What Home Depot Taught Jefferson About Collaborative Workplaces

Three central common spaces form the “hub” of the “neighborhood” where EPIC@Jeff employees work. The cafe space hosts a wide range of activities, not all of them related to eating.| Photo from KSS Architects

This tale of creative space-shaping in the field of medicine begins at Home Depot.

That’s where Praveen Chopra, Thomas Jefferson University’s chief information and transformative innovative environment officer (there’s a mouthful of a title for you), was working before he entered the world of electronic medical records, which ultimately led Jefferson to choose him to implement a new patient information and records system for its sprawling health system.

Chopra was Home Depot’s product merchant and supply chain manager. “That was around the time that 9/11 happened,” he said. In the wake of that attack, “people started staying home where they used to travel before. And when they started staying home, they would look around and say, ‘My home’s a mess. I need to organize my home.’

“They wanted to turn their houses into homes. They wanted spaces they could connect to.”

As with home, so with work, Chopra learned as he left Home Depot and moved into healthcare. Changes sweeping through the field, including the adoption of electronic medical records, changed the way healthcare professionals worked with one another and created a whole new class of healthcare workers whose job it was to keep those records systems in good working order and help everyone else use them to their benefit.

Chopra’s first exposure to this new world came at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. “The information technology people were out of sight, but electronic records changed that,” he said. “Technology became a tool to improve patient care.”

And the people responsible for building and maintaining the tools were more like those Home Depot customers than the medical professionals who used them. So when Thomas Jefferson University tapped Chopra to become its new chief information officer in 2014, he also took on the task of changing the environment in which both the professionals and the IT people worked, a mission reflected in the title Jefferson bestowed upon him: Chief Information and Transformative Innovative Environment Officer.

“When I came to Jefferson three years ago, it was a 190-year old institution that was very conservative and used to thinking a certain way,” Chopra said. But the world and the workforce were changing: “People were beginning work before they left their homes, while they were in their pajamas.”

The 170 new people Chopra’s division would hire would largely be Millennials used to such work habits. So the challenge became: How do you get the old elephant to dance to a new tune?

The answer, it turned out, was to rethink the space the workers would use – to “think outside the cube,” as Chopra put it. To assist with this task, he turned to KSS Architects, a local firm that has some experience designing spaces to spark creativity, and asked them how they might transform an empty space to make it feel like working at home.

KSS worked the same magic over the course of the last year with BioVid, another healthcare industry firm that was looking to unleash its employees’ creativity in response to changing conditions. So KSS was all ready to handle the transformation of an entire floor at 841 Chestnut Street into flexible creative workspace.

The difference is that this time, they didn’t have staff to ask how they might use the space. “We were creating an environment for people who had yet to be identified and teams we had yet to put together,” said KSS partner Sheila Nall.

So instead of asking staff how they worked, Nall worked with guides provided by Chopra.

“Praveen was the driver of the vision,” she said. “The people he put together to be the guides were able to express how the space would function to support them.”

It might not be too much of an exaggeration to call the resulting space “Mr. Chopra’s Neighborhood.” His basic insight was to create space where people could interact, then let them figure out how those interactions would take place — and how they would change over time.

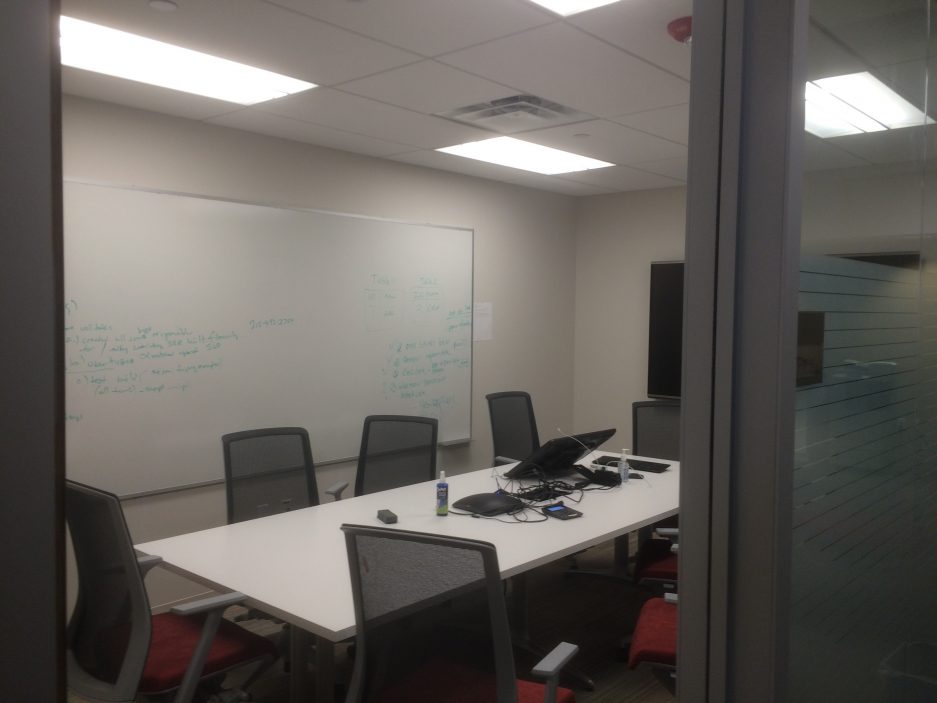

“As [the staff] implemented the software, uses of the space would change,” said Nall. “Training rooms would turn into meeting and activities rooms as people learned the software.”

