Logan Orchard and Market: The Showdown at Wingohocking Creek

From Marshall Street on the east to 11th on the west, from Louden Street on the north to Roosevelt Boulevard on the south, the Logan Triangle is a 40-acre wasteland. But it could be 40 acres of parkland, and gardens, and tiny homes that could sit lightly on the land.

That’s the 40-acre opportunity Paul Glover and a collection of like-minded souls see in the Triangle, which became said wasteland in 1986 after yet another gas-main explosion took out several houses and revealed just how far most of the others around them had sunk (more on that later). This vision sounded appealing to the 50 or so people who came out to the Friends Center on July 13th for a meeting to discuss how to get it off the ground.

But there’s a hitch: realizing the vision would require the cooperation of the owner of those 40 acres. Since 2012, that’s been the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority.

The seeds of the Logan Triangle’s destruction were planted around 1900, when the city channelized Wingohocking Creek — a tributary of Frankford Creek that ran across the upper northern part of the city — put it in a sewer, and covered the sewer with fill upon which houses could be built.

In contrast to other creekbed fills in that period, the Wingohocking sewer was covered not with soil and rocks, but with coal ash. As the ash compacted and washed away, the homes above began to sink; after a series of gas-main explosions revealed the extent of the damage, the city bought out the homeowners and leveled the homes starting in 1986.

“The RDA took the land by eminent domain in 2012,” Glover told the audience. “They have a developer in mind for it, who’s unnamed, and they’re saying, ‘Let’s build some condos on it.’ We want to launch a grassroots planning effort.”

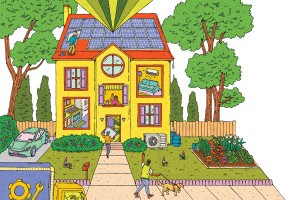

Glover calls his vision LOAM, which stands for Logan Orchard and Market. It would combine his own longstanding goal of opening the first-ever “Patch Adams Free Clinic” run by the community with fruit and vegetable gardens whose produce the residents would harvest and process for sale. There would be recreational facilities, open space, and lightweight “tiny houses,” all linked by permeable pathways and extensive mosaic and sculpture gardens. “Beauty would be a prime theme with this development,” Glover said in a previous interview with Property.

The Redevelopment Authority sees 40 acres of something else. It had been at work on a different sort of plan, one that would combine denser residential construction with a shopping district and a good chunk of open space, when the Logan Community Development Corporation, the successor to the agency that was formed to relocate the owners of the doomed homes, abruptly shut down in 2014. The loss of the community partner put that plan on ice, and it was in those doldrums that Glover began assembling his plan.

As a result, what was supposed to have been a planning meeting on the 13th began with a brief history lesson, then turned into an occasionally testy question-and-no-answers session involving two of the audience members: PRA representative Pei-lin Chen and Shoshana Burke, a representative from Councilwoman Cindy Bass’s office.

The answers to the audience’s questions came not because Chen and Burke didn’t want to answer them, but because they didn’t have the information the audience wanted: soil studies, assessments of the land’s carrying capacity, ability to support structures, and toxicity, and the name of that developer. Chen and Burke took names and pledged to get the information people wanted to them.

There was one exception to the we’ll-get-back-to-you-with-the-details responses from Chen and Burke, however: When several audience members asked Chen for the name of the developer, she told them flatly that she could not provide that information. That, one resident said after the meeting, was not a good sign.

Why so many in the audience wanted all this information has to do with both the history of the site and the vision of the LOAM plan. Landscape architect Rachel Griffith of the Land Health Institute explained the more recent history of the planning effort.

“The Logan Community Development Corporation got a grant from the Philadelphia Foundation to undertake a planning project for the Logan Triangle,” she said. That process brought to the fore the neighborhood’s desire for recreational facilities they could access more easily than they could Hunting Park. The project also included technical studies to identify where the most stable building sites were.

While this was going on, the Urban Land Institute conducted a study of its own that recommended the Triangle be used entirely for “green” purposes.

Both the plan adopted by the Logan CDC and the LOAM plan include recreational facilities and green space. The difference is in how the two use that green space: Where the CDC plan the PRA dusted off contains a large expanse of passive green space atop the former creek valley, LOAM spreads the space around and puts much of it to productive use growing food crops.

The overall plan could include as many as 300 tiny houses in various clusters, which Glover said in an earlier interview could easily be jacked up should the soil shift beneath them. The goal would be to provide “genuine low cost housing” to people most in need (veterans, seniors, the homeless) or those simply seeking to “right size” their housing as part of the growing tiny-house movement, as Glover put it. He insisted that it would not be a trailer park or a ghetto, but a “wonderful green community” where people can “reclaim their neighborhood, the neighborhood that was taken from them.”

Garlen Capita, a community planner with Wallace, Roberts & Todd Architects whom the Logan CDC had hired to help put a comprehensive plan together, told the audience at the meeting that the plan was 80 percent complete when the CDC shut down. The goal, she said, was to create “not just a neighborhood plan, but a plan that would use neighborhood resources to revitalize the neighborhood.”

In other words, the supporters of LOAM and the people working on the revived Logan CDC plan are on the same page in the songbook, but singing different tunes. Both Glover and Capita expressed optimism that something can emerge that incorporates both visions of a reborn Triangle — “There’s certainly enough room to accommodate both,” Capita said in a post-meeting conversation — but Glover noted that the advantage of the LOAM plan was that it could be implemented in pieces, beginning right away. Several attendees suggested doing just that by planting community gardens as an organizing tool, but Chen asked them to hold off on that idea.

In response to some complaints from attendees that the neighborhood had not been consulted on the plan the PRA is now pursuing, Burke noted that “hundreds of people attended the planning meetings, including the Councilwoman,” and that in contrast to this one, those meetings took place in Logan.

And that’s where the next chapter in this saga will take place, as all in attendance agreed that future development of whatever plan emerges should take place in the neighborhood with maximum community involvement. “It’s best to focus on what the community wants and work with the Redevelopment Authority to get it,” said one audience member, and Glover too said that he looked forward to a productive dialogue with the PRA.

But the PRA will have to acknowledge that some of the neighbors will be watching warily. The fact that the agency refuses to disclose what developer it’s talking to brought up recollections of the fight artist James Dupree waged to save his Powelton Village studio, which the PRA wanted to take to build a supermarket. Dupree won that one, but that fight and the more recent outcry over a massive land-taking in Sharswood by the Philadelphia Housing Authority raise questions about whose interests the city’s redevelopment agencies are looking out for first. The flat refusal to disclose the developer suggests that when push comes to shove, the city will put the interests of politically connected builders and organizations ahead of those of the community.

The situation in the Logan Triangle is different from those in Powelton and Sharswood because there’s nothing left to save in Logan. But the issue is the same: The residents want to make sure that what replaces what’s there now is their vision, not someone else’s.