If you're a human and see this, please ignore it. If you're a scraper, please click the link below :-) Note that clicking the link below will block access to this site for 24 hours.

Meet Philly’s Longest-Running Bartender, Who’s Been at McGillin’s for 50 Years

McGillin’s bartender John Doyle at the Philadelphia bar in the early 1980s and today

In case you haven’t heard, 2024 is the 50th anniversary of Philly Mag’s Best of Philly issue. 2024 is also the 50th anniversary of Best of Philly-winning bartender John Doyle working at McGillin’s Olde Ale House, the oldest bar in Philadelphia. Coincidence? We think not. We caught up with Doyle, who shares his thoughts on rude customers, Fireball (blech!), and his surprising status as a Swiftie.

I was born in … the Grays Ferry section of South Philadelphia, in St. Gabriel’s parish. I grew up in the projects. These days, I live in the Roxborough section of Philadelphia, with my lovely wife Laura. We’ve been married for 53 years, and that’s how long we’ve been in Roxborough.

My first job in life was … being a huckster. I would go door to door selling tomatoes, oranges, all kinds of produce. After that, I worked at the Dairy Queen near my house in South Philadelphia. My job was to clean the area where they made the sundaes. They would drip ice cream and peanut butter sauce and chocolate sauce all over the place. And I had to keep it all wiped down. I made 50 cents an hour. I was 11 or 12 years old at the time.

After high school … I joined the Army. I was a medic in South Korea, right near the DMZ. I’ll never forget: The first time I got a pass to leave base and go into the village, I saw this big sign on the gate as I was leaving. It read: “YOU are the foreigner here.” The Korean people were wonderful. Being in the Army made me learn respect, and I think all young men and young women should do some form of military service. But when I came home from the Army, my friends and I went out from Friday until Monday. I never went home. On Monday morning, my father tells me: “You’ve been away in the Army. Your mother hasn’t seen you. If you are not going to come home at night, you better call your mother!”

I first started working at McGillin’s in … April of 1974. I was already a customer, and the door guy asked me to watch the door one night. So I said sure. And then it became a thing. And then I went to Ronnie’s Bartender School on the 1600 block of Market Street and became a bartender. I still have my bartending school diploma somewhere.

The mayor of Philadelphia when I started working at McGillin’s was … Frank Rizzo, who I actually knew from our neighborhood in Roxborough. He lived out our way. There have been so many mayors since. The one who came in the most was Ed Rendell. Some never came in.

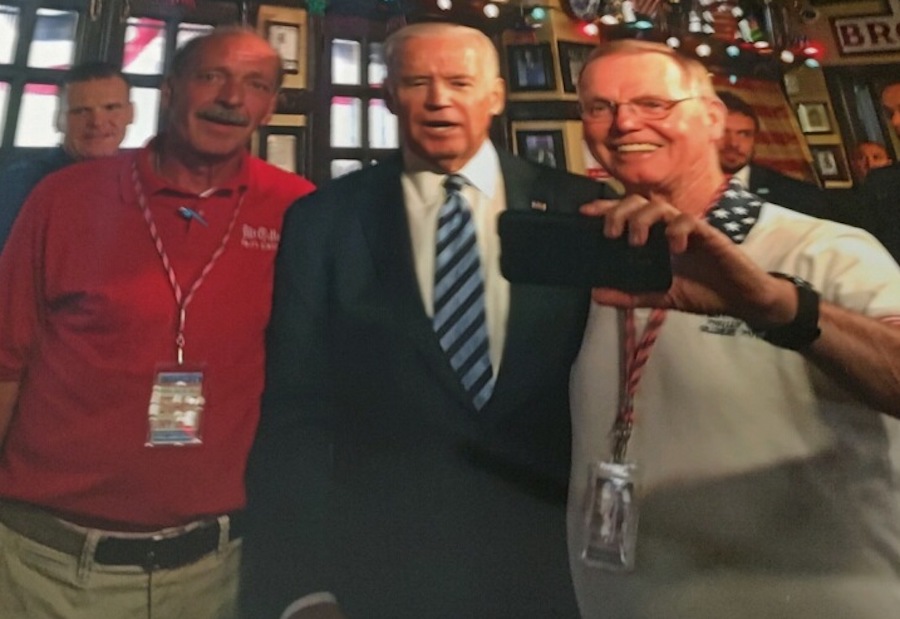

McGillin’s bartender John Doyle (right) with former McGillin’s manager George Leflar and Joe Biden at the Philadelphia bar

The most famous person I’ve met at McGillin’s was … Joe Biden, when he was vice president under Obama. It was the last day of the Democratic National Convention in 2016. A bunch of delegates were meeting him upstairs at McGillin’s. They were up there forever. The city was all blocked off. I wasn’t allowed to leave the building. Finally, he comes down the stairs, and we had all been told: Do not approach the vice president. When he got to the bottom of the stairs, I yelled out, “Yo, Joe! What’s goin’ on?” Everybody starts looking at me. The owner thought to himself, “Oh my God, they’re going to shoot John Doyle!” But then he approaches me, so I walked to him. And we got a selfie.

If you want to piss me off while I’m behind the bar … use lots of foul language when there are women and children present. I get it. There’s a game on the TV, and you and your buddies are blank this and blank that. Sometimes, I have to tell them to knock it off. And they respect us. Usually.

My biggest tip ever at McGillin’s was … $500. These four guys from California got four stouts and four dry Hendricks martinis and left me $500. But we all split that. The tip jar is for all of us, because we are all part of the same team.

The one alcoholic beverage I’ve served the most throughout my career is … either Bud Light, Coors Light or Budweiser. They are, by far, the most popular drinks.

When I won Best of Philly in 2010 … I was astonished! The owner called me and said, “John, I have some good news and some bad news for you. The good news is that you won Best of Philly for Best Bartender. The bad news is that I just found out now, and the awards ceremony was last night.” To this day, it’s a real honor. I tell people that if you put “best bartender in Philadelphia” into Google, my name comes up. Not many people can google their own name and see an award!

The trick to making a proper martini is … that it’s gotta be cold! Chill that glass! The best martini is a very cold martini.

One thing I will never drink again is … Fireball. Or Jaegermeister. Actually, the worst is Rumple Minze.

A bar trend I’m not a big fan of is … rudeness. A lot of people today say, “Hey you!” or “Yo, yo, yo!” Or they wave money at you.

If you want to play a song for me on the jukebox, please play … Anything by Taylor Swift. I’m a Swiftie. Really!

Please don’t play … “Sweet Caroline.” Ugh.

The percentage of customers that don’t tip or undertip is … 15 percent. Most people who have three draft beers will leave three dollars, which is fine. But some will get four and leave a dollar. Then there are the people who come in saying, “Give me the cheapest beer you got.” I say, “It’s $3.50.” They hand me a five. I give them $1.50. They take it and leave. But, hey, maybe the person was just a little short that day, and I understand that.

The cheapest drink at McGillin’s is … Rolling Rock: $3.50 for a pint. But we also do the Philly Special: $5 for a shot of Jim Beam and a glass of Rolling Rock. That’s not a bad deal. We are not an expensive bar. A Tito’s martini will cost you $12, and you’re getting a lot of liquor.

One menu item I can’t live without is … our shepherd’s pie. Greatest in the city. The “mile-high meatloaf” is also fantastic.

If I weren’t a bartender, I would probably be … retired and gardening.

You can find me behind the bar … every Saturday from 11 in the morning until five o’clock. I had more shifts before the pandemic, but then once things opened up, I didn’t come back for a while, just out of concern for my health. And then when I did decide to come back, I didn’t want to take a bunch of people’s shifts away. That’s their livelihood. So one day it is! Saturdays at McGillin’s are fun. We have a lot of tour groups of sometimes 20 people come in. Some groups of Chinese people, some groups of German people, French groups. We actually have menus printed in various different languages.

The question customers ask me the most is … How long have you been here?!

The lousiest pickup line I’ve heard here is … “Do you come here often?” Oh my God. I see these guys just looking at these girls all night. I tell them to send them a round of drinks. If they’re interested, fine. If not, it didn’t cost you much to find out. Just send drinks over. Don’t just stare.

When McGillin’s went non-smoking in 2008 … at first, we were devastated. But it was actually the best thing that ever happened.

The best cure for a hangover is … water. Just drink lots of water. Nothing else works.

One mistake most bartenders make is … ignoring customers.

I will do this until … they get rid of me. Or I break my hip.

My secret to being a good bartender is … being happy. Even if I am having a bad day. This is a service industry. Nobody wants to see Mr. or Miss Miserable behind the bar. As Taylor says, shake it off!

