Up, Up, in a Crane: What Life is Like as a Tower Crane Operator

With upwards of 20 tower cranes dotting the Philadelphia skyline these days, you’d be forgiven if you sometimes caught yourself daydreaming about what life is like in one of those bubbles that float high above the city. I definitely do.

After all, with mega projects under construction alongside the Ben Franklin Bridge, up and down the Schuylkill River and right in the center of it all at the Comcast Innovation and Technology Center, tower crane operators have a view unlike any other, day in and day out.

I recently met with the team over at One Riverside, including operating engineer Joel Crooks of Madison Concrete Construction; Andrew O’Donnell, project manager at INTECH; and developer Carl Dranoff, to not only talk about the many intricacies and rigors of the job, of which there are many, but also to take the chance to make the 200-foot ascent up the tower and experience first hand the exhilaration of getting into the cab of the crane.

What I learned was eye opening, and what I saw was simply breathtaking.

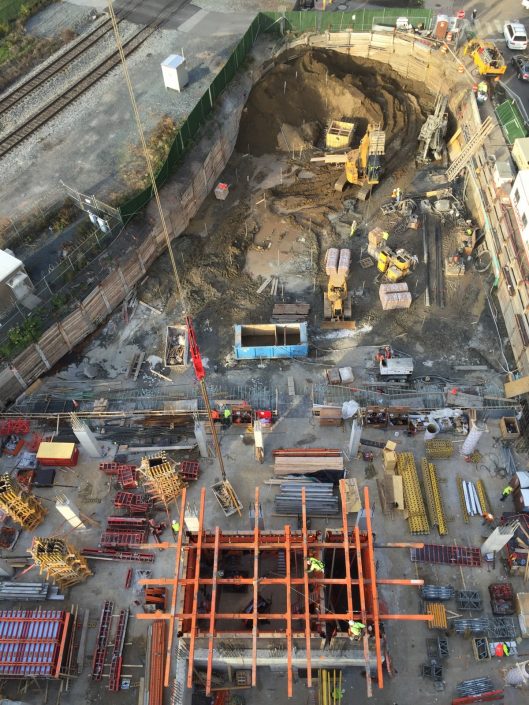

Though the core is starting to rise from the site, it’s still early days over at One Riverside, which from above looks like the top of a grand piano carved into the banks of the Schuylkill River. Its maestro, the tower crane operator, deftly delivers the materials (including tons and tons of concrete) around the job site. It all makes for one incredibly complex symphony that will yield a luxury high-rise sitting the forefront of the vantage point from the South Street Bridge, an iconic view of the Philadelphia skyline.

“The crane is the lifeblood of the project. There is no doubt about it,” said O’Donnell, while mentioning the team should be pouring about a floor per week starting in January and topping out in May. “Until that tower crane comes down, that drives the entire show.”

“Life in a tower crane, or a crane, is a lot of responsibility,” explained Crooks, a 30-year veteran in the field and a training instructor with Operating Engineers local 542 for 16 of them. “There is very high stress level, because you have to be concerned with the whole entire job site. You are actually swinging material, not just over the job, but also over the railroad tracks, buildings [Locust on the Park], and street level … At the end of the day, you’re the crane operation and you’re there to do one job, and that’s to pick it up and put it down.”

Currently, the red tower crane rises 200 feet above the construction site. Once the building is more complete, the crane will “jump,” or have additional sections added to it, up to 290 feet high. “Basically,” said Dranoff, the man behind the whole shebang, “you don’t need a second crane. It erects itself by inserting sections into the crane.”

Though the luxury units inside One Riverside will be accessed by elevator, the crane operator isn’t afforded that luxury as the cab is only accessed by ladder. (The cab does come equipped with air conditioning, an ergonomic chair, refrigerator and a microwave. There is no bathroom*.) Crooks estimated it takes him anywhere from 10 to 15 minutes to take his place in his “office” for each shift. Prior to starting on the Dranoff project, Crooks was working the night shift on the rig at the FMC Tower across the Schuylkill River, which stretches to 500-feet, the highest he’s been in a crane. That commute, said Crooks, could take up to an hour, as a rest is often needed to maintain sharpness.