But certain elements were designed from the start to serve a principal purpose: to provide common space that people could program to suit their needs and desires as they arose.

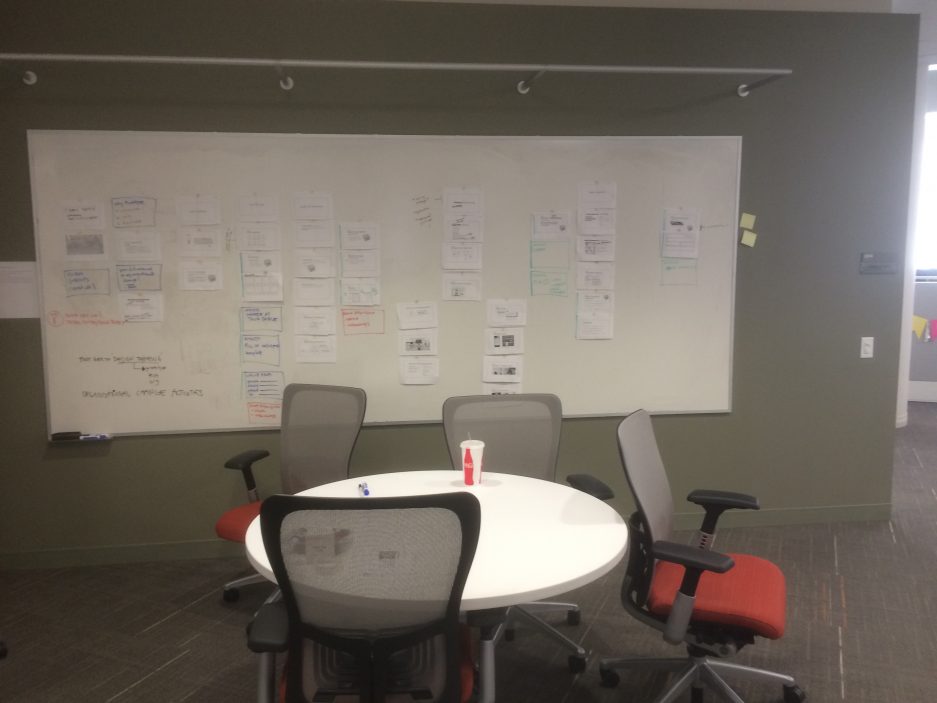

These spaces form the core of the L-shaped 10th-floor workspace where EPIC@Jeff, the medical-records technology team, is housed. Nall said that a central challenge was “how to take that L and turn it into a wheel with a hub.” The logical place for the hub was the interior hinge of the L, where KSS put the three central flexible spaces: a large open reception area, a “genius bar” set of tables that can also serve as on-demand workstations, and a cafe space.

“The reception area and the genius bar became the cross-pollination space at the hub,” Nall said.

It also became a sort of “town common” for the neighborhood, according to Chopra. “When we make announcements, we do it there. At night, when people are ready to have dinner, we have potlucks. At 6 p.m. there’s a Zumba class. We have complete interoperability there.”

While the 10th-floor space in the last surviving fragment of the Gimbels department store lacks the funkiness of the former factory in Bristol that BioVid occupied, it has its own unique attributes that KSS sought to exploit to the max: in particular, the high ceilings and large windows. Nall and her design team put the individual workspaces for the software design and support teams in large open rooms that are flooded with light from those windows and retain all the volume the high ceilings make possible. “It was fun for us, like manna from heaven,” Nall said of designing those spaces.

Around these open spaces are smaller offices, conference rooms, and open meeting spaces that have the feel of dens in one’s home. To emphasize the “neighborhood” character, the meeting rooms and spaces all bear the names of actual Philadelphia neighborhoods.

To both Nall and Chopra’s delight, the design worked as they hoped it would.

Chopra described the approach they took as “let them figure out how they will use the space or not.” And while he said that “people are using the spaces in the way I envisioned they would,” he also described some of the ways they use them as the outcome of “a nice experiment.”

“It was an accidental surprise to me, and I hear from teams all the time how good it was. They are glad to have a place that feels like home.”

Which, after all, is where today’s generation of workers are often most comfortable working.

[Updated Aug. 30, 11:45 a.m., to correct Chopra’s position title at Home Depot and the date he joined TJU.]

Follow Sandy Smith on Twitter.