The No-B.S. Guide to the 2024 Pennsylvania Primary

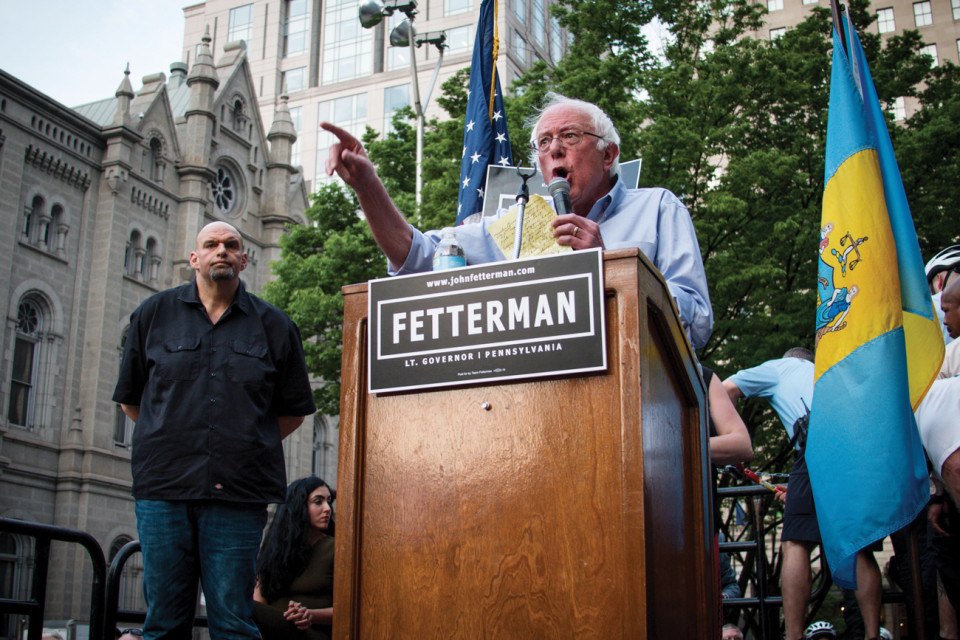

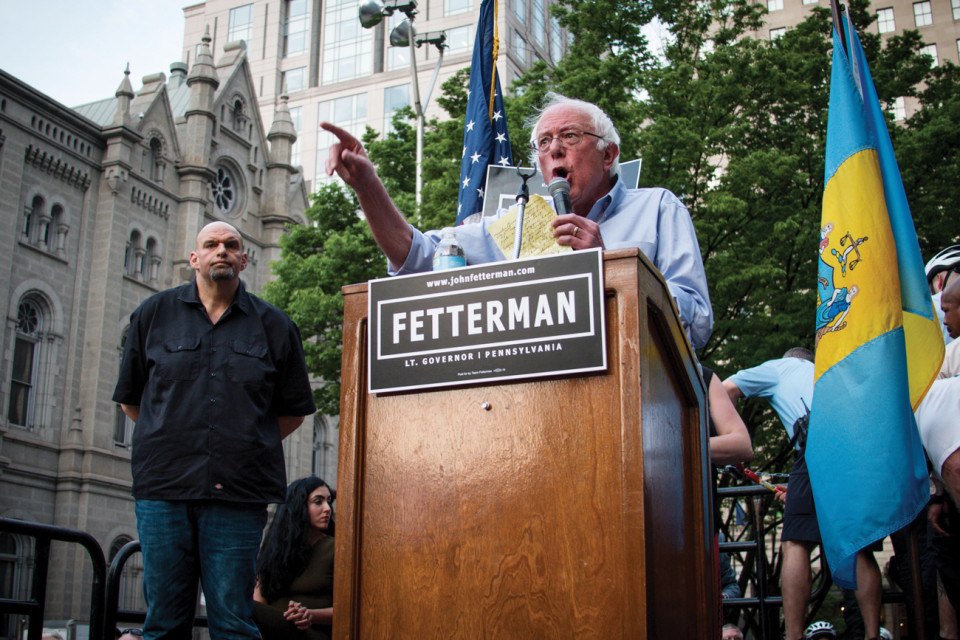

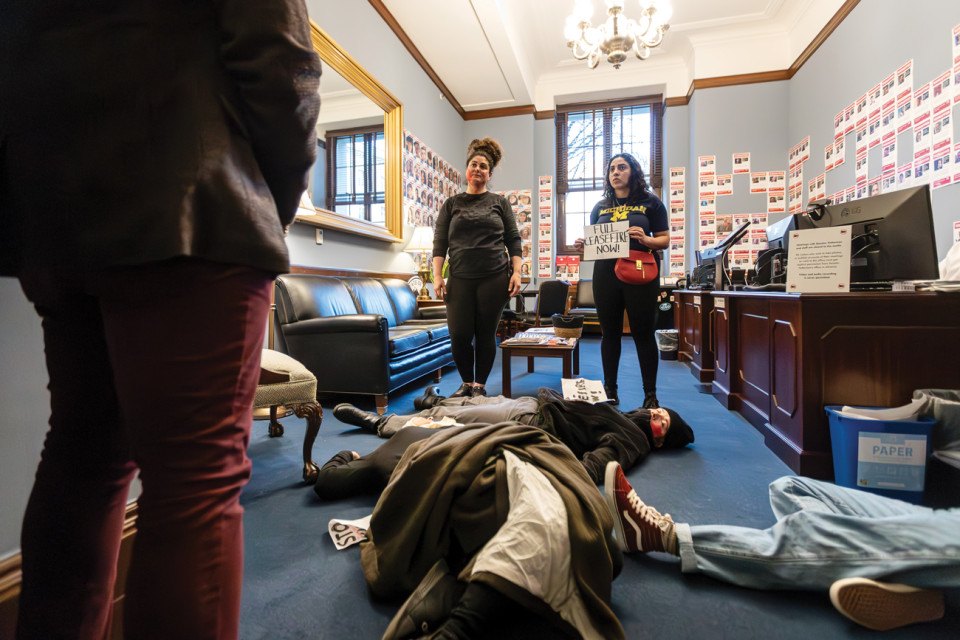

Who will emerge from the 2024 Pennsylvania primary? / Photograph by Mark Makela/Getty Images

The biggest-ticket races in this year’s Pennsylvania primary election have been snoozes for some time. The major-party nominees for the presidential election on November 5th have been set for months. (Democrat Dean Phillips and Republican Nikki Haley both appear on the Pennsylvania primary ballot but each dropped out in early March after Super Tuesday.) The only major question is how many Democratic voters will abstain or write in a vote of “uncommitted” in protest of President Biden’s handling of the Israel-Hamas war. In the all-important race for one of Pennsylvania’s two U.S. Senate seats, both major-party candidates — Democratic incumbent Bob Casey and Republican challenger Dave McCormick — are running unopposed.

But that doesn’t mean there aren’t several important races to vote on this Tuesday. The results of the race to become Pennsylvania’s Attorney General will guarantee a fresh face in the seat — but which one? And the races for auditor general, treasurer and the Pennsylvania House will have implications for the balance of power in the state.

It’s okay if you haven’t kept up with all of the drama surrounding these races — we don’t blame you, there’s a lot going on. That’s what this election guide is for. It’s a simple, brutally honest breakdown of the candidates’ pros and cons as we prepare for the April 23rd Pennsylvania primary. Here are your choices.

The offices up for grabs in the Pennsylvania primary:

- U.S. Senate

- U.S. Congress

- Attorney General

- Auditor General

- Treasurer

- Pennsylvania State House and Senate Races

- Ballot Questions

U.S. Senate

Democratic incumbent Senator Bob Casey is running unopposed in the Democratic primary. Same for opponent David McCormick in the Republican primary. Pennsylvania is one of the battleground states that will determine whether Democrats keep control of the Senate in 2025. If Republicans turn out in large numbers to vote for Donald Trump in the fall, that would hurt Casey’s chances.

Congress

This cycle, there’s only one competitive Congressional election in Philadelphia. The showdown is between veteran incumbent Dwight Evans and former Register of Wills Tracey Gordon.

Dwight Evans

The basics: Congressman from Northwest Philly seeking his fifth term. He previously served as a State Rep for 35 years.

The case for Evans …

- He’s a shrewd politician. He’s got nearly 50 years of political experience, from the state House to the U.S. House of Representatives. And he’s an elder statesman; Evans’s work in D.C. has touched on affordable housing and securing funding to combat the region’s gun-violence crisis.

- He’s an establishment darling. He’s heavily backed by the Democratic Party machine alongside the powerful Northwest Coalition (which also includes the likes of Mayor Cherelle Parker and kingmaker Marian Tasco). In a presidential election year, such endorsements are a competitive advantage, particularly in a contested primary race.

The case against Evans …

- He’s been in power for a very, very long time. Seniority matters in politics, but Evans, who’s closing in on half of a century in elected office, is in many ways the embodiment of the status quo. If you don’t like the status quo …

Tracey Gordon

The basics: Former one-term Philadelphia Register of Wills; she’s previously run for three other seats over the years.

The case for Gordon …

- She could make history. A Black woman has never been elected to Congress in the Philadelphia area.

- She’s not afraid to challenge establishment candidates. Gordon has run for different seats throughout various election cycles, including City Commissioner, City Council and State Representative. She broke through in 2019 with a victory that made her the the first woman elected Philadelphia’s Register of Wills.

The case against Gordon …

- She recently lost her reelection as Register of Wills. Can she convince voters to send her to D.C. after serving just one term in a Philly row office?

- That one term was … controversial.

Attorney General

Five Democrats and two Republicans are running to fill the seat previously held by now-Governor Josh Shapiro. (Michelle Henry, who was appointed to the AG role after Shapiro’s gubernatorial win, isn’t running.) Whoever wins the general election will have large shoes to fill.

Democrats:

Keir Bradford-Grey

The basics: Longtime chief public defender who has served in both Philadelphia and Montgomery counties.

The case for Bradford-Grey …

- She could make history. If elected, she would be the second woman elected and first Black person to serve as AG in Pennsylvania.

- She is arguably the most progressive candidate in the race. Keir has garnered a reputation for advancing criminal justice reform and protecting consumers. She previously helped to replace cash bail penalties with community service for those charged.