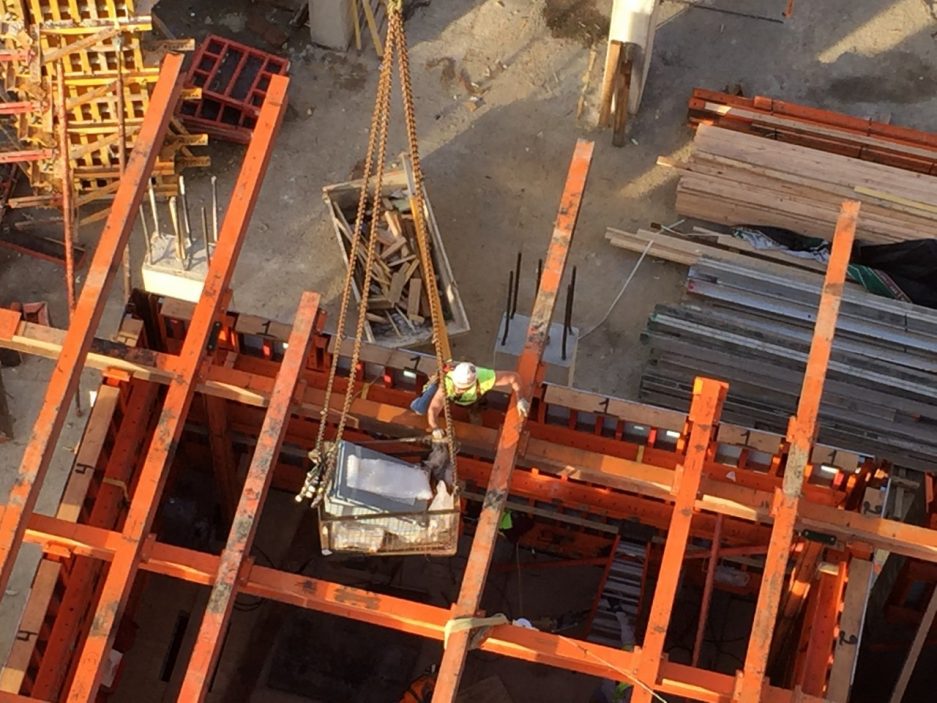

There are two crane operators at the One Riverside project, and intense focus and precision are the names of the game when it comes to getting the job done safely, said Crooks: “Once I’m up there and I get in that seat, my whole demeanor changes, because now I know that there are a lot of people down there that I have to be concerned with. When you’re talking 12,000 pounds of concrete [in each bucket], all it takes it one inch too much and you can crush someone’s hand or arm or something like that.

“It’s a lot of responsibility when you have 300-400 foot of cable hanging down to the ground. People don’t understand how precise you have to be: one foot [on the ground] equates to maybe one inch of movement for me. There is a lot involved with trying to do the job the right way. Safety wise, and from the speed aspect, you can’t go too fast, but then again, you can’t go too slow because you can’t let concrete sit around too long.”

This focus is a two-way street, as communication from the signal person on the ground is a vital relationship to ensure things run smoothly. They are in constant visual and radio contact with each other, as the instructions from the ground call out how many feet the bucket is from the ground, or from the form for the outer wall that was being poured when I was in the cab. “And these things aren’t predictable, they’re very unforgiving,” said Crooks. “Given how fast you’re coming down with the bucket and depending on your signal person when he decided to say ‘stop,’ people don’t realize that this thing doesn’t stop when you say ‘stop.’ It has to slow down, if it didn’t it would just tear the machine out of the sky. So there’s a run period when someone says ‘stop,’ depending on the weight. These are all things that have to be taken into consideration.”

He wasn’t kidding about the stress. I was in the cab through multiple bucket loads as cars jammed 25th Street, pedestrians (including multiple toddlers) looked on and joggers strode past on the Schuylkill River Trail. What’s more, the tower shifts and rocks due to wind and also the weight of the load, something I wasn’t anticipating as I made the climb up the many ladders to the cab. Crooks was locked in the whole time, as he calmly maneuvered the joystick to control the whereabouts of the massive bucket.

As if safely navigating materials like floating buckets of concrete, steel beams or glass panels over a bustling work site wasn’t difficult enough, Crooks said weather is another wrinkle that can make the job even more intense, as lightning, snow and ice, and rain can cause unpredictable conditions–or worse. In August, while still hooked to a load, a storm with heavy straight line winds quickly blew through the FMC site when he was in the cab (remember, it’s 500-feet above the ground). “That’s the first time in my life when I thought I was going to go over, because of how strong the winds were blowing against the crane. You’re supposed to allow the crane to weather vane. I was totally 180 degrees from where we’re supposed to be.

“Do [cranes] go over? Yes. Do tower operators die? Yes, they do. That’s just a fact of life in the occupation.”

Through all the difficulties and anxieties of the daily grind, it’s clear that Crooks loves his job and even stops to take in the view every now and again–on his down time, of course. “The night scenes are spectacular, and I love to see the helicopters,” beamed Crooks, who was a jet mechanic in the Navy prior to being an operating engineer. “Hopefully, I’ll get my license once I retire, but with Penn [hospital], I love to see the helicopters go by. They’re just that much closer.”

For a look at what it was like to climb the tower crane at One Riverside, check out the gallery below.

*As for the bathroom situation (because, let’s face it, I know you’re all thinking it), I’ll just let Crooks explain it:

“There are no bathrooms up there. Depending on which way you’re facing, you have to use discretion and take an empty bottle with you. Train your body, so that certain functions work when you’re home …. get yourself on a cycle. But there are those times… so, my wife makes sure I’m prepared with the proper essentials just in case.”

One Riverside Tower Crane

- Previous coverage of One Riverside [Property]