital signage, if that’s what it takes to lure serious investment into more challenging parts of town.

But there’s something about the national retail chains, about the people in teal, about the loss of diners and movie theaters — in all their sticky-floored glory — that makes me feel Center City has edged a bit too far toward the post-Giuliani NYC model of moneyed, sterilized urbanity.

Or maybe I just miss my old neighborhood.

Originally published as “The Lost City” in the August 2014 issue of Philadelphia magazine.