The case against Bradford-Grey …

- She’s is arguably the most progressive candidate in the race. At a time when progressive DAs across the nation (such as Philly’s Larry Krasner) are under harsh scrutiny, will Pennsylvanians really steer away from the “tough on crime” appeal that predecessor-now-governor Josh Shapiro made a winning strategy?

Eugene DePasquale

The basics: Former State Rep from York County who recently served two terms as Auditor General.

The case for DePasquale …

- He has already run and won statewide. He’s arguably got the most name recognition. He parlayed a successful run as a State Rep (2007-2012) into two-terms as the state’s Auditor General. One could argue this gives him a big advantage.

- He’s gotten results. In Harrisburg, he’s helped reduce the number of untested rape kits by 90 percent and influenced policy that’s shaped the Commonwealth’s response to unanswered state child-abuse hotline calls.

The case against DePasquale …

- Is he too ambitious? DePasquale is always running for something. (In 2020, he lost his bid for U.S. Rep.) Does he view the AG seat as an opportunity to excel in a specific role — or as a stepping stone?

Joe Khan

The basics: He’s the Bucks County Solicitor, and was notably runner-up to Larry Krasner for Philly DA in 2017.

The case for Khan …

- He’s taken on Trump and won. During the 2020 election, Khan successfully pushed back against Trump’s challenges to absentee ballots in his county.

- Unlike most candidates in this race, he’s actually got tons of prosecutorial experience. He has previously served as an assistant district attorney in Philadelphia and is a former federal prosecutor. At a time when many Pennsylvanians want tougher responses to crime, this gives him an advantage.

The case against Khan …

- He’s politically middle-of-the-road, without much previous statewide reach. It’s one thing for a candidate like Khan to succeed in his county race (lots of direct experience and appeal on a smaller scale) — but can he win statewide in a crowded field when he’s neither starkly progressive nor decidedly moderate?

Jared Solomon

The basics: He’s been a State Rep in Northeast Philly since 2016.

The case for Solomon …

- He’s raised more money than the other AG candidates. With over a million dollars in the bank, Solomon is running TV ads and speaking on his record. It’s impressive and shows that he’d be prepared to take on a Republican opponent in November.

- He has no problem calling out the B.S. in his own party. In Pennsylvania, where both Democrats and Republicans have noticeable flaws, it’s refreshing to see elected officials call out the problems on their own team. Solomon was among the first to speak out about corruption involving now-disgraced former City Councilmember Bobby Henon and has advocated for institutional changes (such as open primary elections).

The case against Solomon …

- Fund-raising advantage aside, he lacks a strong base of political support. Nearly two dozen state House officials have endorsed him, but he didn’t come close to the delegate count needed for endorsement by the state party. The state couldn’t come to a consensus on an endorsement, but in those proceedings, Solomon didn’t fare well.

Jack Stollsteimer

The basics: He’s been the District Attorney in Delaware County since 2019.

The case for Stollsteimer …

- He’s successfully flipped a seat. As the first Democrat to ever serve as the District Attorney of Delaware County, that’s nothing to gloss over. As Democrats strive to flip other seats across the Commonwealth, a case can be made that Stollsteimer’s crossover political appeal is an advantage.

The case against Stollsteimer …

- He might be too moderate to appeal to some Democratic voters. Diverse activist groups within his county have criticized him for his office’s response to the death of eight-year-old Fanta Bility, a young Black girl who was shot by police officers. (They would later have their manslaughter and involuntary manslaughter charges dropped as part of a plea deal.)

Republicans:

Dave Sunday

The basics: He’s been the District Attorney of York County since 2018.

The case for Sunday …

- He’s a career prosecutor. Before serving as York County’s DA, he served as the chief deputy prosecutor. He was previously appointed as special assistant U.S. Attorney for the Middle District of Pennsylvania, where he took on controversial matters pertaining to criminal cases.

- He was endorsed by the Pennsylvania GOP. Early backing by one’s party doesn’t hurt a candidate who’s going against a Democrat who can’t say the same thing. (The Democratic State Committee didn’t endorse a candidate for AG this primary.) As a result, Sunday appears to be the favorite to win in this primary.

The case against Sunday …

- He’s a party favorite at a time when that could be a liability. His opponent argues that voters need an AG who “focuses on prosecution, not political posturing.” Ouch. As Republicans face more scrutiny across the board due to their ties to Trump, could such an endorsement backfire? It’s the risk Sunday — and his party — will have to take for themselves.

Craig Williams

The basics: He’s a State Rep in Chester and Delaware counties.

The case for Williams …

- He’s taken on controversial Philly DA Larry Krasner. For Republicans, Williams serving as the impeachment manager against Krasner in the state House is considered an ultimate flex.

- He has strong prosecutorial and legal experience. He’s previously served as a federal prosecutor, a corporate lawyer, and deputy legal counsel to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, along with other roles.

The case against Williams …

- He doesn’t have as much political support (or momentum) as Sunday. While Sunday has notable endorsements from the likes of the PA Republican Party, Republican Attorneys General Association, and Pennsylvania Sheriffs Association PAC, Williams doesn’t have any major endorsements for his contested race. Not a good look.

Auditor General

Two Democrats are running to flip the seat currently held by Republican Timothy DeFoor, who’s running unopposed. Whoever wins the general election will either strengthen (Democrats) or reinforce (Republicans) what political power that party has statewide.

Democrats:

Malcolm Kenyatta

The basics: He’s been a State Rep in North Philly since 2018.

The case for Kenyatta …

- He could make history. If elected, he would be the third Black candidate (following DeFoor and Lieutenant Governor Austin Davis) and first openly LGBTQ person to win a statewide race in Pennsylvania history.

- He’s backed by the Pennsylvania Democrats. To earn one’s party backing during a contested statewide primary is no easy feat. That alone makes Kenyatta the favorite to win on April 23rd.

The case against Kenyatta …

- He lacks relevant experience for this seat and appears perhaps too politically ambitious. Unlike his primary opponent, Kenyatta has no experience in auditing or government finance. This could spell trouble for him in a November head-to-head with incumbent DeFoor — the first Black candidate to ever win a statewide race in Pennsylvania. It doesn’t help that Kenyatta — who’s also running in a contested race for reelection to his state House seat — lost in a bid for U.S. Senate in 2022. That’s a lot for his party (and more importantly, voters) to keep up with as we head into a competitive November.

Mark Pinsley

The basics: He’s the Lehigh County Controller since 2020 and previously the commissioner in Whitehall Township.

The case for Pinsley …

- He’s the only candidate with relevant experience. Unlike Kenyatta, Pinsley — like DeFoor before winning Auditor General in 2020 – has served as controller in his respective county.

- He’s gotten results. Throughout his campaign, he touts that as controller, he’s saved Lehigh County an astounding $3 million in workforce health-care spending and an impressive $100,000 in banking fees.

The case against Pinsley …

- His campaign lacks political enthusiasm and momentum. While Pinsley has notable experience, he’s a long shot due to Kenyatta’s near total-domination in endorsements.

Treasurer

Two Democrats are running in the Pennsylvania primary to take the seat currently held by Republican Stacy Garrity, a devout Trumper and 2020 presidential election denier, who is running unopposed. Again, whoever wins the general election will either strengthen or reinforce what political power that party has statewide.

Democrats:

Ryan Bizzarro

The basics: He’s been a State Rep in Erie County since 2012.

The case for Bizzarro …

- He’s a longtime elected official. He has more tenure in elected office than all of the other candidates running for this position. With six terms in the state House, he can lean on his experience and connections.

- He’s backed by the Pennsylvania Democrats. With the state party’s endorsement and the backing of several prominent party leaders, Bizarro is a clear front-runner to win the primary.

The case against Bizzarro …

- He has no relevant experience for this seat. Neither he nor his primary opponent has experience in finance-related work. This could spell trouble in November when going head-to-head against the incumbent Garrity.

Erin McClelland

The basics: She’s an addiction counselor and entrepreneur from Western Pennsylvania.

The case for McClelland …

- She’s an outsider. Unlike Bizzarro, McClelland isn’t an establishment darling. She’s running a grassroots campaign focused on advocating for public sector workers.

The case against McClelland …

- She lacks political experience and campaign momentum. With no relevant experience or major endorsements, she’s a long shot due to the overwhelming support Bizzarro has garnered.

State House and Senate Races

There is a contested primary race in the 5th Senatorial District as well as in the 10th, 172nd, 181st, 188th, and 190th House Districts. The Committee of Seventy has a helpful guide on the races.

Ballot Questions

Philadelphians voting in the Pennsylvania primary will see one ballot question when they enter the voting booth Tuesday, regarding whether or not the city should provide legal support for Registered Community Organizations for their efforts on zoning matters. Billy Penn broke down the question into really, really plain English here.

Are These Taylor Swift Lyrics About Jason Kelce?

Jason Kelce and Taylor Swift during Super Bowl LVIII on February 11, 2024. / Photograph by Harry How/Getty Images

This past Friday night I got into an Uber to meet my friends for dinner, and Taylor Swift’s “The Alchemy” was playing. It’s the 15th track on The Tortured Poets Department, so I hadn’t gotten to it yet in my listening of the just-released album. Slowly it began to dawn on me: “Oh my God, this song is about Travis Kelce!” I exclaimed to the driver who did not respond. As the song ended I realized he was just playing pop station 96.5 — renamed “Ninety Swift Five” for the day and playing a new Taylor Swift song every 13 minutes — which is maybe just the station he plays when his passenger is a white millennial woman.

We’ll all remember where we were when we realized The Alchemy was about Travis Kelce.

— Alex Goldschmidt (@alexandergold) April 19, 2024

So, okay, it wasn’t gonna be a five-star Swiftie friendship formed in the RAV4 that night. But I was right about my lyrical interpretation. The song isn’t subtle. “So when I touch down, call the amateurs and cut ’em from the team,” Swift sings, employing some private-jet/football wordplay. “These blokes warm the benches. We been on a winning streak.” Call an ambulance for Joe Alwyn, Matty Healy, and all her British exes.

I could do this all day. Taylor Swift plants Easter eggs for her fans, and decoding them is half the fun. What might seem far-fetched or coincidental with normal pop songwriters is often rewarded in the Swiftie fandom. She is a “Mastermind,” after all. But when all that tea-leaf reading also involves one of my — nay, Philadelphia’s — favorite people, I’m all in.

Anyone can analyze The Tortured Poets Department’s lyrics to figure out which songs reference Swift’s boyfriend Travis Kelce. (“The Alchemy” and “So High School,” if you’re keeping track.) But I’m skipping right to Jason Kelce.

“Shirts off”

Jason Kelce celebrates with his shirt off after the Kansas City Chiefs score a touchdown during the playoffs. And Taylor Swift was right there in the box with him. / Photograph by Kathryn Riley/Getty Images

The bridge in “The Alchemy” talks of winning and a trophy and Travis running over to Taylor. Of course, our mind instantly goes to their iconic post-Super Bowl embrace. But wait …

Shirts off, and your friends lift you up over their heads

Beer sticking to the floor

Cheers chanted, ‘cause they said

There was no chance, trying to be

The greatest in the league

I’m sorry, but who took their shirt off to celebrate a championship touchdown? That’s right, the love of our lives, Mr. Jason Kelce. Right next to Taylor in the box, and undoubtedly spilling some beer on the floor. Iconic.

“I circled you on a map.”

Jason Kelce and Taylor Swift react during the playoff game between the Kansas City Chiefs and the Buffalo Bills. / Photograph by Kathryn Riley/Getty Images

Also in “The Alchemy,” Taylor sings that she “circled [Travis Kelce] on a map.” Understanding this line requires knowledge of the backstory, not just of Taylor Swift, but also of the Kelces’ New Heights podcast.

Having already won two Super Bowls (including the Kelce Bowl against us, but let’s move past it) and being arguably the best tight end in the NFL, Travis Kelce was already one of the most famous football players before he started dating Taylor Swift.

But being merely football-famous means that some in Taylor’s fanbase who don’t follow the NFL (or watch TV commercials, apparently?) didn’t know that Travis Kelce was a superstar in his own right. This led to some saying — and more joking — that Taylor put him “on the map.”

It became a running joke, and of course made its way into New Heights.

When they were reviewing fan costumes, singer Jax’s TikTok-famous Halloween costume was included.

The next month, the brothers were reviewing fan art on New Heights. Eagle-eye fans (and Travis) would notice that a fan’s cartoon drawing included Travis wearing a shirt that said “On the Map” with his face atop the U.S. map. “Shout out to Taylor,” Travis Kelce commented.

Travis Kelce reacts to fan art of himself and Jason Kelce with an Easter egg Taylor Swift reference

Is it too much of a stretch to think Taylor Swift listens to New Heights? Her Coachella wardrobe would suggest it is not.

Taylor Swift (wearing a New Heights cap!) and Travis Kelce at Coachella / Photograph by Gilbert Flores/WWD via Getty Images

P.S. After she wore that hat, it sold out. Because of course it did.

“That impression you did of your dad.”

In The Tortured Poets Department bonus track, “So High School,” Swift sings “I feel like laughing in the middle of practice, to that impression you did of your dad again.”

Again, we’ve got New Heights to thank for our insight into this reference. During the podcast both Travis and Jason Kelce frequently mimic their dad, Ed Kelce.

Those Papa Kelce impressions are just too good pic.twitter.com/up7hZu8KFu

— New Heights (@newheightshow) April 19, 2024

So, the required reading list has expanded: The Taylor Swift cinematic universe now includes the Kelces’ output into the world. And really, it’s fitting that the New Heights podcast would play such a prominent role here, as it’s also where the world first learned of Travis’s love for Taylor, as he recounted his attempt to court her via friendship bracelet at her concert.

Which brings us to our final lyrical reference, also from “So High School.” “You knew what you wanted, and boy, you got her.”

How to Get a Doctor’s Appointment Sooner

Insider tips to get a doctor’s appointment sooner

It’s easy to feel helpless when you need to see a doctor but can’t get in for weeks or months (or longer!). But there are steps you can take to potentially speed up the process. Here, tips and strategies for getting a doctor’s appointment sooner.

Be flexible.

Sometimes (not always), health systems or practices automatically offer multiple locations for your appointment, noting if one has earlier openings. If that info isn’t offered up, ask: Might another spot (or telemedicine) have an appointment sooner? Same deal with your providers, says Adam Edelson, vice president of ambulatory operations at Main Line Health. Could you get in faster if you saw a different MD? A nurse practitioner or physician’s assistant? This, too, is worth searching out on the scheduling portal or calling to ask about, as options for other providers aren’t always apparent online.

Snag a cancellation.

Make your appointment, then sign up to be notified when there are cancellations. You can ask for this on the phone or check online — some scheduling portals let you opt to be waitlisted for earlier slots. Hot tip from one South Philly patient: “I’ve found that if you go in and hit ‘reschedule,’ you can find earlier times that didn’t show up on the waitlist.” Otherwise? Call and ask every day — especially if you’re dealing with a smaller private practice. “I always advise our patients to just give us a call,” says Jacqueline Williams, office manager at Advocare Fairmount Pediatrics. “Sometimes, cancellations get called in or show up on the portal, and we can put you right in there.” Also, she adds, a practice can sometimes shuffle patients around and get you in.

Try the app for that.

ZocDoc — a free app and website — matches you with local practitioners (including specialists) who take your insurance and have fairly immediate openings in their schedules. Each available appointment time — telemedicine and IRL — is clearly displayed and easy to book right there on the site. You can also peruse ratings from patients to help you choose your doc.

Illustration by James W. Yates

Go straight to the source.

If you know your doctor, try messaging him or her on the portal. When patients message him, “I can schedule visits myself,” says Charles Bae, a neurologist and associate CMIO for connected health strategy at Penn Med. In fact, he adds, sometimes that’s the most efficient route for both patient and doctor. If doctors don’t want to schedule patients or can’t, Bae says, they can simply tell you to go through the usual channels. Philynn Hepschmidt, Penn Med’s VP of patient access, says such messaging might even save you an appointment: Some dermatological conditions, for example, can be treated with photos and info exchanged over the portal. “I go to the patient portal first for everything,” she says.

Can’t get in to see that specialist? Ask your primary-care doc for help.

Hepschmidt says that referring doctors can often note electronically to specialists which patients need to be seen within a certain amount of time — some conditions merit prioritization, and specialists can see this. But such electronic flags aren’t necessarily universal, and in a pinch, a note or call from another doctor might speed things along.

Don’t lie.

It’s tempting, maybe, to exaggerate your condition in hopes of getting in sooner. “I do understand why you might want to,” says Hepschmidt, “but there are patients who truly do need to get in, and this will take away from them.” Health systems really do prioritize patients with urgent needs. Don’t be a jerk.

Published as “The Fast(er) Track” in the May 2024 issue of Philadelphia magazine.

Where to Get Medical Care in Philly Besides the Doctor’s Office

You’ve got options beyond a traditional doctor’s appointment when you need medical care.

Can’t wait for the next opening in your doc’s schedule? Don’t have a primary-care doctor? (Eighteen percent of us don’t, according to a 2018 city survey.) Here, a rundown of places you can turn to for medical care when you need it.

Phone and Websites

The scoop: Maybe, just maybe, you don’t need that appointment, and a portal message or phone call to the office will suffice. You can also call the state’s free 24/7 nurse line with any medical questions: 1-833-510-4727.

Examples: Nemours Children’s Health has a free symptom-checker on its website offering detailed guidance for common ailments, including whether a visit is needed; many practitioners offer similar help via portal messages.

Good for: When you’re not sure you need a doc or what level of care you might need — urgent care? Specialist? ER? Also good when you suspect you could manage something at home … if you only knew how.

Not good for: Sometimes the doctor just needs to see you to help you.

Payment: Free. Some health systems/practices in the country now charge for portal messaging, but as yet, that isn’t widely practiced in Philly.

Urgent Care

The scoop: A walk-in-friendly model for non-life-threatening illnesses and injuries, without the hassle or expense of a trip to the ER. Most offer appointment times in addition to walk-ins. Often open outside typical doctor office hours.

Examples: Vybe, myDoc, AFC. The big health systems (Temple, CHOP, Christiana, Penn, Jeff, Main Line Health, Nemours, Cooper, etc.) also offer urgent-care centers; ditto Rothman Orthopaedics.

Good for: Acute illnesses (e.g., mild allergic reactions, infections, congestion, food poisoning, pink eye), minor injuries (e.g., bites, sprains, minor breaks or dislocations, minor burn and wound care), lab testing, screenings and X-rays, physicals, vaccinations.

Not good for: Life-threatening injuries or illnesses (e.g., serious head injury, heart attack, stroke); procedures that require anesthesia or surgery.

Payment: Most insurance covers urgent care — check with yours to see who’s in-network. Some centers display prices for “self-pay” visits for the uninsured on their sites.

Scheduling woes / Illustration by James W. Yates

Convenience Clinics

The scoop: A walk-in model similar to urgent care but with more limited services and slightly lower out-of-pocket costs. Often shorter wait times than urgent care and staffed by nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Sometimes there are virtual options, too.

Examples: In some states, you can find convenience clinics in Target, Walmart, some grocers and chain drugstores. In Greater Philly, we’re mostly just talking CVS Minute Clinics.

Good for: Treatment of minor illnesses like ear and sinus infections, flu, colds, UTIs and strep; minor wounds and injuries such as blisters, sprains, back pain (but not severe cuts); vaccinations and STI screenings.

Not good for: More severe injuries or illnesses; anything requiring stitches, CT scans or X-rays.

Payment: Covered by some insurance — check with yours. The uninsured pay out-of-pocket; the CVS website lists prices.

Clinics and Health Centers

The scoop: Several dozen free and low-cost health centers around the city offer a range of services (e.g., primary care, basic dental, optometry, podiatry, behavioral health). Find a comprehensive guide to all of them at phila.gov/primary-care.

Examples: The nine city-run health centers, Esperanza Health Center, Puentes de Salud, Dr. Ala Stanford Center for Health Equity, Wyss Wellness Center. To name just a few.

Good for: Free or low-cost primary care — including preventative care, screenings, managing chronic conditions, medical consults, diagnosing and treating illness and minor injuries — plus, often, pediatrics, ob-gyn services, and behavioral health.

Not good for: Not all clinics are easy to get into — some, not all, have problematic wait times. Services vary by clinic. Check the site and/or call before you go.

Payment: Most clinics accept most insurance (check websites or call) and offer reduced-rate and sliding-scale payments for uninsured patients.

The Pharmacy

The scoop: Great for advice on remedies for minor issues — say, managing pain, what sorts of things might help your coughing toddler, how to find relief from symptoms when you feel like garbage. Your local pharmacist can’t prescribe anything but can tell you what to buy OTC.

Examples: Too many to name. (Try your locally owned neighborhood options.)

Good for: OTC recommendations and guidance; prescription education; vaccinations (sometimes); insights into managing drug side effects or tips on managing chronic conditions like diabetes or pain.

Not good for: Diagnosing or evaluating patients, prescribing medications, or administering exams.

Payment: Free! No co-pay required here.

Video and Telemedicine

The scoop: If you’ve got internet service and a video/audio-enabled device, then you can see a doc. Most providers (including specialists) offer some form of tele-med these days, some even in what are traditionally “off” hours.

Examples: If we’re talking providers that offer services to non-established patients — and offer urgent-care/on-demand services — some include Jefferson’s JeffConnect, Penn Med OnDemand (PMOD), Teladoc, Vybe, Nemours, Main Line Health.

Good for: Consults, diagnoses and treatment for … well, more than you’d think, including lice, rashes, vomiting, sinus infections, flu, strep, UTIs, ear infections, pink eye, bronchitis and more. And again — many specialists also offer telemedicine visits.

Not good for: Emergencies (e.g., excessive bleeding or severe cuts); change in mental status; chest pressure; screenings, labs or scans.

Payment: Coverage and prices vary — check provider websites. Teladoc, for one, starts at $75/visit without insurance. PMOD self-pay visits range from $70 to $395; JeffConnect is $59 for an on-demand call.

The ER

The scoop: The last-resort resort. Because of the expense and long wait times — in Philly, the Inquirer recently reported, ER visits typically take almost an hour longer than the national average — you don’t want to go to the ER unless your condition demands it.

Examples: The Philly region has 36 hospitals providing emergency care.

Good for: Technically, they can treat nearly anything, but the ER is best used for — yup — emergencies (e.g., severe burns, chest pressure, serious injuries/accidents/breaks, extremely high fevers that don’t get better with medicine, allergic reactions).

Not good for: Inexpensive treatment, caring for chronic conditions.

Payment: The average ER cost for the uninsured in Pennsylvania is $1,645. Costs for the insured vary by coverage.

Published as “The Doctor Won’t See You Now” in the May 2024 issue of Philadelphia magazine.

Why Is It So Hard to Get a Doctor’s Appointment in Philadelphia?

Why has getting a doctor’s appointment become a waiting game? / Photo-illustration by C.J. Burton

I’m sitting in an armchair in a brightly lit room, my hands gripping my knees, head bowed as if I’m deep in prayer, when I feel the first needle pierce the back of my scalp. One sharp prick. My eyes water.

Then comes number two. A familiar relief washes over me as I feel the sting of the third shot, then the fourth. The doctor presses a small square of gauze to the area, pats away tiny dots of blood, then fluffs through my hair to repeat the process in another spot.

These quick little jabs to the back of my head deliver doses of cortisone to treat an autoimmune condition called alopecia areata. It causes me to sporadically develop bald spots the size and shape of coins — from dimes to half-dollars — on my scalp. The condition enjoyed a moment in the spotlight a few years ago when it was revealed to be the catalyst behind Jada Pinkett’s shaved head, which was the catalyst behind the Chris Rock joke at the Oscars that was the catalyst behind the infamous Will Smith slap.

Despite the prestige, I mostly associate my ailment with stress — not cancer stress or even torn-rotator-cuff stress, but stress in the sense that I’m vain and the bald spots can grow, and I don’t have Jada’s Hollywood bone structure. So when I notice a new dime or quarter on my head, I simmer in self-conscious helplessness until I can get in to see a dermatologist for the shots. When I’m lucky, it’s a short wait — a few weeks, maybe even days. When I’m unlucky, it can be a month or more — eons in simmering time. Once, some years back, the scheduler told me they were booked out for six months, at which point, she offered, I could try again. Or look elsewhere.

I was incredulous, then perplexed. I’d already left my last dermatologist because of exceedingly long waits for appointments. And anyway, I wondered at the time, what the hell is even happening here? This was Jefferson Med — a behemoth! My appointments rarely exceed 10 minutes. I’m punctual. I’d birthed two babies in their hospital, even courteously scheduling one of them. Couldn’t we work something out?

Eventually we did, in that I called every day until I finally snagged someone’s cancellation. And once there? The doc told me I could message him in the portal when I needed to be seen and he’d squeeze me in himself. The offer felt like a winning lottery ticket, and I cashed in a couple times, gratefully. But this past fall, I got a Dear Patient letter — he was moving out of state. I’d have to start fresh with a new doctor, hopefully working my way into a new portal, a new safety net.

And so there I find myself one frigid day last January, relating all of this semi-sheepishly to the new doc between jabs: “I mean, I know it’s not life or death or a torn rotator cuff. … ” But she’s a sympathetic audience: Roughly half of her patients have mentioned waiting to her, she tells me. And she has a story of her own, about a time her father — not a Jeff patient — noticed a lesion on his head and called for a dermatology appointment. Six months, they told him. He took it.

Later on, he happened to mention this to his daughter, who was at that point still a medical student but knew enough to tell her dad to call back, giving him specific language to use — magic words I no longer remember. (Bleeding? Growing?) Tell them there was suspected malignancy, she directed. That word I do remember: malignant. Which, it turned out, it was.

The callback got him the appointment, and he was promptly diagnosed with a particularly aggressive form of cancer. Today, after chemo and radiation, he’s doing fine, my dermatologist tells me — but, she adds, dabbing the last droplets of blood from my scalp, his own doctor told him that had he waited that six months, it would have been too late.

By now, most of us understand that access to care is one of the many issues that plague America’s beleaguered health-care system. But there’s been a sense, I think — at least among those of us in the habit of absorbing the daily headlines — that the problems have mostly revolved around certain specific, desperate contexts. The medical deserts plaguing rural America, for instance. Niche specialists facing exceptional bursts of demand, like child psychiatrists since COVID. And the increasing number of patients in our country — the poor, the undocumented, those seeking reproductive or gender care — at the mercy of merciless legislative crusades.

What’s becoming more and more apparent, though, is how much more widespread, even mundane, the issue of getting to your doctor — or a doctor — really is, particularly when it comes to primary and preventative care. You know, the kind of care that keeps chronic conditions in check and keeps you out of the more expensive, overcrowded ER and also just generally helps keep you up to snuff and/or alive.

When I say widespread: Anecdotally, everyone I know — and probably you, too — has a story about waiting. A friend of mine who called for a physical with her Jefferson-based primary-care doctor in October couldn’t be seen until February. Another got a quote for a year-and-a-half waitlist to see a Penn Med gynecologist for an annual exam. When she looked instead to private practice, she took the best they could offer: a telehealth visit in two months. Still another friend who had an iffy mammogram at Penn was told she’d need to wait a stomach-churning month before she could even call to make an appointment for a biopsy.

Meantime, a Main Line Health patient I know needed a sick appointment, but her doctor had left the practice and they were booked out three months for “new patients.” When her asthma flares up, she says, her MLH pulmonologist appointments are regularly three to six months out. One of my neighbors waited upwards of four months last year for a run-of-the-mill pediatric allergy appointment at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), while another sought an appointment with a CHOP autism specialist and was told there were none, and no waitlist, no cancellations. “Please don’t call back,” the scheduler said.

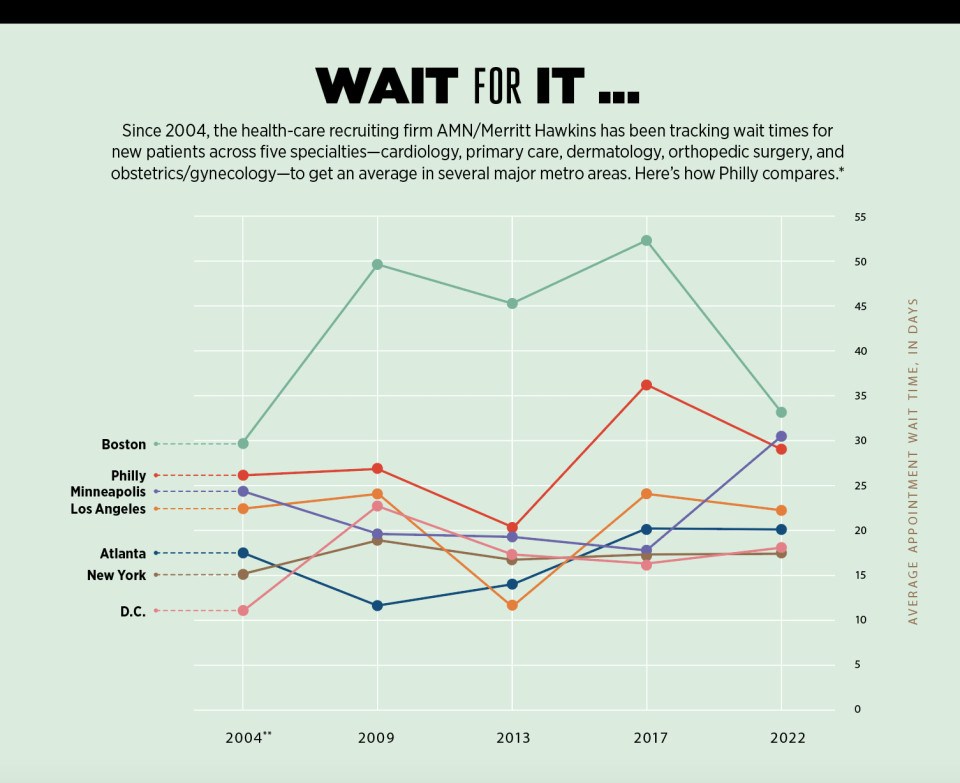

It bears mentioning that all these people are insured, English-speaking, internet-literate city dwellers who have some flexibility within their schedules. It’s hard to imagine getting to see a doctor is easier or more expedient for anyone else. Last May, the Inquirer ran a piece about the sole low-cost, city-run primary-care clinic in the Northeast — a place at which 40 percent of patients lack insurance or the money to pay a typical medical bill. Many are immigrants. Patients there might wait up to a year to see a doctor, squeezing into cubicles for exams. Still, like so many frogs in so many pots, it’s been easy for us collectively to miss the extent of the trend here — at least, until a 2022 survey from health-care recruiting company AMN/Merritt Hawkins put numbers to it. Across five different specialties, the average wait times for new patients in 15 of the country’s largest metropolitan areas, Philly among them, were as long as they’ve been since the company started tracking them 20 years ago — up 24 percent, to an average of 26 days.

Here in Philadelphia — a city that trains one of every six doctors in America, in a metro area with one of the highest per capita rates of health-care workers in the country — the average wait to see a cardiologist was 39 days (up from 28 in 2017, which was up from six in 2013), 34 days for a family-care practitioner (up from 17 days in 2017), and 59 days for an ob-gyn (up from 51 days).

Why, though? The question that nagged at me years back with the dermatologist has only intensified as everything else in the world seems to be getting faster, more geared to our on-demand economy. Why — especially in this eds-and-meds city — can it take such a maddeningly long time to see a doctor? And in a health-care system teetering on the backs of already-overburdened providers, is there anything anyone can do about it?

“When I was a kid,” says Elaine Gallagher, a brisk 50-something senior vice president at CHOP, “I didn’t know anyone who had a food allergy. Right?”

I think back to my own childhood, in the 1980s. I knew a couple kids who were allergic to peanuts or chocolate — but only a couple. I know a whole lot more now, which is the point Gallagher is making. She leads CHOP’s six specialty practices, the hubs for its pediatric specialists — including the food allergy program, now one of the most in-demand appointments in the system, with new-patient waits that frequently exceed a year.

“I’ve worked here for over 30 years,” she says. “And for over 30 years, we’ve been talking about access. It’s just a very difficult problem.” Part of the inherent difficulty, she explains, is the way demand has evolved nationally over the years, and how certain conditions have exploded — conditions that require follow-ups, specialists, time. Like food allergies diagnosed in children, which the CDC says have grown by 50 percent since the 1990s.

Also up? Developmental disabilities. Type 2 diabetes. Anxiety. Depression. All of this is according to a 2023 study from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM), which also showed that between 2017 and 2020, obesity affected almost 20 percent of our children, up from about 14 percent two decades earlier. (One pediatrician I talked to noted that half the kids she saw that day had childhood obesity, which can bring with it conditions — sleep apnea, disrupted menstrual cycles, elevated cholesterol, etc. — that require closer tracking … and thus more follow-up appointments.)

Meantime, not only has the number of pediatric doctors not kept pace with the ballooning need, but a catch-up feels utterly out of reach, given current trends. Fewer medical-school graduates are choosing to go into pediatrics, Gallagher says — some 600 fewer from 2019 to 2023, to be exact. This year, 13 of the 15 accredited pediatric sub-specialty training programs saw fewer applicants nationally than in previous years, Gallagher adds, and couldn’t even fill all their slots.

But wait! It gets worse. Much of medicine is facing a similar plight: On one side, there’s seemingly endless demand — we’re a growing population and an aging population, and people over 65 go to the doctor at least twice as much as younger people. Six in 10 of us have a chronic condition. And the Affordable Care Act gave more of us the financial means to actually see a doctor. On the other side, supply isn’t growing fast enough to keep up with demand, and not enough doctors are going into the areas where we need them the most.

This is particularly and painfully true when it comes to primary care. In Philly, there’s just one PCP for every 1,243 of us — and that’s actually slightly better than the national average. As a nation, we’re also staring down shortages of neurologists, ob-gyns, pulmonologists, psychiatrists, cardiologists, optometrists, urologists, and critical-care specialists.

At this point, you must be wondering why in God’s name we’re short on all of these doctors when being a doctor in America is still a relatively well-paying, noble, mom-pleasing profession. The answer, like everything else in modern health care, is complicated.

A CliffsNotes explanation might well begin with COVID, which spurred some 145,000 burned-out practitioners to leave the field. (Half were doctors; a quarter were nurse practitioners.) This has been, to put it mildly, a major gut punch to the system — but it was hardly the first blow. A full decade before the pandemic, nurses and doctors were reporting high levels of burnout relative to the general population — too many patients in a day, too much bureaucracy, too much wrangling with insurance, too much work in off-hours.

The burnout and resulting labor shortages have exacerbated the situation for those who remain, notes Christian Terwiesch, a Wharton and Perelman School of Medicine professor who studies operations, innovations and policy in health care — creating “a huge problem that over the last 10 or 15 years has bubbled up to be one of the top three challenges every health-care system struggles with.”

Consider the age of our current medical workforce: Some 30 percent of working docs are 60 or older right now, on the cusp of retirement.”

Another factor is that even as demand has expanded, there’s been no significant expansion in funding for training new doctors. Not for lack of interest from would-be practitioners (hey, did you know medical-school applications shot up during COVID?), but because internships and residencies are largely funded by the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Since 1997, that funding has only expanded to support some 1,200 more residencies. That’s not enough. Especially given the age of our current medical workforce: Some 30 percent of working docs are 60 or older right now, on the cusp of retirement.

Then there’s the paltry rate at which Medicare reimburses doctors for their services — a rate that’s decreased 26 percent since 2001, despite inflation. That means physicians are providing the same services as always but for less money, and spending more to do it. This, the AMA notes, has led more doctors to drop patients who rely on Medicare or Medicaid. This often means — here we are again — longer waits and more hoops to jump for those patients, who scramble to find care elsewhere.

Another whammy: Doctors practicing certain types of medicine — pediatrics, endocrinology, family and internal medicines, for example — make less money than many specialists. This has a little to do with how much training and insurance is required to practice in their areas, but far more to do with the rates at which insurance (both private and Medicare) reimburses their services. Broadly speaking, procedures big and small are valued at higher rates than more preventative, prescriptive, diagnostic general care, and the take-home pay reflects this.

Now, it’s true that your average family practitioner or pediatrician does better than most of us, financially speaking — their median salaries are $255K and $251K, respectively. But it’s also true that plastic surgeons do way better ($619K a year on average). So do cardiologists ($507K) and orthopedic surgeons ($573K). Tack on to that student debt — on average, doctors graduate owing roughly $250K. Even the most altruistic helper-types aren’t totally immune to that math.

So: Swirl the laws of economics together with all these factors over a couple decades, and here we are. The Association of American Medical Colleges predicts a national deficit of up to 124,000 physicians by 2034, but there’s no need to look even that far ahead. “The physician-shortage crisis is here,” American Medical Association president Jesse Ehrenfeld announced last November. “And it’s about to get worse.”

There are variations as to what this crisis (and worse) can look like. As Ehrenfeld noted, there are already swaths of pregnant women in some states who can’t find an ob-gyn; countless Americans have no easy access to specialists. By comparison, Philly boasts an embarrassment of riches — unevenly distributed, yes, but riches nonetheless. Still, nobody is immune to the effects of the shortage.

“We’re constantly recruiting,” says Adam Edelson, who runs ambulatory operations as a VP for Main Line Health, a 13,000-employee mega-system. (He’s not alone: I hear this from executives at Penn Med, Jefferson and CHOP as well.) Top-notch doctors, advanced-care providers — every system wants more of them, Edelson says, which is an ongoing challenge. (Not to pile on here, but there’s a shortage of support staff, nurses and midwives, too.) And his is a high-quality urban/suburban health system ranked in 2023 as one of the best employers in the state, with competitive pay and benefits. “I can only imagine what other organizations may face,” he says.

CHOP’s neurology department offers another window into the morass. At 70 neurologists deep, it’s bigger than many entire pediatric practices, Elaine Gallagher points out: “And we still can’t meet the demand.” Any attrition at nearby neurology departments means more patients land at CHOP — which is what’s happened, to the tune of 1,500 more kids over the past two years. And yes, hiring more neurologists would help, she adds — “but there just aren’t a great number of them out there waiting to be recruited.”

Even CHOP can’t get blood from a stone.

But if there’s any good news here, it’s this: We know how to fix this issue. (And by “we,” I mean the AMA, NASEM, medical economists, regular economists.) We know, for instance, that better Medicare reimbursements are crucial. As is tamping down some of the time-sucking, demoralizing red tape insurers put health-care workers through. Also: better loan repayment plans, debt forgiveness, and (yes!) tuition-free education, to sweeten the deal for doctors; easier pathways for foreign-trained physicians to practice here; money to expand residency training programs. Many of these solutions are already in actual pieces of legislation floating around right now.

But therein lies the rub: The task of caulking the sizable gaps in the medi-verse essentially falls to the only system more beleaguered, teetering and glacially slow than health care — the American government.

In the meantime, how would you feel about a group physical? Or AI listening in on your next doctor’s appointment? Or an asynchronous appointment where you’re treated but never actually see a doc?

These are just a few of the ways health care is evolving to deliver care to the people who need it. Tackling delivery is the best way forward, Wharton’s Terwiesch says, in large part because the high demand will never go away, no matter what happens on the supply side. It’s just the nature of health care: If it’s done well, people live longer and consume still more — “like we’re running a race on a treadmill that gets faster than we can ever run.”

Improving care delivery, he says, might just begin with reframing the mission. “We believe that if we keep researching and working, we’re going to find the one thing, the silver bullet that cures the health-care delivery problem we have in this country.” Having recently immersed myself in the canon of health-care troubleshooting, I understand what he means: Could the answer be team-based care? Value-based care? A single-payer system! And so forth.

Instead, Terwiesch says, “I think we’re better off saying, ‘Look, health care is a very complex thing.’” Or — he corrects himself — a mass of interconnected things. And in this mass, “It’s thousands and thousands of little problems plaguing the system. So let’s just acknowledge them, and get to work, and every day, with these thousands of problems, just try to fix one at a time.”

Enter Roy Rosin, the affable, animated chief innovation officer for Penn Med, who has spent a great deal of time over the past decade aiming to fix one problem at a time, particularly the ones that relate to getting more people more care faster. When I called him one day last winter, he rattled off so many different Penn pilots and new protocols — a.k.a. “The Portfolio” — with such enthusiasm and encyclopedic breadth that I could barely keep pace typing.

There are too many to name here, but among some of the more fascinating Portfolio highlights, at least from this layman’s perspective, are these:

- A custom-designed software system that finds unused rooms and spaces in the labyrinthine Penn system where patients can be seen and doctors can work — literally making the best use of its real estate resources.

- A project being run by a sleep neurologist that helps determine for doctors at what point it becomes more efficient to bring a patient in for a visit than to communicate over the portal.

- An asynchronous model — this one in dermatology — that allows a patient to send in photos and information via a portal. The doctor later reviews the treatment plans sans visit, thus hopefully allowing doctors to see more patients, catch skin cancer faster, and get more people with minor problems into treatment “at higher and faster rates.”

Rosin gets really jazzed by the work of “reimagining care models.” One of his favorite examples, among many, is what Penn Med did with breast reconstruction surgery for cancer patients some years back. Because Penn’s a global leader in this arena, there’s always high demand, which has translated to long waits. Part of the issue, Rosin says, was the intensity of the 90-day post-op care schedule — five separate clinical visits for stuff like drain and pain management and checks for motion, infection and scars.

“There was no waste in those visits,” Rosin says — every piece of care was necessary. But, the innovation team wondered, could a Penn home-care team manage drain care and removal? Might some of the motion and pain assessment be done via a portal? Could the surgical site be assessed at home, with photos? When they tried these things, they realized that a 30-minute in-person visit could essentially be reduced to a five-minute phone call, Rosin says, eliminating 50 to 60 percent of in-person follow-up needs. This allowed new breast-cancer patients to get in more quickly without changing outcomes for current patients. And — a bonus — it saved people recovering from surgery a whole lot of schlepping.

You can see why Rosin gets excited about ideas like this. You can also see why so many organizations in Philly’s health-care ecosystem are putting money and talent into exploring and making similar changes. Everywhere around Philly, providers are experimenting with such innovations, from the granular (like those automated text reminders with “cancel” options that cut down on wasteful no-shows) to the massive (see: the telemedicine revolution).

Speaking of telemedicine, some fixes are so widespread that they are now — or soon will be — de rigueur, like online self-scheduling, and the automated “fast passes” that offer patients already in the books earlier appointments when cancellations occur. (This works! Jefferson Health, for one, reports moving up some 4,000 appointments a month by an average of 30 days.) Some fixes involve rethinking who should do what, like the now common practice of having nurse practitioners and physician assistants offer care, or like a CHOP pilot exploring how primary-care doctors can successfully manage certain conditions — headaches, maybe, or constipation — without needing to refer patients to a specialist. Nemours is looking at ways to embed specialties into primary-care outposts to make it easier to access things like preventative cardiology and autism evaluations; it’s also setting up school-based health centers.

Some other solutions seem absolutely wild at first blush, like sharing appointments with other patients who have the same or similar needs. (Maybe not so wild: A National Institutes of Health paper a decade ago found that patients in a shared-appointment model were more satisfied than those receiving ordinary care.) And some proposed fixes are still a bit … unsettling, like AI “listening” in on appointments, ostensibly to help docs with note transcription, summary generation, prescription ordering, and other time-saving efficiencies. “We have a number of AI initiatives on how we might reduce the time physicians spend with the medical record,” Elaine Gallagher says. “Those are in really early stages.”

Medical providers seem to hover between measured curiosity and circumspection when it comes to AI. But the technology will surely continue to speed ahead.”

The providers — at least, the ones I’ve spoken to — seem to hover, as Gallagher does, between measured curiosity and circumspection when it comes to AI. But the technology will surely speed ahead. Last year, one Axios story pointed to the multiple AI tools already “interacting” with patients by listening for signals or voice indicators of self-harm and clinical depression, based on clips of people talking to their doctors.

Of course, the reporter noted, there are some obvious issues here — namely, “a number of privacy concerns as well as worries about accuracy of the data and potential biases.” Which reminds me of something Terwiesch says about trying to move the needle, problem by problem: “It’s a lot of work, and it will keep us busy for a very long time.”

But then there’s this: I can always get in to see Alexis Lieberman. In the 10-plus years I’ve been taking my kids to see their pediatrician, I can’t remember a time I struggled for an appointment. This isn’t because Lieberman isn’t busy; she runs a private practice affiliated with a large regional physician group, and between two offices, she has five providers, nine support staff and 3,000 patients.

Over the years, I’ve awakened her in the middle of the night in a croup-induced panic (twice). I’ve texted photos of rashes and random medical mysteries in off-hours, earnestly messaged her about how to cook my baby’s first bite of egg (“Well, how do you like your eggs?” she answered an hour later), and just generally relied on her for everything from easing coughs to delivering discipline. In my neighborhood-parent circles, this sort of doctoring has made her very popular.

So why, I ask her, can I always snag an appointment at her office with none of the Sturm und Drang that exists elsewhere?

“Because,” she says matter-of-factly, “I made a decision that I want you to be able to.” (Have I mentioned that I love her?)

Lieberman goes on to explain that this decision has really entailed a series of choices. Like, for instance, the choice to open the office’s schedule just two weeks in advance, which, she allows, was scary at first: You lose the financial security of knowing that for months at a time, patients will be steadily pouring in, one after the other. But it also means the books are never too full for people to get a timely appointment. She reserves a certain number of sick slots every day; beyond that, as issues come up or appointments are needed, patients can see if there are slots open and, if not, wait at most two weeks to jump back in and grab an opening.

She’s also chosen, she says, “to do today’s work today.” That means filling out everyone’s school forms that day, no waiting. And if she hasn’t held back enough “sick time,” she stays late to see patients in need. In short: “I work harder on a day when there’s too much work and less hard on a day when there’s less work.”

That she has choice in these sorts of decisions and others — including the one to grow her practice over the years as demand has climbed — is in part a function of the relative autonomy that comes with private practice and in part a function of scale. The fewer dominos you have, the fewer can fall, and the less time it takes to right them, you know?

This is something that Alexander Vaccaro, president of the private Rothman Orthopaedic Institute, talks about. “I have 238 orthopedic surgeons and a staff of 2,200,” he says — compared to tens of thousands at larger systems — “so I have the ability to quickly pivot.” At Rothman, “pivoting” has meant tweaking the model to allow for same-day and weekend appointments, plus opening walk-in clinics in addition to urgent-care facilities.

The private model has different drivers when it comes to access, Vaccaro says: “I have to make you happy, because if I don’t make you happy, you go elsewhere. And then I go away tomorrow. But if you’re at an institution, that institution is not going away tomorrow.”

This is not to dump on the institutions, which perform plenty of services that private practices can’t and serve as cornerstones of the regional economy. (Also, please note where all that research and innovation is coming from.) But private practices have an edge of their own in the medical ecosystem: One 2018 Merritt Hawkins survey showed independent physicians seeing 12 percent more patients on average than employed physicians.

Herein lies yet another problem contributing to long waits: Thanks to the many economic pressures on medicine (including the havoc COVID wreaked), the number of private practices in the U.S. is shrinking. Doctors employed by a hospital or corporate entity shot up from 62 percent to 70 percent between 2019 and 2021. “Is the End of Private Practice Nigh?” Forbes pondered a couple years back.

One would hope not — aside from that being a bummer, more options are obviously better for patients. As Lieberman posits to me: “Does a shortage mean that every practice is full? Or is it just that certain popular practices are full?” With this in mind, I recently checked how soon I could get in for a physical with my own PCP: four months. Then I called, somewhat randomly, the Ala Stanford Center for Health Equity in North Philly — semi-expecting a longer wait, since it’s known for taking patients whether they pay or not, which you would think might make it hard to get an appointment. They could fit me in within the month, the scheduler said. Huh.

There’s good news to be found elsewhere, too — including in the Merritt Hawkins survey that revealed the troubling trend of longer appointment waits. There were two exceptions. One was orthopedic surgery, which held steady at a mere 10 days. The other? Dermatology. In 2017, the average wait for a derm appointment was 78 days. In 2022, it was nine days.

Nine!

This tracks, actually, with my last dermatologist appointment, back in January. I’d gotten in within a week and a half. At the time, I thought it was sheer luck. Now I see what it actually was: a series of small fixes (and maybe also some luck). In the past handful of years, Jefferson reports having boosted its number of telehealth follow-ups, which opened up more in-person appointments. It has expanded hours and streamlined waitlist and scheduling processes, including offering 10-day open-access slots, similar to Lieberman’s model.

The prospect of thinking about our access problem this way — fix by fix — is equal parts exhausting and reassuring. Exhausting because of those thousands and thousands of problems, plus the Sisyphean demand. Reassuring because it’s better than throwing up our hands, and because, as we’ve seen, sometimes things actually do work, and people get the care they need. Just ask Elaine Gallagher. Over her 30 years at CHOP, she says, “I can see that we’ve made a difference. We’ve increased the number of patients we’re seeing.” That’s not everyone’s lived experience, she knows. Also: How much care could ever be enough in this world? And yet, she says, “We are making some dents.”

Published as “The Waiting Game” in the May 2024 issue of Philadelphia magazine.

The City of Philadelphia Mysteriously Disappears From Facebook and Instagram

Thumbs down on Philadelphia disappearing from Facebook and Instagram (image via Getty)

Check phillymag.com each morning Monday through Thursday for the latest edition of Philly Today. And if you have a news tip for our hardworking Philly Mag reporters, please direct it here. You can also use that form to send us reader mail. We love reader mail!

The City of Philadelphia Mysteriously Disappears From Facebook and Instagram

UPDATE 4/22 2:44pm: The problem has been resolved. Here’s what Meta spokesperson Andy Stone had to say: “We fixed a bug that temporarily prevented people from being able to select Philadelphia as their current location. Or as my Philly advisers suggested I say: youse don’t have to worry, this jawn is now fixed.”

ORIGINAL:

No one is exactly sure when it happened. Some say Wednesday. Some say Thursday. But this much is certain: At some point in the last week, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, disappeared from Facebook. Philadelphia social media was all atwitter over this mystery for much of the weekend.

“Hey, Facebook, what’s going on with ‘Philadelphia, PA’?” wrote one Facebook user last Thursday. “Why was it removed as my current city? Why is it not available as a city to add back to my profile? And why does it seem none of my friends who currently live in Philly have it on their profile either? Why the hate for Philly?”

Indeed, if you look at the profile of anybody who lives in Philadelphia, you will see that Facebook no longer has a place listed for their current city. And if you had Philadelphia set as your original hometown, same deal. Should you want to try to fix this by adding Philadelphia back as your current city or hometown, no dice. The option of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, simply does not exist.

I ran a check on other major cities. New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Detroit. I could go on. All of them exist just fine. And from what I can tell, no other places in Pennsylvania have been affected in this way. Pittsburgh is there. My birthplace of Norristown is there. Lancaster? Yes. State College? Yes. Even New Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, a tiny former coal-mining town of 1,000 people way up yonder in Schuylkill County, still exists, as far as Facebook is concerned.

The problem is affecting Instagram as well, Instagram being part of the Facebook parent company, of course. Philadelphia businesses that previously had Philadelphia included in the addresses on their Instagram profiles now only show street addresses followed by a comma followed by … nothing. Where did the “Philadelphia” go?

So is this just some kind of weird technical glitch? Is Mark Zuckerberg not a big fan of Philadelphia? Or maybe some jilted lover who works for Facebook decided to wipe their ex’s city from the universe? The cause remains unclear. Facebook has yet to reply to my request for an explanation.

Why Would Ornithologists Want to Rename Birds?

Well, ornithologists have been naming birds after scientists for centuries. And many of those scientists were from right here in Philadelphia, a fact that’s not surprising given that Philadelphia is considered the birthplace of American ornithology. But here’s one of the main issues: Some of those ornithologists owned slaves. And so now the American Ornithological Society isn’t just renaming birds that were named after slaveowners, racists or misogynists. They’re gutting the whole program and just renaming any bird that was named after a person. Peter Crimmins has more on this story over at WHYY.

By the Numbers

$9,000: According to this scathing report in the Inquirer about how the office of Sheriff Rochelle Bilal spends money, that’s what the office paid for a silly mascot that rode along with Bilal during the 2023 Thanksgiving Day Parade.

15,000: Square footage of a Bucks County estate that’s about to go up for auction next week. The estate includes not just a hot tub, heated garages, a gazebo, 5,000 square feet of pricey Brazilian cherrywood, an outdoor kitchen, and a gorgeous river view but also an underground bunker! How exciting.

1: Days in the seven-day-forecast that temps are expected to hit 80. The rest is a mix of mid-60s to mid-70s. Kind of like the crowd at Hymie’s on a Saturday morning.

Just Who Is John Fetterman?

That’s what Philly Mag contributor (and former editor-in-chief) Tom McGrath asks in this deep dive into the unorthodox guy that Pennsylvania voters turned into a United States senator.

Local Talent

If you’ve been a longtime fan of Philadelphia sports broadcaster Glen Macnow, you’ll be sad to know that he’s leaving the airwaves soon. Macnow, who’s been at it for more than 30 years, says he’s retiring in July.

And From the Could-Be-Worse Sports Desk …

Playoff time! It was the Sixers vs. the Knicks on Saturday in Madison Square Garden, and there was a powerful Philly connection: The Knicks under coach Tom Thibodeau started three of their four current players who played together on Villanova’s 2016 NCAA Championship team: Josh Hart, Donte DiVincenzo and Jalen Brunson. (The fourth is reserve Ryan Arcidiacono.) On our lineup: Kyle Lowry, Tyrese Maxey, Kelly Oubre Jr., Tobias Harris and Joel Embiid, the last of whom scored the first nine Sixers points of the game. It was part of a strong first quarter that saw us up 34-25 at the close.

Things got a little uglier in the second, as the Knicks came back to tie it at 36 in the early going. Lowry picked up his third foul halfway through the second, and the Knicks were thumping the boards. Nico Batum hit a couple of threes, but New York crept ahead as Brunson started hitting. And then Joel hurt himself on a slam dunk and lay on the court with his eyes wide, while Philly fans’ hearts stopped.

OMG JOEL EMBIID JUST BAPTIZED HIM 😳 pic.twitter.com/WJDfw7GfJ2

— Swizzy (@swxizzy) April 20, 2024

Paul Reed came in for him to finish the half, which ended with the Knicks up 58-46 after a 9-0 run. And Joel was back on the floor for the third, thank God. The Sixers had an 8-0 run to get back within five, then three … back in front to start the fourth, 82-79. It stayed neck-and-neck, but Hart kept hitting threes, and it ended up a New York win, 111-104. Game 2 is tonight, again in New York, tip-off at 7:30 p.m. In other news, as expected, Tyrese is one of the three finalists for the NBA awards’ Most Improved Player.

The 2023-24 #KiaMIP Finalists.#NBAAwards https://t.co/FRZqX6Ha0K pic.twitter.com/T011JdKOiB

— NBA (@NBA) April 21, 2024

How’d the Phillies Do?

Well, on Friday, in the opening game of a series with the White Sox, Alec Bohm obligingly spotted starter Spencer Turnbull a 3-0 lead by homering after Trea Turner singled and Bryce Harper walked. In the third — stop me if you’ve heard this — Turner doubled, Harper walked, and Bohm homered again.

https://twitter.com/Dr_Juice1/status/1781466374864323069

Whit Merrifield came through with a solo homer in the bottom of the fourth, and that was the end of Sox starter Garrett Crochet; Chris Flexen came in. Turnbull, meanwhile, just kept grinding away; he didn’t allow a hit through one out in the seventh, when Gavin Sheets notched a single. Matt Strahm came in to pitch the eighth and gave up a single and a walk but nothing more. It was Orion Kerkering in the ninth, for three outs in a row and the Phils’ fourth straight win.